On May 22nd, Irish citizens will vote on changing the Constitution to allow anyone to marry regardless of their gender. You might not be aware of the Referendum if you’re living outside of Ireland, but here on this tiny green island, the fight for and against marriage equality is foremost in the national conversation. It’s a conversation you may have heard before, but it’s marked by a monumental first — the ability of a people to directly establish marriage equality in their country’s constitution — and peppered with any number of nuances that make this a different right than the ones I’m familiar with from American-centered media as an American now living in Ireland.

Ireland is undeniably Catholic in its veins, even if fewer than 1 in 5 Catholics attend mass on a Sunday in Dublin. Sure, you can’t throw a stick on this rock without hitting a statue of Mary or any number of favorite saints, but the landscape of altars and outstretched arms is not just for show. The Church has always had a strong influence over the Irish state, which accounts for its continuing conservativism on issues like abortion and birth control. Abortion on demand remains illegal in the Republic. Sales of birth control were banned until 1978, at which point they became available with a prescription. You can now buy condoms in your local pharmacy without much fanfare, but most generations of Irish have grown up without formal sex education and a heap of societal repression.

Marriage is one of the foundational values of Catholicism, and thus has historically held a high standing in the Irish state. Divorce was illegal in Ireland until 1996, outlasting the lift on criminalization of sodomy by three years. In Irish society, marriage still carries a great deal of importance in the legal sense, as it is a Constitutional protection of another value at the heart of Ireland: family. It was unquestionably huge when Ireland passed civil partnerships as a way for non-heterosexual couples to have some legal bindings, but it was not a permanent solution. Civil partnerships are not Constitutionally protected, and they do not offer the legal protections to the family that marriages do — I should know, as I’m in one. It seems that the acceptance of queerness in Ireland, particularly our relationships and family-building, was always going to come down to the issue of marriage. It might just be, as they say, an Irish solution to an Irish problem.

Ireland is a small country, with a total population smaller than the city of Philadelphia. Size is one of the most important factors in the Referendum – literally everywhere the country is talking, in small conversations and big conversations, about marriage equality. This is a conversation that can be overheard on the bus, at the butcher’s, between your two elderly neighbours or strangers in the Tesco. Every person in the country is aware of this issue, and feels a responsibility to develop an opinion on it. It has become important in a way I could never imagine it becoming important in American terms. In the weeks leading up to the Referendum, business windows have sprouted rainbow flags and supportive posters, every lamppost in Dublin is encouraging one side or both, every third lapel on the street sports a Yes badge. You cannot escape the topic or its eager debaters if you try, a fact both exhilirating and exhausting in the last days coming up to the vote.

It’s true that Irish society has changed rapidly in the past few decades, at a rate faster than almost every other European country. One factor responsible for this change was sudden economic growth – the infamous, and admittedly fleeting, Celtic Tiger. The speedy transformation from one of Europe’s most socially conservative societies to a country liberated by new values and new priorities is largely responsible for the push towards marriage equality, but it does not guarantee a Yes at the polls. Youth voters are notorious for big talk and small turnout. Allyship is a tenuous concept, although I have never in my life seen the kind of passionate and caring allies I have witnessed stepping up for this fight. As the fight has become increasingly personal and significantly louder, it’s been helpful to have people who are willing to stand up and be a buffer so that LGBTQ folks can do some very needed self-care.

