Since the nationwide “Don’t Say Gay” bill passed in June, you can be arrested in Russia for telling a minor that gay people exist, being part of a public LGBT assembly, or for “socially equating traditional and non-traditional sexual relationships.” The new laws are both wide-reaching and scarily vague, and serve to legitimize and institutionalize an existing national attitude towards gay people that positions them as, at best, second-class citizens and, at worst, subhuman (State Broadcasting Director Dmitri Kisilev recently appeared on Russia’s most popular news program saying that gay people’s hearts should be deemed unfit for transplants, to wild applause). Gay parents who can manage it are fleeing the country lest their children be taken away. LGBT teenagers are being abducted and abused by anti-gay extremists, with no reponse from authorities. The rules also apply to foreign tourists, as four Dutch filmmakers found out when they were recently detained and questioned by police.

Interesting timing, considering that Russia is in for a giant influx of foreign tourists in about six months, along with a searing dose of international spotlight. On August 1st, Russian Sports Minister Vitaly Mutko told a state news agency that anyone advocating a “nontraditional sexual orientation” at the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics will be “held accountable… Even if he’s a sportsman, when he comes to a country, he should respect its laws.” Legislator Vitaly Milonov told the BBC that the Russian government lacks the authority to suspend the laws even if they wanted to. A week later, Mutko, apparently training for the Strategic Backpedaling event, asked the law’s critics to “calm down” and assured everyone that as long as LGBT athletes and spectators keep quiet, everything will be fine, because Russia’s constitution guarantees “rights for the private life and privacy.”

But promising not to engage in an all-out witch hunt is not the same as actually guaranteeing anyone’s right to self-expression or an honest existence. And even if Olympic participans and visitors are totally safe, these laws will go on making life miserable for millions of Russian citizens long after the stadium is empty. Back in February, Kristen took the LGBT athletic community’s pulse regarding Sochi after a Russian judge pre-emptively banned the Olympic Village Pride House. Now that these laws have passed, the trepidation expressed by these out athletes is finally spreading to the rest of the world. What should we — as individuals, committees, and nations — do about Sochi? What can we do, and what have we done before? Here’s a breakdown of a few options that have been presented, along with how they’ve worked in the past.

Boycott the games entirely

Actor and playwright Harvey Fierstein called for an all-out boycott in a recent New York Times op-ed, drawing a parallel to the 1936 Berlin games and saying that “there is a price for tolerating intolerance.” British comedian Stephen Fry echoed this in an open letter to the International Olympic Committee and British Prime Minister David Cameron:

“The IOC absolutely must take a firm stance on behalf of the shared humanity it is supposed to represent against the barbaric, fascist law that Putin has pushed through the Duma… Let us realise that in fact, sport is cultural. It does not exist in a bubble outside society or politics… An absolute ban on the Russian Winter Olympics of 2014 on Sochi is simply essential. Stage them elsewhere in Utah, Lillyhammer, anywhere you like. At all costs Putin cannot be seen to have the approval of the civilised world.”

The history of Olympic boycotts is long and various. Olympic historian David Wallechinsky considers the 1956 Melbourne Games to be the site of the first true boycotts, and they started out with a bang — seven different countries refused to participate for three different reasons. Subsequent withdrawals have followed in this spirit — they’ve been used to show dissatisfaction with host countries’ politics (as when Taiwan refused to participate in the 1976 Montreal Games when the Canadian government wouldn’t recognize them as part of the Republic of China), with the International Olympic Committee’s decisions (as when twenty-six African nations boycotted the 1976 Montreal Games after the IOC refused to ban New Zealand even though they had sent a rugby team to tour apartheid South Africa), and as a tit-for-tat (as when the Soviet Union boycotted the 1984 Los Angeles Games four years after the US stepped out of theirs). Spain even invented The People’s Olympiad in 1936 as a replacement for, and protest against, the Berlin games (although the Spanish Civil War broke out before they could go through with it).

The United States has boycotted only once, though we came close another time. In 1936, when Hitler was coming into power, there were intense discussions as to whether the US should stay out of the Berlin Games. In the end, Nazi sympathizers within the US Olympic Committee tipped the scales, and the US participated — a decision made, as Fierstein points out, to the retroactive regret of many. Forty-four years later, thanks to Jimmy Carter, the US convinced 62 other countries to join it in boycotting the 1980 Moscow Games, a decision now “universally reviled as Cold War posturing that accomplished nothing.” So it looks like we’re 0 for 2 in terms of boycott decisions.

