The first time I learned about street harassment, I was taught that only I could prevent it. This was about the same time that Smokey the Bear was telling me that only I could prevent forest fires and Captain Planet told me that the power was mine to save the Earth. The world was sure entrusting a lot to seven-year-old me.

The aforementioned logic about street harassment taught me that street harassers targeted only “sluts and whores.” This overwhelmingly male population that felt the need to humiliate women were never referred to harassers, assailants, or even bullies, but instead regarded as some sort of moral authority that reminded women when they were demeaning themselves. My job was simple: if I had the self-respect or dressed properly and carried myself with dignity, my friendly neighborhood Hemline Police and Cleavage Monitors would not have to encourage me to cover myself up with their lewd comments and unwarranted advances.

via Ms Magazine

My first incident with street harassment took place during a visit to the ultra-conservative Jamaican town my parents grew up in. I had entered the tumultuous, hormone-fueled pubescent era of my life, and my baby fat had begun migrating towards my hips and ass. On the day in question, I walked to a small corner shop with my cousins, and following the town’s standards of propriety, I was wearing a bright blue skirt that flowed almost to my ankles. I did not understand that I was being catcalled until my cousins pointed out the male attention. I was bewildered in part because I didn’t know why these men would want me to be interested in them, but mostly because I was following the “rules” by wearing a long skirt! One of my cousins explained to me that the color of my skirt made my butt fluorescent and implied that I should not wear such colorful clothing around my derriere if I don’t want to be hit on. Admittedly, there was a part of me that appreciated that puberty had my body interesting — plus, I hadn’t discovered that I was super gay yet — but I felt really ashamed of my failure to be modest. I went home and never wore that skirt again.

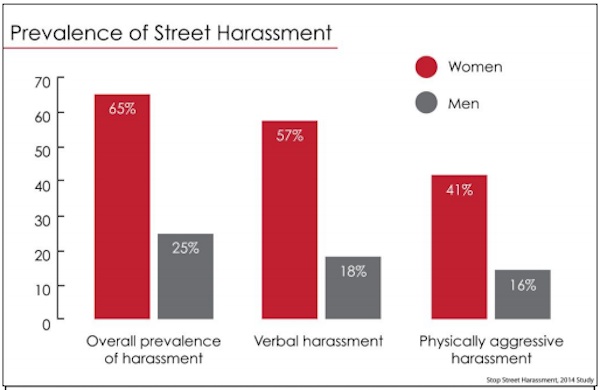

Ten years and countless obnoxious, absurd, often racist catcalls later, I fortunately have learned that street harassers are not trying to encourage me to dress with decorum, nor is it my fault if someone antagonizes me that way. Mostly, what I’ve learned is that I’m unfortunately not alone in this phenomenon. This year, Stop Street Harassment (SSH) commissioned a report wherein they found that out of the 2000 U.S. Americans studied, 65% of women surveyed had experienced street harassment. 23% of these women also said they hey had been touched sexually in these incidences of street harassment, twenty percent had been followed, and for 9% of participants, the harassers forced the women to do something sexual.

Interestingly, the SSH also studied LGBT-identified individuals. The SSH research has made me think about what it means for us queer women to be harassed on the streets. Although the SSH report suggests that there is not a significant statistical difference in what percentage of LGBT-identified women are harassed versus their heterosexual counterparts, I do think that street harassment impacts queer women differently. Street harassment is vile and unpardonable no matter the sexual orientation of the perpetrator or the target, and being attracted to men as a gender in no way means that one is inviting or justifying harassment. However, for LGBTQ-identified women, street harassment often demonstrates the additional violence of compulsory heterosexuality and heteronormativity.

What happens at this juncture of street harassment and compulsory heterosexuality? A higher percentage of LGBT-identified women in the survey reported experiencing daily harassment (7% of LGBT-identified women versus 1% of straight women), and I’m curious to know if researchers asked their subjects what happens in those moments of street harassment. The report does not detail the delegitimization of and attacks on our sexual orientations that these street harassers will use to suggest that we truly should be interested in them; the ways in which LGB women can be targeted not only on the basis of their disinterest in one particular man, but disinterest in men generally. When we have these conversations about street harassment, we don’t always talk about the unique experiences LGBQ women face because of the men who want to “fix” us. We don’t always talk about the men who take our queerness personally and the “corrective rapes” that sometimes follow these public assaults on our sexuality. In my own experience, I’ve noticed that many of the monsters that lurk on our streets specifically target women who do not conform to hegemonic standards of femininity. Furthermore, the attacks increase disproportionately when race is factored into the equation. 41% of Black and Latina women versus 24% of white women experience street harassment regularly, as noted in the SSH report. For queer Black and Latina women, racism and homophobia can triple the axes of violence.

Trans women by far face increased persecution in public spaces, and are harassed by both men and women both because of their womanhood and their trans status. Given the murders of Islan Nettles, Ashley Sinclair, Kelly Young, Cece Dove, Amari Hill and countless others murdered as recently as 2013, it’s important to remember that the harassment of trans women and especially trans women of color isn’t just a microaggression; it can easily become deadly. Certainly, cis and straight women suffer from street harassment, but the degrees of violence and victimization multiply with every added marginalized identity.

In LGBTQ spaces, we do talk about the verbal and physical attacks queer people face and the disproportionate number of trans murders. However, I want these issues to feature at the center of mainstream conversations about street harassment. We need to put street harassment into perspective, especially for LGBTQ women. Street harassment is not a concerned suggestion for us to dress more modestly, nor is it a mere inconvenience. When street harassment functions as a way to enforce compulsory heterosexuality, it’s violence and it can be murder. Harassment is an epidemic for all women, but for those of us additionally marginalized because of sexual orientation, race, gender, and/or gender presentation, we have even more to fear. The streets are what connect us to our communities and community members. They should not be sites of oppression and until we honestly confront the dangers different individuals face on their streets, we cannot figure out how to make these spaces safe and end street harassment.