By A.D. Hogan and Becca Kahn Bloch

Clothes are weird, magical things. They can make you feel invincible, giving you the confidence to pick up that girl at the bar — but they can also wrap you up in warm and fuzzies after a terrible breakup, comforting you with their oh-so-soft fleecy goodness and memories of times past. The right clothes can provide the secret password to getting in with a certain group—but they can also make you feel unique, differentiating you from the crowd. Whether they are off-the-rack, hand-stitched by your grandmother, found at Goodwill, or “borrowed” from a friend, clothes somehow give us this crazy way to express ourselves that’s kind of unlike anything else. And for queer people, figuring out ways to express ourselves is a big deal.

Knowing this, we made a documentary short, called gender, bespoke, about some of our favorite things: gender, clothing, and beautiful queer people. When we came up with the idea to make gender, bespoke, we were enrolled in a queer theory seminar. For our final, instead of writing a paper, we wanted to collaborate on a creative project —figure out how to take hyper-academic queer theory and translate it into our everyday lives. We both love fashion—(A.D. has this thing about obsessively documenting what she wears every day on her tumblr) — and we’re both super interested in gender, performativity, and queer presentation. And so we thought, what better way to show how queer theory manifests in our everyday lives than to look at what we wear? I mean, come on: we all know that queer women are obsessed with their clothes. Just take a look at any one of the hundreds of queer/lesbian fashion blogs on the interwebz right now. So what’s the deal? Is it just that queer ladies are super fashionable? Well, yeah. Duh. But there’s clearly something more going on here; queer women have an attachment to their clothing that transcends fashion and delves into issues of identity, legitimacy, and performance.

gender, bespoke provides a glimpse into the closets and minds of a few queer women at Oberlin College, a small liberal-arts college in Oberlin, OH. Bespoke is a term that means “handmade” or “made to order,” and so bespoke clothing is different from ready-made clothing. Ready-made clothing is what nearly everyone wears; it is made in general sizes (M, XL, 16½, etc.), and it is sewn by machine. The stitches in ready-made clothes are very tight and exact; they are stapled and forced. The stitches in bespoke clothes, however, are looser and “give” more. Bespoke clothes move and adjust and change through time as they move with one’s body. gender, bespoke, then, suggests a self-made and continually changing gender identity. The film traces the “stitching” of gender, identity, and fashion of each person.

The questions we explored in the process of making this film include: How does a gay/lesbian/queer person gain legitimacy through the daily micro-performances of getting dressed and being dressed? How can a literal closet affect the metaphorical closet, disclosing one’s identity to others? What do the interactions of gender, orientation, class, race, dis/ability, citizenship, globalism, etc., suggest (or perhaps explicitly convey) about one’s identity? What does clothing signify? Does clothing need to be worn to have its significance? Is this movie about the clothes or the person? Can you separate the two? What does clothing signify to the wearer? To “straight” people? To other queers?

Of course these questions are much larger than our short documentary conveys, but they serve as guiding markers throughout our work. We consider gender, bespoke to be one conversation in an ongoing dialogue about performativity, gender identity, and the everyday politics of queer.

We came at this project from very different perspectives. In some ways, the two of us are pretty similar. We’re both white, economically privileged (to varying extents) cis-women who identify as queer and attend an elite private college. But as far as how we dress, and how we relate to our clothing, the similarities end there. Becca identifies as a femme, with a closet full of dresses, cardigans, and scarves. A.D. likens her style to “sassy frat boy”—masculine prep with queer flair.

Though we both have pretty different styles, we both consider fashion to be a vital part of our coming-out stories, and how we negotiate our queerness.

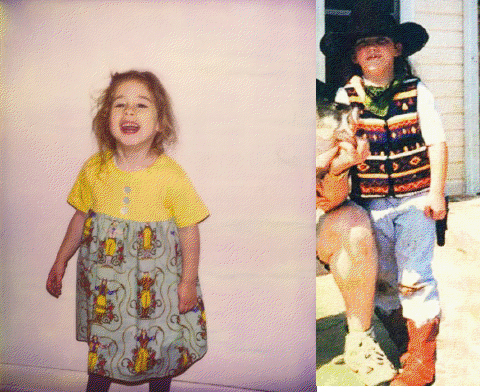

For Becca, it went a little something like this:

I like to think that I’ve always been femme. Even when I was three, I could rock a cute sundress and tights like nobody’s business. Of course, there was the requisite tomboy/sports/cat-lady phase in middle school (hello baggy shorts and non-ironic cat t-shirts), but that was short lived.

During my sophomore year of high school, I first came out to myself, had my first (secret) girlfriend, and started hanging out with a group of cool, artsy seniors. All of this made me way more confident in myself, and subsequently affected my style. Gone were the baggy shorts and clogs (seriously? I know. Let’s just not talk about it.), and in their place was a closet full of skinny jeans, silk skirts, and of course the requisite contingent of American Apparel t-shirts. Once I started coming out—first to myself and then to others—I really started reveling in my femme presentation.

