I will not hesitate to say that I won the parent lottery. My mom and dad have been almost uncomfortably supportive (The L Word became family hour for a few years, no joke) at every big moment, from basketball games to choir concerts to coming out to surgeries to graduations to writing for Autostraddle. And as far as my disability goes, I honestly don’t know how they could have negotiated it better.

As a kid, my mom pulled me out of activities if she felt I was being patronized or talked down to. She gave me her copy of No Pity: People with Disabilities Forging a New Civil Rights Movement a couple years ago, and I discovered it was lined with her handwritten notes. My dad held down the fort whenever a big operation kept me in bed for months, watching TV with me at 1 AM and making sure I got out of the house. They fought for me at school, equipped me with the right language for difficult conversations, and treated my sister and me like full people with valuable opinions from our first conversations around the dinner table. I never once felt unsafe in their care — which shouldn’t be unusual in the slightest. But for far too many disabled folks, the opposite is the case.

Last Wednesday marked the annual Disability Day of Mourning, honoring disabled people who’ve been murdered by their caregivers or relatives. Before you question whether that really happens, think about how often you’ve heard, explicitly or otherwise, that disabled kids “must be so hard on a family.” Remember that in July of last year, the man who killed 19 people at the Tsukui Yamayuri-en residential care center in Sagamihara, Japan was a former employee there. Consider that, according to the Autistic Self Advocacy Network (ASAN), over 400 disabled people have been murdered by their parents in the past five years.

Yes, disability is a family issue. Yes, it’s exhausting and taxing and bewildering for all parties at one point or another. But that’s absolutely no excuse for an all-too-common crime that often gets written off as understandable — or even merciful.

No one wants to believe that these realities are part of the disabled experience. But the longer we remain silent and ignorant of them, the longer they’ll be allowed to persist. So in that spirit, here are eight queer disabled folks — including a few familiar faces to Autostraddle readers and some heavy hitters in the disability rights movement — discussing how they marked this year’s DDOM and what it means to them.

Victoria / 28 / Washington, D.C.

A few weeks before DDOM, Zoe Gross of the Autistic Self Advocacy Network asked me if I’d be willing to, once again, speak at the Day of Mourning event. Because it was a rainy day in Washington, the event took place indoors at the National Youth Transitions Center building in the Foggy Bottom area.

My remarks centered around the fact that our advocacy at this time often feels like a Sisyphean task — you push the boulder only for it to slip and suddenly roll back down. What I wanted to remind everyone there that night was that, to paraphrase José Martí, even when there are many honorless people, there are always a few with the honor of many. Personally — and I am not a hundred percent sure I should admit this — but I kept my remarks short in order to keep myself from crying mid-speech. There were four panels full to the brim of names, and far too often they are reminiscent of the limitations of our advocacy and the extent to which we work so hard to try to make sure that no one else has to die.

“Our advocacy at this time often feels like a Sisyphean task — you push the boulder only for it to slip and suddenly roll back down. What I wanted to remind everyone was that, to paraphrase José Martí, even when there are many honorless people, there are always a few with the honor of many.”

After that, Zoe and Julia Bascom led the process with various attendants reading aloud the names. This year it was around 750 names. All of them are read, even the ones of prior years, because far too often, that moment is the only time that many of them ever receive any remembrance. However, as Zoe remarked, the list is growing so much that this may well be the last year we can read them all.

I generally have scented candles at my house. Once I made it home later that evening, I made sure to light at least one of the candles. I do this on Trans Day of Remembrance, too.

Sara / 27 / Washington, D.C.

I attended a vigil organized by ASAN in Washington, D.C. I am autistic; I had a lot of problem behaviors as a kid. I know my parents didn’t have an easy time of it, and I don’t think it should be a death sentence for anybody.

Alaina / 24 / Boston, MA

I spent as much time as I could that day focused on disability rights. For me, that meant working on pieces I’d pitched that were disability-focused and sensitivity reading a middle grade/young adult manuscript with a disabled character. I also took the day to read work by other disabled folks and to boost the work others are doing on social media.

I was able to spend some time working on a piece I’ve got in the pipeline about being empathetic and autistic, and another piece I’m writing about life at the intersections of queerness and disability. Both pieces feature other disabled voices, too, which gives me a chance to boost the work of activists and writers who have had a positive impact on me. I also donated to a couple of folks’ #DisabilityCrowdfund campaigns, which is something I’m not always able to do because of finances, but I always encourage those with the means to help out.

