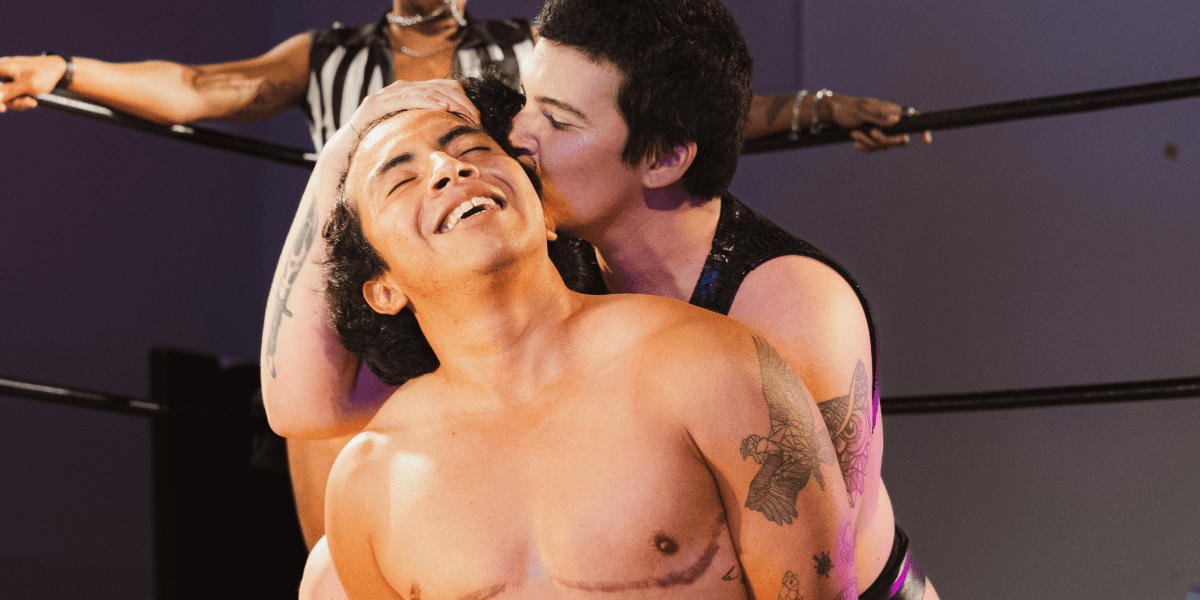

feature image via la flama

The term Latinxs began popping up on my tumblr feed about a year ago. At first, I ignored it. The onslaught of new queer terminology while necessary, radical and exciting, often exhausts me. It’s like, I know I have to learn about and embrace this new thing to keep up with my people but I just picked up five new terms last week. Can I get a moment to breathe?

But that’s just me and my cis-privilege keeping me from embracing things that don’t apply to my identity, know what I’m saying?

And, Latinxs didn’t go away. I saw it being used by more Afro-Latina/Latina centric, queer-ish blogs that I love. It’s staying power and something about that X made me want to learn more about it.

Where did it come from? What does it mean? Can Spanish be gender-neutral? What would my grandma think of a gender-neutral term for Latinos?

The more I read about it, the more sense it made and I felt that pride in my people. Like, way to push the boundaries of a language in order to place yourself and your needs at the center. Put that X in there and let them know you exist. Use that X as a beacon for all those who identify and feel similary. Here we are. You are not alone, you know?

As much as I read about Latinxs, I couldn’t fully grasp how to explain its usage to others or the importance of it, until this response piece from the news site, Latino Rebels. The Case FOR ‘Latinx’: Why Intersectionality Is Not a Choice written by María R. Scharrón-del Río and Alan A. Aja offers a fierce take down of a piece published by The Phoenix, Swarthmore’s indie newspaper. Their piece is literally “An Argument Against the Use of The Term ‘Latinx, which includes such gems as:

- It excludes any older Spanish speakers who have been speaking Spanish for more than 40 years and would struggle to adapt to such a radical change.