I like to think that it was because I finally felt like I could truly be myself, and that I didn’t have to hide anymore in nondescript clothing that covered me up and hid the real me from everyone else. But I also know that part of me knew that coming out meant that I would be susceptible to a lot of judgment, and so dressing femme was my way of combatting the stereotypes, and establishing myself as a lesbian on my own terms. When I was first coming out, it was comforting not having to constantly worry about being outed by my clothing. Having the safety net of femme presentation made my coming out process easier for me; skirts, heels, and makeup afforded me more control over who knew what about my identity, and when.

As I became more comfortable with myself and with my sexual orientation, I toned down the femme a bit. (A trip to Israel introduced fisherman’s pants to my wardrobe in a major way, much to my later chagrin.) But I realized that femme for me wasn’t just a safety net or a protective shield—I loved how I felt in dresses and makeup; they made me feel hot and confident and ready to take on the world. They made me feel like me.

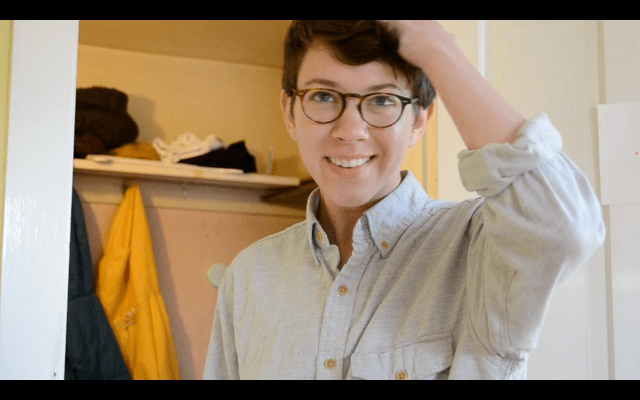

But for A.D., it was a different story:

One of the first things I tell everyone is that I’m from Texas. Growing up, I was actually a cowgirl. I had two basic looks: cowgirl and sporty. If I wasn’t in jeans and boots, I was in baggy shorts and beating the boys in races. This didn’t change for years. In high school, I rocked skinny jeans and white v-necks for years. I loved the simplicity of this outfit. I could play viola in it; I could go to church; I could go to cafes. It said nothing, which is exactly what I wanted. I wanted to erase any signifiers of my evolving gender identity and sexuality.

During my coming out process, I was extremely paranoid about being read as a “lesbian” both by the community and the world at large. I didn’t want everyone to know my business; I just wanted the cuties to know my business. (Oh, come on. You know you want the same thing.)

Collared shirts and leather boots were definitely a good first step. I then realized that the long mass of curls on my head rendered me illegitimate and invisible in a lot of queer spaces. I was continually asked, “So, when are you cutting your hair?” and “Are you femme?” or even, “Why do you wear masculine clothing and have long hair?” (as if my gender incongruence was, like, the pinnacle sin against the Goddesses of Gaydom).

These questions lead my current rebellion; I’m a founding member of the long-hair-don’t-care club. My hair and my clothing are statements that complicate androgyny, female-bodied-ness, gender, class, and race in ways that are not at first apparent. I dress like a frat boy, but I queer my look with plenty of sass and gender nonconformity along the way. My clothing is definitely an attempt to pass as an identity (rich, white, privileged) that I sometimes occupy (white, masculine, educationally privileged), and sometimes don’t (rich, male).

For both of us, what we wore and how we wore it was incredibly important during our coming out processes. We were trying to figure out how we wanted to present ourselves, and what we wanted the world to see at first glance. Even though we headed in different style directions, both of us shed our non-descript, identity-hiding clothing after we came out. And both of us look to our clothing now to help us negotiate our queer identities in the world.

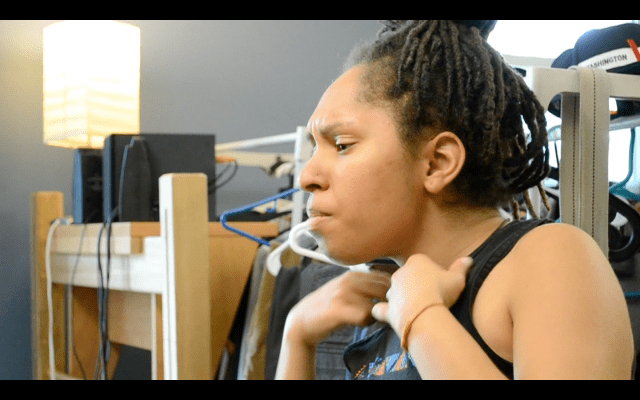

Making this documentary was a really exciting process for us because we were able to learn about other queer women’s complicated relationships with clothing. Just like us, the subjects in our film are constantly negotiating their queer identities through their clothing, and just like us, they consider their clothing to be intimately connected to their gender presentation. The five women (including A.D.) that we interviewed discussed topics such as passing, visible and invisible femininities, looking “gay enough,” and getting dressed as “drag.” It was such an incredibly cool experience to see our own thoughts and emotions about clothing and queerness reflected in what our subjects were saying, and also to hear about new issues and new ideas that we hadn’t personally experienced.

