Maybe you’re in the post-graduation slump. You’ve got loans to pay, no job, fewer friends than before, and the requisite depression. Or you’re humming along in school, always a little too tired and a little scared about what’s coming next. If you went to school ages ago, you’re counting your lucky stars. If you never went or dropped out, you just might be too. Between money and sanity, a university education could be one of the most costly investments you’ll ever make.

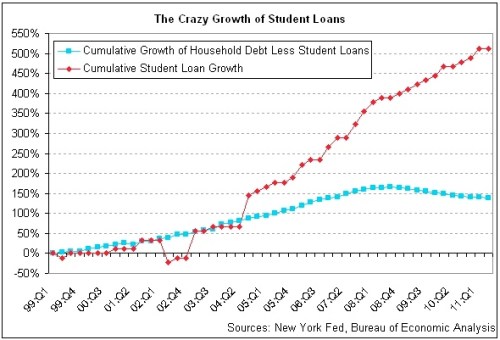

If you’ve ever felt like something’s wrong with American colleges, you’re not alone. The statistics are flooding in and they’re on your side. According to Benjamin Ginsberg, a political science professor at Johns Hopkins, tuition rates at public universities have tripled since 1980 while tuition at private schools has doubled. That’s three times the rate of inflation since 1982. The only other good or service that’s seen that kind of price hike is cigarettes. To compensate for the growth in tuition costs, students are taking out loans are alarming rates.

Professors Andrew Hacker and Claudia Dreifus believe that what’s coming next for student debtors could be disastrous.

“The next subprime crisis will come from defaults on student debts, starting with for-profit colleges and rising to the Ivy League. Still, there’s a difference. With mortgage defaults, banks seize and resell the home. But if a degree can’t be sold, that doesn’t deter the banks. They essentially wrote the student loan law, in which the fine-print says they aren’t “dischargable.” So even if you file for bankruptcy, the payments continue due. Hence these stern word from Barmak Nassirian of the American Association of College Registrars and Admissions Officers. “You will be hounded for life,” he warns. “They will garnish your wages. They will intercept your tax refunds. You become ineligible for federal employment.” He adds that any professional license can be revoked and Social Security checks docked when you retire. We can’t think of any other statute with such sadistic provisions.”

Um, terrifying. The obvious questions–where is all this money going?–isn’t an easy one to answer. Ginsberg points to the glut of administrators on campuses as a major tuition-sucker. While the number of professors employed has increased around 50% over the past 40 years to keep up with growing enrollment (the student to faculty ratio has remained nearly constant at 15-16:1), the number of administrators has grown 128%. While universities justify the number of administrators employed by citing new demands in enrollment and technology, pressure to keep up with external mandates, and unwillingness from professors to perform administrative tasks, Ginsberg paints a different picture. He mentions case after case of administrators abusing their power and reveals the high cost of president and deans. Ginsberg believes that professors have no desire to take part in administration, not because they see themselves above it, but because any power they used to have has been stripped and redistributed among an “army of functionaries” who view the means (management) as the end.

The means/ends dilemma isn’t one that’s confined to bureaucracy and meetings. Students are often unsure about why, exactly, they’re at college. A 2009 survey of Penn State student (totally not scientific, I know, but bear with me here) showed that nearly half of freshman said they were there “to prepare for a vocation [or] learn what I have to know in order to enter a particular career.” Next came “to pursue scholarly activities for intellectual development,” followed by “to discover and develop my own talents,” and finally “to become more mature, learn how to take on responsibility and become an adult.”

Throw tuition into the mix and that’s enough to make anyone’s head spin, let alone an 18-year-old who, as Hacker and Dreifus point out, are not exactly experts at handling money. Our model for financing education requires one of three things: students (ahem, parents) must be able to pay up front, students must win scholarships, or students can take out loans. While scholarships are available, universities rely on accepting a class of students who will pay at least 50% of their tuition costs to come out even. If you take a second to harken back to that ugly ugly graph (or your own bank account), it should come as no surprise to you that most students take out loans.

Universities justify such high numbers by citing studies that show college graduates average $1 million more in lifetime earnings compared to their high-school-diploma-fied counterparts. The $27,650 that the average American student takes on in debt is nothing compared to $1 million! One of the major issues, though, is that payment on student loans begins 6 months after graduation. While expanding one’s mind at college is a noble pursuit, it often comes at the noble price of having a family who can alleviate the financial burden of loans. Instead, most students are under pressure to study something that directly translates into a high-earning job.