- If you take the gender out of every word, you are no longer speaking Spanish.

The Latino Rebels piece “The Case FOR ‘Latinx’: Why Intersectionality Is Not a Choice” dissects major flaws in the Swarthmore authors arguments which include the inability to comprehend the need for gender-neutral language, among other things.

Highlights from the Latino Rebels piece made me raise my brown fist to the sky, like yes, let’s do this and have these conversations! Why not queer up/reclaim the Spanish language?

- “…indigenous languages in Latin America (and throughout the world) range from the genderless to the multigendered, going beyond the binary. This is another instance in which Guerra and Orbea, while claiming to denounce imperialism, actually fall into one of the markers of colonization: the erasure of indigenous history and its cultural legacy.”

- “To change the Spanish language to include others is deemed as a threat to the whole Latinx culture and their identities. This is certainly another symptom of unexamined privilege and internalized colonization. Moreover, it also implies that our Latinx identity is so frail that without protecting the integrity of the language of our colonizers, we risk losing the main instrument of colonization that still binds many of us.”

But before I give away too much of the good, stuff, go read the article. Let the Latino Rebels know what you think and of course, as always, drop your thoughts in the comments here too.

What do you think of the term Latinxs? Do you use it? Did the Latino Rebels do right by the term in their argument?

Here is that link again:

* The Case FOR ‘Latinx’: Why Intersectionality Is Not a Choice

Comments

A genderqueer friend of mine in Central America who uses -x endings (instead of -a or -o) started using them when talking about and to me, and it is among the most important, kind and revolutionary experiences I have ever had. As a white gringx who had been living in Latin America, I don’t know if I ever would have taken for myself the right to transgress and queer Spanish in that way, but to have it given to me freely by someone who also uses that language brought healing and light to my whole experience with language and gender and self.

This is also to say: Latin American queers are absolutely embracing and transforming the x as one way to make themselves a home in their language. Fuck The Phoenix’s shitty Google results.

I am really jazzed to see this article on Autostraddle.

like how dare anyone assume that an entire group of people from all sorts of very different countries feel one type of a way about a word?

and i didn’t do much researching on the writers at swarthmore but i wonder if they’re queer and have ever had to reclaim language, you know?

cuz if not, how could they even begin to understand the crushing self-exploration one has to overcome in order to do such a thing and make space for oneself within a language that was used to conquer your people?

Yes! También like, people are also mad that queers are fucking with English, but that hasn’t stopped us. The Swarthmore article tries to talk like the U.S. latinxs who are crafting, sharing and using this language are somehow trying to imperialize Spanish and it’s absurd and horrifying.

I’m a native spanish speaker (I was born in Argentina) but I have very limited contact with native speakers, and zero contact with queer native speakers. I had been wondering for a while how removing gender from spanish would work.

What does it sound like?

It cracks me up that the arguement against it is: it’s hard for old people to catch up…well yeah…that’s kind of the point right?

The latinxs I know (mostly Central Americans) mostly use an -eh sound (e.g. elle, guape, cansade). I’ve also heard -oo and -au pronounciations. But it’s a very nascent thing that hasn’t spread much beyond queer and academic spaces (at least in my limited experience!)

Muchas gracias, @audreyfaye and @ogfunkbandit. I first encountered “queridxs”, “todxs”, and “Latinx” after starting grad school a couple of years ago (in a Department of Spanish and Portuguese). Once I found out what it was, it started to grow on me, but with the giant caveat that I had no idea how to pronounce it. I don’t really notice any particular difference in how people in my department who use the x when writing to mixed-gender groups (todxs) pronounce things when speaking (todos?), and was resigning myself to a written but unpronounceable revolution. In English, most people I’ve come across pronounce it “latin-x”.

Despite the pronunciation uncertainties, the x has grown on me. My best friend from elementary school, and probably life, came out as genderqueer, and later agender, around the same time that I started to tiptoe out myself as a tortillera. Or something.

