Once upon a time, Ruth Curry and I were teenagers with gassy stomachs from the cafeteria food at a liberal arts college in small town Minnesota. Both of us had different kinds of dye in our hair. We lived in a dormitory called Goodhue that was so far away from the rest of the dorms that we were forced to scream Sinead O’Connor lyrics deep into the night to entertain ourselves. We became English majors. She gave me a very brief lecture about some sex stuff in or around Waterloo Station when we were studying abroad in London. I realized that she was going to be a superstar when I heard her interviewed on a New York City radio show for which I had once been an intern delivering coffee to my literary crushes, Zadie Smith and Zadie Smith’s husband.

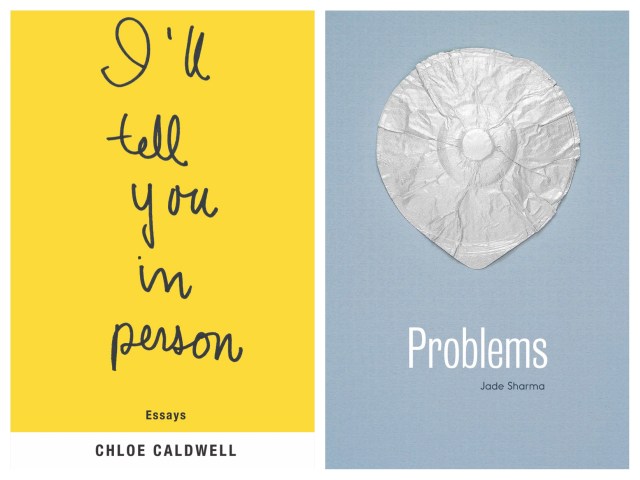

So I wasn’t surprised when she announced that she and her friend Emily Gould were going to partner with Coffee House Press to create an imprint called Emily Books, based on their e-bookstore of the same name. This July, they published the novel Problems by Jade Sharma, which was just nominated for a PEN Book Award. I’ll Tell You in Person, an essay collection by Chloe Caldwell (of Women fame) came out in October. The response to both books has been so positive that Ruth can barely believe it.

Recently, we sat down for a very sweaty Skype interview to discuss things like vodka’s effect on reading glasses, unlearning white heteronormative narratives, sex work, Chris Kraus, and Parker Posey. What follows is an edited version of that nigh-two-hour-long conversation.

Aisha: So, basically, you started a company with your best friend. Please tell our readers the story of how you and Emily [Gould] met.

Ruth: I interviewed for a job way back in 2005 that I really really wanted. I was one of the final two candidates but I didn’t get it, and I was devastated. They kept my resume on file, though, and a few months later I got a call about an opening for another position at the same place. So I got THAT job. But I was curious about the girl who got “my” job. And then I met her and it was Emily. I complimented something she had written (without knowing it was her who wrote it, it was anonymous)—which is a great way to win over a writer. Then I started going over to her house to watch America’s Next Top Model, because she was the only person I knew who had cable. We’ve been friends ever since.

How did your e-bookstore morph into an imprint at Coffee House Books?

I did an internship at Coffee House as an undergrad, and Glory Goes and Gets Some (A Coffee House Press book) was one of our first picks for the club. Chris Fischbach [the publisher of Coffee House] was in touch about something else and mentioned that he was looking for freelance acquisitions editors because they were trying to expand their list, and get more voices, more diversity, and he asked if I knew anyone.

At the same time Emily had been agitating us to move into print — which I was against, I thought, “Everything about print is too hard. We can’t do it. I don’t want to. Let’s stop talking about this.” But a part of me was listening. We had kind of reached this plateau where it was like, okay, we have this core group of people who will read e-books and like the books that we pick. We need to expand beyond that tiny intersection of the Venn diagram.” So I thought, well, what if someone else was willing to help with all the stuff we can’t do, like warehousing and distribution and print/paper/bind? And that was when Chris happened to write. So we started talking about a collaboration. That was in 2014, and now here we are!

When did you realize you were entrepreneurial goddesses?

I think when this review ran in the New York Times? Still waiting for that realization to hit our bank accounts though.

I know you wear glasses sometimes and I was wondering: what kinds of glasses do you wear when you talk to Chris Fischbach [Publisher at Coffee House]. And do you ever think about conversations with him when you’re purchasing glasses?