Having college graduates with workforce-ready degrees doesn’t sound like a bad thing for our clearly depressed economy, but what might work now isn’t going to cut it in the long run. As we experience changes in technology and as outsourcing becomes even more routine, those jobs that once opened a direct pipeline to the bougie life will no longer be so profitable. I know I’m biased, but I believe an undergraduate education in the liberal arts creates students who are comfortable with change and excel at creativity–both invaluable skills in the modern labor market.

The problem with universities is that there isn’t just one. With every solution comes fifteen unintended consequences. It’s not a matter of just changing educational priorities, balancing administrative and faculty employment, or tackling the student loan crisis, it’s figuring out how to juggle all three.

Comments

Try about $4000 a semester when both of your parents are unemployed. Yikes.

Since I started school, at SFSU, my tuition has pretty much doubled. This past summer they voted to increase the tuition again, that same day I changed my major to something I don’t really want to do, but it’ll enable to graduate a year earlier than I would’ve.

”We are making higher education more of a private good than a public good.” – Linda Katehi, Chancellor of UC Davis.

And what’s really sad about is that as colleges become less and less accessible to lower-income students, college degrees become more and more essential in the workplace. Especially in a bad economy where employers can afford to be as picky as they want, because there are so many people applying – you have a lot of people requiring certain levels of experience and/or education that are not really necessary for that job, just because they can. If this trend continues, the gap between the rich and poor in this country, which is already so wide in this country, will just get wider. But what can colleges do? When there’s so little money to go around, they have to charge more.

I really wish there was a fighting chance for universal college tuition in this country. Alas, when even universal health care barely squeaks by, that will probably never happen.

This is so true and sad. These kind of issues that are making think more and more about socialism and how I want to move to Sweden.

the quote, baffles me. they’re starting to disable the middle class from getting an education. then only the upper class will be able to get high paying jobs and remain in the upper class

This year I chose to turn down my Ivy League dream school that wanted me to take out nearly 40k/year in loans (WHYYY, Columbia? WHHHY!!?). Instead I’m going to attend a state school where I’ve received a scholarship that is nearly a full ride. These kinds of scholarships are limited though, over 4,800 students, who I’m sure could all have really, really used it, applied for the scholarship I received, and only 100 students got it. There is some funding out there for school and it’s really important that students look for it, but there just isn’t enough.

The cost of tuition in this country is ludicrous, and I find it disgusting that private lenders are receive the same guarantees as the federal government on student loans. Even a student who becomes disabled and is not able to work is still subject to these insane repayment terms.

I’d love to see Autostraddle run some articles about options for paying for school. There’s nothing wrong with attending community college for two years first (which is what I did while working full time, and I currently have an associate’s degree with zero debt and I was accepted at some really great four year schools), and it’s a great way to save a tremendous amount of money. I also had some really amazing teachers at community college, and it was a wonderful experience.

Additionally, many states have scholarship programs to their state schools for students who earn a certain GPA or SAT score, and it’s always great to know what those benchmarks are so that you can try to meet and exceed them. Some states, like Oregon, have scholarship websites specifically for students in their states where there is a simplified application you can use, like this: http://www.getcollegefunds.org/ (Oregon only, but many other states have similar resources.)

Check your school! Many schools have lots of scholarship options (a good way to find them is on Cappex.com, I’m not affiliated with them in any way but I seriously love their site), and you can make a spreadsheet of when the scholarship deadlines are and of their requirements.

Of course there are also scholarships especially for LGBTQ students which are totally worth applying for, but this may not be an option for students who aren’t out to their families.

An important thing is: be aware of your actual earning prospects. Many schools will be less than honest with you about this, and it’s important to do your own research. If you plan to be a social worker, that’s awesome (seriously!), but you’re going to get paid crap and you will probably be happier for the rest of your life if you go to school in-state and aren’t living off of cat food when you’re 80 and still making a $500 payment every month.

“There’s nothing wrong with attending community college for two years first (which is what I did while working full time, and I currently have an associate’s degree with zero debt and I was accepted at some really great four year schools), and it’s a great way to save a tremendous amount of money. I also had some really amazing teachers at community college, and it was a wonderful experience.”

I do wish people talked about this more, but it is worth noting that this isn’t an option for everyone. Mine is the sort of program where it’s specialized and there really is a huge different between a place with a so-so program and a great one, since how schools approach it varies so much. I think going to community college would have been a mistake for me. But I do think that people for whom it is an option should explore it. I know from my older sister’s experience that it’s also a good idea if your high school grades were not that great but you know you could get into better schools if you studied harder. After a year in community college my sister was able to get into Michigan State, which would never have accepted her based on her high school transcript alone.

*huge difference. Grrr typos!

That’s true, there are some programs I’m sure that do require very specialized things, but for most students 1-2 years getting their gen ed requirements at a CC would save them lots and lots of money.