Large-scale boycotts seem unlikely this year. President Obama told reporters Friday that, although “nobody’s more offended than me about some of the anti-gay and lesbian legislation that you’ve been seeing in Russia,” the US will not boycott the Games, pointing out that there are many countries we disagree with that we “do work with” anyway. He spoke more about this on The Tonight Show earlier this week. British Prime Minister David Cameron followed suit on Saturday, tweeting that he shares Fry’s “deep concern” but believes “we can better challenge prejudice as we attend” the games. Many experts and athletes agree, arguing that if countries boycott, discussion of whether or not they’ve “overreacted” would overshadow any message they were attempting to send, and that the athletes, rather than the Russian government, would suffer in the end.

What’s the attitude on the ground from Russia’s LGBT community, however? Last week, 23 Russian LGBT activists spoke out in support of a boycott, but in a recent article on Gay Star News, Anastasia Smirnova, general project manager for the Russian LGBT Network, urges allies not to boycott:

“We believe calls for the spectators to boycott Sochi, for the Olympians to retreat from competition, and for governments, companies and national Olympic committees to withdraw from the event risk to transform the powerful potential of the Games in a less powerful gesture that would prevent the rest of the world from joining LGBT people, their families and allies in Russia in solidarity and taking a firm stance against the disgraceful human rights record in this country.”

Ban Russia from participating

Some advocate for a reverse approach, calling on the International Olympic Committee to ban Russia from competing in their own games. Cyd Zeigler, co-founder of Outsports.com, argues that discrimination against any athletes directly contradicts the Olympic Charter:

“‘The practice of sport is a human right,’ the charter reads. ‘Every individual must have the possibility of practising sport, without discrimination of any kind and in the Olympic spirit’… That’s not just an isolated sentence in the midst of dozens of charter pages; it’s right up front, in the section called ‘Fundamental Principles of Olympism.’ …And the Russian law doesn’t just violate one word or one clause of the Olympic Charter; it violates the entire statement. The law doesn’t just punish Russian athletes; it subjects competitors from every nation to discrimination and flies in the face of the Olympic spirit.”

Zeigler argues that making Russia watch its own Games from the sidelines is the best way to ensure an impact that goes beyond one Olympics — both in Russia and internationally, as it will send a message to similarly homophobic countries that want to host major sporting events — and to involve the Russian populace (“instead of asking our athletes to carry messages that would fall on deaf Russian ears, it would drive Russian Olympic hopefuls to speak out to their own government”). He cites all sorts of past precedents to back himself up — South Africa was banned from competing from 1964 to 1992 because apartheid went against the Olympic spirit. Afghanistan was banned from the 2000 Sydney Games because of human rights abuses of women; after a call for similar bans of Qatar and Saudi Arabia, all three countries included women on their teams in 2012.

Although banning a country from their own Games is a more difficult endeavor, the IOC has pulled that off before, too — the 1920 Olympics were supposed to be held in Budapest, but because Hungary was a German ally during WWI, the IOC transferred them to Antwerp. George Takei and thousands of others have signed a petition asking the IOC to move the whole thing to Vancouver. However, judging by the IOC’s recent statements, which have consisted of “little beyond tardy and lukewarm criticism,” this seems vastly unlikely.

Let the media spread the word

If there’s going to be no official action, maybe we can at least count on Bob Costas. NBC paid $775 million for exclusive American broadcasting rights at the Sochi games. Human Rights Campaign President Chad Griffin recently wrote to the company’s CEO, pointing out that when he bought this privilege, he also purchased:

“a unique opportunity — and responsibility — to expose this inhumane and unjust law to the millions of American viewers who will turn in to watch the games… it wouldn’t be right to air the opening ceremonies, which is an hours-long advertisement for the host country, without acknowledging that a whole segment of the Russian population — not to mention foreign athletes and visitors — can be jailed for an immutable aspect of their identity.”

An LGBT rights group called Truth Wins Out did Griffin one better and started a petition asking NBC to make Rachel Maddow a “Special Human Rights Correspondent” during the Games. The National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association (NLGJA) also released a statement asking NBC to “include LGBT athletes in your coverage, and put into context the personal challenge attending the Winter Olympic Games presents for them,” as well as offering their combined expertise, perspective, and assistance.

