For being one of the oldest terms related to gender nonconformity on the books, the concept of ‘tomboy’ is surprisingly slippery. Cara did a deep dive on it five years ago, finding that while it had initially described “boyish” boisterous behavior in general, it later came to signify boyish behavior as practiced by girls, specifically. Culturally, it’s come to speak to behavior — “tomboys, when they sat still long enough to be described, were pinned as “wild and romping,” “ramping, frolicsome, and rude,” and (my personal favorite) “a girle or wench who leaps up and down like a boy” — and as a subset of that, presentation and dress.

Part of the reason why ‘tomboy’ is so hard to pin down is that in many ways, especially as linked to a sort of oncoming adolescence, is that it felt less in lived experience like a discrete identity and more like a refusal to comply. Cara writes that “Charlotte Perkins Gilman called tomboys “the most normal girl… a healthy young creature, who is human through and through; not feminine till it is time to be.” The idea put forth, then, is that a tomboy is a kid who gets to be a kid instead of a ~girl~ — something which in practice often looks to adults like a girl rejecting femininity or being aggressively ‘boyish.’ Figuring out how to “do” one’s assigned gender is a part of growing up for pretty much everyone, but in both fiction and real life, tomboys get the sense that everyone else is having a much easier time navigating it. In “Reading Like a Tomboy,” Miranda Pennington talks about reading books with female protagonists in part to figure out “how to “girl” properly,” and finding some hope in the characters who also didn’t quite have a handle on this at the same time as she clung to the characters who did, desperate for instruction.

Reading was a great tomboy activity — it didn’t require groups of friends, and was a way to indulge in unrealistically ambitious tomboy hobbies (sword fighting! space exploration!) from the comfort of the backseat of a car. Maybe for this reason I remember, somehow, a body of literature rich in girls and women who loved doing things with their hands and having mildly ill-advised adventures, and who didn’t hate dresses and hair barrettes so much as feel a baffled disinterest. Upon trying to unearth that literature, though, it turned out to in fact be very spotty! So many of the texts I thought I remembered as tomboy lit now felt more like just stories of girls navigating outsider status or sexism, and that I had maybe projected onto more than I realized. Others that were more explicitly about non-normative girlhood now read more as being explicitly about queerness, masculinity or butchness — experiences which are not at all mutually exclusive with tomboyhood, but which seem to imply a certain active identification rather than the borderless, culturally undefined space for possibility that feels like tomboyishness.

Cara describes in her investigation “a ‘12-point tomboyism index’ that included such items as “engaging in loud or boisterous play with others” and “participating in traditionally male sports.” Meant to describe real children, it’s nonetheless a suggestion toward how we might recognize tomboyhood in its various iterations in books — characters are sometimes intimated to be queer or lack an appropriate interest in boys, but not always; they often reject dresses, makeup, bows or the like but might just be less enthusiastic about them than other girls, or less adept; they might have an interest in physical activity or “boys’ hobbies.” They’re often young; the question of what happens to tomboys when they grow up is, culturally, a difficult one. Whereas female protagonists are usually “feisty” or “spunky” — protagonists are always supposed to feel special and different — tomboys in books as in life are often read by others as “difficult,” “surly,” “improper,” or otherwise actually badly behaved.

In the end, the definitely incomplete and scattershot survey of tomboys in literature ends up reaching in a few different directions — older works from the early to mid 1900s which still resonate today because difficulty with “doing girl” were a primary conflict (maybe because in a pre-girl-power world the importance of doing girl correctly was a more explicit expectation), fantasy and sci fi where spunky girls pick up swords and lightsabers, and the more contemporary depictions, with some fictional explorations and the burgeoning genre of memoir on the topic. This isn’t even getting into nonfiction studies on the topic, like Tomboys: A Literary and Cultural History, Tomboys!: Tales of Dyke Derring-Do, American Tomboys 1850-1915, or Sissies and Tomboys: Gender Nonconformity and Homosexual Childhoods. (Also without getting into the category of straight “tomboy” romance fiction, which seems fascinating.)

This list is very incomplete and highly subjective! But seems like it speaks to a persistent need; in researching any writing about tomboyhood, the interest in the literary figure keeps recurring, in Reading Like a Tomboy, The Tomboy in Literature, and concern about the Death of the Literary Tomboy. It’s a need that speaks to wanting to see ourselves as children, but also possible futures for ourselves as adults; as Miranda Pennington writes:

“While there was plenty I could learn from Anne Shirley or Harriet the Spy, I always longed to read about an actual tomboy like me – no long braids, no puffed sleeves, no growing up into a swan after an ugly duckling childhood. Finding a story like that would have given me one way to understand and explain who I was, and perhaps spared me a great deal of trouble.”