I never had any other option, because my father was homeless and didn’t file taxes so I had no ability to get financial aid till I turned 24 (hence me entering my Junior year a month before I turn 25), and my options were private students loans which I couldn’t get due to medical debt (I have no cosigner) or paying out of pocket, which is what I ended up doing.

It was really a better option than I expected though, so outside of programs where you REALLY REALLY need to take your core classes/gen ed requirements somewhere specific, I feel that students shouldn’t be so quick to dismiss community college.

The other main reason I can think of to not do community college is if your parents home is a dangerous situation and you need to move out, since they don’t tend to cover living expenses in their financial aid award. However, it can still make sense to just find some roommates and work part-time or full-time for that year or two while attending community college, since you might still save 20-80 thousand dollars or so.

yeah this actually happened to an ex-boyfriend of mine — he’d been shuffled around in foster care and was eventually adopted by his great aunt and great uncle, who then took him out of state w/o the court’s permission, apparently, which classified him as “a ward of the state,” which, somehow, coupled with the fact that he’d been working full-time while going to school for years and therefore pulled in about $15k a year, he was somehow not qualified for student loans or financial aid, according to the government. he did the two years of community college thing first before transferring to eastern michigan. regardless, he’s still in debt, i imagine.

DUDE I feel you on the not-being-able-to-go-to-Ivies-because-they-suck-balls-at-financial aid thing. However, I am glad that I decided to go to a decent school that gave me a full scholarship because when I graduate I won’t have loans out the wazoo. In fact, I realize now that I’m happier at BU than I would have been at an Ivy–so if any of yinz get a scholarship to a school that isn’t your dream school, accept it!

That’s good to know that BU is generous, I’m considering them for grad school. Do you know if they’re nice to grad students, too, like giving out lots of assistantships or offering stipends?

I could not tell you anything about their grad school in terms of financial assistance; in fact I couldn’t even tell you much about their undergrad financial assistance because I have the “write 600 words about this prompt and you win a full scholarship” scholarship. So in terms of merit scholarships, they’re really good. I also know that many of my friends selected BU as their school partially because of the scholarships/financial aid they received. If you want to message me, I can totally rant on about how much I want to make love to BU–but sorry, I am only a sophomore and don’t know a ton about assistantships or stipends! :/

Actually, a lot of Ivy League schools give the very best financial aid, and almost all of them offer packages without any loans. In fact, every Ivy I got into was extremely generous and gave me a financial aid package well in excess of even what I was hoping for. Although private universities have the highest tuition, they also sometimes have the highest endowments which allow for such impressive aid.

welll yes that’s the case sometimes, but I think I just applied to the asshole Ivies (and some of them, for example Princeton, put me on the waitlist so that there was virtually no chance of me getting financial aid by the time I got off.) So you must have just been cool enough to not be waitlisted, or you just applied to the right schools haha. Where did you end up going?

Some of the Ivies only offer loan-replacement grants to incoming freshmen. :(

Yes. But there is a portion of tuition called “self-help” (at least for the Ivy I went to) which is just code for “you’re fucked” since it’s not covered by FAFSA, Pell, or the school’s aid. Even with the best financial aid packages, you’re still looking at loans.

At times like this I’m genuinely happy to be living in France.

I’m starting law school soon and will pay 177€ (256$) a year (refundable for low-income students).

I wish Americans weren’t so afraid of the “socialism” word, especially if we could create an economically viable way of giving everyone access to education and healthcare.

I agree with this completely. Socialism is appealing to me more and more with the things that should be public goods aren’t provided.

I love Scotland. No tuition fees for Scottish residents. I wish everywhere was the same.

The other problem is that these days, in some fields, a bachelor’s degree isn’t often enough anymore. It’s better than nothing, but often you need graduate school to be truly competitive. I’m going into so much debt over a degree that is really just a stepping-stone to the degree I really need. At least it’s also a way to stave off paying my undergrad loans, too (since the ones I have don’t start requiring payment back until I’m no longer enrolled full-time in school) and I’m the academic sort of type who always planned to get an advanced degree so it’s not like I feel forced into it. But I know I’m not everyone.

I am the same way, I need this b.a and I am taking loans but the big guns will come later for my mfa ugh! Good luck!

Plus I find this to be really disturbing because price of education is getting even more tied into class which is influenced by so many factors. I am lucky that I am privileged enough for my first degree paid for and only taking loans for my grad degree. Change the world homogays and allies! We are going to need it desperately.

I think a lot of people would be better off just getting three years of work experience and working their way up, rather than incurring the debt of getting a master’s degree that would get them the higher salary. I had thought about going back to school, but after a few years of paying my dues, I am earning close to what I think I’d be hoping for after grad school. I guess it depends on the field, but I think sometimes people just go back to school because they aren’t sure what their next step is — I know uncertainly about my future played a big part in my plans to return to school.