“I want to celebrate and enhance the lives of disabled folks, and show that we all have value and deserve to live happy, full lives.”

There’s this myth that disabled folks can easily get access to the medical care, mobility aids, and other medical necessities we may need, and it’s just not true — so if I can give $10 to help someone buy a new wheelchair, or pay for their trip to the hospital, I’m happy to. I don’t want to add any more names to the Disability Day of Mourning. I want to celebrate and enhance the lives of disabled folks, and show that we all have value and deserve to live happy, full lives.

I’m physically and learning disabled, and I’m well aware of the ways that ableism allows people to become victims to systemic violence. I’m very fortunate that I was raised by two loving, also disabled parents, but not everyone is that lucky. Many people are at risk for institutional abuse by educators, medical professionals, disability housing staff, personal care assistants or caregivers, law enforcement (especially for trans disabled folks or disabled people of color), or anyone else that’s supposed to protect and support us. I want to do everything I can do to be a part of the disability rights movement in a way that’s dismantling systemic oppression, uplifting the disability community, and supporting intersectionality.

“There’s this myth that disabled folks can easily get access to the medical care, mobility aids, and other medical necessities we may need, and it’s just not true.”

As a writer and editor, it’s a focus of my career to make sure that disabled folks are spoken about and treated with respect in the media. That includes showcasing difficult truths sometimes, like the fact that disabled folks are more likely to be victims to violence, murder, and sexual violence, because educating people about these issues is a step toward making meaningful change.

Eleanor / 16 / Orange County, CA

I posted about the Disability Day of Mourning on social media with info on why it is important. I wanted to bring awareness to the fact that disabled people are murdered for simply being disabled.

I am a disabled teen and many of my friends are as well. We are not burdens and we don’t deserve to die because we are disabled. Neither does anyone else. It is important to recognize and bring light to this issue that often goes unseen and honor or and remember those who have been murdered for being disabled.

“We are not burdens and we don’t deserve to die because we are disabled. We must always protect disabled people.”

I’d like to reach out to other disabled people (especially kids and teens) who are in an unsafe environment to be disabled and offer support. I’d like to bring this day and this issue to light not only in the disabled community but beyond — because we often don’t hear about it. This fight is daily and doesn’t end when this day ends. We must always protect disabled people.

Mia / 36 / Oakland, CA

I lit a candle and took some time in silence. The DDOM means so much to me because ultimately my work to respond to and end child sexual abuse is about how we can build a world to keep children — all children — safe, especially in our families and communities. Every day I work to respond to and end intimate and sexual violence, always knowing that when it comes to disabled communities, the statistics around these double, triple, and in some studies quadruple. It is one thing to fight against state violence and the violence of strangers, but it is another to fight the violence from our kin, families, communities, and people who reflect us. I think DDOM shines an important light on the kinds of dangers that disabled children and adults face every day. For example, it is not enough for us to work to get disabled people out of abusive group homes, institutions or prisons, especially when we cannot guarantee them anything safer in our “communities” or homes; we must also work to change our families, intimate networks and communities.

“It is one thing to fight against state violence and the violence of strangers, but it is another to fight the violence from our kin, families, communities and people who reflect us.”

DDOM emphasizes the thick stigma that still surrounds our communities and the ways that ableism, a culture of victim blaming, the myth of independence, capitalism, romanticized ideas of parenting and a society invested in the ownership of children and land collide, putting disabled people at the mercy of our caretakers, who are often our family members.

I used to have a Google alert for stories about disabled children and violence, but I eventually had to delete it because every day I would get so many notifications that it was overwhelming. And all of the stories followed such similar patterns: abuse, torture, neglect, and many times murder that were all justified and went unaccountable. Even when there were multiple murderers, even when the disabled children were adults.

“I want to live in a world where disabled lives are valued and where disabled people get to be understood as human, and not merely as burdens or tragedies or reminders of ‘how bad your life could be.’”

I want to live in a world where disabled lives are valued and where disabled people get to be understood as human, and not merely as burdens or tragedies or reminders of “how bad your life could be.” I want us to get to be free and not projects for our parents or doctors to save or experiment on. I want people to care about the hundreds and hundreds of disabled people who are murdered by their parents and caretakers and stop pretending that caretakers, parents, and family members of disabled people can’t be ableist — because they can often be some of the most ableist people.