For Becca, Naomi’s discussion of femme invisibility was particularly resonant:

I can really identify with what Naomi said about how being read as straight can feel like “a certain erasure of your identity.” Being read as straight because of my dresses and makeup was comforting in high school when I was still coming out, but when I got to college, it was a problem—not an asset. It was frustrating to be overlooked in queer circles, or to feel as though others were wondering why that straight girl was there. Aside from the practical problem of being unable to get a date because everyone thought I was straight, being read as straight barred me from feeling like I was part of the queer community.

I wanted ways to differentiate myself from the pack, to let it be known to others that I was queer. And so I adopted some new—or emphasized some existing—queer signifiers, which Naomi and Hanna mention in the film. Industrial piercing? Check. Shaved part of the head? Check. Some new lids and a couple pairs of kicks? Double check.

Now don’t get me wrong—I still wear dresses. In fact, I pretty much only wear dresses now. (True story: some of my closest friends at Oberlin can’t remember ever seeing me in pants because I actually have not worn a single pair of pants while at college [late-night cramming for final exams sweatpants excluded].) So yeah, I’m still pretty femme. But I’m a different kind of femme in college than I was in high school.

For A.D., it was discussions of masculinity that were really interesting:

I really loved the masculinities that Meagan, Taylor, and Hanna embodied and discussed. Hanna talked a lot about feminine masculinity, and how they identified with gay male culture more than queer female/woman/FAAB/trans* culture. I am still so intrigued by this concept of non-female femininity found in gay-male culture, as well as the similarities between gay/lesbian/queer cultures.

I also really loved Meagan’s discussion of failure, and how she failed to be masculine enough. Through coming out, I continually felt like I wasn’t queer enough, out enough, gay enough, smart enough, alternative enough, or just simply enough. Once I started dating, I felt insufficiently queer/masculine/dominant in the bedroom, in the club, and in conversations. Through confessing her acceptance of her “shortcomings,” Meagan invited me to reconsider my own “failings.” Also, her term “sissy butch” is one on my new descriptors. Love it.

gender, bespoke is our attempt to show some examples of queer fashion and gender identity. Even though all of the subjects are Oberlin College students, we think that queer experiences are relatable across a broad range of identities and experiences, and that gender, bespoke is able to resonate beyond the borders of Oberlin and into the greater queer community. We also think it’s important to note that we deliberately chose not to include any trans* subjects in the film. When we were first planning the film, we talked about this at length—with each other, with our friends, with anyone who would talk to us. We had concerns about appropriately representing trans* bodies on film—we didn’t want to fetishize and we didn’t want to tokenize, especially given the history of trans* bodies on film. Ultimately, it came down to us, as queer cis-women, and as filmmakers, not feeling comfortable with potentially objectifying or otherwise exploiting trans* bodies.

The process of making gender, bespoke has been an amazing one. We’ve learned so much about ourselves, about our friends, and about queerness and gender presentation. It definitely got a little crazy at times—(frequent visitors to the editing studio included a bottle of whiskey and a healthy dose of insanity) — but it really has been eye-opening for us to hear other queer women’s stories, and be able to render them on film for the whole community to see. Plus we picked up a few fashion tips along the way.

Ultimately, what we took away from making this movie was that, for queer women, clothing is about much more than what you’re wearing. Clothing allows us to create an identity for ourselves—and to control how other people view us and consider us. What we’ve learned is that while each queer woman’s story may be different, clothing probably plays an important part in every one.

To get in touch with A.D. Hogan and Becca Kahn Bloch, email genderbespokedocumentary [at] gmail [dot]com

Comments

Megan’s glasses? Where do those bad boys come from?

God I remember trying on a pair like that when I got my glasses, but they just DIDN’T WORK for my face and I was so sad. :(

I love this project! I love talking about clothing and identity and learning about how people’s clothing/gender presentation are key to the way they present themselves to others. As an avowed femme & fashion fanatic, I love to play with my femininity (sometimes I feel like my affection for pink is just a reaction to all those people who were like “ick, that’s so girly”). And I like to get into extremely feminine spaces (hello, lingerie) and queer it up a bit. I can’t wait to actually watch the video later when I get out of work.

wow i loved this so much!

Gahh, Naomi kept saying things that I’ve been trying to say forever. “Little bits that are signifiers.” I found that I appreciate my piercings for this, and I wear a little rainbow bracelet, especially whenever I’m going out so as to not attract the wrong people. “A certain erasure of who I am” I feel like I constantly have to fight my femininity to be noticed by queer women and I usually only attract men which isn’t my goal. It makes me feel uncomfortable and left out a lot. But it’s how I like to dress. Great video! Thanks for sharing.

i really liked the whole thing about being called sir, and how it feels kind of wrong because i’m not a man, but also really right, in that it validates my non-femininity and presentation as being masculine-of-center.

it only bothers me when i’m at work and i’m wearing a fucking name tag and people are too lazy to read the damn thing. sigh.