In this economy, do they said it is or is not a good idea to go back to school if you have trouble finding a job? Hmm.

You’re probably right; unfortunately, I’m in one of those areas where an advanced degree isn’t just a good idea, it’s mandatory if you want any kind of regular job in the field. A bachelor’s degree in music composition is basically useless.

“A bachelor’s degree in music composition is basically useless.”

That’s exactly why I have to give up studying music at uni. Sure, music is extremely important to me, but I can’t really afford (pun!) to spend so much money on a course that isn’t going to enable me to earn enough money after uni.

Also, the idea that if you can’t get a job you should go back to school, is just ridic.

Well, it’s always been my plan to get a doctorate and teach music in college, it’s not just something I’m defaulting on because I can’t get a job as a freelance composer or whatever.

Anyway, why is it ridic to you?

Oh, I wasn’t implying that it was a default! Sorry if I unintentionally did so.

I think, just the cost of education, really. This is purely personal opinion as I know a lot of people who are struggling to find jobs and have been told that they’ll have to go back to school to get more qualifications. In their situations, it’s just not possible, both financially and because of childcare restrictions. I feel like there should be another way to help these people who have families to support etc and can’t manage going back to school.

But of course, I’m talking about older people, as opposed to those just graduating :)

Amen! How the Hell am I supposed become a doctor and help people/animals when I even go to school to begin with?

P.s. That picture of Justin beer is making me really mad

I graduated with $70,000 in student loan debt! Learn from my mistakes, young whippersnappers – don’t go to private colleges if your parents/the school isn’t footing the bill! Not even just for one year! Not even if when you’re starting school, your country isn’t in a recession/depression and interest rates sound reasonable (ooh, 2005/2006, I vaguely remember you)! Whee!

Unfortunately, depending on the academic program, some of us have no choice but to attend expensive private colleges. I wish I could have gone to a cheaper place, but my school was the only really good one where I was admitted.

(and all the places I got in were private, though some of the others gave me much bigger scholarships)

I’m 60k in the hole after 4 years at Sarah Lawrence and, despite it not being everything I hoped and dreamed of, I don’t regret it for a second. The education and experiences I gained there more than outweigh the amount of money being siphoned out of my bank account every month.

Granted, I’m semi-gainfully employed (despite having a ‘useless’ liberal arts degree) and frugal. If I didn’t have a job I would probably be singing a different tune. I’m *definitely* happier in this situation than if I had spent the last few years at my local state school. I was REALLY fucking scared about finances while I was still in school, but things ended up working out.

I absolutely think that something needs to be done about the cost of education in the US, but I also think that the money is worth it if it will take you the places you want to go.

You have to be at a certain level to make that decision, though. People who have no money can’t spend money they don’t have to attend the very best place.

When I chose my school, I was in the position where I could afford to pick the very best one for me and my academic interests. While I’m happy I chose the place, I’m now scrambling to finish my degree – and knowing I won’t have the same freedom to choose my grad school, that I’ll be forced to go wherever I get the best financial aid package.

I’m lucky enough that the $56,000 per year bill can be covered by my family, but I periodically have nightmares about how much I’m bankrupting my family and what would happen if my mom was fired from her job, or became disabled, or various terrible things through which I could become a horrible horrible money sucker. College is so damn stressful in every way possible.

okay a slight lie, 52,000, but STILL. So freaking massive. I can’t even express how fortunate I feel every minute I’m here.

Ahhhhaa . . . I see numbers like those and I just kind of hyperventilate in confusion. Like, I *know* that half the kids at the college I went to had their parents paying the (expensive tiny private college) tuition but I still cannot really even believe that is possible?! That there are That Many people out there who make enough money to do that?? The figure up there is probably about twice my mom’s *annual salary* around the time I started school.

Anyway, I got by on a super generous financial aid package and a bunch of loans and work-study jobs, which worked okay. But even with all that, I still had to work 60-hour weeks at two jobs in the summers and felt like I was under constant threat of not having enough money to come back in the fall. And I loved the hell out of my college experience and it was worth every penny (and the sizable loan payments I’ll be making for years), but it definitely built up a deep reservoir of class anger that’s still very much there inside me.

oh thank god for this article. i knew i wasn’t the only one with financial stress regarding tuition, but IT STILL FEELS SO SCARY. my school is pretty fucking “cheap” compared to most but i’m freaking out about where the money will coming from to pay for it plus i feel super guilty giving my parents the bill and also i feel mad about feeling guilty because WHY in this country that markets “land of opportunity” as its greatest quality should it be so FUCKING hard to get qualifications to just get a fucking regular job to fucking support yourself. ITS SO DISHEARTENING. FUCK.