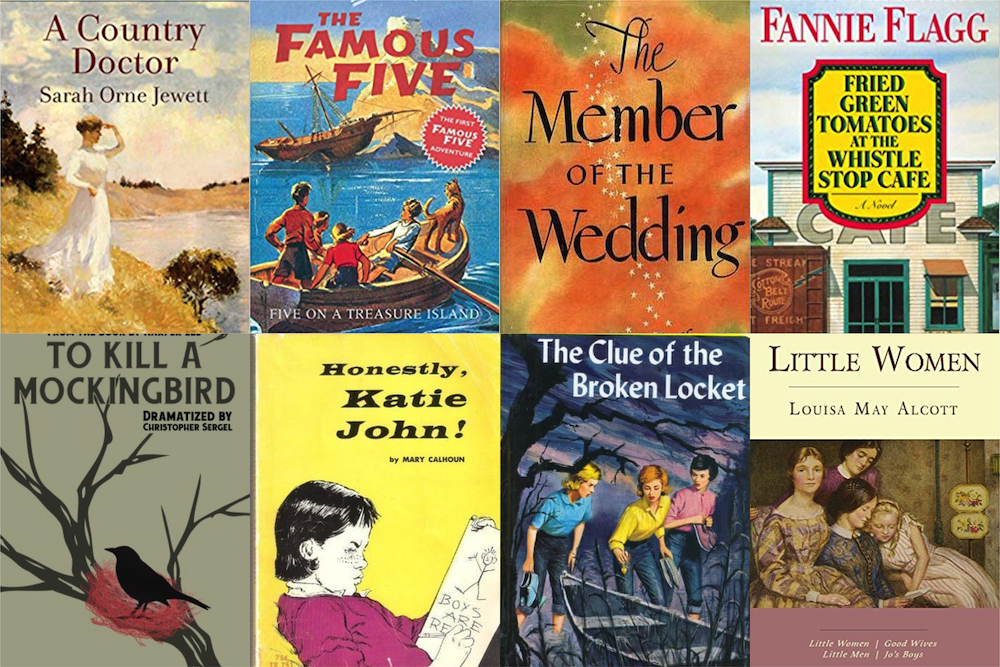

Foundational Tomboys

To Kill a Mockingbird: Jean Louise “Scout” Finch tries to navigate the adult world of racism and moral failings, while her Aunt Alexandra begs her to wear a dress and “act like a lady.”

A Country Doctor: As per Cara’s description, Nan Prince “got the tomboy stamp by putting [her career] ahead of (or firmly adjacent to) [her] domestic lives” when she pursues becoming a doctor.

Honestly Katie John: In which Katie John takes on a leadership role in the Boy-Haters Club.

Little Women: Jo March famously exclaims “It’s bad enough to be a girl, any-way, when I like boy’s games, and work, and manners. I can’t get over my disappointment in not being a boy.” (Check out this entire academic paper on Jo as literary tomboy!)

Tomboy: “Gabby strongly resists her parents’ efforts to persuade her that she must give up her tomboyish ways and turn into a proper young lady.”

The Member of the Wedding: In this classic from Southern Gothic master Carson McCullers, isolated misfit Frankie wants people to be able to “change back and forth from boys to girls” and struggles to find a place in her family and community — Frankie goes on to be cited in queer and gender theory texts as a crucial tomboy figure, including Female Masculinity.

Nancy Drew Series: With her classic tomboy name, George Fayne is “athletic” and “less than proper;” she consistently has boyfriends and is shown to wear dresses and care about her appearance, although arguably less interested in “fussy” styles than her friends Nancy and Bess.

Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Cafe: A rare tomboy character who we see in adulthood and also gets to be explicitly queer (at least in the book), Idgie Threadgoode is a blueprint for both tomboy and lesbians in literature, a rare feat.

Five on a Treasure Island: One of the earliest entries and an actual children’s book, we meet “a surly, difficult girl, who tries hard to live like a boy and only answers to the name George.”

Girls with Swords

Song of the Lioness Series: The light and hope of so many baby queer readers, Alanna wanted to be a knight so bad that she pretended to be a boy for years to train and become one, and even after she was discovered, was so good at knighting that she got to be the King’s Champion.