Same here. I’m seriously freakin’ femme, and am attracted to other femmes. Besides that being natural for me, I also like to challenge that kind of gender-binary expectation of lesbians where we’re stereotyped as invariably masculine, or that heteronormative expectation that in a queer relationship there must be a ‘male’ and a ‘female.’ I just find the astonished reactions of straight people also kind of interesting. As long as you’re in northern Europe or a blue state, anyway, and less concerned about your safety.

It’s kind of interesting, but when I first was coming out to my mom, she said that she assumed one was a lesbian because one like that feminine look, was attracted to femininity instead of masculinity, so I had to enlighten her on the fact that a lot of us like girls with a masculine or androgynous bent as well. But I think that’s interesting, because it makes me wonder what “most straight people” actually do believe about what we find attractive. I have no idea.

Hey everyone. I’ve never considered myself queer because I do not seek out romantic or sexual relationships with women. However, since my best friend’s dad came out as trans after their mother died and started dressing as a woman and dating men, with her I started to reevaluate my thoughts around gender and sexual preference. Neither of us were bothered by her dad’s decision but when my friend struggled with “I’m not calling him mom!!!” I began to wonder what preconceived notions did I have about gender and sexuality. I don’t know how I ended up being so open and accepting of the different ways humans are different from each other and how they choose to express that but I’ve always been aware of a queer community and took a child’s prespective of live and let live. At puberty I realized that while I found women to be more physically attractive I wanted or assumed a heterosexual identity. I started to question this in college you’d think I’d have experimented or something but I didn’t. I didn’t actually know anyone I was attracted to-male or female. I also decided since I couldn’t see myself as a woman actually performing the sex act on another woman I probably wasn’t a lesibian or even bi which honestly disappointed me. I’m not even sure why I was disappointed. Like I was comfortable with the idea of kissing, cuddling, even being nude and touching and wanted that kind of attention and affection but just had this strange line of but not actual sex. I’ve always wondered if it was social. And straight girls can be confusing. I’m black…and some of the white girls I would hang out with would kiss me on the mouth if we were at a club. And they’d kiss each other. And I’d always think kissing casually should always be like this. But they didn’t really mean it. It was a show for men! My black friends never did this and I felt a strong taboo sensation about it. I stopped hanging out with them because it just felt like lying. I ended up feeling used. I want kisses to mean something. Like when I kiss my sister goodbye with a peck on the lips. I don’t want to bang my sister but I love her and I gave her a peck on the lips. Why isn’t that ok? Why isn’t it ok with my friends?

But I decided to comment because I didn’t just find myself attracted to femme women but also “butch” women. I decided I just like who I like and I want, need, crave certain kinds of intimacy, especially with women. I prefer to build strong long term intimate relationships with women that are not sexual. Sex is with men. But I realized my female straight friends did not share my point of view and did not understand why I wanted to be so physically close to them. I grew up in the performing arts and have noticed performers allow themselves to be physically close to each other in a way other people do not. So when I drifted away from the performing arts my cuddle partners disappeared. My best friend (whom I love dearly but she’s completely straight there’s no grey area with her) had to literally be taught that if we were going to be friends she needed to hug me. Sometimes for a long time.

And strangely this is the first time I’ve said all of this together in a clear fashion. And I won’t insult all of you by saying hey guys I’m one of you! Because obviously something else is going on but this project is really interesting.

So Samantha, you made me think about all this because you pondered, “what do straight people think we find attractive”? I assumed everyone queer or other, like me, liked what liked you and what turned you on-whatever that is. I assumed that for every woman who likes femmes there were those who liked butch otherwise why did they exist. Someone likes them. Because when people ask me what’s my type and I think about who I’ve found attractive it’s rarely had to do with their looks. It was always how they made me feel. Like the picture of Meghan made me go, “Aww I want to snuggle right up against her neck and take a nap.” Sure I have the same thought about my cats but that’s what I like to do with people I’m attracted to. I want to cuddle them. I want to feel their warmth. I want to feel loved by them. And I feel loved with hugs and touches-sexual or non sexual. And as long as you look like you can love me I’m game. Then can you talk to me and make me happy and get along with me. I’m game. Sex is something else. See if it weren’t for the sex I’d totally identify as queer.