Let me just get my glasses, I have two pair. I recently purchased a new pair of glasses and then broke them a few weeks later—

Oh yeah. With the vodka.

But I do wear them sometimes because I can’t let them go and they’re so fucking cute. And once I was told that I looked like Tina Fey while I was wearing them. So here’s one. [Displays glasses]

OK. Excellent. I think I’ve seen you in those.

I have a memory of sitting on the kitchen counter in the apartment you had, the first apartment you had with N., feeling very much self aware of, I think I was visiting from Boston—

That sounds right.

And thinking: this is us in New York at this time in our lives.

Yeah that’s one thing about living in New York it’s really easy to start living the life of your movie New York.

That’s actually a question I was going to ask. Can you come up with a movie for when you first moved to New York versus now?

When I first moved here, that movie about just graduating from college, Kicking and Screaming. That would be my first year. It’s annoyingly white and rich white people’s problems, but it does get at this idea of unbridled chaos and confusion, and some of your friends have real jobs and some of them are sleeping all day and where do you fit in all this. And some of them are moving to Prague, should you move to Prague? Should you move back in with your parents? They all seem like very viable options.

The two ideas I had for the cinematic vixen that you are currently living is either Meryl Streep in The Devil Wears Prada or Glenn Close in 101 Dalmatians. The fierce aspects, not the evil part. The bad bitch.

That’s a great reminder because if anything my first year was like Anne Hathaway in The Devil Wears Prada.

AND NOW YOU’RE MERYL STREEP.

Well, I mean.

In my mind.

I feel it’s very important to stress how unsuccessful I am financially. I don’t have nice clothes or a nice house.

Or a coat made of Dalmatians.

I have never seen that movie but I don’t have a coat made of Dalmatians. So as far as contemporary, I feel kind of like, you know Party Girl?

Yeah.

Just in the sense that at the end she’s like, “Here I am, I’m a librarian,” and she’s always been meant to be a librarian and she’s so good at it. But there’s another that’s more bittersweet. A Nicole Holofcener movie. She made that movie with Julia Louis Dreyfus and James Gandolfini.

I loved that movie.

She did Friends with Money. Lovely and Amazing. The one I’m thinking of is the one with two close friends and one of them gets married. It’s amazing and it stands up really well even though a plot point hangs on an answering machine.

Anne Heche and—

Catherine Keener who is so amazing in everything. I think that one’s called Kicking and Screaming too—wouldn’t that be funny if both of my movies were called Kicking and Screaming? No wait, it’s called Walking and Talking.

Walking and Talking. Kicking and Screaming.

Or Noah Baumbach movies. Like While We’re Young, which I don’t feel applies to my life but just the way it: your choices have led you here and now there is now no backward motion. Only forward or staying in the same place.

Which is so funny because you probably represent to the publishing world more the millennial perspective.

Right. I feel like for publishing, anyone who is comfortable with email represents… I’m a technology savant by those terms.

Do you feel like a millennial?

I feel too slow to be a millennial.

Do you think of that as your readership at all? Are you curious about hitting them? Not hitting them. Reaching them? Speaking to them?

I think that millennials are in large part responsible for what social change we have seen in the last five or ten years and in that sense we are speaking the same language — I don’t want to say speaking the same language. But we have a lot more in common with them than we do with our big brothers and sisters and people in their early to mid forties.

I get what you’re saying. They’re demanding the kind of diversity and storytelling that you’ve been trying to offer.

Whenever we hire a new intern Emily comes back and reports to me, “the kids are alright.”

They really are. I agree. But whenever you pick up Time Magazine, “millennial” is a nasty term in the media.

It’s a pejorative. I think that’s why I find it so hard to identify with any part of it even though when they draw generational boundaries it’s usually 1980. So you and I are literally on the margin. But I think that is like a, almost by, not fitting into millennials or gen x has made people our age in an interesting position where we’re not being directly marketed to or targeted for anything. We don’t have enough money, we don’t have the numbers. But I feel like we’re in a place where we can observe and learn from both. And we have very limited cross-cultural references that we can use to identify one another. Like, “Were you interested in sex when you watched My So Called Life”?

