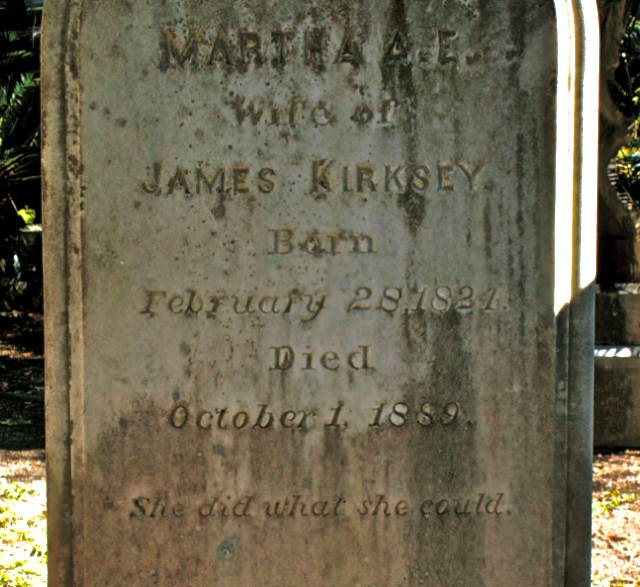

There’s a reason the Bonaventure Cemetery makes its way into every suggested to-do while in Savannah, Georgia. There is, of course, its immortalization in John Berendt’s Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil. There are the grounds, which amount to a maze of ornate architecture, wrought iron fencing, and centuries-old oak trees draped with hanging moss. There are the creepy statues like the “Bird Girl” from Berendt’s book cover, and “Little Gracie,” the memorial of a 19th century fancy-girl who died in childhood and now sits inside her own grief prison. There is the fact that it is known to be incredibly haunted. There is also something that hasn’t been advertised as a selling point, but should. It’s the headstone belonging to Martha A.E. Kirksey, born on February 28, 1824, whose tombstone reads:

Martha A. E.

Wife of James Kirksey

Born

February 28, 1824

Died

October 1, 1889

She did what she could.

She did what she could.

When I saw this grave I held two equally weighted feelings in my chest. The first was a oneness with the human race — a top to bottom wholeness. The second was fury. Just a bunch of rage that the perfect epitaph was etched over a hundred years ago. I also had questions. Who was responsible for this? Was it her own doing? Was it her successors? Did she have this planned for a long time or was this a fleeting thought after particularly bad day? Was it even a bad day by her standards? Was the person carving this into stone as moved as I was? Was there push back? Were the families of neighboring graves aghast?

Because even though this kind of candidness would transcend any cemetery, this was Bonaventure. It was the final destination for many of Savannah’s then “elites,” and high society in the 19th century South was built on things like status, formality, and presentation — not a drawing back of the curtain. And then there Martha goes, putting out a drunk-aunt-in-a-bathing-suit vibe.

It called to mind a certain brand of comedy on Twitter from women who’ve amassed tens to hundreds of thousands of followers despite their non-celebrity status, and who regularly tweet about things like eating whole rotisserie chickens at a playground full of children while drinking wine out of a carton. Martha embodying this modern energy in a world so far removed from ours with such efficiency had me spinning. So, what in Martha’s life lead to this? I had to find out. Indeed: who is she.

The story of Martha Kirksey is a little like accidentally falling asleep in the afternoon and waking up five hours later. You’re disheveled and confused, you’re sweating, you’ve missed everything you were supposed to go to, it’s too late to get food, and you just have to sit there knowing you’re not going back to sleep any time soon. It’s not the worst thing to ever happen, but it’s not ideal.

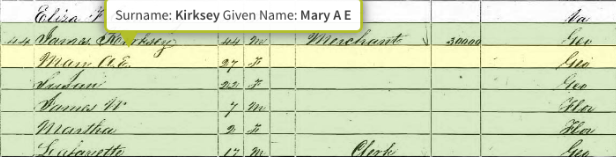

Records associated with Martha A.E. Kirksey on Ancestry.com mention a Martha Germany, daughter of W. Germany, in an 1840 US Census. In 1840 she was listed as 17 years old, even though this math makes no sense if she was born in 1824. This was a theme I found that followed Martha for the rest of her life — the men in it wildly oscillating from a year, to two, to as many as four years off Martha’s actual birth date on their census reports, because who has the time, really, to know how old your daughter or wife is.