So while I may sex a man I may not feel loved by him. And may not seek him out sexually to feel loved either. Sex is about dominance and control for me and sensory overload. I do not want to dominate and control women. Therefore I do not want to have sex with them. But I do want to love them. For that I may instead go get a hug from my best friend, a completely straight gal who always has looked at me sideways and from time to time and will ask me… are you sure you’re not bi? Always in a are you secretly attracted to me sexually? I always hesitate because I know why she’s asking and see the truth in the question but I end up saying no. It’s like yes but I enjoy loving you, I don’t want to have sex with you but if I were actually male I’d marry you. And since gender reassignment surgery would not allow me to produce sperm to give you children, I won’t consider it but if it could for you I’d reassign my gender, marry you and give you the children I know you desire. I’d do anything to make you happy because I love you. But it can’t so I’m content being a woman.—Like, what does that even mean???— I don’t know.

So I don’t quite fit on the hetero spectrum either. I don’t really know where I belong and honestly its not of real import but I have to say I’ve enjoyed hanging out with all of you here.

Shanel, wow. Thank you for articulating all of this. I can relate to a lot of what you’re saying, and it is so gratifying to see that my confusion is not as isolating as I sometimes feel. My situation seems to be complicated by the fact that I have never really had sex with a man OR a woman, and I really don’t know what the fuck to do about that at the moment. I don’t feel comfortable going a casual one-night-stand kind of route, but I fear getting deeper into a relationship and not having picked the “right” gender. Jeez. I got some shit to work out! Anyway, I just wanted to thank you for taking the time to express your feelings on gender and attraction and intimacy. This has, and will, help me continue to consider how to work this out for me. :)

Suzanne thanks for letting me know that by sharing what’s going on with me it’s helped you. That actually means a lot. :)

As a tomboy femme, who is attracted to boyish girls, I feel your pain. I seem to attract a lot of femmes, and I just wanna be like, oh girl, trust me, I’m not want you want.

“One of the first things I tell everyone is that I’m from Texas.”

You and me both, sister.

ditto. luckily i got out.

I wish A.D. would clarify what “trans* culture” is. There is no such thing except generalizations/assumptions which end up making large parts of the trans community invisible. If she meant certain very specific masculine-based trans guy or transmasculine looks I wish she would say that instead of using some global term like “trans*.” Btw, there are LOTS of trans guy who are very connected to the community of gay cis men, so are they not part of “trans* culture” not to mention many MAAB femme/transfeminine spectrum” people?

what i was trying to say is that hanna strongly identifies with hegemonic gay male culture. i used “trans*” because it is global. i didn’t want to narrow it down. my response to hanna is in part a response to the documentary, but also in response to our friendship. i intentionally left room in the explanation because of the ever-changing nature of both hanna’s experiences and my negotiations with queerness.

(language, in its specificity, can fail because the signified (through seemingly exacting terms) fails to be to accurately portrayed through the signifier. had i been more exact, i would have left so many other experiences out of the “signified.”

language, in its specificity, can fail because the signified (through seemingly exacting terms) fails to be to accurately portrayed through the signifier. had i been more exact, i would have left so many other experiences out of the “signified.”

<3 this

AD, I get that your comments are specifically about the video and the participants in the video. And, while I see value in using semiotics to reexamine language, I think what I was talking about is an real life example of how being trans is reduced down to “style choices.” On a semiotic level, even using the term “trans*”… the asterisk which is overwhelmingly supported by queer-ID’d FAAB white educated persons (and not used by many others in the trans community) is instantly reducing trans identities into very specific looks and ideas of expression which profoundly invisibilize and minimize the huge spectrum of lives, colors, and identities within our community. (yes, even though the asterisk is supposed to be all inclusive, it is itself a signifier) While I realize in your environment you seem to see trans persons expressing in some fairly specific ways and manners, that isn’t so in the rest of the world. Please don’t equate being trans with culture or expressing style choices. I appreciate the statement about not not being qualified to represent trans bodies in the video but a) The omission is already a commentary on trans people and b) your intro to the video went several steps beyond that disclaimer.

AD: I just created an account with Autostraddle because I had to say thank you for creating this film! I really appreciated it! Also, re: your parenthetical in your above comment… do you happen to read Lacan?

hi hi hi,

thanks for the love. i have read lacan and i find a lot of his work useful. so glad there are other theory nerds in the world! :)

Seriously impeccable timing, Autostraddle. Just yesterday I was fretting over what to wear to meet my new boss for my new job. What I wanted to wear initially I was worried looked “too gay” and I wasn’t sure if that was what I wanted my first impression to be. Then I worried that wearing a dress would present me as something I am not and give an even weirder first impression. It was seriously about two hours of trying on clothes.

Absolutely! Do I look too butch for a job interview? Is it safe to come out as gay just from looking at me for two seconds? Do I look too feminine wearing pumps? Will it be weird, if I wear a dress for the interview, but a suit on my first actual day of work? Do I even want to hide that I’m gay? Do I want to work at a job where people look at me funny for being queer? Can I afford not to take the job just because I don’t feel comfortable in a feminine work uniform?

Sooo many questions and so many feelings involved. I recommend “Looking Like What You Are: Sexual Style, Race, and Lesbian Identity” by Lisa Walker. It has really helped me sort through my closet (that I don’t want to be in anymore).