THIS. I haven’t even transferred out of community college yet, but I feel so much guilt over the prospect of putting my family in debt (and we would be in serious debt, even for a state school). No matter how many times my parents tell me not to feel guilty, I can’t get over it. Neither of my parents went to college. Both of them have good jobs that don’t require a degree and we live comfortably, have nice things, and go on nice vacations…I am so tempted to just follow in their footsteps and just get my AA and be done, but they really want to see one of their kids graduate college. I just want to be able to get a job and support myself, and not have my parents worry about me and money all of the time. FUCK.

I’m pretty fortunate because my father is/has been paying a portion of my loans and I’m paying the rest off (I left Penn State with about $15,600 in student loans). What sucks though, is that I have a bachelor’s in Journalism and I don’t do anything remotely close to that AND I’m getting paid more at my shitty job than if I were a journalist…but that’s a complaint for another time.

Yes, I just got my master’s degree this spring and I’m actually in a job I love and that pays well that I got just a couple of months before graduating — but it isn’t at all related to my degree and definitely wasn’t an asset in getting me the job. It’ll be good to go back to, I guess? (It’s a kind of terrible time to be getting into my degreed field anyhow.) But meanwhile I’m just kind of sitting on this thing that I sunk a ton of time and energy and money into getting, so that feels weird sometimes.

While I applied to some good private colleges, there was no way I was going to accept partial scholarships yet still have to take out 20K+ per year in loans. Especially when that same amount would cover all 4 years at my eventual public in-state university. It feels nice that the entirety of my student loans stem from housing and a once-in-a-lifetime study abroad experience rather than overpriced college tuition. And I’ve been able to find a crappy post-grad job that’s at least relevant to my major.

Although over-priced tuition and student loan debt will be pretty much inevitable if I get accepted to and choose to attend the law school of my choice.

You didn’t mention that a significant number of that faculty is adjuncts/lecturers/grad student TAs, which get paid next to nothing. I think the average salary for adjuncts is $3000/class, which means teaching 10 or more a year just for survival. So really, tuition (and state funds) goes less and less to faculty and classes (you know, the reason you’re THERE), and entirely into administration and administrative costs.

Which is BS.

Cut that number in half. Then, factor in caps: most places only allow adjuncts 2 or 3 classes/semester. Just to do what you’re suggesting, they have to teach at multiple schools, often without benefits, etc. Then, bring it back around to how much it costs to pay for a Masters or PhD.

totally. i also didn’t mention how much money goes toward student life. colleges spend so much money making themselves attractive to freshman because we have this ideal that college is the be-all-end-all of life. which sets up an unfortunate expectation that graduation will be awful. and then it is. maybe something needs to change there too so that it stops being a self-fulfilling prophecy. (p.s. i don’t mean stop spending money on student clubs etc.! those are obvs important. more the ridiculous kind of stuff like free music downloads.)

i attend a private college (Rochester Institute of Technology) in New York, and feel lucky that i can commute. even though i have no other choice this year. last year, we didnt take out enough money for loans so i ended up paying a few thousand out-of-pocket. i may have lost money, but in the long run, i’ll be saving. the interest rates on loans are ridiculous, so by paying out of pocket now, i saved that money, plus the interest.

by commuting, i’ll be saving a lot as well. room and board is around 9,000 a year. thats money that you take out loans for. so add the interest to that, and i save so much.

just something for other poor college students to think about

god i’m glad i live in the UK, i dropped out of school at 16 but managed to get on a nursing course and then degree which the national health service paid for and now i’m doing medicine which they’re paying for as well. It’s so important for the government to invest in their young people. I have ppl in my class who have come over from the US and Canada becuase even with international fees its still cheaper to study here, it’s crazy!

I just graduated from a NY state school with about $26,000 of debt, and that is with me getting the maximum amount of state and federal grants due to my family’s income. I feel lucky that it’s not more, especially because right now I’m fighting tooth and nail just to get a job at a fucking Target, but it’s still waaaaayyyyy more than I can possibly handle right now.

And SUNY (the NY public school system) keeps trying to get a bill passed that would allow for differential tuition at state schools, allowing each school to set their own tuition, even by program (so getting a B.A. may cost a different amount from a B.S. or whatever). And this would also make the big schools, Buffalo, Albany, Stony Brook, and Binghamton, more expensive than the smaller schools, and more difficult for low income students to attend than they already are. Luckily it hasn’t passed yet, but they keep pushing hard for it.

Add grad school onto college and you’re really screwed. Plenty of colleges charge upwards of $40k a year for tuition, then add upwards for $40k a year for grad school on top of that… so if you have, say, four years of undergrad and three years of grad school…

That’s $280k in tuition alone, not counting living expenses while you’re in school.