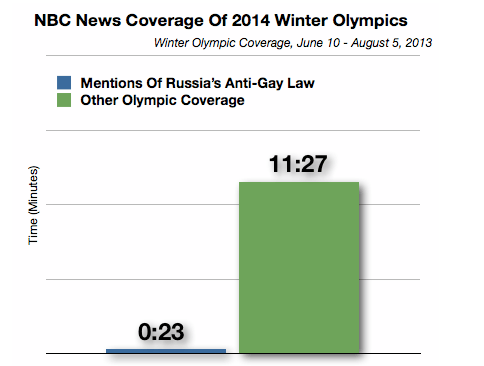

As of yet, NBC has failed to bite. Beyond promising their LGBT employees that they will do “everything possible to keep them safe” despite the laws, and making statements about how they “strongly support equal rights and the fair treatment of all people,” the broadcasting brass has been pretty vague about how they plan to deal with the human rights abuses occuring in the country they are, traditionally, supposed to be buttering up. NBC Sports Group chairman Mark Lazarus said that the laws will be addressed “if they impact any part of the Olympic Games.” This seems less like a promise to tackle the hard issues, and more like a plea to the Russian government to sweep anything under the rug that won’t look good over uplifting horn music, not unlike Sports Minister Mutko’s plea to the international media to “calm down.” A Media Matters report shows that, as of August 9th, NBC had devoted about 12 minutes of airtime to the upcoming Games, only 3% of which even mentioned the discriminatory legislation.

NBC’s track record at past games isn’t exactly gold either. They’ve held exclusive American broadcasting rights since 1996, and as scholar Cassandra Schwarz points out, “Olympic Games media coverage has become increasingly limited, allowing the IOC to have greater control over popular perceptions of the Games.” During the the 2000 Sydney Games, for example, “In hopes of downplaying Australia’s long and brutal history of racism towards Aboriginal peoples, the Olympics was promoted with an aim to package “Aboriginality” as a recognized and celebrated component of Australia’s “multiculturalism.” So rather than drawing international attention to humans rights abuses that were still occurring, the involvement of a marginalized people just helped legitimize the false and flattering image the Australian government wanted. (Obviously similar histories are swept under the rug every time the United States hosts the Olympics, regardless of television outlet.)

The IOC and major media outlets also came under fire during the 2008 Beijing Games for counting on the country to clean up its act before the games and for failing to address the degree to which it didn’t. Beijing itself was called out for silencing critics, giving only lip service to protesters, and blocking internet access. Russia is doing the same — reports by Human Rights Watch show that authorities have already “harassed and pursued criminal charges against journalists, apparently in retaliation for their legitimate reporting” on abuse of migrant workers, disappearing taxpayer money, and forcible eviction associated with the Games. Based on past experience, we can’t count on small news outlets to have the resources or clout necessary to properly chase these stories, and we can’t count on NBC to use its considerable influence to do it either.

When people talk about how the US dropped the ball in 1936, they often mention how there was hardly a contrary peep from US journalists, as they were taken in by Germany’s well-scrubbed facade. Let’s not let that happen again.

Organize official protests

In another New York Times editorial (the Gray Lady has good Olympic instincts), Frank Bruni imagined the US team staging a “not ostentatious,” “subtly recurring,” and “wordlessly mocking” rainbow flag parade during the opening ceremonies. He went so far as to suggest “something small stitched into the uniforms” to serve as a national visual statement.

Historian David Wallechinsky agrees that people should call the Russian government’s bluff, suggesting that athletes “smuggle banners into one of the stadiums” and asking “what are the Russian authorities going to do, arrest people right in the middle of the Olympics?” (And if they did, NBC would certainly have to report on it). Leading Russian LGBT activist Nikolai Alekseyev is organizing a Sochi Pride March to coincide with the opening ceremony (his earlier efforts to open a Sochi Pride House were shut down by the authorities). Alekseyev hopes that a march “will be much more effective [than a boycott] to draw attention to official homophobia in Russia all around the world and expose the hypocrisy of the International Olympic Committee.”

But there’s a problem with this idea. Rule 50 of the Olympic Charter expressly forbids “demonstration or political, religious or racial propaganda,” and since Russia’s law has overtly politicized LGBT identities, even an expression of solidarity now counts as a political demonstration. (This is why Tommie Smith and John Carlos were disqualified by the IOC following their iconic demonstration on the medal stand during the 1968 Mexico City Games.)

During the 2008 Beijing Olympics, IOC President Jacques Rogge lifted the all-out ban and allowed athletes to speak freely in interviews, even on Olympic grounds (but not in certain locations, including on the podium). Pro-Tibet protesters were able to briefly disrupt torch-passing ceremonies and unfurl banners in public places, but all were quickly detained. Olympic athletes, fearing IOC rules, loss of sponsorship, and accusations of bad sportsmanship, seem to think about organizing group protests more often than they actually do it. The athletic humanitarian organization Team Darfur considered large-scale demonstrations at the Beijing Olympics, but after their founder, Joey Cheek, had his visa yanked by Chinese authorities, they chose a subtler form of protest instead by asking former Sudanese “Lost Boy” Lopez Lomong to carry the US flag during the opening ceremonies. The German national team thought about wearing orange terry-cloth robes in solidarity with Tibet during the Beijing Olympics, but then decided the issue was “too complicated” to take a stand about. It remains to be seen whether the IOC will lighten the restrictions again this year, but it’s possible, especially as they’ve made several statements condemning the laws. Regardless, an organized protest, especially by a large group of athletes, would be a powerful way to get this issue into the news.

