feature image via Shutterstock

Last winter, after a tumultuous year of soul-searching, I packed my bags and left New York City for the allegedly greener pastures of Los Angeles. I’d been dreaming of this move for ages, and I had a lot of friends and family out there, but I didn’t have practical things lined up like say, a job, or a car. I approached these issues with a combination of naiveté, east coast hustle and sneering bravado, reasoning that I’d probably just work harder/smarter/better than everyone and figure something out. Oh, this isn’t a walking city? I thought smugly. I can walk. I’ll walk all the fuck OVER this town!

I learned quickly that I was dead wrong. Not only is the city of Los Angeles gigantic, hilly and sprawling, its public transportation system is absolute garbage. It wasn’t long before a friend introduced me to ride-sharing apps like Uber and Lyft. Although I was skeptical at first, I was quickly won over by the convenience, cost-effectiveness and presumed safety of ride-sharing. On nights when I found myself stranded for 45 minutes or more for a bus that would never come, it was a relief to know that I had a reliable, relatively cheap option available to get myself home. Just a few short months later, I can’t say I would feel ethically comfortable ever using either of these services again.

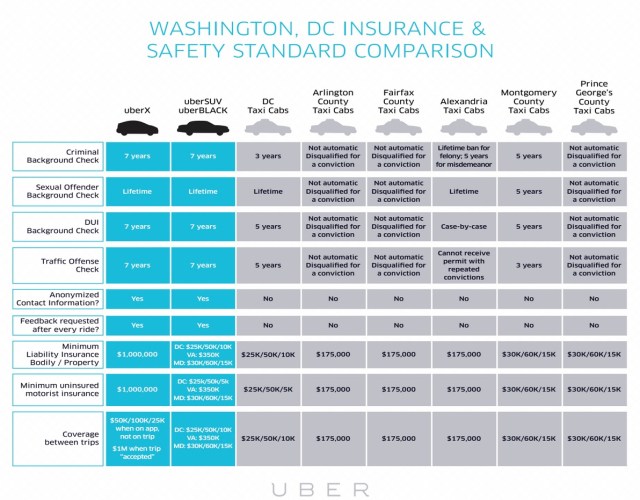

Although companies like Uber and Lyft offer some degree of accountability (both the driver and passenger are easily identifiable and therefore traceable), the media is rife with reports of the dangers of ride-sharing. Though all drivers are subject to background checks before being allowed to pick up passengers, it’s unclear how thoroughly they’re vetted. Despite comprehensive explanations like this guide to Washington, DC’s background check process, drivers with violent pasts have been known to slip through the cracks.

The media has widely reported multiple incidents of drivers raping, assaulting, stalking or even abducting passengers — in short, it seems that even though Lyft or Uber’s system by all accounts should be safer and more reliable than jumping into any random taxi that happens to be passing by, it isn’t. Both companies’ business structures ensure that they aren’t held accountable for the actions of individual drivers — drivers are hired as independent contractors (sometimes condescendingly referred to as “driver-partners”), and training rarely extends beyond a couple of 5-minute videos explaining how the app works. Concerns about accountability go beyond the driver-passenger dynamic; it’s been revealed that Uber corporate employees may be able to view information about passengers, including their up-to-the-minute location in Uber vehicles. Not surprisingly, Uber has been less than transparent about this feature.

After national news began covering an incident in which one driver attacked his passenger with a hammer, Uber began offering optional 4-hour training courses to drivers — at $40 to $65 expense per class. For many drivers who currently struggle to make even minimum wage under Uber’s current business model, this cost is prohibitive.

In most major cities in America, Uber and Lyft are absolutely destroying the local taxi companies, while remaining desperately at odds with one another — like Spy vs. Spy if one of the spies was wearing an awful pink mustache. In Los Angeles, where I spent several months as a Lyft driver, ride-sharing is much more convenient and less expensive than cabs, and it’s a welcome alternative in a city where parking is a nightmare and public transportation is unreliable or nonexistent. The benefits are obvious — DUIs are noticeably down in cities where ridership is up, and clicking a button on your phone to reserve a ride is way easier than fighting through a crowd of drunks to battle over a passing taxi. As Uber and Lyft engage in cutthroat price-gauging to better compete against one another, fares have become much more affordable and ride-sharing has become a realistic possibility to passengers in lower income brackets. All of this sounds great, unless you’re the driver.