That’s a fascinating concept, this weird generational responsibility to be intermediaries, anticipate the needs of the generations that preceded us and follow us—

I never thought of our project like this but Emily and I have the DIY aesthetic of Riot Grrrl of the early 90s, and later punk, so we have more of the scope and the scale of what a millennial might have. The way that this is always skewered in the media is that they’re attention hungry or they think they’re special. But there is this idea that we don’t want to be counter culture, we want to be the culture.

At least one interview talked about you all approaching the word feminism with a little bit of trepidation or care, carefulness, calling it the “f” word. Can you talk a little bit about the trajectory of your relationship to that word from, say, college to now? Or even childhood to now? How your relationship has blossomed?

As you know, I was raised in a very conservative Christian family, and my mom listened to Rush Limbaugh while she was home with us during the day doing house stuff. So my first encounter with the word feminist was probably feminazi.

The church I grew up in wasn’t particularly oppressive to women in the way that some of them can be, but it was definitely — there were no women ministers, I wasn’t familiar with a lot of feminist issues. I never felt limited because of my gender, my parents were very, “it’s fine you can do whatever you want as long as you don’t move five hundred miles away from home, marry a dude, make money and… you can do whatever you want within this very specific middle class heteronormative, white narrative.” And I think that my journey was, and part of this happened at college when I was for the first time in an environment that was more than 1,000 people, was realizing or learning that the middle class white heteronormative narrative is a narrative. It’s not reality, it’s not the way things are, it’s a construct. And for people who don’t fall into that narrative there’s a huge, there are huge structural differences and obstacles to what you can overcome and our society is structured this way on purpose. So that was a lot, you know, the liberal arts education. And you know, meeting people who aren’t like you.

Like all your great friends in Goodhue.

I don’t know how that happened that I ended up with a core group of people that were like, women and queer women of color. One of the advantages of my background is that I wasn’t exposed to a lot of overt racism. That’s honestly the silver lining of my tv-less culture-less childhood is that I wasn’t exposed to that garbage.

What are some of the specific literary interactions that you had over time that fed that awakening?

For me it wasn’t so much a literary journey so much as it was a personal one of becoming close to people whose experiences were different than mine. I will never forget, this was after college, but I will never forget this moment that L. and I were waiting for a train together in New York, on a platform. And some dude just started screaming racial slurs at her. And they weren’t even the right ones. So she wasn’t paying attention to it but I was just like, “Shut the fuck up, shut the fuck up, stop talking to her, shut the fuck up.” And everyone around me was “oh, you know, crazy people are going to be crazy.” And I remember asking you a lot of questions. Like, “Can I touch your hair?” for example. But as far as literary steps. I think that African American Autobiography class I took sophomore year—you were in that class.

With Kofi.

Yeah, with Kofi. Which was the first time I read a lot of literature by people of color. I’m trying to think what else I took. There was a story in American Lit that is not popular or widely anthologized, but it’s an Elizabeth Stoddard story about internal resistance. And it was a very understated depiction of oppression that kind of shows how all of the escape routes aren’t escape routes. She has to marry this guy no matter what. And I remember thinking of that in the context of like, that was one of the first times I was like, “this is an explicitly feminist work.” The literary devices are, even though it’s portrayed as a very privileged demographic, the way it maps out the social structures was very eye opening for me. And then I guess our theory seminar, remember?

Uh, yes.

Learning how many ways you could put something together and take it apart. And how that’s always informed by a political agenda or point of view or place of power or powerlessness that’s important to identify.

So many people’s first encounter with theory is such a downer. But they really lit us on fire.

Yeah, these thoughts affect our lives. This is how our society recognizes legitimacy. And being able to identify and deconstruct these narratives is an important tool as a political agent.

Do you remember what you wrote about in that class?

I wrote about Streetcar [Named Desire] and I also wrote about, shit. That poem. Parrot imitating spring.

I’m wondering what kinds of texts inform your stylistic preferences right now. That also dovetails with the question of the aesthetic you guys are looking at—you’ve described it as “weird.” But I’m wondering if you can speak to that question of subtlety more generally.

I love this question. The book we turn to and reference and keep in the forefront of our minds more than any other right now or for the last five to eight years is I Love Dick by Chris Kraus, I don’t know if you’ve read it.

I haven’t read that but I love Chris Kraus.