Count on individual athletes to take a stand

When Obama announced that the US would not be boycotting the Games, he added that he’s “really looking forward to… some gay and lesbian athletes bringing home the gold or silver or bronze, which I think would go a long way in rejecting the kind of attitudes we’re seeing there.” Nikolai Alekseyev would like to go even further, hoping that “all the sportsmen wear rainbow pins and talk about the issues during the press conferences” (former US Olympic diver Greg Louganis agrees, suggesting “a visible pin, an armband, [or] a bracelet”). Some individual athletes, including New Zealand speed skater Blake Skjellerup, have already pledged to wear some kind of solidarity symbol and to “be themselves” throughout the games.

There aren’t many examples of individual athletes protesting at the Olympics (beyond the statements occasionally inherent in being themselves and being awesome). At the 1908 London games, Irish-American shot-putter Ralph Rose refused to dip his flag to King Edward the VII, who hadn’t yet recognized Irish independence, during the opening ceremonies. The most famous example comes from Tommie Smith and John Carlos, the American sprinters who took home gold and bronze at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics and left the world with an indelibe image and no way to keep ignoring racial inequality in America. Smith and Carlos came to the podium “dressed to protest: wearing black socks and no shoes to symbolize African-American poverty, a black glove to express African-American strength and unity. (Smith also wore a scarf, and Carlos beads, in memory of lynching victims.) As the national anthem played and an international TV audience watched, each man bowed his head and raised a fist.” The silver medalist, Australian Peter Norman, wore an Olympic Project for Human Rights badge in solidarity.

Although they were banished by the IOC afterwards for breaking rule 50, and “returned home to a wave of opprobrium,” Carlos regrets nothing. “To be heard is greater than a boycott,” he told reporter Dave Zirin this year when asked to give advice to LGBT and ally athletes at Sochi. “If you stand for justice and equality, you have an obligation to find the biggest possible megaphone to let your feelings be known.” The Olympics are a globe-sized megaphone, and people at all levels will get a chance to wield it—leaders of nations, heads of committees, CEOs, reporters, coaches, athletes, fans. The whole world watches the Olympics. Let’s find a way to make sure they listen, too.

Comments

I have so many conflicting feelings about this. Having recently experienced living in a host city for the Vancouver 2010 Olympics, I’m really rather disenchanted by the whole Olympic spectacle.

However, years ago I was also recruited for the Canadian Olympic skeleton team (though I ended up staying in school instead), and these very games in 2014 would have been the games we were gunning for. I can’t imagine having spent the last 15 years of my life dedicated to a sport and then have all this come up.

I really feel for all the LGBT athletes. I hope they are safe and I hope they get to compete. Even if I have less than positive feelings about the IOC.

Looks like somebody needs to come out from under whichever rock they’ve being living under and get their priorities straight (snerk). Imagine if the whole event was boycotted or cancelled, what then? All those facilities going to waste.

After all, it’s just the winter olympics. There are so many other places with snow…like Siberia or Greenland with no a****y retentive politicians hung up on ‘nontraditional sexual orientations’. Besides,what kind of person invites people to their house for a barbeque and then tells people not to bring meat? A self-deafist dinosaurs that’s who. Those people need to wake up!Half of those athletes are probably LGBT anyway.Somebody needs to tune them before it’s too late.

And oh, FIRST!

You know ‘anal’ isn’t a swear word, right?

Oh, and, uh, NINTH! (or whatever.)

Ouch.

You do realize that Siberia is IN Russia…right…?

Not exactly. According to that online encyclopedia whose name begins with ‘w’ Siberia is a region that has been dominated by Russia since the 16th and 17th century. It doesn’t say they actually own it. Moving the winter olympics to Siberia would be like playing in Russia’s backyard after they kicked you out of their fancy house. It makes one wonder if all these laws being passed are effective in Siberia, if not then going to Siberia instead would teach Russia a lesson.

As for why I may appear to be walking on eggshells,it’s because of some flippant remark I made last week about burqas and trends which nearly got my goose cooked :D – Don’t bother looking it up because I deleted everything. It was too embarassing.Yes,more embarrasing than yelling FIRST when you’re actually second.

Sigh. I know its history, but that doesn’t negate the fact that politically, Siberia is under Russia’s jurisdiction. Also? How naive are you to think that Siberians wouldn’t care about non-traditional sexualities? Rural citizens are more likely to be staunchly conservative. Many of the horrific Neo-Nazi hate crimes have been committed in those rural regions, and the politicians are even more corrupt than those in the Kremlin.