We can twist our sentences around in the attempt to avoid gendered adjectives and pronouns, but we can’t go through life locking up our tongue just to avoid gendered language. Spanish does not just belong to the Real Academia Española. Lately I’ve started to feel surprisingly comforted when classmates (and one of my professors) address their emails to “queridxs” or “estimadxs estudiantes” – surprised, that is, because I didn’t expect that one little radical fissure in the edifice of gendered language would come to mean much to me personally, especially so quickly. Yesterday one of my best students began his email “Querido Profesora”, and though I corrected it to “Querida”, I almost liked it better his way.

This all leaves me torn, though, when it comes time to teach introductory or intermediate Spanish language classes to students who still make loads of concordancia errors. I mentioned “latinxs”, “latin@s“, and “xicanisma” briefly one day, but don’t currently dare use more than the @ in class. In part, I think I oughtn’t complicate things more for them, since goodness knows there are already plenty of grammar concepts that they don’t know well. Then I think that I should complicate things for them, so that the burden of gendered language is not borne only by those it does not fit properly. Certainly if/when I get to teach literature courses (and can trust that they have a reasonable grasp of concordancia), I’d like to use the x when writing to my students. Currently I just try to avoid gendered words for my students as a whole (“Hola clase” or “buenas tardes” instead of “queridos estudiantes”), but it’s hard.

En efecto, this is something I’ve been thinking about a lot lately, so it was great to see this piece today. What do you all think regarding the language classroom and the use of x?

I’m not Latinx, but I’ve heard it as both -ex (like ex-girlfriend) and -ix (like fix). I personally think the -ex sounds more in place with the rest of Spanish pronunciation.

I’m from Spain, native Spanish speaker, and we use both -x(s) and -e(s) as endings for neutral adjectives, pronouns and names; we usually pronounce them as -e(s).

:)

Is it all right if I ask how to pronounce latinx? Is it la-tinx, like Thinx? or lateen-ex?

See the comment under Beatriz’s for pronunciation! I was wondering this too

Thanks, but I think @audreyfaye was talking about what other, gendered words sound like when the gender is removed…

@queergirl Actually I was speaking generally! The Latinx queers I know in Latin America that use -x endings use them as a written code and use other solutions for pronunciation. So, Latinx would be Latin-e out loud. Not sure what primarily-English speakers do though, as far as pronunciation.

Ohh ok, awesome. Thank you so much for answering!

YESYESYES. Also, it is absolutely a part of linguistics that language influences culture (Sapir-Whorf hypothesis)…. AND vice versa – language is totally subject to change based on cultural influence! Languages have always changed over time, they’re NOT written in stone and unchangeable (as so many people would like to think). So F that noise about excluding older speakers – total straw man argument.

Loved this! Sharing it and bookmarking it as a resource.

This is probably completely unrelated, but since I can only comment as a Brazilian person, by this standard Brazil and Brazilian people are not Latin(x), right? I don’t personally identify myself as latina for a number of reasons, but I’ve known Brazilians who do and especially Americans who do, and the article places a lot of emphasis on Spanish language, so I’m wondering where you stand on that.

Yeah, this is an important point. I’ve had a lot of Brazilian students who identified as latino. That’s one of the reasons the term Hispanic is usually rejected.

Technically, we all are latins, because the term it’s a reference to the root of our languages, a root that Spanish, Portuguese, French, Italian and several more share: Romance languages, languages that evolved from Latin.

I’m from Argentina and I want to apologized in the name of all my fellow argentinians because that time of the year is coming: summer vacations, that time of the year when we express our need to butcher your language. I’m really, truly sorry, honestly.

