feature image via shutterstock

Last week I was in a bar with a few friends, all graduate students who funded their studies by teaching undergraduates, just like I’d been until recently. One friend — a very sweet and gentle man, of large, imposing stature — had been having trouble with a belligerent and disruptive student, and was asking us for advice about how to handle it in class. Someone — another man — advised laying down the law, illustrating to the rest of the class that this wasn’t acceptable. “Ask him in front of everybody why he thinks this is acceptable behavior in your class. Call him out where other people can hear you.” These were generally good ideas, I agreed. “But it’s important to do what’s natural to your teaching style,” I said. “If you’re not as authoritarian, if that’s not authentic to you, you don’t have to fake it. Maybe see if you can make a joke out of it when they misbehave, so other students are laughing with you instead of with them. Or if they’re trying to get a rise out of you, you can act really indifferent, apathetic.” I wouldn’t have considered any of the strategies my friend recommended very feasible for me back when I was still teaching; I didn’t have a lot of faith that my “laying down the law” as a 25-year-old woman would have carried much weight; it may even have backfired. In fact, during the whole discussion, I had a hard time really focusing on being helpful. Don’t ask me, I wanted to say. You’re a tall, burly man with a deep voice and degrees more prestigious than mine. You’re like Dorothy in teaching Oz — you can go home anytime you want, all you need to do is click those particular ruby slippers three times.

It’s not groundbreaking to note that the strategies required to succeed in teaching, a highly interpersonal job, are different for people of different genders. In the same way that we’re conditioned to read the same behavior by a politician, a rapper, or a bartender differently depending upon their gender, the social maneuvers a teacher need to make are calibrated differently by gender. This recent interactive chart of teacher ratings taken from Rate My Professor feedback is a fascinating, if limited, way to explore the ways that gendered expectations play out in the classroom. It really works best as a tool for exploration, as not much definitive can be extrapolated from the frequency of words alone. It tells us not so much how certain values are applied to different instructors, but whether they were considered at all. Even so, some obvious trends are telling: the mention of the word “nice” is skewed female, suggesting that we don’t tend to value niceness as highly when considering a man’s efficacy as an educator.

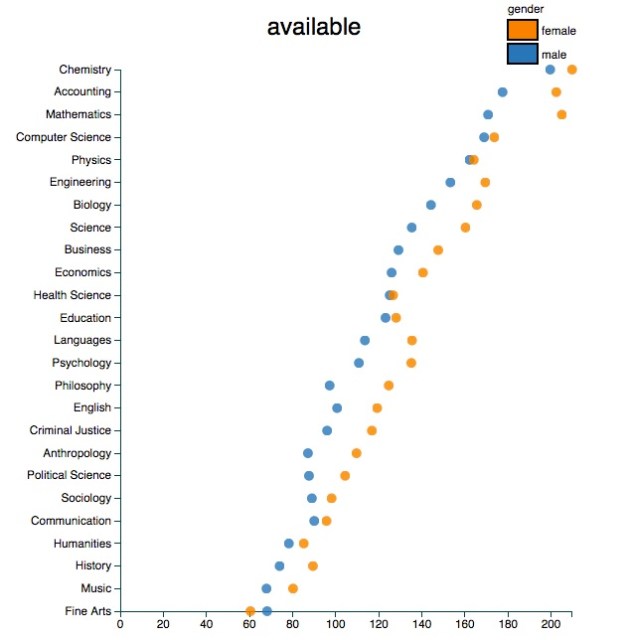

As a former instructor who was frequently frustrated by the many students who expected me to answer emails sent at 11 pm within the hour or were annoyed not to find me in my office at 9 am on days when I didn’t have office hours, I was interested to see a similar trend for the word “available” for most fields — perhaps echoing the cultural trend of women’s time not being considered as valuable as men’s, and the expectation that women be available to help or support others at all times. I wonder (without any definitive way to check) if my male colleagues were asked for meetings after 5 pm or on weekends by their students as often as I was. Although I didn’t have children or a family to care for, many women do, making this an especially outlandish demand that many students still feel entitled to make.