Oh, man. She’s amazing. The thing about I Love Dick that is so powerful is that it basically comes down to the fact that all heterosexual relationships, or being a women who loves a man is a form of complicity in the patriarchy. And one must, you don’t have to, but you have to kind of come to terms with your role in your own oppression. And why does it feel natural? It’s a very, I’m oversimplifying it, but it’s three hundred pages of letters about how the personal is political. The narrator’s history as a thwarted artist while her husband is a respected academic scholar, this respected intellectual who’s paid for his work. And she is someone who is constantly marginalized, who was never taken seriously, who is flipping rental properties in a dying blue-collar town not just to support herself but also him to some extent.

Of course.

And that she is like, this relationship and her relationship to the relationship, to get really meta, has trapped her her entire life. And there’s this great line in it where she’s at a party with her husband and all of his peers and all of their wives, girlfriends, partners who she thinks of as her peers, they’re having these intellectual conversations while the women are excluded. They’re having all these intellectual conversations to the songs that their partners danced to in titty bars ten years ago. All the guys are talking about art and politics and theory and all the women are having these conversations with each other to the soundtrack of their twenties which was spent basically doing sex work to survive.

Chris Kraus seems like such an amazing example of a certain kind of subtlety and I wonder if you could just keep going with that.

Well I think one of the things that I respond to, we respond to aesthetically about that book is that the narrator’s name is Chris, the husband’s name is Sylvère, they live wherever the fuck in California, their whole entire social circle, even Dick actually, are named by name. But it’s a novel. It’s obviously a novel. If you’re willing to take it on its own terms even for thirty seconds it’s obviously a novel. So the blurring of fiction and nonfiction and how important that is as a feminist enterprise because we’ve been told our whole lives that what happens to us doesn’t matter, it’s not art, our stories are boring, they’re not worthy, stories about relationships are not what the great American novel is about. So the slippage between fiction and nonfiction, it’s first person, a very close first person, it doesn’t shy away, it’s not going to pan away from a difficult moment, you know, the camera’s going to stay on a difficult moment until you’re like, “I wish this would go somewhere else.” I think it’s very funny. Reports vary.

That seems like a very vital piece in your aesthetic pie. Humor seems essential to you.

Yes. There was an interview with Jade [Sharma] where she, someone asked if she used humor as a coping mechanism. And I thought she had a really good answer to that. I’m going to look it up, sorry. So she says, “as far as balance, I don’t think of humor as a way for the medicine to go down. I feel humor is a coping mechanism and something in my arsenal. I want the reader to enjoy reading it.” I like the idea that it’s something in your arsenal.

It’s like, and maybe this is getting too thinky with it, but if you’re dealing with all this upsetting and charged material, content, whatever, humor, laughter is an involuntary response. It’s almost sexual? You can’t ever, you can’t control it, and you are, the person who is making you laugh has power over you in that moment. I just like how that plays out. A lot of the books that we champion are about really dark awful shit that most people would maybe want to ignore, skip over, skim through, or portray the protagonist as a victim or a crazy person. So these are voices that are discounted for whatever reason. But you can’t deny that someone has power over you when they’re making you laugh, or they’re claiming some control in the moment. It’s so awful for someone you hate to make you laugh.

I think it speaks to the power of her writing that you can feel so caught up in it without realizing that it’s influencing you. Because it’s so easy to identify with her that it’s almost dangerous. You’re like, am I doing these things? It’s real blurry.

I think one of her greatest talents as a writer is saying that life is kind of a meaningless joke in as many ways as possible. It’s hard not to internalize that as you’re reading it over and over and over and over.

Not too long after reading that book I saw an article about how many NYU students are involved in sex work in order to stay up on tuition. And I feel like there’s something about the fact that you are championing writers whose narratives are really uncomfortable but that actually represent huge swaths of the population.

The thing I feel about that book that hasn’t caught a lot of critics’ attention is how much of an economic analysis that it is, in a lot of ways. This is a woman who is very smart, very talented, has a good education, and yes, she has major personal flaws. But she’s also living in a world where she can’t get a fucking job. She interviews at American Apparel or Urban Outfitters. She had a job and she lost it and it was part of the trigger to the unraveling of her life. And the best option available to her is sex work. And that’s, let’s just sit with that. There doesn’t have to be any judgment one way or another. I am 100% supportive of women’s choices to earn money in a way that makes sense to them. But I think the way that her economic circumstances are of this particular moment is I think really interesting regardless of the heroin complication, which really just adds pressure to the financial situation if you think of it. But there’s this really great moment where she says “I’ve been sucking dick for awhile for money but I think I’d like to try something else.” But you can’t put that on your resume.

