On Sunday, The Guardian‘s Sandra Laville published an in-depth report on the crisis of women’s refuges being shut across England and Wales. Between austerity-driven funding cuts and changes to government tendering processes that favour “more efficient” or “streamlined” (read: cheaper) generic services, refuges that provide specialist, therapeutic services to women fleeing domestic violence are struggling to stay open.

In a meeting with Home Secretary and former Minister for Women and Equalities Theresa May, women’s groups raised a number of concerns:

- The breakdown of the national network of refuges through local authorities imposing limits on the numbers of non-local women able to stay in them

- Time limits on length of stay

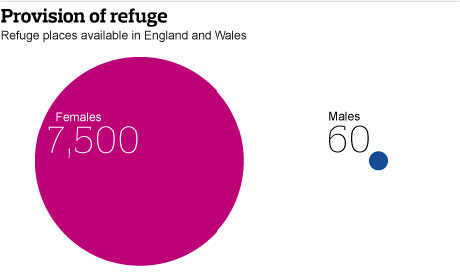

- Funding cuts because refuges do not take men

- Refuges being shut without alternative accommodation being provided

May claims that “there was a great deal of ignorance about the way domestic violence services were commissioned by local authorities,” but has repeatedly refused to “ringfence” or earmark funding nationally for refuges. The government has ended central funding of most DV support services and devolved responsibility to local authorities across England and Wales. Facing increasing demand without secure funding, the 2013 UK CEDAW Shadow Report (produced by a coalition of 42 women’s and human rights organisations) warns that access to specialist DV services, refuges especially, are becoming a “postcode lottery.”

Why Refuges?

The first women’s refuge opened in 1971 in Chiswick, west London, born out of a feminist movement that refused to be content with DV being hidden quite literally behind closed doors and recognising the unique concerns of women and children affected by violence in the home. In the words of Sandra Horley, Chief Executive of the charity Refuge:

Refuges are so much more than a roof over a head. Lives are transformed — specialist refuge workers support women to stay safe, access health services, legal advocacy and provide immigration advice.

Refuges also provide peer support — women are able to share their experiences and understand what they have been through. They realise, often for the first time, they are not alone, and they are not to blame for the abuse, Empowering women and children to overcome trauma and rebuild their lives is highly specialist, intensive work — it takes longer than a few weeks.

Women’s refuges in Exeter, Gloucestershire, Cheshire, Dorset, Somerset, Sheffield, Nottingham, Leeds and Leicestershire — just to name a few — are now being shut down in favour of non-specialist accommodation provided by housing associations and others, or nothing at all. Those that remain open have caps placed on funding or the number of beds that can be given to non-local women, or are asked to reserve beds for male victims (even if they’ve never had any men referred to their services). Local authorities are also increasingly focusing on early intervention and prevention strategies.

Restricting services to local women doesn’t address the needs of those who need to be as far away from perpetrators as possible to be safe, which is why charities are fighting for funding for a national network of women’s refuges. Furthermore, generic emergency accommodation is in no way comparable to the specialist support provided by refuges. According to Polly Neate, Chief Executive of Women’s Aid:

Without refuges, abused women who cannot stay at home are removed to hostel or B&B accommodation with no emotional support, no practical help to rebuild their life and no feeling of safety. Many would rather return to a violent perpetrator and know the risks they and their children face than live in such accommodation. Many will think “better the devil you know.”

It’s true that there is no “one size fits all” solution to ensuring the safety and rehabilitation of DV victims, and education and prevention strategies, as well as alternative means of protection such as the new DV protection orders (DVPOs), are important. But opinions vary significantly on how effective these strategies are and none of them can be a substitute for refuges. Funding decisions cannot be purely guided by cost-effectiveness and an idea of what “should” be the best course of action for DV victims. Yes, ideally, victims of DV should be able to stay at home. Yes, refuges are often the very last resort for victims, and most would prefer not to use them. But the fact that they’re DV victims should tell us in no uncertain terms that these are far from ideal circumstances, and refuges serve the most vulnerable women and children for whom the home is the most dangerous place to be. If we remove this last solace, the alternatives are often homelessness, further violence or death.