Both Lyft and Uber make a lot of promises when they hire drivers. They’re very daring in their recruitment efforts, even offering several-hundred-dollar rewards for drivers who switch from Lyft to Uber (the nasty competition between the two companies is well-documented), as part of a marketing program called Operation SLOG (Supplying Long-Term Operations Growth). Drivers are promised a flexible, casual, easy gig with endless opportunities to make piles of money. Absurdly optimistic hourly rates aside, Uber actually offers to help new drivers finance brand new vehicles if they don’t already own one. This is where things get a bit tricky — Uber doesn’t actually finance the loans themselves, and many of their applicants have subpar or even no credit. Additionally, the nature of their pay system makes it actually impossible to predict drivers’ future earnings (Uber have bragged that drivers in New York average $90,766/year; this has proven to be nowhere near the case). Valleywag did a great job breaking down Uber’s sketchy subprime lending system, declaring that “…with cash flows demonstrably unreliable and civil investigations around the corner, Uber wouldn’t suffer from adding some more asterisks to its emails.” Uber aren’t alone in screwing over their “partners” this way — Lyft drivers who purchased $34,000 tricked-out SUVs after being promised increased revenue as part of Lyft’s brand new Lyft Plus program (designed to compete with Uber SUV) were left hanging when the program didn’t take off, and the drivers could no longer afford the 14 mpg gas guzzlers.

I became a Lyft driver this past summer, reasoning that it was a great way to earn a few extra bucks, learn the city and meet new people. After months of mostly fruitless job-hunting in LA, I was thrilled by how quick the background check process was and how enthusiastic and eager Lyft seemed to be about getting me out onto the road. I was matched with a mentor, who met with me and another potential driver in a McDonalds parking lot, and at no point asked me to get behind the wheel and drive him anywhere (which I later learned was the entire point of the mentoring session). This intrepid gentleman made a cool $70 ($35 per mentoring session) from the half hour he spent taking cell phone pictures of our cars and teaching us how to fist-bump passengers (Lyft drivers are more or less obligated to fist-bump passengers, in an effort to show how cool and personable Lyft is. It always seemed really awkward so I never did it, sorry.). After my mentor reported back to Lyft that I was a real human being who owned a real car, I was free to start picking up passengers, so I did so immediately. I quickly learned that I made the most money driving at night, and often hung around West Hollywood, mostly delivering intoxicated older gay men home from bars. Passengers always asked me how I liked driving and I always told them I loved it, that the whole experience of picking up total strangers in my car was a very unique and surprisingly pleasant way to meet people. My ratings were excellent.

Under Lyft’s current system, drivers have no way of knowing how much a ride costs until the next morning, when we’d receive an email reporting our earnings from the night before. An average ride was maybe a mile or so, and after Lyft collected their dollar safety fee and their 20% cut, I’d come away with about $3.20 per ride. Nobody ever tipped, mostly because the mythology behind ride-sharing is that the tip is included and you absolutely don’t have to — or even shouldn’t. I reasoned that I was still learning how the system worked, so it didn’t really bother me that I wasn’t making nearly as much money as they’d promised right away.

After a couple of weeks of Lyfting, I learned some uncomfortable truths about the whole process. First, it was just about impossible to make any money. Drivers walk away with 80% of the fare, with zero base pay – so if you don’t have any passengers, you’re just wasting time. The parent company keep the other 20%, and since they are constantly hiring new drivers, there’s a steady stream of income even if they offer a summer sale or other excuse for a discounted fare. At the same time, there were so many drivers on the road at any given time in any given area, it became tougher and tougher to actually catch a fare – and with prices at an all-time low, there was even less money to go around. Lyft passengers are automatically paired with the closest available driver, and oftentimes that came down to circumstance, ie driving past a person at the exact second they requested a ride. On a typical Saturday night, there could be twenty cars hovering around one corner, hoping to catch a single person walking out of one bar. I never came anywhere near the $35 an hour Lyft’s website boasted I would soon be making. One night, I drove for five hours and made less than seven dollars before giving up and drowning my sorrows in pizza on the couch.

Another thing that bothered me about driving was passengers’ overall attitude towards the system. As a New Yorker, I’d never really thought about how I treated drivers when I took a taxi; I was always reasonably polite and tipped generously, but usually just talked to my friends or played on my phone. Now, I noticed how uncomfortable the dynamic could be, how rarely my passengers treated me as though I were an actual human being. I was regularly casually insulted or talked through, and although I joke about it often, I was very surprised to learn how awkward it was to have complete strangers making out furiously in the back of your own car (I spent that entire ride silently repenting for my drunken twenties). On several occasions, passengers literally thanked me for being an English-speaking white woman (seriously?!), and rudely asked me what my real job was. In Los Angeles, a lot of drivers are struggling actors who pick up shifts for extra cash, but a lot of us just needed to pay our rent by any means necessary — I was having enough trouble reconciling my current situation with my career goals, and one time when a passenger asked me that, I actually cried.

Lyft emailed me often, telling me that I was in their top percentage of drivers, that I was suddenly (within a month or so) qualified to become a mentor, that I was eligible for any number of perks. I began to wonder if everyone who drove for them received the same emails, and I was never assigned a single mentoring session. I wasn’t earning enough money to cover the amount of gas I burned through in a week (even in my earth-friendly Prius!), and found my enthusiasm for the gig waning swiftly.