Just to clarify, the Soviet Union boycotted the 1936 Berlin Olympics, but did participate in the alternative 1937 summer Spartakiad in Belgium… it was them who organized the alternative olympics, not Spain.

There are many reasons to opt out of this PR sham for Putin. My personal feelings are that if US athletes want to participate, go ahead and good luck. But I won’t watch the games, will boycott NBC and all corporate sponsors involved in the Sochi Games and will complain to any store selling merchandise promoting the games. Moreover, I would hope people from the US wouldn’t attend the games. It’s my hope that the US and EU bans the entry of any Russian politician or religious figure who’s involved in this witchhunt (and I would hope other countries ban our bigots as the UK has previously done).

Hey Gina, thanks for the correction! I didn’t realize the People’s Olympiad was part of the Spartakiad.

Thank you for this helpful post. I hope that many athletes do wear pins or make statements. Putin wants to use the games to show Russian prestige, so they should think twice before arresting foreigners (doesn’t guarantee they will, howver). But it would be really nice if the anti-gay laws spark serious international pressure on Russia’s many more serious human rights abuses against migrant workers, ordinary citizens who p1ss off local bosses, and anyone else who’s vulnerable. There have been a couple of cases of skinheads beheading Caucasians — torturing a gay teen is far from the worst of it.

All of the reported crimes are just making me sick to my stomach. And unfortunately one of the tortured teens did succumb to his injuries last week.

“[…] I hope that many athletes do wear pins or make statements […]”

Umm… they can get prosecuted for doing that…

I don’t think Russia can afford arresting masses of foreigners under the international spotlight. I’m all for calling their bluff.

Russia had no problem breaking down a gay pride event in Moscow and arresting people when Russia hosted the European Song Contest. To my memory the legendary chess person and activist Garry Kasparov was among those who got beaten up and arrested but I can’t seem to find any source that says the same, so it might have been another occasion, dude gets arrested and/or beaten up a lot. The last time during the Pussy Riot trial, when the wold was also watching. In short, Russia doesn’t seem to give a fuck about international spotlight.

I think that arresting Olympians would lead to a different sort of international spotlight than those other instances. I don’t know anything about the European Song Contest, but arresting another country’s Olympic athlete would cause a lot bigger diplomatic backlash than arresting/beating people for protesting a trial about free speech.

Also, arresting athletes that still have events would delegitimize the games and put an asterisk next to any medals won in the arrested athlete’s missed event.

That said, I think Olympians will only be safe from arrest if they do things like wear armbands, not if they organize/attend large scale protests.

You are right, Russia is probably going to be more tame with Olympians and I think, the athletes in fact can get away with wearing armbands or pins without consequences. But chances are, their armbands get cut of in the shot (or otherwise censored) when broadcasting for TV. In addition Russia also could forbid pride flags in auditoriums (which really happened during an European Song Contest – not in Russia though).

Censorship is always a problem in Russia anyway, but Sochi is Putin’s pet project, so he is not gonna let anybody rain on his parade. Literally – he is probably going to give himself an extensive show of some kind. And I expect it to be disgusting.

Red, you have some good points, but I think the difference is between arresting local LGBT activists vs. international athletes. One party Russia has authority over, the other could lead to more political and economic losses than Putin can risk.

I don’t think the United States will boycott, if only because there is still a great deal of dissent in this country when it comes to gay and lesbian rights (Ken Cuccinelli, for example). I’d rather see our athletes go to Sochi and win all the things, and wear some sort of patch or pin expressing their support for the GLBT community. Russia already has poor relations with the US due to their offer of asylum to Snowden, so I don’t think they would damage those relations more by threatening a US athlete who shows support or solidarity with gay and lesbian citizens.

“[…] and wear some sort of patch or pin expressing their support for the GLBT community […]”

Umm… they can get prosecuted for doing that…

Really, Obama, “nobody’s more offended”? I think of, I dunno, 10% of the population that might be a little bit more offended than a straight guy that only supports LGBT politics when it’s politically convenient.

THANK YOU.

or um like, the LGBT people who… live there…

right?

BAM.

Also, for real. Obama’s really good at lip service and empty promises. Ok he’s offended but still going to send athletes and not do anything about it. Just like when he goes on The Tonight Show to espouse transparency in his surveillance policies and then meets secretly and off-the-record with tech companies about the same issue.

I’m not watching. Simple as that.

Okay, I freaking LOVE LOVE LOVE the Olympics, especially the winter Games, and I’ve been looking forward to Sochi since the Vancouver Games ended.

That being said, I absolutely recognize the problematic nature of the Olympics – millions spent, homeless ejected from the city, whitewashing problems of colonialism and racism, capitalism, etc. etc. etc.