Protector of the Small: Also dying to become a knight, Kel lives in a post-Alanna world and can become one without impersonating a boy, which means she has the very relatable tomboy experience of being isolated and ostracized when she pursues her dream.

Of Fire and Stars: Although canonical LGBT rep in YA is (thankfully) no longer scarce, and there are plenty of girls who can use a sword or a bow and arrow, Mare is a welcome example of a princess who prefers wearing leggings and riding horses while acting “surly.”

Contemporary Tomboys

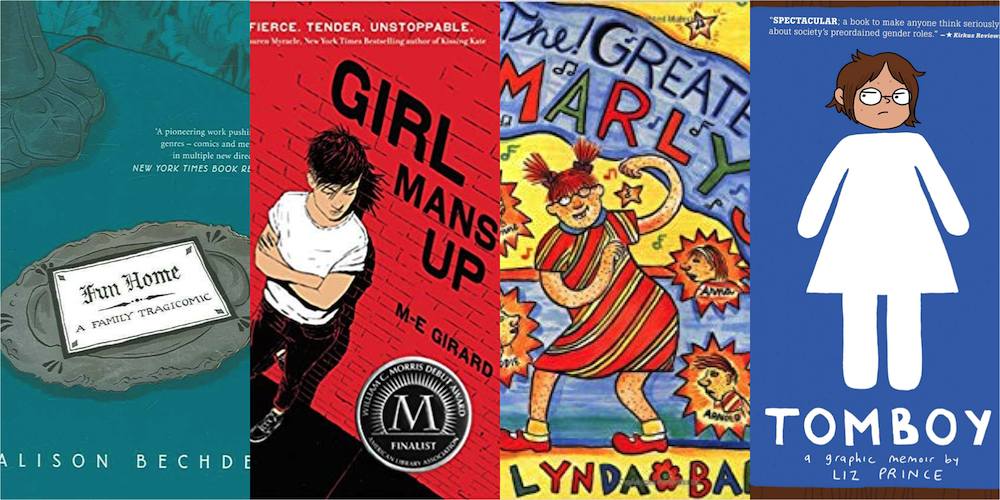

Marlys: Eight-year-old Marlys is the star of Lynda Barry’s classic Ernie Pook’s Comeek, and while Barry doesn’t necessarily describe her as a tomboy, she’s become a bespectacled, boisterous icon.

TOMBOY: An autobiographical graphic novel about Liz Prince’s “ever-evolving struggles and wishes regarding what it means to ‘be a girl.’”

Tomboy Survival Guide: Ivan Coyote’s account of “the pleasures and difficulties of growing up a tomboy in Canada’s Yukon, and how they learned to embrace their tomboy past while carving out a space for those of us who don’t fit neatly into boxes or identities or labels.”

Fun Home: Famously a memoir of Alison Bechdel’s relationship with her troubled, closeted father and her coming of age as a lesbian, Fun Home also chronicles her childhood as a kid who dreads wearing dresses and the feminine accessories that go with them.

Girl Mans Up: As Emma reviewed for us, Girl Mans Up is about gender nonconforming teen Pen, and “the language of our lived experience of moving through and within gender — inching, painfully slow, changeable, delightful, sexy, and made manifest in a thousand tiny ways.”

Please add to this admittedly incomplete listling in the comments! What are your favorite tomboy reads?

Comments

absolute musts are the European classics:

Pippi Longstocking, Ronia the Robber’s Daughter, Red Zora

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pippi_Longstocking

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ronia,_the_Robber%27s_Daughter

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Outsiders_of_Uskoken_Castle

I loved Ronia the Robber’s daughter. I had forgotten about that book! Thanks!

Pippi Longstocking was such a role-model to me in the early 70s.

And I’m glad I was a kid then, because I truly believe it was possibly the less-gender-restrictive time (in terms of toys and clothing) to be a child. Not that I didn’t get pressured into dresses etc on special occasions.

The True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle, Harriet the Spy, and Ms Teeny-Wonderful. I also latched onto secondary characters in other Martyn Godfrey books like Can You Teach Me to Pick My Nose and Please Remove Your Elbow From My Ear (the 90s were really a time).

Ronia Robber’s Daughter was so good!!! But I hated that she ended up in a relationship with the boy. When I was a kid I thought of them as siblings so when it got romantic I was very creeped out

I loved Pippi so much! Ah, the many nights I spent trying to sleep upside-down in the bed like she did, only to overheat and give up after ten minutes.

I love this!