My passengers asked me often how safe I felt as a female Lyft driver, and in an effort to keep the conversation light and pleasant (which I hoped would result in higher ratings), I lied through my teeth and told them everything was fine – that the nature of ride-sharing was so awkward and strange that people were often very pleasant and polite, and that I’d made a lot of great friends this way. I told them about how the drivers rate the passengers the same way the passengers rate the drivers, so I always knew what I was getting into and never felt like I was in danger. Truthfully, I worried about my own safety more often than not, and because it was so hard to catch a fare to begin with, I never turned down a ride no matter how inconvenient the location was, how low the passenger’s rating was or how uncomfortable the passenger made me. I simply wasn’t making enough money to be choosy, and declining or missing rides impeded my ability to earn percentage bonuses for hours spent in driver mode (Our acceptance rate had to be 90% or higher to collect bonuses, and every little bit helped). Before I signed up with Lyft, a female Uber driver had showed me all the places she’d hidden pepper spray around her car just in case she found herself assaulted. I thought spraying pepper spray inside a small vehicle sounded like a terrible idea, but I did wonder often what I’d do in that position. On only two occasions, I did have to cancel a ride due to concerns over my own safety or the safety of my car, and in both cases I was extremely lucky that the passengers in question exited my vehicle without a struggle.

So far, the only mainstream attention female drivers have received are glowing reports of how women are breaking into an often male-dominated industry and how convenient the flexible schedule is for working moms, but there have been surprisingly few inquiries into how Lyft and Uber are protecting the women who work for them. When a creepy male passenger once refused to give me his address for my GPS and instead insisted on intermittently barking vague directions, I found myself actually wondering if he was taking me somewhere to hurt me, and if I would have to wait until the next day to email customer service to report it. There was no infrastructure in place to protect me should a passenger become violent, and I cringed as I imagined the form email I might receive in response — “Your feedback about your customer support interaction is important to help us improve your experience in the future.”

If the public were searching for clues regarding how these companies feel about the women who work for them, Uber gave the world a remarkable hint when it rolled out a daring new promotion in conjunction with an app called “Avions de Chasse.” Through their partnership with Uber, riders in Lyon, France could be paired exclusively with hot female drivers for a special ride with a twenty-minute time limit – with the tagline “Who said women don’t know how to drive?” As the English version of the app’s website explains, “‘Avions de chasse’ is the French term for ‘fighter jets,’ but also the colloquial term to designate an incredibly hot chick. Lucky you! the world’s most beautiful ‘Avions’ are waiting for you on this app. Seat back, relax and let them take you on cloud 9!” It’s unclear what exactly the Avions de Chasse app is actually for, but for unaffiliated women who are regular drivers for Uber, the implication that their job involves being an object for the male gaze is troubling.

Uber CEO Travis Kalanick smugly jokes that his extremely profitable company has garnered him so much tail that he now refers to it as “Boob-er,” so nobody exactly expected Uber to be particularly sensitive towards women. All the same, the whole Avions de Chasse catastrophe really takes the cake. As soon as BuzzFeed News got ahold of the story, Uber quietly pulled the promotion from their website, and later described it as a “clear misjudgment.” Avions’ co-founder Pierre Garonnaire described the situation as a cultural misunderstanding, explaining that “They didn’t anticipate the reaction of Uber US. In the US, you are more Puritan. For me and most of the people of France, it was a good [idea]. It was fun.” Sarah Lacy hit the nail on the head when she explained in her op-ed “The Horrific Trickle-Down Of Asshole Culture: Why I’ve Just Deleted Uber From My Phone” that Uber “…posted an ad that encouraged, played on, and celebrated treating women who may choose to drive cars to make extra money like hookers.”

Of course, Sarah Lacy’s critiques of Uber made headlines earlier this week when news broke that their senior vice president of business had openly discussed hiring a personal attack squad of investigative journalists to dig up dirt on Lacy — and any other reporter who dared speak ill of the company. Although Uber’s CEO has denied that such smear tactics are being used, there have been zero repercussions for the employee who made these very public, very specific threats.

When I received a company-wide email from Lyft informing me that they were about to start counting driver-initiated cancellations against our acceptance rates, I decided I’d had enough of driving and quit. The ability to cancel a ride if I felt unsafe was a flimsy but still important part of feeling protected, and now I couldn’t do so without jeopardizing my ability to earn bonuses or even remain an active driver.

The structure of both Lyft and Uber is designed solely to benefit the companies themselves, with little consideration for its “driver-partners,” or (in many cases) even for its customers. Neither company takes full responsibility for its worker bees, branding themselves as a technology platform as opposed to a transportation company. In theory, the idea of ride-sharing still sounds appealing and filled with enormous potential, but in actual practice, the system is mostly frustrating, unethical and honestly just not safe enough — for passengers or drivers.