“all gender is drag.” WORD. loved this.

Aw yeah, Oberlin represent!

Wow, I was quite surprised to see my own clothing choices and expressions in A.D. in the video since I didn’t get that vibe from what she wrote.

I guess I approach that same style from a more feminine perspective.

Wait, I’m sorry, did I misunderstand or did Taylor identify as Tran* Masculine. Taylor’s line is: “I think the straight world doesn’t know what to do with a trans* masculine black body.”

Am I getting that wrong??? Is Taylor speaking about Taylor’s body or in general???

I question this in contrast with the disclaimer at the beginning of the video…

hi,

taylor, at the time we filmed this, did not identify as trans*, and i think they were saying that the world does not know what to do with a body that could be/is read as transmasculine, or trans*.

these definitions are personal, and are understood within a vast assemblage of different factors, like race, class, ability, geographic location, etc.

these definitions are personal, and are understood within a vast assemblage of different factors, like race, class, ability, geographic location, etc. *** and should be understood as personal reflections of experiences. though we (bkb + ad) try to be understandable, we (all of us) should also acknowledge ourselves as living beings and give ourselves room and space to change and become.

Agreed, that we are continuously evolving/grooming/redefining our identities and that we must absolutely be given the space to transform as we see fit.

And thank you for clearing up the confusion about that Taylor’s meaning.

I was actually fairly disappointed in your decision to exclude trans people based on their gender identities. I felt that this was in direct contradiction with what you were trying to achieve in the documentary. While I admire your desire to show respect for trans identities and bodies, I thought that this exclusion was disrespectful.

I think that almost everyone on autostraddle can identify with under representation and the desire to be seen and heard. Trans people are PARTICULARLY under represented. I don’t assume that it’s your personal responsibility to represent trans people in your work, but specifically excluding the trans community is an act of discrimination. It would be similar to what you would be doing, if, as two white women, you chose to exclude any people of color because you felt that it would be tokenizing, fetishizing, or that you were otherwise ill-equipped to represent experiences that are different from your own. In fact, I was fairly offended that you thought that the simple representation of a trans voice would somehow be inherently fetishizing or tokenizing. The fact of your documentary is that you WERE representing experiences that were different from your own, and I felt that the arbitrary line that you chose to determine which experiences were close enough to your own to be represented and which experiences were TOO different from your own to be represented was disrespectful.

But that’s just my two cents. Otherwise, I love the discussion that your having and I loved hearing the voices in the documentary. I also loved getting to see the faces that went with the voices.

Imaani, thanks for your input. Whether to include trans* people was something we really struggled with, and although we are happy with how the film turned out, we’re not saying it’s perfect. Had we included trans* people, the film certainly would have been different, but that’s not to say it would have been better or worse. Just different. If we continue this project into a more long-form piece, it’s definitely something we’ll reevaluate.

But thanks for your opinion! It’s great to hear from people who care, and it definitely informs our thoughts on the subject!

-BKB

Becca’s story here and the bits about femmeness in the video really resonated with me. As a FAAB, trans*, lady-lovin’ femme, dressing up is an everyday battle ; I’m constantly torn between getting people to stop reading me as a bunch of things I am not (a straight cis girl) and taking me seriously when I tell them who I am, and getting to just, well, be me. Who do I dress for, me of them? What do I dress for? Acceptance or confidence?

Sometimes dressing up feels like going drag and putting on an identity as a show, and sometimes it feels like expressing my inner self, and sometimes I just don’t know how I feel and whether or not I should settle once and for all for either one of those things.

To a bigger extent, I also have all of these complicated feelings towards my body too, but that’s another story – at least clothes can be changed at will.

Oh, and I also really liked that Becca and A.D. a) seriously considered adding trans* people to the video and b) decided not to do it. I appreciate the intention to be more trans*-inclusive but I’m tired of cis gay people talking for/about us.

Hi!

“As a FAAB, trans*, lady-lovin’ femme, dressing up is an everyday battle”

True that! I love ladies, gentlemen, and others, and am also a bit femme-y, so yes, this is difficult. I can’t tell if I’m read as straight, gay, bi, cis female, trans male, or cis male most of the time. I’m…pretty sure…most people (strangers, I mean) regard me as a straight cis girl most of the time, which is depressing.

“I appreciate the intention to be more trans*-inclusive but I’m tired of cis gay people talking for/about us.”

I could deal with more people talking about us, period. It would be nice if it were other trans* folks, but as long as it’s respectful I’d like other people to consider our issues as well. We’re even more of a minority than The Gheys, so we really need the visibility. The gender revolution is for EVERYONE, though. Not just us.

Re: your last paragraph, yeah I agree. The reason I’m glad they didn’t is because when gay people do it, it often comes across as a) they feeling entitled to talk for us because we’re all part of the so-called “LGBT community” (although there isn’t such a thing) or b) they feeling a sort of moral obligation to talk about us even though they’d rather not, again because they feel they have to represent the T in LGBT.