Why Women’s Refuges?

The Guardian report chose to give special attention to refuges that are being shut down because they don’t cater to men, such as Haven in Coventry and The Wolverhampton Haven. The shift in focus to male victims has been condemned by women’s charities as misguided and deeply flawed.

It’s commonly quoted that 1 in 4 women and 1 in 6 men will experience DV in their lifetimes.

This statistic is taken from the British Crime Survey (BCS), and in particular, DV charities and authorities tend to rely on data from the 2004 review of the 2001 BCS by Sylvia Walby and Jonathan Allen. (The BCS is done yearly, but this report is thus far the most in-depth study into DV statistics in England & Wales.) The report found that “26% of women and 17% of men had experienced domestic violence since the age of 16” — the numbers are higher if you take into account incidents before age 16, i.e. lifetime rates — with “domestic violence” in this specific instance defined as at least one incident of non-sexual domestic threat of force, including financial and emotional abuse.

However, the reality is far more nuanced — and gender asymmetrical — than this statistic would suggest. Here are some of the key differences between male and female victims:

- Sexual violence is excluded from this measure of DV. 17% (1 in 6) of women and 2% (1 in 50) of men had been subject to some form of sexual victimisation since age 16. Women fear rape more than any other crime, according to their responses to the BCS. In 2002/3, 23% (1 in 4) of women were “very worried” about being raped, as opposed to 5% (1 in 20) of men.

- Women are more likely to suffer from repeat victimisation. Among people subject to 4 or more incidents of DV from the perpetrator of the worst incident, 89% were women. In fact, 32% of women had experienced DV from this person four or more times, compared to 11% of men.

- Women are also far more likely to experience multiple forms of violence. 3.3% of women and 0.3% of men were subject to all three forms of interpersonal violence covered in the study (DV, sexual victimisation and stalking).

- Women are more likely to suffer greater injury. Walby & Allen argue that characterising gendered rates of DV based on the severity of the act of violence (e.g. slapping < kicking < choking) gives an incomplete picture, noting that “when the impact of DV is the focus of analysis, there is greater gender asymmetry than when the focus is the nature of the act.” Again excluding sexual violence, they found that in the worst reported incident of interpersonal violence, women were more likely than men to sustain physical and mental injuries (75% women; 50% men), more likely to suffer mental or emotional problems (37% women; 10% men), and much more likely to sustain more severe physical injuries such as broken bones/teeth or severe bruising.

The report concludes that gender is a significant risk factor for interpersonal violence and that the risk is especially high if a woman is also young and poor. DV is not exclusively a women’s issue but it is undeniably a gendered one, affecting women disproportionately both in incident rates and severity of harm. Feminists have been arguing for decades that the link between gender and DV isn’t only correlative but causational: DV is a manifestation of systemic gendered subjugation at home and in society at large.

“Factors such as poverty and unemployment may exacerbate the violence, but they do not cause it. Domestic violence is an abuse of power. Men abuse women because they get away with it — as a society we tolerate it and therefore indirectly condone it.”

This is where women’s refuges come in. As mentioned earlier, refuges serve the most vulnerable of DV victims: those whose safety (and often that of their children too) can only be guaranteed by a complete relocation and who need dedicated therapeutic services to rebuild their lives. “By women, for women” services are often in the best position to provide this specialist care, providing women and children with safe(r) havens and both professional and peer support. Beyond this, women’s refuges are often strongly guided by feminist philosophies, which is important in recognising that DV isn’t only a personal issue (as police and policymakers would make it out to be) but a political one. It is the work of women’s organisations like these that have not only been responsible for directly improving the lives of countless women but also in fighting for DV to be taken seriously as a matter of public concern.

But What About The Men?