While Rate My Professor is an easily accessible source of information for sociological projects like this, it’s not a particularly important one in the real world, at least not compared to official course evaluations internal to a college or university. Whereas Rate My Professor is usually for students by students — figuring out that you should take Intro to Econ with Kant instead of Lacan, because Kant has a chili pepper and Lacan assigns too much homework — internal course evaluations are used in part to decide whether instructors should be granted more (funded) teaching positions in the future, and as assessment criteria if the instructor later looks for a teaching job at another institution (which many, if not most, in academia aim to do). Although that data is much less accessible to the public for analysis, it’s reasonable to expect that many of the same unrealistic assessments of female instructors are reproduced there, with more urgent real-world effects for the instructor.

Which is why this is a particularly frustrating example of the ways in which base sexism functions — because perceptions of women instructors’ personalities, as filtered through the gendered double standard both of educational institutions and individual college students, in their imperfect sleepy hungover youth, have very real consequences on the careers of female instructors and academics. What’s more, they have very real consequences on the educational experiences of students; when I’m worrying about how to teach without coming off as a bitch because I expect students to be quiet when I’m talking, I’m not thinking as much as I should be about whether my students are really learning.

My personal cross to bear as a female instructor — as someone who, in addition to being a woman, looked young enough that older professors sometimes mistook me for an undergraduate in the department office — was concern about being taken seriously. I agonized over my outfits, hair, and makeup; what formula of formal/feminine/hip/mature would communicate that I was professional and grown up, and so should be listened to? (It wasn’t uncommon for my male colleagues to teach in jeans and hoodies.) When a student disagreed with either the text or my own lecture, I often felt like I had to prioritize maintaining my own credibility when I would sometimes rather have had an honest (and educational) discussion about how yeah, these things are complicated and the academic answer isn’t always the right one. Other instructors in my grad program would sometimes use examples from their own personal lives to illustrate ideas in the classroom, but I never felt very comfortable doing so — I was too aware of the fact that many people think of women as being professionals OR having a personal life, and worried that if I acknowledged the latter, I wouldn’t be seen as the former. I rarely weighed in on how the issues we discussed in class — the sexism implied by Jamaica Kincaid’s Girl, the flawed rhetoric of advertising — had ever affected my own life, even when it could have been helpful, because I was worried that if I was perceived as having a personal bias about any issue, it would be a reason for my students to stop taking seriously anything I had to say about anything. It’s anecdotal, but I’ve never heard any of my male colleagues in academia worry about any of these things. I suspect this pattern holds true for other women, for many other women.

For these reasons and others, I also (almost) never came out during my time teaching. (I’m not alone; a recent poll revealed that only a third of LGBT teachers in the UK said they could be “out and safe” in schools. The issues they struggle with hold true globally, as this piece from the Atlantic illustrates.) I had at least one queer student virtually every semester I taught, whose identity I knew about either because they were out in class or because they mentioned it in writing assignments turned in to me. I assume there were more that I never knew about. I thought about them a lot, and what responsibility I might have to them, and how big a deal it had been to me when a beloved teacher told me she too was bisexual in the 11th grade. (Hey, Ms. M!) I did come out to one student, my very last semester as an instructor; she had brought up her own queerness in a one-on-one meeting, and sensing a need on her part to feel less alone, I had haltingly told her. I thought I would feel relieved and closer to her; instead, I just felt more anxious. What if she brought it up somehow in class?