It’s ok Freakazoid, we butcher yours too when we go to Bariloche in the winter

I don’t really agree with the argument of the origins of the term. If you go by that, Spanish, Portuguese, French and even Italian people are Latin too. Just because that’s its origin it doesn’t mean much nowadays, from my point of view. And I don’t really think Brazil is culturally similar enough to be grouped with ex-Spanish colonies on the continent; on the contrary, I feel like it’s reductive of Brazilian culture and all its particularities and history, which doesn’t have anything to do with ex-Spanish colonies. Everytime someone assumes we speak Spanish because ‘we’re all Latin’ it makes my skin crawl. I just don’t think the association is valid, and the only reason I can come up for the insistence of it is racism similar to calling Africa a country. And here it doesn’t even have the bad excuse of similar skin colour.

I was gonna mention Bariloche as well but Carmen beat me to it haha. I don’t imagine our portunhol is very flattering either.

I’m Brazilian and I don’t personally identify myself as latina but whenever that comes up pretty much all of the Americans around me insist I am Latina so I just agree with them to make them shut up.

Well, times are changing. I lived in the US for 2 years and I still remember those days when I was “Mexican”.

Love this. AND I learned about/started using the -x in Central America. And my first reaction was nothing short of a sigh of relief. A deep breath. It was a reclamation of a space…similar to the feeling I get when I find bathrooms are non-gender specific. It’s “Gracias a la vida. Voy a orinar en paz.” Small victories that feel infinitely huge.

Learning, making mistakes, asking questions. That is part of the process. Language is not static…it’s alive. It evolves as culture and humanity evolves and grows. This idea and subsequent “-x” movement stems from folks who identified the need for space, recognition, and inclusion. So who is to question or invalidate that inherent need/liberation to a group of people/luchadorxs.

“Learning, making mistakes, asking questions. That is part of the process. Language is not static…it’s alive. It evolves as culture and humanity evolves and grows. ”

i love this. i feel like queer culture moves in the world this way, always aware that we’re part of the beauty and chaos of the whole fucking universe. so why should we give any fucks about following the rules of language? we are language.

Boom. Drop the mic. we are fucking language.

Many thanks for writing about María and Alan’s essay! Incredibly kind of you.

any time, i listened to the podcast last night too. i would love to speak with them further on this topic.

I can’t talk for latinxs as I’m a white Brazilian cis woman (who doesn’t identify as latina) and I don’t think that’s my place, but in Brazil there’s also a lot of discussion regarding the use of “x” instead of “o”/”a” to make language more gender-neutral, and I tend to prefer to find neutrality in different ways (which doesn’t mean I don’t use the x when it’s preferred by those I’m speaking to, of course). There’s a very interesting essay highlighting why (written by a Brazilian gender-nonconforming person), but it’s in Portuguese so I don’t know if it will be accessible to most of the Autostraddle readers (I think it might be for those who read Spanish, at least): https://naobinario.wordpress.com/2014/11/01/deixando-o-x-para-tras-na-linguagem-neutra-de-genero/ The main reasons mentioned in the article (& the ones I consider most relevant) are regarding the fact that the “x” can’t be properly pronounced in Portuguese; therefore, it changes written language but can’t be adapted to spoken language, and it’s also limiting to people who depend on screen readers to read on the internet. The writer recommends finding neutrality in sentence structure, not on a word level, but I’m having a hard time giving good examples in English (which is more of a gender-neutral language than Portuguese or Spanish). Anyway, I just thought it might be interesting to provide a perspective that I didn’t see in the articles – one that’s for gender-neutral language, but through different mechanisms.

(However, I’m not against the use of the x, and I’m all for changing language to be more inclusive of all different identities! I just think that’s an interesting subject, loved the Latino Rebels piece, and thought this might add to the conversation)

Very good pounts

I thought of this article too! After reading it I’ve mostly been using ‘person’ if I don’t know their gender, suppressing articles etc (like the writer outlined) or even if the person I’m talking to speaks English we switch (which is a bit troublesome but less uncomfortable than assuming or assigning). I haven’t met someone who really preferred using the ‘x’ but I’m not at all opposed to it, especially if the other person prefers it, though I do think the language should eventually evolve for a more accessible solution (i.e. one that can be used both in written as in spoken language).

miss_sofia,

Thank you for the essay article link! I used Google Translate for (rough) translation, and found it very comprehensive and informative even at my limited understanding of Spanish and grammatical gender. I will definitely be referring back to it as I continue to learn Spanish and explore the applications to English as well.