The divide between women’s and men’s groups in the DV sector is perhaps most clearly (albeit tamely) illustrated in a Guardian debate calling for answers to the question, “Should domestic violence services be gender-neutral?” In it, both Polly Neate (Chief Executive, Women’s Aid) and Glen Poole (Editor, insideMAN Magazine) conclude that gendered approaches are necessary, but with very different reasoning.

Male victims are certainly being underserved by the DV sector.

That being said, the phrase “men’s rights” comes with its baggage and for very, very good reason. For one, there’s the spurious use of the “1 in 6 men” statistic to suggest gender parity in DV rates, as debunked earlier. Men’s rights advocates, including groups like the ManKind Initiative and Parity, don’t only want greater support for male victims but to “remove gender politics” from DV discourse and legislation altogether. They argue that male DV victims are afraid to speak up because they will be disbelieved or expected to simply “man up” — all of which are absolutely true. Why? Because of the patriarchy.

Non-feminist or gender-blind approaches don’t work to solve DV, because DV is not simply an issue of a handful of bad apples abusing their partners. It is a problem that is deeply rooted in the gendered ways in which power is structured in society, particularly in the construction of the home as a “private,” feminised sphere in which abusers get away with doing incredible amounts of violence because it’s “just a domestic.” It’s exactly this attitude — the patriarchal distinction between what’s worthy of public attention and what isn’t — that second-wave feminists set about deconstructing with the mantra “the personal is political.”

At the same time, women’s organisations are far from perfect too. While women’s groups rightly point to the success of BME-specific services (which are now under even greater threat of having their funding cut) as proof of the value of specialist care and support, the same movement which founded women’s refuges is also responsible for the TERFism that denies trans women access to shelters that they desperately need. Broken Rainbow, the UK’s only DV charity that caters specifically to LGBT people, estimates that up to 80% of trans people experience DV. The violence that trans people, women especially, face both at the hands of their partners and family members as well as the legal and charity systems that fail to acknowledge their existence or even blame them for the very problem they’re fleeing — based on an essentialist view of “maleness” and “male violence” — is gendered violence too, largely policed within “feminist” spaces.

Either way, both sides agree that DV victims need support that is as closely aligned to their specific circumstances as possible. The solution can’t be simply to turn women’s refuges into gender-neutral ones, just as how trans women would be very poorly served by shelters which allow them access in theory (often just to fulfill legal requirements) but fail to accommodate their specific needs in practice. All of this tells us that this goes way, way beyond a simplistic analysis of “men vs women.”

It’s Not Male Victims, It’s The Men In Parliament

By making this a (cis) men vs women issue, we’re overlooking groups that are even more vulnerable to DV: ethnic minorities, trans women, women with no recourse to public funds, teenagers and so on. By making this a men vs women issue, we’re pitting victims against each other for a limited amount of resources instead of asking why they’re fighting for scraps in the first place. We need more women’s services and we need more men’s services, and we need more gender-neutral services. We need more services for queer people. We need more services for non-English-speaking folk and we need more services for refugees and asylum seekers. We need more services, period.

The problem is not, as MRAs argue, that DV is “wrongly” characterised as a “feminist issue.” It is one. The problem is that as a feminist issue, it gets pigeonholed as a minority interest and gets nowhere near the attention it deserves. But it’s even more than that: DV is so pervasive that abusers are literally lawmakers. This isn’t a matter of Labour vs Conservative ideologies — like many feminist issues, DV disrupts what we understand to be “public” and “private” affairs, making lawmakers of all political stripes deeply uncomfortable in legislating on it.

Increasing the visibility of male victims of DV is important, but casting this as an issue in which the interests of male and female victims are diametrically opposed to each other is glossing over the complexity of the problem of and the highly varied circumstances of its victims. Very importantly, it’s absolving the men at the top of the hierarchy from responsibility. We need to stop pointing fingers at each other, and to turn our attention upwards instead.

Feature image via Shutterstock