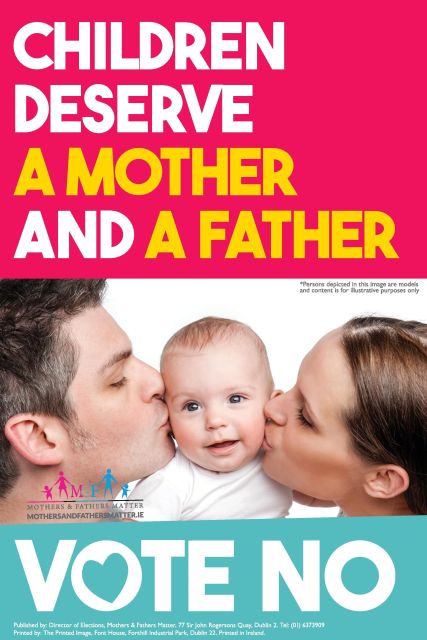

That Catholicism I mentioned earlier? It’s a sneaky reason why the opposition to gay marriage rings so differently here than it does in the States. Americans may be used to Old Testament-fueled rants against sodomy, all that brimstone and hellfire and God Hates You Know Whos, but the Irish organizations against marriage equality are less likely to defend themselves with Bible verses than they are to swear they are defending the family itself. Yes, it’s ‘Won’t someone think of the children?’ that dominates the dialogue here, that Irish Catholic family that is so dear to the national heart. I hate to give attention to their undeniable bullshit, but I don’t have room in my heart to let someone claim that hate speech is a valuable component of democracy. Knowing that family and children are so important to the heart of Irish culture, organizations such as the Iona Institute and Mothers and Fathers Matter are blowing a great deal of smoke about surrogacy, an issue that has nothing to do with the Referendum. They’re also throwing up thousands of posters of smiling happy stock photo families, reminding the public in heart-accented typography that children deserve a mother and a father, that two men can never replace a mother’s love, and that a vote for marriage equality is a vote against the rights of children. Never mind, of course, the rights of a child who will not be legally protected when her mothers are unable to marry, and their civil partnership abolished by a future conservative overhaul. Never mind the rights of queer children growing up all over Ireland, seeing these debates about their ability to love, their place in a family, and wondering how their homes and communities will think of them.

It’s true that not every gay person is looking to get married, and a change in wording to the Irish Constitution will not cure Ireland of all instances of homophobia. It feels ridiculous that I need to state that disclaimer – marriage equality will not solve all of our community’s problems – but I do. If you’re like me, you may be used to an American-centered conversation around marriage equality that feels stifling, divisive, and often erasive of other queer experiences and needs. It would be easy to take this perspective and apply it to the Irish Referendum, but to do so would be to ignore the complicated differences between the two situations. Marriage equality in the United States is decided on different terms, represents a different political situation, and holds a different value than it does in Ireland. I was not always in agreement with the American campaigns for marriage equality, but I would be wrong to apply the situation of my home country to the one in Ireland.

More than anything, I am personally involved. In the United States, by and large political representatives are the ones actually voting for marriage equality, on whatever terms it has arrived in the legislative houses. Before I reach those representatives, they are met by any number of financially gifted lobbyists and interest groups, some of whom share my orientation but not necessarily my values or my experiences. Here in Ireland, my neighbour will decide if I can marry and have legal protection for my children. My colleague will decide, and so will my doctor and my grocer and the people I pass on my way home. I cannot vote because I am not yet a citizen, but I can speak directly to the people making that decision. And hopefully, when and if the time comes, I can thank them for making the rest of my life safer and much more possible.

Comments

Kate, if it makes you feel any better, the parents in that photo on the poster you mentioned seeing like 3000 times on every light pole in Dublin have said that they absolutely support Marriage Equality. The photo is a stock image of them and they had no idea it would be used like that. Small victories – they were horrified that their photo is being used on the ‘No’ posters. Also, I’m coming down from the North to canvass on Friday. Can’t WAIT to win this!!

a friend of mine bought another stock photo of the family and made a “corrected” version: https://twitter.com/forbairt/status/596237139060334592/photo/1

he’s gutted he can’t make it home to vote (lives in France), so feel free to print one off and slap it on a light pole for him :p

also, if someone can send me one (or three) of those yes equality in gaelic cards I would be forever grateful? well, if it passes. no use having that to decorate my eventual office if it’s just a bitter memory!

It so bizarre that so many people in the world may not know that this referendum campaign is raging on lamp posts and doorsteps and every possible Irish media platform, when right now the referendum IS our world. Almost as bizarre as going door to door asking people to vote on your rights, and being greeted by a minority of smiling faces politely but firmly telling you they’ll be voting against them. Or as bizarre as the fact that results day coincides with Eurovision day (divine queer intervention or the government having a laugh??).

I find it bizarre that here next door in England it’s not being covered more to be honest.