You saw this book in grad school, right? You’ve had a lot of time with it—

Five years, six years.

How has it grown? I was really impressed with the seamlessness of the narrative. It was beautifully constructed. The episodic narrative — it’s finely tuned. And I’m wondering if you could talk about the editorial process.

It’s such a personal book. It’s not an autobiography, clearly. But it’s clear that she loves her narrator, it’s someone she’s spent a lot of time with. As have I at this point. And I love her too. I think that — I’m glad that you picked up on the way that the episodic structure works, it’s a really important part of the book. Because one of my first instincts was to get my mind around the story was, “let’s get some chapters.” And she was like, “I don’t want chapters. I wrote this book as floating blocks, that’s what it’s always been, that’s what it is, do whatever else you want, but I do not want chapters.” And I was kind of like, “Ugh.” But she was absolutely right. As an editor and a writer those are very challenging decisions. And a lot of that was letting the narrator be who she is without signposts toward the past or the future. I don’t think the story is powerful if you’re like, “here’s why I am the way I am.”

That segues nicely into another question I have which is, the line you guys are navigating between — I think there must be such a delicate balance between this subtlety/ humor/ challenging life story balance, and a certain necessary amount of emotion and vulnerability — obviously vulnerability has gotten to be such annoying word at this point, but it’s essential — a degree of humanness, and ceasing to be cool, or ceasing to be sexy and controlled.

Right.

And I wonder how you navigate that as an editor. Because I get really frustrated when things go too far in the satirical zone but — I’m just wondering how you navigate that.

How do you navigate the balance between revelation and honesty in service of the story versus revelation and honesty as a gesture of vulnerability — I feel like there’s a sense in which people are selling themselves out. This emotion is only here for consumption, it’s almost shock value, in a sense. And I think it comes back to — is it in service to the story, is it in service to the character? Or is it in service of some kind of reaction that you’re trying to evoke? I think my answer to any sort of question is like, cutting to the bone.

That’s powerful. Can you talk a little bit more about your relationship to finding writers who do not come from a position of privilege?

Yes. I’m trying to think about how this works out in practice. Because one of the ways that we primarily find stuff is still via referral. So but we do have this background network of sixty or so people whose work we have celebrated in the past. And I think that another important component of this is being willing to do the work with material that doesn’t come in perfect. And this isn’t a direct comment to anyone who is currently on our list. But I think one of the things that everyone who’s involved in publishing can do some work with is being more open to stuff that doesn’t look the way you think it “should” look. This is more of a problem in mainstream publishing of how much time and effort and negotiation and energy am I going to have to spend to get my company on board with something that doesn’t look like all of our previous successes look like. How am I going to account for the fact that this is going to need a year edit instead of a six month edit. Everything comes down to money. So I think one of the things that we’re willing to do is to see something that’s still very new and very early and be like, “yeah, we can work with this.” Or see something that doesn’t — people need all kinds of support right? So support for young writers who look different or whose work looks different from what is in the establishment is really really not there. So that’s what we’re trying to do.

There was a really great quote in one of the interviews, I think it’s a Brooklyn Magazine one, from Caroline Casey [the Coffeehouse managing editor]. She says that, “as a publisher we prefer a messy and ambitious book to a cautious and extremely competent one.” And maybe that is part of what they’re looking for with you guys? To seek out that voice.

Yes. That’s definitely what they’re looking for from us and that’s been what we’ve always been interested in so it’s the perfect match. But we’ve heard the same stories for hundreds of years, we’ve been taught them in school, we’ve read them in the New Yorker and Harper’s, and we’ve been taught how to write them. I’m not interested in that anymore.

So what does that look like for you, in terms of your own learning curve, which is such—as a teacher I know it’s a challenge to figure what the author is trying to do, and adjust your vision to that. I would imagine that would look different every time.

It has to. Everyone’s trying to do something different, right?

So have you had any epiphanies in terms of moving to meet an author from where they’re coming from while guiding them? Moving out of your own taste?

