I didn’t know Martin Luther King was human until I was already well out of high school.

That sounds awful, and would embarrass the people who raised me, let me try again:

I grew up as a “well behaved” Black girl in metro Detroit, which means that I firmly grew up within the shadow of Martin Luther King’s myth. If you’re Black, and especially if you’re Black and grew up in a major Black city any time in the last half century, you know the drill. You know the speeches, and the church breakfasts, the symbolic marches, and the documentaries. You know the service projects. You learn “I Have a Dream” well before most of your white peers, and by the time they’re finally covering the scrapped together basics of the civil rights movement, your parents have already so deeply instilled in you that you have to be twice as good to get half as much that Dr. King’s dream might as well just stay that — a dream. The King I knew was an icon. A martyr. Depending on whom you ask, a savior. But he was never a human being.

Usually when people talk of Dr. King’s humanity, they zero in on the ways he was fallible. They speak of his numerous affairs behind his wife’s back; they note that he didn’t do enough to stand up for one of his lead organizers, Bayard Rustin, when he faced rampant homophobia; sometimes they even mention that Dr. King enjoyed a bit of gambling on the side. What you hear less often is that he was only 26 years old when he led the Montgomery Bus Boycott. He was 34 at the March on Washington. He hadn’t even reached 40 when he was assassinated. Martin Luther King was a young man.

The first time this really occurred to me, it was because of a photo of Dr. King flirting with his wife, Coretta. It looks like it’s cold outside and she’s kissing him on his cheek, her gloved hand rested on his shoulder. His eyes are larger than usual, turned to the upper corner as if to put on a performative “aw shucks.” It’s silly and playful. I’ve seen hundreds photos just like it from couples on Instagram.

The next time I thought about how young Martin Luther King really was, it was when I saw him in a corner pressed against the performer Sammy Davis Jr. Sammy’s mouth is open so big with laughter, it’s almost doubled. King’s shoulders have hunched up so far, they’re at his ears. They’re definitely spilling some kinda tea, and it is HOT. There’s so much joy there, but looking at the picture makes me almost sad. Why was I an adult before someone bothered to tell me that Martin Luther King ever laughed?

Y’all I am tired.

There’s an expectation — on days like Martin Luther King Day or Black History Month, specifically — that Black folks — especially the Black folks who occupy liberal “woke” circles, like the kind often occupied in queer communities — will spend the day teaching. And to be fair, I’ve made my career teaching Black history. I joke that “Martin Luther King Day through February 28th is when I make most of my coin all year.” So, I definitely signed up for this and I knew what the deal was when I penned my signature. But, more than anything, this year, I want to wish Black queer and trans people joy. Martin Luther King didn’t fight that damn hard for us not to have a quality of life that comes with celebrating our joy and humanity first.

The desire to find footprints of something gay and happy and Black to write about led me back to Lorraine Hansberry and James Baldwin. Two Black queer writers whose friendship and intellectual partnership have become a myth of its own right. A Black gay man that for many QTPOC, “venerable” would only be the beginning — an understatement of what he’s meant to us when words stop having meaning. To Lorraine, he was Jimmy. She was closeted lesbian playwright and essayist whose most famous work, A Raisin in the Sun, is still performed by high schools in every city nationwide, so much so that it borders on cliché. He simply called her “Sweet Lorraine.”

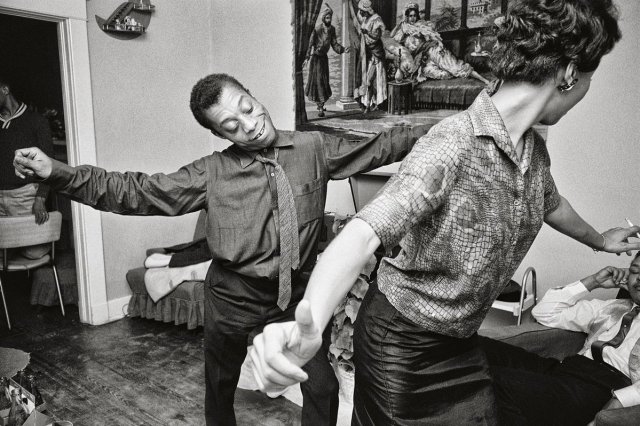

If you’re a Black queer nerd (or perhaps even if you’re not) there’s a photo that’s probably being conjured in your mind right now. In it, James Baldwin’s smile takes up half his face. His arms are wide. His tie’s askew. His hips are rocking to beat that, even in a still image, you can somehow hear. Lorraine is facing away from the camera, snapping her fingers to the same tune. She doesn’t let go of her famous cigarette. It’s the kind of photo that gets shared every year on his birthday, on her birthday, whenever someone wants to spark a little fun on social media timelines.

Here’s something most people won’t tell you: That’s not Lorraine in the picture. It’s an unnamed CORE worker in New Orleans. The reason the photo is shared prolifically and is so closely associated to Hansberry and Baldwin, however, is because it perfectly encapsulates their friendship. Here they are, as described in Baldwin’s own words in the essay he named after her nickname, “Sweet Lorraine:”

We walked and talked and laughed and drank together, sometimes in the streets and bars and restaurants of the Village, sometimes at her house, gracelessly fleeing the houses of others; and sometimes seeming, for anyone who didn’t know us, to be having a knock-down-drag-out battle. We spent a lot of time arguing about history and tremendously related subjects in her Bleecker Street, and later Waverly Place, flats. And often, just when I was certain that she was about to throw me out as being altogether too rowdy a type, she would stand up, her hands on her hips (for these down-home sessions she always wore slacks), and pick up my empty glass as though she intended to throw it at me. Then she would walk into the kitchen, saying, with a haughty toss of her head, “Really, Jimmy. You ain’t right, child!” With which stern put-down she would hand me another drink and launch into a brilliant analysis of just why I wasn’t “right.” I would often stagger down her stairs as the sun came up, usually in the middle of a paragraph and always in the middle of a laugh. That marvelous laugh. That marvelous face. I loved her, she was my sister.

That marvelous laugh. That marvelous face. I loved her, she was my sister.

You know the phrase a picture is worth a thousand words? Well this might be one of those few times when the words do it better.

It’s the rowdiness. The unbridled laughter, so loud that others would mistake it for a fight. The hands on the hips and name calling. The stumbling home at dawn that still doesn’t feel like an ending, only an ellipsis of what’s next to come. That’s the story I want to talk about today.

James Baldwin was at the March on Washington, of course — as was almost every other Black person with even a modicum of intellectual or political celebrity (ironically, Lorraine Hansberry was not; she was at home recovering from surgery). Those famously drawn moments, with their stoic black and white photographs and stern promises of a better tomorrow, are important. Their performance of “respectability politics” that asked Black activists to wear their supposed Sunday best for long walks in blazing sun as a proof of their humanity for white people who never gave them a second thought in the first place — that’s important. Those are stories of heroes that I learned as a child, and I don’t take them for granted. Not for a second. And most certainly, not on this day.

But this? This after-hours queer mess, full of sweat and entangled limbs and exuberant slurred words? These stories of bossy femmes in slacks who made a home out of their kitchen for their smartass friends to bang tables and talk loud? Of Black queer folk who loved on themselves in the middle of the night, and together built a family of children that, nearly 60 years later, they’d never get to meet? That’s what I find myself most clamoring to remember.

It’s not about who we are when the cameras are turned on, but the ways we care for each other when no one is looking but us. When we’re exhausted from this fight. When we have to promise ourselves that we’re worth it right now. When kisses and laughter are our ports in the storm.