So as a british person who learned german at school, this is all quite alien to me. Am I right in thinking the x is used for adjectives as well as nouns? Is spanish one of those gendered languages that if it wants to call me tall it has to add a gendered suffix to the word tall? I’ve seen the word latinx written down but I thought it just meant ‘latino or latina’ and didn’t go any further.

Yes, spanish works like that, there are gendered suffixes added to adjectives. So, for example, tall would traditionally be alta (for a woman) or alto (for a man). (Or I might be using the wrong word because I’m a little rusty on my spanish and it’s similar enough to my native portuguese for me to confuse words sometimes, but that’s the gist of it.)

Ahh thank you! I think its really interesting the way that language shapes our view of the world. In a simple way, colours are just arbitrary definitions that we use to classify objects that actually exist on a spectrum. Start applying that to ways in which we classify ourselves, and I am really interested!

We also use what we call grammatical articles (“la” for a woman, “el” for a man, in the singular case.) when we need to specified gender into a neutral word, for example “la Presidente” (woman), “el Presidente” (man).

I love this, as someone who lives in south america, is latinx and frequently uses this term, this article makes me really happy, because latinxs is getting out here. And here it’s actually used a lot more than latina o latino, at least in Valparaiso where I live.

The x is usually added to most words to refer to any person/human, it’s actually been used in legal documents for many years.

Gender has been my #1 frustration with my own language, French, since I had my queer awakening (and also Spanish and Italian, which I’m learning). It physically pains me every time I have to refer to my best friend with feminine words in every language I can sort of communicate in except English. I’m really glad Latinxs found a simple way to adapt their language, and I hope the rest of us catch up soon.

Me encanta esta palabra! Voy a empezar a usarla para ser mas inclusiva :)

Also, this quote is just PERFECT: “it also implies that our Latinx identity is so frail that without protecting the integrity of the language of our colonizers, we risk losing the main instrument of colonization that still binds many of us.” I am proud to be a Spanish-speaking Latina (I use the “a” ending to describe myself because I’m a cis woman). In my work with migrants from Central America, I’ve met a few who spoke little to no Spanish. They spoke indigenous Mayan languages such as Mam, K’iche, Popti, Chuj, and Qanjobal. I don’t know anything about the linguistics of those languages, but I’m glad that someone brought up the point that Spanish is not the main, unifying marker of Latinx identity.

i know how it is to have a native language which necessitates a rewrite of the entire grammar to merely avoid saying total dicktastic rubbish that makes you feel like washing your mouth with bleach after. The most impressive part is not the actual rewrite though – it’s when you meet someone who independently has rewritten it to the exact same, predominantly passive voice, structure.

Even if it is a thing of youth/nymphness and as a full adult/imago you have no use for it – still singlehandedly butchering an entire shared system of concepts and signals is something that makes you feel warm inside, in a hacker way.

Interesting to read so many positive responses to latinx. I get the impression that it is not really a thing outside of the USA/Canada, and that it is yes considered American Imperialism, which that Latino Rebels article didn’t really address properly. I mean, if anyone is using indigenous groups affected by Spanish colonisation to make a point arguing for the English colonisation of Spanish, that is pretty messed up. It sounds like, “well, you colonised someone else!” finger-pointing without actually doing any heavy lifting for the indigenous groups affected by Spanish colonisation. They acknowledge that there are indigenous languages that are multi-gendered, so why not actually discuss with someone who speaks Spanish as well as, say, Otomi to find a possible solution that does not default to the English pattern of de-gendering? Why not dismantle the colonising language rather than pile another coloniser on top of it?