Part of my reasoning for never coming out in most capacities was that in the state where I was teaching, it was still legal to fire someone because of their sexual orientation. While I knew several out teachers and my department never held a bigoted agenda, academic institutions will stoop pretty low if they decide they want to get rid of someone for political or economic reasons; it’s best not to give anyone anything to work with. (I did know one person who had a student object strenuously to the teaching of Brokeback Mountain, and experienced some pressure from the administration because of it.) But mostly it was because I was so anxious that if my students knew I was queer, it would be used as a reason why they didn’t need to take any of my urgent pleas to think critically and question the rhetoric of their communities to heart. That while my straight white male colleagues’ curriculum would be accepted as objective fact, mine would be written off by my students as a subjective screed, because the farther they saw my identity shift from that ‘neutral’ starting point, the less they would need to respect me as an educator and as a person, and the harder I would have to work to even get them to listen to me about commas. It’s likely part of why LGBT teachers are less likely to challenge homophobia in their classrooms — we know that we’re always risking making ourselves and our identities the focus of attention, and not the lesson, even at the risk of other students feeling less safe.

It’s important to note that there are increasing obstacles in the way of actually teaching the farther you get from the straight white male ideal, including many obstacles I never had to face — a friend who’s a queer woman of color has had students ask if she’s really qualified to teach English as a language, because being visibly brown is assumed to signify foreignness, is assumed to preclude expertise. It’s hard to imagine the student who asked that question really taking my friend’s lessons on anything to heart.

Trying to navigate sexism, heterosexism, racism and so much more in the classroom can often feel like it eclipses the job itself; perhaps even more insidious are the ways in which these concerns undermine the job at its foundation. While I was teaching Thought and Writing, I taught my students that if their understanding of logic and rhetoric was thorough enough, then their arguments and ideas would be taken seriously. At the same time, I was consciously editing and contorting myself because I felt that as a young female instructor, my own arguments and ideas would be dismissed, despite being the most educated person and (I hope?) the best writer and rhetorician in the room. During the personal essay unit, I taught them that relaying their personal experiences with vulnerability and honesty, describing them with as much concrete detail as possible, would ensure a connection with the reader that would make the scariness of personal revelation worthwhile. In those same in-class discussions and one-on-one meetings, I was taking care to conceal as much of my personal life and identity as possible, because I believed it would make it less likely that the same students would build a connection with what I was trying to teach them. Would my lessons on these topics have been more grounded in reality, and therefore more useful, if I had been able to acknowledge these contradictions in the classroom?

I don’t know for sure, but I do know that the position I was in as a female instructor didn’t help anyone, me or students. While teaching is often considered (and in many ways is) a “caring profession,” frequently associated with women, not many “feminine” traits really lend themselves to the field. It’s helpful to be understanding and compassionate, to have patience, be supportive and listen, but it’s also important to set boundaries, to challenge people in ways that often make them uncomfortable, to be direct and to welcome — even encourage — conflict to the extent that it can be productive to learn from. It’s not a coincidence that men as a group are often more successful than women in the “caring” professions. While women generally (correctly) understand that they need to default to gendered expectations in order to get anywhere at all in their profession — choose being a ‘team player’ over being assertive, prioritize the feelings of others over their own ideas — men feel (and are) free to be confident, ambitious, and confrontational. Women know that they’ll likely face pushback for doing these things, in any field; this may make them reluctant to do so when teaching, which is both totally rational and bad for students.

I got my MFA and left my program in May of 2014, leaving teaching behind with it. For now, at least, I’m glad to be done with it. I now work full-time with other queer women on this very website, providing feedback on their work in a way that’s not dissimilar from how I used to give feedback to students (although, granted, it’s now in a less bureaucratic and high-pressure environment). The difference is stark: when I’m not tasked with figuring out how to translate my thoughts out of my own lived experience and into the most “neutral” one I can imagine, I can focus on what the person I’m working with actually needs to hear. The difference in how much better am I at doing that job when I feel like I can be authentically myself, without so strenuously directing my own performance in the role of teacher, is remarkable. What would happen if teachers who weren’t straight white men were consistently able to feel that way in classrooms? Course evaluations aside, there’s no telling how much all of us might be able to learn.