Same! I’ve been following the news more since the run-up to the UK general election and hadn’t heard anything about this until now.

Good luck, Ireland! I’m a Brit but come from an Irish Catholic family (the vast majority of whom still live in Dublin) and I’ll be keeping everything crossed for Ireland on Friday, and sending positive thoughts to all the Irish Straddlers. I’m not sure how I feel about the fact that it’s being put to a popular vote, but I it would be pretty wonderful to see a whole country decide in favour of equality. I hope it goes the right way.

It’s also important for American readers to know that homophobic orgs from the US likely tried to fund campaigns to vote no (although doing something like this official is illegal under Irish law). People have this image of US orgs funding homophobia in a handful of African countries, but this actually happens virtually everywhere. There’s American money at the bottom of well organized homophobia almost everywhere.

Someone make an infographic!

Its so cool to see Autostraddle covering this!!! Honestly, its crazy because none of my friends at home (in the US) who are usually on the ball with this kind of stuff have even mentioned it to me. I have to admit, it is a really bizarre time to be in Ireland, and seeing the “No” posters everywhere is really messing with my head lately. I get excited every time I see a “Yes” poster and disappointed then when the next lamppost has a “No” one on it, especially since the “No” ones are such bullshit. And its insane to be talking about marriage equality with the older Irish ladies I work with and to hear my neighbors chatting about it at our cafe…it’s something so personal to me and people talk about it so nonchalantly. I will definitely be relieved when the vote is over.

Me too. I actually stopped dead in my tracks when I saw my first No poster. I’d seen them all online before, but I was surprised at how much it stung to see one in person.

I’m exhausted at this stage. I can’t express how much a yes result will mean to me, and conversely, now badly a no result will make me feel. I can’t wait for Saturday for the count to finish, but I’m terrified too.

This is one reason I’m happy to have courts decide. Going through a public vote on your rights is such an emotional, upsetting experience. I’d even go so far as to say traumatic, given some of the homophobia that such campaigns can bring to the forefront from the most active No campaigners to coming face to face with those who simply say “No, I oppose your rights” quietly and calmly as though commenting on the weather.

The French vote was through the legislature, not referendum, but it still sparked such a mental homophobic backlash it still stings 2 years later.

At least there are the supporters and their love, kindness and determination to provide some balance.

Sending positive thoughts to you all and hoping for a cause to celebrate next week.

To be honest, I initially wanted it to be done through legislation. After all, the Irish constitution does not define marriage, nor does it specify what genders can/cannot marry. It is only legal cases after the fact that have put that interpretation on it.

However, it is now clear that the only way for true equality in Ireland is by referendum. In Ireland there is special constitutional protection given to the family. This has wide-ranging implications, from possession and protection of your home (a “family home” has a special place in Irish law, but a “shared home”, which civil partners have, does not), to how you can be treated by state agencies (a married couple may not be disadvantaged in any dealings with the state by their marital status compared to a single person or unmarried couple, but civil partners have no such guarantees).

There is no constitutional protection for civil partnerships in Ireland. This means that in the future a conservative government could dissolve the option of civil partnership without consulting the people.

So while it’s an undoubtedly tough process (and I really feel for anyone out there who is only coming to terms with their own sexuality), if the referendum passes it gives us the most security for our families, whether we have children or not, and has the added bonus that we know that most people who went out to vote are saying “It’s okay to be gay”.

Oh, and I should have mentioned that all changes to the Irish constitution, no matter how big or small, must be ratified by the people. So a referendum is the only way to get this amendment made.

I’m really hoping all the allies turn out and don’t stay home. Nudge theory suggests that people are most likely to take action if they think they are going to suffer a loss. Sadly for the homophobes that equates to losing the privilege of telling everyone their relationships are superior. That will bring them out in droves.

I also fear the silent nos who have already made their minds up but don’t want to be hectored. We all saw what happened in the UK earlier this month. No one saw the Tories getting a majority Come on yeses especially the young uns. Get voting come Friday.

As a sidenote: Switzerland was the first nation that passed a same-sex union law by referendum (2007). Sadly it wasn’t for marriage equality, it’s called “registered partnership”. No joint adoption is allowed. Wanna know the ironic part? As a single person you’re allowed to adopt but as soon as you enter a registered partnership you’re not anymore…

Anyway, hoping it will pass in Ireland! Good luck from Switzerland!!