I also want to hold space for the millions of disabled children, youth, and people who are surviving daily abuse and torture at the hands of their caretakers, doctors and medical providers, facility staff, teachers, religious leaders, family and communities, that hasn’t ended in death. Yet.

Angel / 24 / Buffalo, NY

I wasn’t aware DDOM was a thing, actually, until this year — but it doesn’t surprise me. I think it’s super necessary; I’d always known that people had abused or harmed disabled people they were charged with caring for. Sometimes they don’t face any consequences, due to this idea that they’re just so overwhelmed by the amount of care required. Being overwhelmed is completely valid — but I call BS on using that as an excuse. There’s no excuse for killing your six-year-old child or an adult either. They didn’t ask to be disabled and require that care. It especially makes me upset with people who know they have resources! People without as many or any of those don’t get a pass from me either, though.

“Sometimes they don’t face any consequences, due to this idea that they’re just so overwhelmed by the amount of care required. Being overwhelmed is completely valid — but I call BS on using that as an excuse.”

Then there’s a matter of genuine abuse of disabled people, be that physical, sexual, mental, and/or emotional. I don’t think we focus on those last two enough. Being raised by able people as a disabled person can be hellish, mostly because they feel they know what’s best, when sometimes they just don’t — and they don’t realize they’re ableist, and teaching what will end up becoming internalized ableism. Additionally, I remember growing up and being afraid to go to camp or have an in-home aide as a kid, because I was so scared that someone would harm me. I think that’s a defense you’ll always have as a disabled person, especially when you look at stats for disabled people who are sexually assaulted or physically abused by able partners. In a way, you always have some kind of wall up. it’s just always there.

“Being raised by able people as a disabled person can be hellish, mostly because they feel they know what’s best, when sometimes they just don’t — and they don’t realize they’re ableist, and teaching what will end up becoming internalized ableism.”

Many people don’t see ableism as a form of bigotry and that drives me crazy. So many people have this view that having a disability is such a horrid thing, but they don’t see themselves as being ableist. Don’t get me wrong: being disabled is not easy for everyone to accept — for me, it’ll be a lifetime acceptance thing — but some of us don’t even think about what life would be like as an able person. It is considered hateful to kill someone because of their race, gender, sexuality, and religion, but we don’t as often hear “Well, they were just so overwhelmed by seeing a person of color,” or “They were just so overwhelmed by meeting an atheist.” It does come up in the current political climate more and more, but it’s still much less common than with disability.

Fuck that, all of it. If you kill someone because of their disability, you are just as bad as the aforementioned.

Sandy / 29 / Boston, MA

This year I observed DDOM through education and reflection. I have the opportunity to co-teach an undergraduate class on disability studies this semester, and it’s balanced between disabled and nondisabled students. Not many of the students had heard of the Disability Day of Mourning before, and another student mentioned that she would be attending the vigil that was happening in Harvard Square organized by ASAN Boston. That class, we had spoken about the various models of disability (medical/social/charity/economic), and how the deeply stigmatized, cure-centric ways in which disability is positioned have directly led to the need for a Disability Day of Mourning.

So often in the media we only hear about the caregiver’s perspective on the death of a disabled person, and in this way, the death is unjustly positioned as a tragedy when in fact it is outright murder. I think that encouraging students in our class to look critically at events, news articles, and other media with a more analytical eye was a new way for me to observe DDOM than I had in the past. It pushed me to center this day as an unavoidable part of disability culture and lived experience.

“The deeply stigmatized, cure-centric ways in which disability is positioned have directly led to the need for a Disability Day of Mourning.”

This day is important to me because as a child of Asian parents I know that in Asian culture, disability is openly seen as something that is a burden for caregivers. You can see that in the media coverage of Sagamihara. I grew up being told “You should be grateful you were born in the U.S.” because of the advances in medical care I received, but also because disabled people in America are able to exist in spaces (school, work, home, community) that are not accessible to disabled people in many Asian countries. Not only are the spaces inaccessible, but living a disabled life is not even an option — and this for me, is what gets to the essence of DDOM.

The day is meaningful to me because this is an area I’m still working on gathering the language to talk about with my own family, and it’s important to me that as a disability community, we honor the lives that go unreported. I don’t just mourn and reflect on the deaths by caregivers; it is also important to me that we remember the lives that are stolen from disabled people by their families.