LOVE THIS SO MUCH

Did anyone else read Just Plain Maggie? It was this super old book about a girl named Maggie who went to summer camp, and it was my very favorite thing in the whole world for QUITE AWHILE.

ramona quimby! i haven’t read the books in ages but as i recall she was p tomboyish

I immediately thought of Ramona Quimby! I’m so glad other people saw her as a tomboy because I super identified with her that way.

Yes!!

I definitely think of Ramona Quimby as a tomboy. Or maybe tomboy femme. As a kid I really identified with Ramona’s awkwardness and tendency to make mistakes, lol.

Here are the “tomboy index” items, if anyone is interested:

On a scale of Tomboyism, how would you rate yourself as a child?” (7-point scale, 1 === not at all a tomboy, 7 === very much a tomboy) indicating high concurrent validity. The items were as follows (all were preceded by “Before age 12, I …”): (1) preferred shorts/jeans to dresses; (2) preferred traditional boys’ toys (e.g., guns, matchbox cars) over girls’ toys (e.g., dolls); (3) resembled a boy in appearance; (4) wished I was a boy; (5) preferred traditionally boys’ activities (e.g., climbing trees, playing army) over traditionally girls’ activities (e.g., ballet, playing dressup); (6) had girl friends that were tomboys; (7) participated in traditionally male sports (e.g., football, baseball, basketball) with boys; (8) was loud or boisterous in my play with others; (9) preferred playing with boys over girls; (10) used traditionally girls’ toys in traditional boys’ activities (e.g., Barbie driving a Tonka truck); (11) engaged in rough and tumble play; (12) played with many different peer groups (e.g., tom-boys, non-tomboys, boys)

I went looking for it because I’d score pretty low on the two items mentioned in this article! (not sporty, and did not like play-fighting (too much real crap at home))

Ironically, I’d score low on item 10 as well, because I never, ever, ever played with girls’ toys, in any fashion.

Full article for the study is here: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/76f7/10c904fffeb2bae8b1ca2af23320efb291f5.pdf

Thanks for pulling this out. The only one that doesn’t resonate is wanting to be a boy. Luckily, I grew up in a “redneck” culture and family in the south, so one thing they did support was my tomboyism and nature love. I never felt that I had a need to be a boy except maybe jealous that they were never forced to wear scratchy and dumb lace for Easter Sunday…and also peeing in nature was much easier for them, lol.

Yes, me too. Forgot that one.

I totally never wanted to be a boy, and never much liked them either. Despite being *extremely* tomboy in behaviour and not liking girls’ standard play activities (skipping, etc) – I was a lonely child, heh.

That’s really interesting. My score was 3.25.

I currently id as tomboy femme and I think I always had tomboy femme tendencies.

Cynthia Voigt, Dicey’s Song (and Homecoming I think?) – been years since I read them but my remaining hazy image of Dicey is fairly tomboyish.

The Homecoming books by Cynthia Voigt (including Dicey’s song) were central to my tomboyism.

It’s been a while but I feel like Caddie Woodlawn is somewhere on the scale

Yes! I remember enjoying her as a character.

I loved Caddie Woodlawn! I never much cared for the Little House books but I loved Caddie.

She’s one of the first ones that came to mind for me. The ending always seemed so disappointing to me – like she was tamed or something by doing proper girl things

Caddie Woodlawn is a pioneer redhead tomboy that winds up ruining a fancy dinner with a visiting pastor in one of the book’s first scenes. She has endless adventures throughout the book. I haven’t re-read it recently so I don’t know how it treats issues like feminism, colonialism, respect for indigenous people. or other things that. Young me saw myself in Caddie like few other heroines, though.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caddie_Woodlawn

My ex-gf’s niece went to an elementary school named after Caddie Woodlawn near Eau Claire, Wisconsin

Tomboys in kidlit were so important to me growing up, and now I want to go back through all my books from childhood and gush about my favorites. ☺️

I feel so seen. Thank you for breaking down so eloquently why I have always strongly identified with being a tomboy yet felt an underlying wrongness about the word and connotation. Also, books!

Calpurnia Tate anyone? <3

I don't know where her story goes in the sequels, but I love how her grandfather encourages her being outdoors and tapping into her scientific brain. The story really normalizes her experience by using the grandfather relationship. He also balks the traditional roles of the late 1800's.