A year after appearing on a census report for the first time, Martha at 16 or 17 years old married James Kirksey — a man 17 or 18 years her senior — on June 16, 1841, becoming his second wife. Ah, that classic love story involving a 16-17 year old meeting her 33-34 year old prince.

James Kirksey made his living as a merchant and I definitely know what that is! What I also know from estate records is he made a ton of money doing it. It’s how he and Martha — plus both of James’s daughters from his previous marriage, Susan, then 11, and Lafeyette, then 8 — were able to afford to live on the 4th largest estate in the nation. Thrown into marriage as a teen and now responsible for two stepchildren who are themselves budding teens seems like as good a start to one’s life as any!

Nine years after James and Martha’s marriage, an 1850 census includes two new names: James W., 7, and Martha, 2. You would think, given the names and ages, they’re Martha’s children. Oh, but you’d be wrong. The children’s mother is listed as Mary Ivy, James’s first wife. And on that same 1850 census Martha is now listed as…

Mary.

“It’s really just easier for me to call you Mary since I’m used to it.” Your husband having children with his ex-wife when you’re newly married is bad, but having your name be taken by one of those children that aren’t yours and then going by said ex-wife’s name as a placeholder is much, much worse.

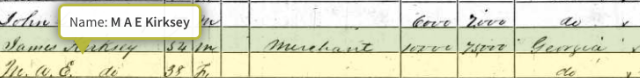

By 1860 Martha is just listed as M.A.E Kirksey.

Why bother, right? Three letters are fine. It’s not a big deal. I’ll just be back here laying on some balled up clothes as a bed.

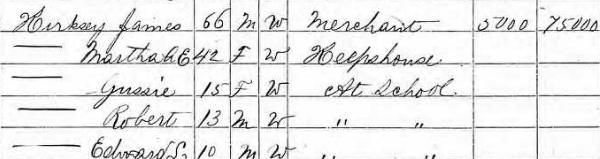

Fast forward ten years to 1870 and Martha and James are approaching their 30th year of marriage. Thirty years! Hard not to know every single detail about another person ten times over by that point. Except this was the census that James managed to miss Martha’s actual age by a full four years. On the upside, according to that same census there are three new children in the Kirksey household, and Mary Ivy’s death in 1850 means that Martha is probably the mother! Plus, Martha gets her given name back on record and she’s listed as having an occupation for the first time! “Finally, some real recognition from the man that knows me best. I wonder in what descriptive way my husband will at last acknowledge my presence on earth.”

Keeps house.

Despite this, 30 years was probably monumental for Martha. She’d stood by her husband for decades, she grew with him, and whether or not their marriage was born out of true love, she probably needed him in more ways than she knew. In 1878 her youngest would turn 18, and with that last child on their own probably came a chance for their marriage to cycle into rebirth. Except her husband died that same year.

Then — in what I can only assume was an homage to her late husband — Martha listed herself as Mary E. Kirksey on an 1880 census. “He did love to call me Mary.” Nine years later, widowed now for eleven long years, Martha Kirksey died.

According to four Chatham County Will and Probate records, Martha left sums of $10,000, $22,500, and $500 (ouch) dollars to her children and their families. I can’t find the remaining 30,000 odd grand that was listed in the assets of her estate. Hopefully in the last years of her life, she spent it entirely on the 19th century equivalent of carton wine.

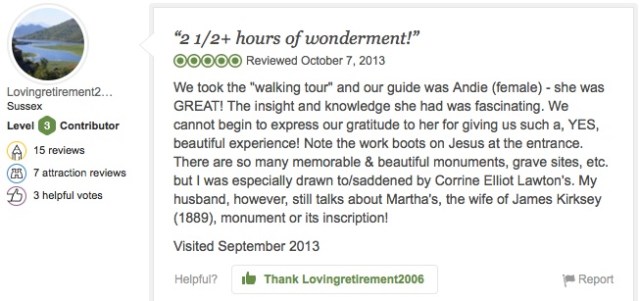

Even in death, Martha kind of gets the short end of the stick. Her only shout out before this is from a post on TripAdvisor from user Lovingretirement2006 entitled “2 1/2+ hours of wonderment!”

“Monument or inscription.” May Martha rest in peace, because she really did what she could.