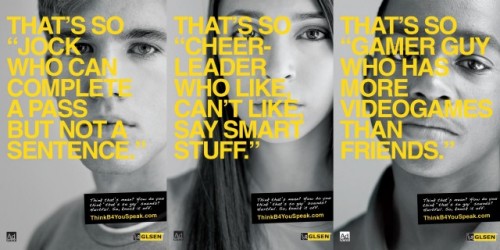

What’s in a word? Does the use of words like “fag” and “dyke” and the phrase “so gay” contribute to homophobia among young people? It’s pretty taken for granted that they do. But are slurs really such a big deal, or are there bigger issues we need to fix first before going after the language? GLSEN clearly believes the former, as they have a specific campaign, Think B4 You Speak, dedicated to ending the use of the aforementioned words and phrases. (You’ve seen their commercials featuring Hilary Duff and Wanda Sykes, haven’t you?) Whether it’s working or not, people are taking notice, both inside and outside of the LGBT community. The Special Olympics has recently started its own “Spread the Word to End the Word” campaign dedicated to ending the use of the word “retarded,” and it uses a lot of the same tactics: Internet pledges and petitions, commercials featuring celebrity endorsements (including Jane Lynch and Lauren Potter, who plays Becky on Glee), and guides for students on how to start the discussion. Clearly, language is an issue that a lot of activists across the social justice spectrum think is important.

Yet, for many teenagers, these slurs may not be as serious as they are to the adults behind these campaigns. An Associated Press/MTV survey found that a majority of American young people are not bothered by the use of offensive slurs by their peers:

Fifty-one per cent of those polled said they see slurs on Facebook or MySpace but most (57 per cent) say these are due to people trying to be funny.

Only around half that number believe people who use slurs hold hateful views.

Just a third of young people saw words like ‘fag’ and ‘slut’ as seriously offensive.

That’s quite a lot to tackle. Most people are automatically going to see this as a bad thing — that these kids are not getting the message that GLSEN and the Special Olympics are trying to send, that language matters and can hurt people. Another possibility is that there’s so much of it out there these days that kids have become desensitized to it. On the other hand, at least some of the kids telling us that they’re not affected by the language are those who it’s intended to hurt:

Of those who are gay, or have a gay friend, 36 per cent find the word ‘fag’ offensive online, whereas just 23 per cent of others did.

While there is a significant difference there, it’s still a minority of gay students and allies (though I have some issues with them lumping in allies with kids who are actually gay, and would like to know how the individual numbers differ) who are bothered by homophobic language. When so many kids are being bullied for their actual or perceived sexual orientation, but they aren’t too bothered with homophobic language — maybe these kids are telling us that GLSEN is missing the mark. Maybe language isn’t the problem.

It reminds me of this Dan Savage video where he is asked to give his opinion on the subject of anti-gay slurs. When I heard him start to say that such language-policing is wrong because he, a gay person, likes to use “fag” and “so gay,” I was all ready to disagree with him on this. But then he said this:

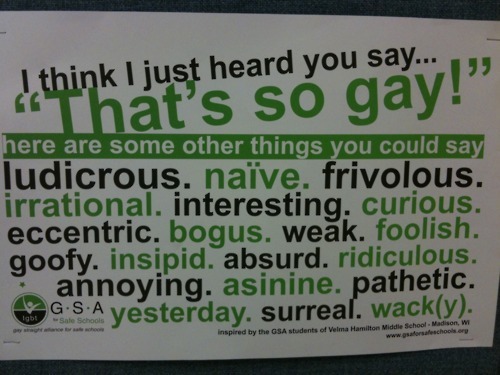

As adults we have a responsibility when kids use “That’s gay” to put it in their heads that that’s a little fucked-up…But the occasional “That’s so gay” in a high school that has a Gay-Straight Student Alliance and openly-gay kids who are not being tormented and bullied, is pretty small beans. But, a “That’s so gay” in a school where gay kids are being brutalized, it becomes another kind of brutalization.

It hit me because it reminded me of my own school days. I went to a high school that was like the first example Savage gives: Most of the kids were supportive of gay rights, and the minority was not a very vocal one. There were lots of openly-gay kids (and at least one openly-gay teacher) and even same-sex couples, who were able to be just as obnoxious in their hallway make-out sessions as the straight couples. We had a Gay-Straight Alliance, and it was respected — but it didn’t have that many members, because many gay students didn’t see why we needed one. (In fact, a large number of the members when I was there were bisexual or trans*, two groups that were less understood and accepted — the exceptions that proved the rule.) Of course, even high schools like mine were still full of immature boys who loved shock value and who enjoyed slinging around homophobic words, but in an environment where gay kids were accepted and empowered, we could just laugh in their faces.

Contrast that with my middle school experience, where hearing every single kid throw “gay “around as a synonym for “stupid” was just one more reminder that being gay wasn’t okay on top of being surrounded by fundamentalist Christian classmates, their parents, and even teachers who loudly and explicitly opposed gay equality. All things considered, I’m going to have to say that I agree with Savage on this one, that offensive language is a problem when it’s the straw that breaks the camel’s back, when it’s the cherry on top of a mountain of crap that gay kids are forced to endure. They’re like Dementors — slurs need an environment full of hate and fear to be powerful. When gay kids are happy and accepted, those words shrivel and die, and aren’t that difficult to defeat.

Another thing that Savage says that resonates with me is about context — knowing the difference between a bigot who really means the word and an ally or member of the group who is just joking around. That’s something that the survey indicates kids understand: “The poll found that 54 per cent of young people see the use of the words in their own social circles as acceptable because ‘I know we don’t mean it.’ But when asked the question in a wider context, most said such language was always wrong.” I know plenty of queer people who are fine with their straight friends calling them “fag” and “dyke” because they know their friend doesn’t mean it and is poking fun at the stereotype rather than at them. I’ve even heard similar statements made about friends using racial slurs. But the same people would never hesitate to call out a true hater using those words to condemn those groups.

But part of the problem, and the reason I’m not comfortable completely dismissing the importance of language, is that you can’t always control the context. You can’t always know who else is listening besides your friends. Others could hear it and think you do mean it as a slur and be offended. Still others might actually be bigots themselves and take your use of offensive words as evidence that people out there agree with them. This is especially true online, the area where this study focuses. Who can tell whether YouTube comments full of slurs are being made by people who actually hold such despicable attitudes, or people merely mocking bigots? Nobody knows, least of all the bigots they may be trying to parody. It’s Poe’s Law at its worst.

And while gay kids may not have as much of a problem as adults think with anti-gay slurs, the survey found a bigger gap between African-American kids’ perception of the n-word compared to all kids, which suggests this isn’t universal:

“More young people (44 per cent) said they would be “very” or “extremely” offended if they saw someone using the word ‘nigger’ online but 35 per cent said they wouldn’t be too bothered and 25 per cent said they wouldn’t be bothered at all.

However, 60 per cent of African-American young people said they would be offended if they saw the word directed at someone else.

Overall, it’s hard to tell for certain whether to see this study as a good or a bad sign. Maybe we should just let the kids tell us.