One of the things that I had to deal with is not the picture that I’m trying to paint but… it’s ok for me not to know. It’s ok for me not to get it. It’s not for me. Some of this work is not going to be for me but it’s for someone. And not letting my… not trying to make it for me when it’s not. You know? But that’s easier said than done. But the authors and subjects — at OUP [Oxford University Press, Ruth’s day job] we have this really awful annoying expression, the “subject matter expert,” it’s like, I’m the subject matter expert in this really horrible computer program. But the author is the subject matter expert of their book. And my job is to help them be that and not make it my creative expertise.

Is there anything else that—

I do want to, Emily and I have always looked to Autostraddle as a model of what we want to do and a community that we want to build so the fact that this may or may not appear there is super gratifying. We’re big fans of Autostraddle and we always have been.

Well. I love you, because you’re my friend, so obviously it’s mutual from my point of view, but from what I’ve witnessed from Autostraddle that’s a very mutual feeling. And also, another thing, I’m curious to see what direction your own writing is going to go into. You write this newsletter which has this wonderful balance of personal narrative and pop cultural analysis and it’s really entertaining. And you went to school for fiction. I’m just wondering.

I often wonder these same things. I had this idea that any writing that I do has to be Art with a capital A otherwise it would not be worth doing. And that’s hugely limiting, for someone with perfectionistic tendencies, which most writers do, that means you’re probably not going to write, ever. If your bar for yourself is that it has to be art, that’s a pretty high bar. But I gave myself permission a year ago to start writing things for money. And this is not going to change, it’s not going to set the world on fire, it’s not going to be the best thing I’ve ever done, but I’m going to get paid $500 for it, so I’m going to do it! And that has been really freeing. And I’ve been focusing on that kind of writing more recently. Like that Refinery 29 essay that I was writing while I was in Tucson was really fun! I’m not going to anthologize it but—

It keeps you moving.

Yeah. Not everything has to be great. As a working writer I think that’s something that’s important to keep in mind because otherwise we’ll never do shit. Obviously at some point I’d like to do something great but. I did go to school for fiction but I’ve been more and more realizing that that’s not where my gift is, inasmuch as I have one. I don’t want to rule anything out. But I’d like to put together a collection of essays myself. It just remains to be seen when that’s going to happen. But I’m crippled by insider knowledge [laughs]. Because I’m like “what is my theme?” I think my standards for myself are ridiculous.

And it sounds like you’re in the process of softening them slowly.

Yeah. I also have this thing of thinking that no one gives a shit what I have to say. Which is another huge writer thing to overcome. Sitting alone with your computer and thinking, “who the fuck cares what I write right now.”

Which definitely feels like a gendered problem.

If I saw my writing career through the eyes of a mediocre white man I’d be, like, that dude would be fucking high on himself constantly.

Can we have some names you’re reading right now?

I have The Sympathizer [Viet Thanh Nguyen], the Pulitzer Prize winner from last year. I’ve got Jessa Crispin’s work The Dead Ladies Project. I bought a bunch of Claudia Rankine at AWP that I’ve been meaning to read ever since. I have Maryse Holder’s Letters from Mexico. What else is down there. I just read The Mothers by Brit Bennett, which I liked a lot.

Do you have a distinction between what you read for pleasure and what you read for work? Or is it completely the same bucket?

There is a lot of overlap, for sure. It’s very rare that I read something by a dude, for example. In the summer I’ll pick up the literary blockbusters. I still enjoy myself a literary blockbuster. I read this book called The Assistants [Camille Perri], which is about assistants at a media company that gain the expense system to pay off their student loans, which I thought was extremely well done and funny. So that’s my fun reading. When I go on vacation with my family I’m planning on taking the last two Neapolitan novels [Elena Ferrante]. So that’s going to be my vacation reading. Have you read them?

I got My Brilliant Friend, and I think I just haven’t sat with it enough to get over the hump that I have for all novels.

It’s, there’s a hump situation there. But when you get over it it’s very rewarding.

I have a very important question from one of my editors [Rachel]. Do you use the curry emoji in order to signify your last name? Curry signing off? Etc.?

I didn’t know there was a curry emoji until now, [Laughs]. Does that answer your question? I generally ignore the food emojis. The heart eyes one, though, I use that one a lot.