In many cases, it ends up being half-assed and full of problematic language and statements because they didn’t really considered the fact that they’re talking about an entirely different group with different needs and challenges.

So, yeah, I’m all for cis people talking more about us and educating themselves on the subject before doing so, but if someone feels they don’t have the required knowledge to talk about us respectfully and accurately, I’d rather they abstain from it instead of going for it anyway and butchering it because they feel like as cis queer people they “have (the right) to”.

Dear A.D.: rock on.

Hell yeah AD! :)

I really liked this! Also hell yeah to the long hair + ties combination. I’m tired of feeling like my hair length invalidates my (weird, queertastic) masculinity.

This is so great, it explains so much of the stress that I feel when I get dressed. I love wearing dresses and presenting more feminine but I often find myself choosing a more masculine style so that I don’t attract unwanted attention or get read as “straight”.

Amazing project — and you are all GORGEOUS!

Thank you so much for writing this article and making us aware of your film! I loved everything that was talked about.

Some of the things written in the article reminded me of some feelings I have had. Of kind of feeling sometimes when I’m wearing a skirt like I’m in drag, if that makes any sense, which is a really interesting feeling to feel as a cisgender woman. I remember the first time I felt like that, it was this really surreal feeling, like I didn’t understand my body anymore. I couldn’t connect with what I was seeing in the mirror, and sometimes I still feel like that. I’m still trying to work out what I want as far as gender presentation and how I feel about myself inside. I can sometimes really enjoy femming it up, but it does kind of feel like I’m just pretending, like I’m playing dress-up (and having fun), rather than being myself. So it’s not necessarily an uncomfortable feeling, just one that definitely feels like a performance. And like a performance, I never want to do it for too long, even if it’s fun to do for a short while.

And also sometimes I do feel maybe my brand of femininity is something closer to the non-female femininity mentioned in the article. I really feel like that sometimes. It feels feminine, but different, from a different perspective or something. Maybe that’s just the queer aspect? Again, I’m not sure. I’m still trying to figure it out. But I loved reading this and watching the video and feeling like I’m going to figure it out at some point. :)

“Of kind of feeling sometimes when I’m wearing a skirt like I’m in drag, if that makes any sense, which is a really interesting feeling to feel as a cisgender woman. … I can sometimes really enjoy femming it up, but it does kind of feel like I’m just pretending, like I’m playing dress-up (and having fun), rather than being myself. ”

This.

Yessssss Oberlin!

So sad I’m on leave this year. I’m gonna miss that place (even though the queer community there never really noticed my existence).

Awesome stuff. Personally as a British person who was required to wear a tie to school I have a difficult relationship with that particular item of clothing. I mean, I can tie the knot in my sleep, and I appreciate its certain smart masculine je ne sais quoi… but on the other hand it feels unisex to begin with… and I associate it with teenage angst, humiliation, and being required to wear an ankle-length pleated skirt.

Kudos also for the interesting comments in the Judaism video on the same channel. Especially the bit about imagelessness and experience. Chimed with some of my complicated thoughts on the subject.

club. My hair and my clothing are statements that

complicate androgyny, female-bodied-ness, gender, class, and race in

ways that are not at first apparent. I dress like a frat boy, but I queer

my look with plenty of sass and gender nonconformity along the way.

My clothing is definitely an attempt to pass as an identity (rich, white,

privileged) that I sometimes occupy (white, masculine, educationally

privileged), and sometimes don’t (rich, male).”

YES. YES. YES. I am so feeling this. I also feel most comfortable in simple, poser-y Santa Cruz skater boy clothes, or the cowboi look, but I will not cut my hair to fit any sort of policing. My hair isn’t long but it will never be shaved or t&s style. I don’t feel comfortable doing that (mostly because I have a huge misshapen head and very thick, wavy hair), and anyway I LOVE my hair the way/length it is.I cut it myself because I don’t like other people, even hairstylists, doing something to my image.

As for passing in the mainstream…I do that under the radar invisible thing as much as possible, for much the same reasons. Who I am is my business, not the stranger on the street’s. Fortunately I work in a place where tough, stainable clothes are practically required, and in a friendly enough place that I can wear the clothes that make me most comfortable.

Thanks for this piece, it’s so GOOD to know others feel as I do.

Oh man, clothes. Clothes are a huge thing for me, for just the reasons listed. Being trans and a dyke, I have to manage people’s perception and judgement of me just to get the most basic of identity’s recognized. For the most part, I’m really pretty femme, but I do enjoy queering it up a bit, like wearing boots with dresses or having very clashy colors. The problem is that if I dress super femme, like I usually enjoy doing, I’m hardly ever gendered correctly and am assumed to be a gay man. The same that happens if I dress very butch so I have to navigate the push-pull of masculine and feminine clothes which, while very frustrating at times, is fun in a puzzle-y sort of way and has really developed my sense of what looks good on me. Having such a huge awareness of what clothes I wear makes it sort of awkward for me when I get random compliments on my clothes because I put so much thought and meaning to them.