I haven’t met anyone with quite that much debt, but I absolutely do know grad students who are almost $200k in the hole to Fannie and Feddie.

It’s just wrong.

1.) This is so accurate and applicable to my life right now: “Maybe you’re in the post-graduation slump. You’ve got loans to pay, no job, fewer friends than before, and the requisite depression.” Except I do have a job, but I hate it and it’s in a factory, so that’s something.

2.) We’re going through all this shit with my little sister right now. It’s her senior year of high school and mom wants her to go to community college, but she wants to be a photographer, and it’s not like community colleges tend to be excellent art schools (not our local one, anyway), so she wants to go to my alma mater, which is an excellent school and surprisingly cheap. But, it was cheap for me because I got a bitching scholarship that paid half my tuition and no one seems to think my sister will get that scholarship because she doesn’t get the grades I did. Anyway, it’s fucking awful and I worry about her being miserable and I worry about her getting her feelings hurt because the conversation of “can she even get a scholarship?” is a necessary but possibly painful one.

3.) Fuck capitalism. Seriously. Fuck it. It stifles creativity and ruins lives and every 12 hour factory shift I work, I become more and more of a socialist.

“but she wants to be a photographer, and it’s not like community colleges tend to be excellent art schools (not our local one, anyway)”

Yeah, that’s the bind I was in, as a musician. Community college is a good money-saver if you don’t know what you want to study and/or you’re in a program with lots of gen-eds you need to get out of the way. With arts programs, though, you usually know what you’re majoring in coming in (since you have to audition specifically for that program) and you’re taking classes in that major from the get-go. The stuff you do at community college probably won’t help much.

EXACTLY. Even the argument, which my mom is fond of, that she can “just get her pre-reqs out of the way at community college” is ridiculous. I majored in creative writing and was working on my major from the get-go.

I guess I’m a little bit confused about this. Do you not have to take science classes and basic math and all of that for these arts degrees?

I didn’t have to take any math and science classes for a Bachelor of Music degree, but I have had to take English, poli sci and history classes. But yeah, we don’t have to take the gen-eds that people at Johns Hopkins’s arts & sciences and engineering schools do. The music school has its own freshman humanities seminar, and then the rest of the humanities requirements are basically electives, though we have to do a certain number in certain general areas (literature, history/philosophy, “global perspectives,” etc). And we have to take at least a year of foreign language or place out of it.

Really, it depends a lot on whether you’re going to an independent conservatory/art school (which tend to require less non-music classes – Juilliard told me when I visited that they only have one humanities class) vs. a music program within a larger university (where you tend to have the same gen-ed requirements as any other major). My school is inbetween those – a conservatory that is a division of a larger university but is somewhat independent and has different requirements. It can also depend a lot on what degree you’re getting – a Bachelor of Music/Bachelor of Fine Arts tends to be more specialized than a Bachelor of Arts.

Whatever your requirements are, though, music majors usually jump straight into music theory, music history, etc. in your first year, along with your major lessons, and from what I’ve heard it’s similar for the other fine and performing arts. And those curricula can vary a lot by school, so even if you go to a community college where you take a lot of those types of classes, it doesn’t necessarily transfer to a music school that might teach it in a different order. (I’ve known some friends who did community college before coming to my school and they are routinely frustrated at this.)

“which tend to require less non-music classes” should be “which tend to require less non-arts classes”

I got lucky, I came out of undergrad with only about $10k in student loans. Then came grad school and now I have over $100k in student loans and monthly payments of close $800 dollars. I’m constantly stressed about paying back the student loans and knowing that I’ll be paying them back for the next 25 or so years.

Usually when I meet people who don’t understand the concept of needing money to make money, I assume they’ve never had to pay their way through college. College taught me that upward mobility is kind of a joke.

I have this plan which involves living with my parents until I graduate, going to a very cheap school, and paying for everything in whatever cash I earn from working 25 hours a week… and also never going out because I am so so broke.

If it pans out, I’ll have no student debt and will have sacrificed most of my twenties to achieve that. On top of which, I’ll have no credit to do something like buy a house. So.