A proper example highlighting how cumbersome gender-neutral consistency would be beyond simply the label latinx is: “mi amigx divertidx esta dormidx porque estaba cansadx” — very different from the terrible example given in the original “against” article. If you want to bring up the colonisation of indigenous groups for the sake of this argument, just imagine someone whose first language is Otomi and their second is Spanish having to learn these very English conventions on top of the two languages they already know.

As an outsider, I originally thought latinx was a really cool idea, but these are the arguments I’ve heard against it and I’d love to hear those be addressed properly.

Well, as some other commenters have mentioned here, it’s not something that’s just happening in the US and Canada. @audreyfaye discussed their experiences in Latin-America, @tosca mentioned their experiences in Chile, and I have friends back home in Puerto Rico who are using it and know it too, for example.

Also, I think that it’s super valid to have cultural change coming from Latinx communities within the U.S. too because they are not “lesser” Latinx beings than those currently residing or directly born in Latin-American countries. There’s definitely an element of US/citizenship/imperialism questions there, but I also want to push against the idea that just because U.S.-based Latinx are promoting a shift, it’s bad or imperialistic. Like whatever, Spanish itself is a colonizer tongue in the first place, y’know?

I don’t think we need to de-gender objects (like “el guineo” and “la pelota”) or whatever, but honestly, “mi amigx divertidx esta dormidx porque estaba cansadx” isn’t that hard to read aloud once you understand how to pronounce the X in the first place. It’s just one sound, regardless of if you do the “-e” ending or the “-ex” ending. It feels weird to most people because it’s new, but familiarity and practice would fix that in a pinch. There are some ways we still need to figure out how to deal with gender neutrality (e.g. el presidente vs. la presidenta vs. ???) but there are folks theorizing about it already though it’s not super widespread (e.g. le presidentex, or just using la presidentex, el presidentex, l@ presidentex).

People who try to learn Spanish or learn another language will always have to content with the fluid nature of words and shifting linguistic systems. Languages don’t exactly or easily fit within each other’s frameworks. There’s no “ñ” in English. There’s a personal infinitive in Portuguese, but not in most other languages, even Spanish. The list goes on.

I’m a little confused about people saying gender-neutralizing Spanish is imposing English grammar on it, though? Like…English is not the only gender-neutral language? And regardless, gender-neutralizing is coming from a place of wanting to make space for gender-variance and unmark gender in certain ways rather than a desire to impose English on anything? The x is a letter in both languages, and it’s not changing grammar, just spelling… But maybe I’m misreading the question or something.

I really like the idea of gender neutral terms and gender neutrality. Romance (as in Rome not eros) languages have always struck me as harsh. 1 man in the group of 100 women it’s no longer nosotras, but nosotros.

Nevermind in some dialects nosotras didn’t exist.

But how is the “x” going to get pronounced? Or is it just going to a written thing?

What about gender of non-person nouns?

Not hating just thinking, like I do about galaxies they may contain life non dependent on photosynthesis, or oxygen and hydrogen.

Language is living thing and living things exhibit change, which is not exactly a Gloria Anzaldúa quote but it feels close enough not giving some acknowledgement feels steal-y and everyone should read her work.

@gunna-see-the-light, I commented above in response to another person :) I also was featured in the recent genderqueer roundtable and my contribution was literally all about this whole Latinx business, XD.

Just to add to the discussion regarding Brazil, in terms of international politics, the brazilian government actually distinguishes Latin America from South America. They are separated groups, not something that can be considered one single entity. There have been attemps to treat Latin America as one at certain points, but they have all failed. I think this influences the way brazilians identify themselves. The government itself has been known to see Latin America as distant countries geographically, politically and culturally. This distance is spread in schools too, and it can bring that idea of, uh, if we speak portuguese and we’re not in the middle part if the continent, then we’re not latinas/latinos/latinx at all. In fact, a bunch of brazilians don’t even see people from Argentina/Chile/Colombia/Uruguay/etc as such.

Also, would people from the Guiana be considered Latinx too? Because they’re French, they’re part of the EU, their currency is the euro, they speak french… and they’re in south america basically. Anyone want to adventure on a theory here?