“The day is meaningful to me because this is an area I’m still working on gathering the language to talk about with my own family, and it’s important to me that as a disability community, we honor the lives that go unreported.”

To those observing I would say: please remember that grief comes in different forms, and is managed by individuals in widely varying ways. To that end, I realize that DDOM is intended to remember the people with disabilities who were killed at the hands of caregivers or family members — but I don’t think it serves anyone if we exclude the disabled lives who were killed at the hands of medical professionals, police officers, or institutionalized settings.

The reality is that I doubt Disability Day of Mourning is going away, particularly with how violently politicized healthcare has become for its recipients. But I hope we can all progress from this day by remembering all of the lives lost fiercely.

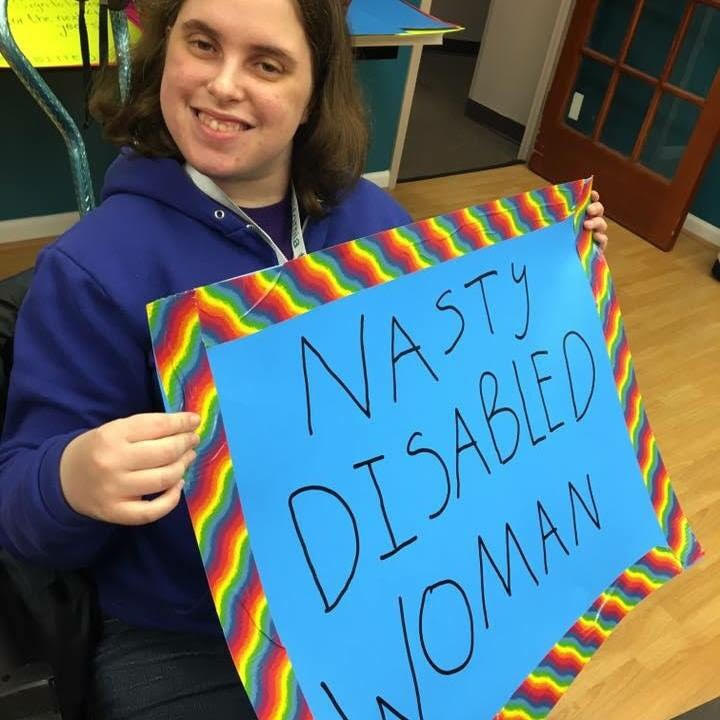

Cara / 24 / Washington, D.C.

I went to the national vigil in Washington, D.C. I volunteered to read some of the names and it was really emotional on a level I don’t think I can even describe. The names sort of blur together after a certain point, but you’re still very conscious that each one was a person, was a life worth living. I got up and made a speech, and that wasn’t something that I planned at all, but I was just so moved and I wanted to share my feelings on the murder of Julie Cirella a few years ago — she lived near me and I knew people who knew her. Julia Bascom from ASAN read Laura Hershey’s poem “You Get Proud by Practicing” at the end and it was the perfect reminder that in the midst of all this grief and uncertainty, that we must rise up and practice pride every day.

“In the midst of all this grief and uncertainty, we must rise up and practice pride every day.”

Simply put, these are my people. My people are being murdered. And it could be me next, or you, or any other disabled person. People always tell me “Oh, that won’t happen to you because you can walk, because you can talk, because you have a family that loves you, because, because, because…” but the thing is, I bet all those people whose names we read every Day of Mourning thought it wouldn’t happen to them either. All ages, all disabilities, there’s no pattern, except murder. So yes, it could happen to me, and that’s fucking scary as hell. The DDOM is important because these people need to be remembered, and we need to recognize that it hasn’t happened to the people reading the names in a room yet because we’re lucky. That’s it, that’s just it. It’s luck. Nothing more and nothing less.

“Simply put, these are my people. My people are being murdered… I don’t care if you’re big or small, if you do direct service or advocacy — this as an issue that affects us all.”

All disability organizations should be marking the DDOM. I don’t care if you’re big or small, if you do direct service or advocacy — this is an issue that affects us all. Our people are dying. I can think of at least two disability organizations right off the bat who didn’t acknowledge Day of Mourning on their social media at all, organizations that definitely should know better. For just one day, one day, we need to focus on the fact that people. Are. Dying. They’re being murdered, and there’s no outcry, very little media attention… the world needs to sit up and take notice.

For more on the Disability Day of Mourning visit disability-memorial.org and the #DDOM2017 and #DDOM17 hashtags on Twitter.