It’s been what, more than 14 years since the Netherlands legalized equal marriage?

The country is still on the map, it wasn’t sucked by a big black hole after the “destruction” of the traditional family and kids living with 2 moms or 2 dads.

They even had those “horrible” coffe shops… and are still on the map.

Come on, Ireland. I think this says it all…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PCZWv5U5wJ4

I love that you covered this and I love that you recognised and mentioned the differences between the U.S. and Ireland, thankyou for that. I was discussing the political differences between America and Britain just the other day with my friend’s American fiancée, and these are different yet again (not to mention the regional differences within our tiny island and a bit). I think it’s important to recognise, and discuss these differences which are often assumed not to be, possibly due to common language.

I hope the good folks of Eire, including my long lost relatives, vote yes. Best of luck Ireland!

I was in Dublin last month and took this photo:

I’m rooting for you guys (and for that cute waitress I flirted with at Nando’s)!

I’m feeling hopeful :)

Arghdsfuifjgh!

Whatever ¬¬

Here’s the image url: https://40.media.tumblr.com/d6dffcc6e066f0f3cbe17b3eef8f369f/tumblr_nmjqtfzKNi1uoxbn5o1_540.jpg

Good Luck with the vote Ireland. Australia will be watching hopefully too. There is considerable support for a Referendum here too.

Sending all of the good vibes yall’s way on the 22nd!! Hopefully Germany won’t be far behind.

I remember this happening. I was living in Ireland at that time (going to high school, got my leaving cert that year, if you care to know). Pope John Paul 1 (the one who was pope for 33 days) said contraceptives were “OK if used in moderation”. So Ireland decriminalized possession of them (in the beginning, one needed a prescription from a marriage counselor – a regular doctor would not do). His remark – being such a fundamental deviation from tradition theological condemnation of contraceptives – were so surprising that when he died suddenly, rumors were that the Cardinals offed him.

Ireland has come a long way since I lived there. I am very impressed. Good luck with the upcoming vote.

I’m so so so nervous. I really hope it goes through. I’m trying not to think of the devastation we’ll feel if it’s rejected.

I’m surprised it isn’t a bigger deal worldwide. I know Ireland is really small – smaller than most cities in terms of population – but this is the first time EVER that the ordinary citizens of an entire country have had the opportunity to vote for extending marriage equality to their peers.

If you’re interested, the wording of the amendment is so so simple: “Marriage may be contracted in accordance with law by two persons without distinction as to their sex.” <3

thanks so much for writing this article kate and letting the good people of autostraddle know what’s going on in our little corner of the world.

thanks so much for this thoughtful overview, kate. it’s always great to hear your voice…

Today’s the big day. I’m nearly in tears just thinking of either outcome, and I am not even Irish American. :p Sending all the good thoughts and love up to you all.

Thanks! I’m so nervous. I can’t focus. I’m all shaky. But we can do this, I know we can!

The outpouring of love and support from straight allies has been nothing short of beautiful. We’re really all in this together.

When will we know the final results?? I don’t know why I’m so nervous xD

It’s estimated to be tomorrow evening, around 5pm-ish. Voting is open until 10pm tonight and counting won’t start until the morning. Keeping us in suspense!

O_O I don’t know if I’ll be able to survive that long… I hope we’ll have a “yes” to celebrate during Eurovision

Thanks for the info!

Me too! It would make it the super gayest weekend ever!

LOVE the Yotsuba icon, by the way

Thank you! I think it might be my favourite series of all time. It’s so joyous :)

Want to cheer yourself up? Check out the #hometovote tag on Twitter.

Irish people cannot vote unless they are physically in the country (except for diplomats and the Defence Forces), so lots of people have taken time off work and spent money on flights and ferries to come home and make their voices heard. It’s beautiful.

Early tallies are estimating a 2:1 victory in favour of marriage equality, with the major opposition group conceding defeat. Official results expected around 4pm GMT.

I am beyond excited! We are making history!