Obviously I am more than bitter over how things are set up, and I’m lucky enough to have things like access to work and parents who will/can put me up.

as much as it sucks for us all im glad to hear other people talking about money and life in college for my 3 year school im in about $45,000 plus about $15,000ish in gas to get to school since i drive every day about 130 miles round trip every day and am having trouble finding a job since i lost mine as a privet chef and nanny when the family i was working for moved. every day im thankfull i font have to pay back my loans till im out of school but dread how im going to pay for the gas to get there having missed days of class because i couldnt get to school is sucking and so stressful thanks for all the words of advice and the storys to remind me im not alone :)

I really wish I could have read this article 3 years ago before I enrolled in a masters program at a for-profit university and seen my modest $20,000 student debt (after my bachelors) jump up to $60,000 with 2 more years left of my program :(

Higher education is its own little commodity where the normal rules of inflation and, well, reason don’t apply. Surely the education bubble will bust, right?! Nah, college degrees are the new high school diplomas. Everyone needs to have them and will pay whatever it takes. There is something to be said for the cost investment — people with college degrees earn more over their lifetimes than those without.

But honestly, if it’s all the same to you, get a bunch of general bullshit credits out of the way at community college and then transfer. All anyone will ever know is you got your bachelor’s from X University.

The big drain is also living on campus. I commuted most of college. I may have missed out on some of the experience and did go away for a year to get it, but living with your parents can save you a bundle.

I went to Bowdoin College, which cost somewhere in the neighborhood of $50,000 per year. I did manage to get some partial scholarships (all needs-based; Bowdoin doesn’t have any merit-based aid), and so I’ve graduated with [only!] $28,000 in debt. I have a crappy job teaching English in China, which is semi-related to my major, but at least it allows me to pay my loans. I think a lot about how it would have been much, much better to go to the state university I got in to, but I truly feel that the quality of the education I got was better, and as much as it sucks to say, the Bowdoin name-brand on my resume has helped.(Mind, I’m not say all state universities are lower quality than private colleges — just the one I applied to). My sister’s situation also helps me keep my debt in perspective. She managed to get her BS will very minimal debt, but then she went to vet school — now she’s $200,000 in debt. I may owe the equivalent of a nice new car, but her student debt is a frigging house mortgage. If she ever loses her job, she’s screwed.

I’m kind of going a different route – the Navy ROTC scholarship. I got a scholarship for an awesome school 3 years ago, so I’m a senior now. I know most people are kind of leery of the military, because of dadt and ya know…war, but for me, and a lot of people I know, it’s a great route to go. You incur 3 years of active duty in a field that you want, like mechanical engineering or diplomacy or translating or what have you, and you have no debt, and you have a job out of college. so that’s a win win win win in my book. but whatever floats your boat.

This blows my fucking mind, all of the numbers you guyz are reporting. I’m a Canadian student: I got entrance scholarships from high school that paid for my first semester off the bat, and I continued to receive small scholarships. Granted, Mommy and Daddy did help me, but when tuition is $4000 a year, it’s not that big of a stretch, and with summer jobs I’ve always managed to pay the rest of my fees. Now I’m heading to a grad school who’s paying tuition for both years of my program. How much is that awesome scholarship worth? $10,000 – 12,000. Seriously. That’s how much my tuition costs for my Master’s.

I only had one friend take out Student Loans (because she went to an expensive school and had no family support), and we all thought she was fucking batshit crazy for doing so.

Socialism: It’s a good thing.

I’m moving to Canada. Like right now.

Holy crap people, this is outrageous. I guess you are far too busy trying to pay off your loans rather than taking to the streets to protest this insanity? No wonder there are so many American students studying here at UCT in Cape Town

Outrageous isn’t even the word. How does a country expect to get by if it won’t invest in its youth or in the education and health of its populace?

A desperate and uneducated populace, untrained in critical thinking, is easy prey for unprincipled and hate-mongering demagogues.

not to mention health care! before the new act, students lost their parents’ coverage as soon as they graduated (or turned 22? I can’t remember). one bad illness or a broken arm and you’re doubly in debt before getting your first real job.

This is the best piece I’ve read on WHY tuition is so high; basically, its the whole bring in highly-paid “professionals” to “run it like a business” idea:

http://www.washingtonmonthly.com/magazine/septemberoctober_2011/features/administrators_ate_my_tuition031641.php?page=all&print=true

students and parents should be demanding change.

…and now i am a walking example of the over-worked professor. stay up most of the night finishing writing an article, drag myself out of bed because i teach today, read first paragraph of autostraddle piece on student debt, feel intense depression and rage, fire off comment, go deal with multiple student freakout emails, come back to article, realize study i posted in comment is already included in article; feel shame.

no big deal! it is a really good article.

Wow, this scares me so much. I have wanted to go to school ever since I graduated in ’08 but I am kind of being kept as a domestic prisoner for my family. I want to have a future, to be independent, and to have a life of my own but maybe I waited to long to put my foot down!

Emma, you can do it! You can start with even one class a term at your local community college, you can do it online too. There are ways to go to school without incurring all of this debt, it’s just not always the right option for everyone, but it sounds like a good option for you.