HOWEVER. I completely agree with Anita Sarkeesian. She was referring to video games, but you replace one word, and it can be applied to almost anything:

“It is both possible and even necessary to simultaneously enjoy [the Olympics] while also being critical of its more problematic or pernicious aspects.”

I don’t support a boycott. Partly because I feel for the athletes, because I love the Olympics wholeheartedly, and because LGBT activists in Russia have expressed the wish that countries NOT boycott or move the Games, to allow them to protest. I will also be watching the Games from home, thus the only people making money from me will be the media outlets in Canada and Canadian advertisers, not Russia. What I DO support is the decision not to attend the Games in person, therefor robbing Russia of a great deal of revenue. Moreover, I think the best thing that can be done is to have media all over the world bring attention to Russia’s hateful laws. While reporters on the ground in Russia could face arrest under these laws for talking about LGBT rights, reporters not physically in Russia cannot be subject to these laws, and it is here that the world media MUST bring its considerable voice to protest these laws.

I really hope the IOC steps up its game sometime in the next 6 months. I really hope they loosen the ban on political speech by athletes. But if they don’t, and athletes fear taking a stand at the Games because they might loose their medals, or sponsors, or because they fear Russia’s laws, it will fall to the media to make the world pay attention. I hope they are up for the task.

I love the olympics. It think it’s awesome to see so many countries come together and participate in the games with each other. I find the solidarity touching and inspiring.

After reading this story and I wish I could do something about this. There are SO many people involved in an event like this and the whole world is watching.

I hope a clear, peaceful message is given about this rubbish in Russia, for the whole world to see.

An alternative Olympics… What if another location was chosen as an alternative and nations could boycott Sochi but still participate in the other location? (As was mentioned in the case of the 1936 Berlin Olympics.) I’m not sure of the logistics of all of it, but it would be interesting…

I feel like if things go on as planned, there will probably be at least ONE athlete to defy their laws and make a stand. As much as I’d love to see it, I refuse to actually watch them. I wish we had a better solution.

Sadly this is just the start of major sporting event’s that will be taking place in Russia, although it should be noted that the World Athletics Championship’s are currently taking place in Russia, although it’s some time away, in 2018 Russia will be hosting the FIFA World Cup, and event of huge proportions.

Next year Bernie Ecclestone is taking Formula 1 to Moscow (although I’m convinced he would take F1 to countries like Uganda if he could).

I’m all for mass protest or show of support from visiting countries and athletes, (as PaperOFlowers say’s;call their bluff).

It goes without saying that big sporting event’s are supposed to inclusive. I’m torn on organisations like the IOC and FIFA threatening to take these major events away as it masks the problems and leaves the LGBT community in Russia in limbo somewhat, removing a voice potential mass voice of protest, but they absolutely should be putting pressure on the Russian government to make changes.

It’s scary to think the problem could get worse over the next few years. Especially as said, the Winter Olympics are only the beginning.

How about advocating for change in the way western government handle LGBT asylum seekers applications so that Russians whose safety is seriously threatened can leave the country? It’s incredibly hard to gain asylum as an LGBT person even if you’re coming from a country with worse legislation and more homophobic violence than Russia. You’d think it’s easy getting asylum if you’re coming from notoriously homophobic countries like Uganda or Iran, but it’s not. Immigration officers routinely refuse to believe applicants are actually not straight / not cis or decide that applicants “over-estimate” the danger they face and send people back and advise them to “live discretely” i.e. just stay closeted forever.

Also am I the only person who finds the constant references to the 1936 Olympics really offensive ? to pretty much everyone ?

it’s like

several US states still have anti-sodomy laws on the books – hell, homosexuality was only decriminalized in the US 10 years ago – yet although anti-sodomy laws are a much more severe form of the criminalization of homosexuality, I don’t see you talking about how ‘muricans are about to gather up all the gays and send them to death camps. We just have different expectations for western and non-western homophobes, you know? we expect non-western people to be nazis, we expect them to be genocidal, destructive and thoughtlessly violent – we say, look at their barbaric culture and their backward religions etc to confirm this (Stephen Fry has done this very explicitly). On the other hand, we expect western homophobes to be cruel but we don’t expect their cruelty to be an inherent of their / our culture. They are cruel individuals, but we believe our culture is inherently kind / tolerant / good – we believe change will because it must come and we tell these people to “get on with the times”. We expect things to keep getting better here in the West because we have a lot of trust in western culture’s inherent compatibility with “human rights” – we expect things to get progressively worse in Russia because we don’t see Russian culture as compatible with “human rights” in the same way, we see it as inherently unstable, violent, cruel etc and ominously declare “this is just the start, they’ll start sending people to camps etc”.