Awesome project! I am very frustrated that, every day, I feel like I have to choose between clothing that truly reflects my personality (on the femme end of the spectrum) and clothing that identifies me as a queer person to fellow queers. Great to see this subject being tackled.

Also, Meaghan, I have a huge crush on you. Am I even allowed to say that?

That is all.

I loved this! how we use clothes as an extension of our gender identity is really interesting to me. I remember back in high school, when I still dressed like the other girls pretty much: I always felt like I was faking it, and I felt like people could tell. Even when I knew I looked good, I still wasn’t comfortable. Now I dress masculine, and not only am I comfortable, but I now enjoy fashion and feel like I can have fun with it.

Thanks A.D. and Becca, and thanks AS for posting. (more like this please!)

Well… I don’t really think there’s a trans culture per se. There is a community, but the culture is different for every transperson. For example, I have a MtF friend who likes guys and identifies as hetero. She just wants to be a straight and plain girl. I’m MtF trans, but I identify more as Lesbian. I tend to think of myself as a woman with a hormone problem. (I’m working on fixing that.^_^)

I keep reading Meagan to rhyme with Smeagol, I think the Hobbit trailers are getting to me

Awesome project, thanks for sharing!

I loved this! As a queer woman I have a unique style, but I’ve never had a way to explain it. Thanks for doing this, I’ll definitely be sharing this with some people.

“Since I can’t run around naked . . . my clothes are the next best thing.” LOVE.

Can someone please define FAAB for your non queer cousins?

I can’t really speak for GV, but I’m guessing Female Assigned At Birth.

Interesting. I can see why creating a term for that is important here.

Thanks for what yall are doing. As many of us have said, you piece resonates with something we may have experienced. I really appreciate the desire to take your gender-theory to the masses. Also just grateful again for Autostraddle and the space it provides for people to be intellectual and still human. To realize that these things are not so separate and that we can all talk about them wherever we are coming from. Keep up the great work.

p.s. you are all adorable and I wish I knew you!

HI AD, this made me really happy because this took place at Oberlin and I go to the College of Wooster, which means we’re basically next door neighbors in the world of liberal arts colleges. Also, Wooster is hosting a Global Queerness conference this October and all the Oberlin queers should definitely come! We can be academic and have a huge party.

definitely going! i’m (supposed to be) working on my abstract/paper right now… andddddd autostraddle is the perfect way to procrastinate.

Is anyone else tired of gender theory? I do not mean this in a PC is dead = everyone is a target type of way I mean it in a way that if I see the word “cis” it very often makes my skin crawl. It just reminds me of wealthy, white-people with access to opportunity trying to beat a culture by over analyizing every detail to death. Yes the video was nice, and it does make me happy to know that the younger generation is turning it out in ways not done before, but at the same time the more we continue to label ourselves as anything more than queer, the more annoying the conversation gets. Yes it is important to understand that general society has not even closely caught onto this thought, but it will happen as long as people continue the path of being true to themselves and are honest. My wish is that gender theory will be irrelevant in the (near) future, and with it people will wear whatever suits them in the moment and not everything will be a GD political statement. To the students in the video; this rant is not a reflection on your project per se, but a generalized feeling that your video incited me to share. You’re all adorable!

Amen!

this video was actually a response to a course on gender-theory. (i personally didn’t want to do a hyper-academic response to the class; i wanted to talk to cuties about clothing. :)!)

studying gender theory is a privilege. but i have found that it can be useful to think about gender in both “high” and “low” ways (like butler v. halberstam). and for me personally, gender theory was super exciting because it gave me the academic lens to think about my clothing/gender. theory is also very constrictive in certain ways, because i was thinking about everything in theoretical terms for like.. 6 months? i think gender theory is pretty necessary to deconstruct hegemonic masculinity and male privilege, until true equity (different than “equality”) is achieved, which seems essentially impossible.

anyway, glad you enjoyed the video!

I sort of wish this video was more of a fashion show. In addition to all the great discourse.

Meagan is so adorable :3

oh wow i really loved this

Man, this is a pretty crazy project. How can it even be called “Gender, bespoke” if it is literally trans-exclusionary? Queering gender IS about transcending gender. How can a project be about female masculinity if masculine-of-center trans people, butches, nonbinary people, and trans men are left out?

Sounds like the makers of this film only consider all-the-way-transitioned, hormones and surgeries, binary trans people as transgender. But that’s not The Trans Experience, it’s only one of them. It’s also kind of uncomfortable to read a supposedly aware person refer to trans people as “trans bodies”. If the project is not about bodies but gender and self-expression, why focus on trans people’s bodies?

I guess it’s good for cis women, but this kind of thinking only drives a bigger wedge between cis and trans people by making the former think that there’s a huge difference. We’re all just people and we have more in common than what this article gives off.