It was exactly these considerations that caused my family and I to not consider taking out loans at all. I’m entering my junior year at a private school in Minnesota (St. Olaf College) with no debt. I received 20k in merit aid plus a 12.6k need based grant, and 2.3k in work study. I’m very thankful for my family and them being able to cover it, but if that amount of aid hadn’t been offered (it was for me at three schools, including one ivy), I would have just gone to my state school. Seeing these numbers is just mind boggling. I hope people start to strive to change the system because it’s so obvious that it isn’t working. I’m thankful everyday for how lucky I am, but damn…this is making me not want to go to grad school.

I’ve decided that if s*** truly hits the fan…I may have to do some things around Midtown that I’m not proud of. Either that or sell crack. Hopefully not though.

this article stresses me out too much to read right now. actually, this article and the letter from Direct Loans sitting on my desk stress me out too much to read right now.

The recent bill to avert the debt crisis has eliminated subsidized loans for grad students, as well as the typical six month respite from bills after graduation. This will make upward mobility even harder because students will have to find a way to pay their grad and undergrad loans while hitting the books. I am so glad that I am graduating this year, but am terrified about having to pay back loans right after graduation. Living at home isn’t an option, so I will have no money and…a Masters in History/Museum Studies. I suppose I am privileged to have a Masters at all. It’s worse out there for people who cannot afford college.

I think the high debt really makes students more submissive and conservative than they otherwise would be. It’s hard to take risks and rally around a cause when you are working 60 hour weeks or are terrified of defaulting on your loans.

Ugh, I knew the Repubs would find a way to fuck over students one way or another.

In Australia we get a pretty good deal. Even the most prestigious universities don’t have fees in the 30,000’s + range like they do in the US. Plus, we get to defer our whole tuition cost if we want to. Then we pay it back once we earn over $44,000 for our salary. Then you pay back 4% and it increases depending how much you earn. We have a loan limit of $80,000 for HECS (the govt loan) which can get you through a good university and graduate education quite easily. Average full uni degree cost is $20,000-30,000 in tuition for an undergrad degree and $20,000-40,0000

And the reason you – and other local Aussie students, and I’m guessing elsewhere for that matter – get such a good deal?

Because us international students pay for everything up front. We HAVE to; no choice. Scholarships are super limited, it’s like winning the lottery. Fees are at least 4 times what local students pay. Loans are not an option. And many students come from countries where the currency isn’t as strong – parents end up working extra or saving up for EVER or doing all sorts of things so that their child can have a good education. if it wasn’t for international students the national economy would collapse.

and what do we get for that trouble? “oh you’re all rich brats”. as if.

That’s not really fair,.and the reason for that is more history than anything else. international students used to be able to come to Australia and study for free in the 70s and possibly 80s, my friend’s Dad came from Malaysia and didn’t have to pay a cent. so now of course current students are paying for it.

sad to say but it’s true, it would be cheaper for international students particularly in south east Asia to study at home rather than cone to Australia, right?

I am really questioning my decision to attend a very expensive private liberal arts school. It was fine at the beginning when I was getting really great financial aid but then my sister graduated from college and they cut my financial aid in half. As if suddenly my sister wouldn’t be dependent on my parents anymore or need my parents help. Now they can put all that money towards paying for my eduation, right?! Um, no. The amount of money my parents have for me (which wasn’t even as much as they estimated in the first place) has not changed. The amount I have to take out in loans has.

I really don’t know what I’m going to do but I’m very thankful that my girlfriend didn’t have to take out any loans for school since her parents could afford to pay for it out of pocket. At least between the two of us the debt we have to pay off won’t be SO high. It’s still ridiculous, though.

I have absolutely no idea where all that money goes. Especially since I’ve worked in Residential Life and they get close to nothing. Which makes no sense to me since putting money into the residence halls would be one of the best ways to give the money back to the students…so to speak. And my school requires students to live on campus for two years. It’s really silly.

In Puerto Rico a friend was telling me that at her school the students held a protest/boycott of the school, which is public, for raising tuition. This was no small thang, they took over the school, there were riot squads, they held it for months and were forced to grow food in gardens, build compost toilets, and make secret passages b/c the police had cut off the campus.

Ideas ideas ideas…

Ugh. Loans, a source of much anxiety.

It’s hard to avoid though. And I HATE when people keep telling students to just apply to as many scholarships as possible and don’t stop ’cause money’s out there waiting for you, blah blah!! Well, I did do that my first year. But that was before I knew my struggling, barely-making-ends-meet parents would have to pay taxes on all that scholarship money, adding another financial strain on them for the next year. So as much as it sucks to put my future self in debt with loans, it’s the best option. You just accept the fact that, as a student from a low-income family, you’re gonna get screwed over no matter what, really.