Great points on our assumptions! Russia has had a love/hate, envy/fear relationship with W Eur for centuries. Russia IS European, but then not quite. I am also tired of the countless Nazi analogies (lazy thinking) — let’ s look directly at the situation in front of us. At the same time, Russia’s rounding up people and sending them to camps (or killing them directly on the ground) is real and recent.

Get your facts right Andreea, there are, in fact, zero states which have anti-sodomy laws in the US. But I get your point, yes, there are places which are still quite inhospitable to LGBTQ people (as there are in EVERY country).

But let’s not equate that to what’s going on in Russia right now… speaking of making false analogies. As a Jewish woman who has tangible Russian family connections and is a trans person, I’m completely comfortable making analogies between 1936 and what’s going on in Russia in 2013. No, Russia doesn’t currently have death camps (although their 230+ year old genocidal policies in the Caucasus are very much equivalent to what the US and Spain did to indigenous peoples in the Americas) but then, neither did Germany in 1936 (although Stalin had already created the Ukrainian famine in the early 30s murdering millions). There are LOTS of countries with shameful pasts. Portugal, Japan and Belgium had some of the worst and most brutal colonial records of any nations. The question is, what’s going on now in the host country. The fact that the Russian government frequently allows skinheads, Orthodox zealots, self-described ‘slavic nationalists’ and street thugs to attack LGBTQ people (and non-slavic people) on the street with few consequences is very analogous to what brownshirts were allowed to do to Jews, socialist and gay men in the late 30s.

I do agree agree with you that immigration policies need to be greatly eased on people who are experiencing anti gay/queer/trans violence in their own countries and that this should be a logical response to Russia homo/transphobia (The US government was were all too ready to accept fundamentalist Russian Baptists into this country… there are a ton of them where I live). Unfortunately, in the US there are lots of people who would love to do this yet we’re tied up in partisan politics and right wingers exploit immigration in much the same way it’s done in the UK.

Thank you.

13 states still have anti-sodomy laws on the books, they can’t be enacted because of Lawrence v. Texas but they haven’t been repealed and if Lawrence v. Texas gets struck down, they’ll be enacted again – in some of these states kids are taught that homosexuality is illegal in sex ed – http://www.salon.com/2013/03/21/alabama_sex_education_law_requires_teachers_to_say_that_being_gay_is_illegal/

plus the Virginia’s attorney general recently expressed his desire to make sodomy illegal – http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/jurisprudence/2013/08/ken_cuccinelli_s_sodomy_obsession_the_frightening_legal_implications_of.html

it’s clear that a considerable number of Americans still support these laws

why did I think it would make a difference if I tried to explain this politely? I am sorry that I and other eastern european queers have been trying to rob you, Our Great American Masters, of your god given right to insult and denigrate all non-western cultures ? I guess if you have ~*~tangible family connections~*~ you must know more about eastern europe than I do – you must be more eastern european than I am – I can’t begin to describe how condescending it is for you to start giving me a history lesson – “let me explain to you what your experiences are” – “you are clearly not qualified to speak about them because, you see, they might be your lived experience but I have TANGIBLE family connections with Russia, thus I know SO much more about this than you’ll ever know”

do you know how condescending it is for you to use the fact that queer people are attacked on the streets as an argument – do you think I don’t know this ? do you think I don’t live with the fear of that happening to me ?

just because I know that violence against us is condoned doesn’t mean I must think my people are nazis, doesn’t mean I must approve of foreigners denigrating us – doesn’t mean I must believe we are inherently backward and uncivilized, inherently violent, inherently lesser than you – it’s not like violence against queer people isn’t condoned in the US as well? – didn’t a disabled gay kid die because bullies set him on fire in England a few months ago? I’ve never heard of anything like that happening anywhere in Eastern Europe – but imagine if it had, imagine the news coverage in western countries, imagine you all super concerned about it

but it’s okay, please, go on, I guess you, and all other Americans with ~*~tangible family connections~*~ are entitled to speaking over us and cutting our voices out of this conversation as much as possible

this conversation was never about Russian or Eastern European LGBTs, let’s be real – it was always about Americans – what are you gonna do – you’re not gonna do anything – you don’t want to do anything for LGBTs in other countries, hence the disinterest in advocating for better conditions for asylum seekers and eliminating institutional homophobia in asylum seeking processes – which are much more realistic, achievable short term goals than trying to change legislation in a different country (especially given the relative success of DREAMers which has proven that immigration reform is not impossible to achieve – but I forget that mainstream queer movements ignore that since it’s not about white people)

what you’re gonna do is brag about how, again, the Great and Glorious American Empire has attempted to civilize the barbarians but unfortunately failed because it’s very hard to reform backward cultures and peoples – then the Olympics will be over and you’ll move on and forget all about it

@Andreea THANK YOU!

as a jamaican-american queer who has to suffer through similar patronizing rhetoric from white americans, i hear& appreciate your anger.