Amazon:

Calpurnia Virginia Tate is eleven years old in 1899 when she wonders why the yellow grasshoppers in her Texas backyard are so much bigger than the green ones. With a little help from her notoriously cantankerous grandfather, an avid naturalist, she figures out that the green grasshoppers are easier to see against the yellow grass, so they are eaten before they can get any larger. As Callie explores the natural world around her, she develops a close relationship with her grandfather, navigates the dangers of living with six brothers, and comes up against just what it means to be a girl at the turn of the century.

part of my queer origin story is that my best friend and I were locked in basically a death match of auditions/call backs to play Frankie in my high school’s production of the stage version of The Member Of The Wedding (she got the part and I did props!!!!!)

When I started my period my mom took me to buy a book (in celebration, I guess?) and I 100% got Tamora Pierce. Those books really spoke to me, except for the weird pattern of the tomboy protagonist always ending up romantically with the older male mentor, which kinda squicks me out in hindsight

It goes all the way back to Jo March getting married to Prof Bhaer. Urgghhh. Anne McCaffrey got into it as well. Then again, her sexual relationships stuff was always a bit… fraught.

The trope is one I oddly related to, though? Because before I figured out I was queer, I would sometimes think about who I would marry. There was no way in hell I would want to marry some moronic horny boy my age.

But an older mature “professor” type who treated you with respect and might provide opportunities for you to learn about cool things? (And not too much sex? Not that I thought of it in those terms) Potentially bearable, maybe?

I finally figured it out in my mid-teens, thank god, but yeah, the trope wasn’t as off-putting to me then (40-ish years ago) as it would be now.

True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle I remember as involving an upper class girl who ends up out of money and cross dresses to become a cabin boy maybe? It was definitely the first time I’d seen cross dressing in a book I think.

Harriet the Spy!

Among YA: Always considered Lyra Belacqua a bit of a tomboy! (His Dark Materials books)

Though my favorite tomboy character is the book Jackaroo by Cynthia Voigt—she becomes a famed masked outlaw when the people need it!

Lyra Belacqua / Silvertongue is like, the platonic ideal of tomboy protagonist! The opening scenes of her running around the rooftops and back alleys of Oxford have been etched into my memory since I first read them in fourth grade.

I still have the copy of Jackaroo my grandparents gave me for Christmas one year. It was a surprisingly good gift from them. I haven’t talked to many people who read it, but it had a big impact on me

Did anyone else read the Sophie series by Dick King Smith (or was this only purchased for children named Sophie)? The books are were about a little British girl who wants to be a “Lady Farmer” and to that end collects snails and wildlife and a cat whose name is actually Tom, short for Tomboy. She has lots of (occasionally misdirected) aggression towards her femmey classmate Dawn and Dawn’s toy pony Twinkletoes and instead chooses to be best friends with her conformed spinster octogenarian “Aunt Al.” Per Wikipedia, she is “often described as wearing a faded blue jumper with her name written on it, jeans and red wellies, and her hair is often quoted as looking like she’s come through a hedge backwards.”

13/10 I use casual references to Tamora Pierce to confirm if a gal is my people.

18/10 baby me would have been delighted af that I grew up to be and also build a family with a lady knight who is very George and that we little house in the big woods our life.

cameron post CAMERON POST

How did I miss seeing this a couple of days ago? I’m so excited to see this list and these reflections on tomboys.

My dad read “Swallows and Amazons”to us when I was about 8 and Nancy Blackett is 100% my root.

It’s about 2 families of kids making adventures in boats in and around the lake District (in England) in between ww1 and ww2.

Least favourite is “Yosemite Tomboy” by Shirley Sargent because I found Jan relatable and then at the end of the book she was turned into a Yosemite lady. My older brother gave it to me to read and I was so furious and humiliated I a very protective person of books actually threw the book at something.

Adult me wonders if the ending was retconned against the author’s wishes by the publishing company or something.

Foundational tomboys for me were: Jo March of course, Anne of Green Gables (which I never actually read but which my cousin used to listen to on cassette when we went to her family’s cabin in Wisconsin. My cousin is a lesbian now), and maybe this is a stretch but Violet Baudelaire! She was never afraid to get her hands dirty or give up her hair ribbon for science. I also read SO much “girls crossdressing” fiction as a kid, so you know, all of those too. Charlotte Doyle, Protector of the Small, The Goose Girl by Shannon Hale (her other books never quite measured up in my mind), Girl in Blue by Ann Rinaldi which was my fav historical fiction book for years because….the Civil War was just, you know, really interesting…

This remains the gayest fact about my childhood. I don’t know! I was just into strong kind girls who had to sensually bind their boobs for adventure! It’s fine!!