Andreea,

Speaking of talking over, what’s your direct connection to the analogy made about the 1936 Olympics? Are you Jewish or Romany or a gay man? Did you have family whose lives were impacted by the German racial policies? You seem to now be representing all Eastern Europeans (are you from the Russian Federation?). I didn’t know everyone from Eastern Europe gets an automatic ticket to speak for one another? Are you an LGBTQ person living in Russia, or do your people come from the lands brutally stolen by Russians who are holding the games in the very same area where thousands of people were murdered for those lands in 1861? Andreea, I never explained YOUR EXPERIENCES to you, unless you want to claim all queer/trans/gay people’s experiences in Eastern Europe as your own. Is that what you’re doing?

I wasn’t even vaguely contradicting what you said about the US dealing with its own evils (and I was completely against the Salt Lake City Olympics for many of the same reasons I’m against the Sochi games) but just like you get pissed about someone explaining history to you, nor do I need someone from another country to condescendingly explain the US’s own bs to us. Since you feel we’re all waiting with baited breath for you to illuminate our legal system to us, trying to use the analogy of what happened in a place like Baton Rouge (where 2 gay men were arrested for sodomy last year) is because of the actions of a local homophobe sheriff, not because of a law… because Louisiana’s sodomy law is no longer a law (being ‘on the books means nothing’). Just as many states still tried to enforce slavery era laws long after the 13th Amendment was ratified. They weren’t laws just because they were ‘on the books.’ I have zero doubt you loathe this explanation being made to you, but it was you who made the incorrect analogy between the US’s former anti-sodomy laws and Russia’s very current legal situation. You’re completely welcome to whatever opinions you have about the US, US/Russian relations or the hypocrisy of the US government speaking out about oppression within Russia but if you’re going to lecture us, then don’t expect your lecture to go unchallenged when it’s off.

@Andreea – you probably already know this, but seeing how it appears that you are addressing all Americans and the “Great and Glorious American Empire” in your previous post, I have to ask: I hope you do not believe that there aren’t any Americans that are supportive of LGBT’s in other countries?

I have one voice and I am not a member of congress. I have very little impact on the immigration policy because all I can do is write my congresswoman with my concerns. I only count as one vote on what few policies I am allowed to cast a vote on.

I am not an entitled white woman nor do I have any family in Russia that I am aware of (tangilbe or otherwise). I do not like our immigration policy but if you want me to “get real here,” that’s just one of hundreds of things that I do NOT like about the USA. I didn’t move to America because I thought it was a wonderful place to live and I didn’t choose the society I live in. It wasn’t my fault I was born here and surrounded by ‘Americans.’

I’ve often thought about moving to another country in recent years, but I seem to be at a loss in finding a country that embraces and supports its LGBT citizens (me), has decent health care that I would qualify for, isn’t fighting wars in other countries let alone their own, and/or isn’t hated all over the world over.

Like many human beings who aren’t born into money or wealth, my only reasonable option is to remain where I am at and make the best of it — educate myself, vote, find causes to support and donate to, and obey city, state and federal laws so I can keep the illusion that I have ‘freedom’ and choice. Oh, and hope that some lunatic(s) doesn’t ruin it for the rest of us – I might live with some crazy people, but that doesn’t mean I support them or agree with them. If I could vote them off the island I would!

My point is, I am LGBT and I have LGBT friends in 11 countries that I talk to on a daily basis. I DO care about their safety and well-being. I understand a LOT of the animosity toward the USA, as a country they have spent a couple centuries earning it but that doesn’t mean ‘every’ individual citizen has earned it or wants any part of it, and I realize that could be said by a citizen of any other country… well, unless it’s illegal to say that or know someone who says that.

Looking back at the title of the original post/article, this is about LGBTs, the Sochi Olympics and the laws and rules which effecting everyone involved – it’s a worldwide thing. Maybe we can work together on this? Everyone? :)

@Veronica K M

*psst* If you’re looking for a new country, why not move to New Zealand… we have gay marriage and cheap healthcare and a pretty easy immigration process for Americans… peace out.

You think “it is illegal to get caught having gay sex but also illegal to arrest anyone for it” is more severe than “it is illegal to get caught saying gay people exist, so go ahead and do whatever you want to these nonpersons”?

Some athletes are already calling their bluff, at the World Track & Field Championships, Nick Symmonds openly dedicated his silver medal in the 800m to his gay and lesbian friends and said he disagreed with the law.