Young girls who grew up in the ’90s had a slew of women to model their lives after. A Spice Girl for every personality you could strive to mold, teenage witches, vampire slayers, Britney, Christina and their many imitators. For me, that woman role model shot fireworks out of a C-2000 bazooka and lit up an entire arena. That woman had muscles on muscles and backed down to no man. That woman was WWE superstar, Chyna.

My chest would tighten every time her theme song boomed through my television speakers. An anthem that ordered, “don’t treat me like a woman, don’t treat me like a man, don’t treat me like you know me, treat me for just who I am.” Without even watching her fight, the viewer is issued a challenge: to examine what we attribute to being either a woman or man, and to disregard all of it. Once the tune ended, the bell rang, this entity lifted her opponents over her head, landed blows that sent them flying, lounging on them for an effortless three-count pin. Whatever Chyna was, I wanted to be it. I was hooked.

Being a ten-year-old fan of the 9th Wonder of the World (as she was often dubbed in wrestling culture) was delicate. The audience to whom you boldly confessed wanting to look like her could encourage or stunt you in this impressionable stage. While some would tell me I could “be whatever I wanted to be,” more often my desires were countered. “She looks like a man,” they’d insist. “You don’t want to look like that.” Had I not seen her opponents ridicule her for this very reason and witnessed them powerbombed for their ignorance, perhaps it would have stuck.

Wrestling fans were adamant about questioning her womanhood. Rumors that she was trans could not be thwarted, and while of course it isn’t embarrassing to be trans, nor would it have made Chyna less of a woman to be trans, the rumors were intended to embarrass and to call her womanhood into question. Signs about her then-lover that read, “Triple H is part queer” popped up in the audience. Wrestling was a lot more “adult” then, and the public’s tongue was even less progressive than it is now. While the “divas” (women wrestlers), who earned centerfolds in magazines and the privilege to be valets to their male co-stars, had matches in which the objective was to strip your opponent down to her bra and panties, Chyna was tossing men over the top rope, disqualifying them in the Royal Rumble. While girls in my high school gym would lazily walk on treadmills until the bell rang, I quietly did bicep curls in the corner of the weight room. Chyna planted a seed in my head that I couldn’t shake.

But Chyna’s accomplishments in wrestling have been enumerated countless times by those who know her legacy isn’t being recognized. Words like “trailblazer,” “pioneer,” “legend,” are exhausted. She remains, 17 years later, the only woman to hold the intercontinental championship, and has done so twice. She was the first woman to enter the Royal Rumble (that wouldn’t happen again for ten years), the only to participate in the King of the Ring tournament, was once the number one contender for the World Heavyweight Title, and parted with the company the only undefeated Women’s Champion.

So while her physical prowess is undeniable, Chyna was also a warrior in less conventional ways. Ways that the media likes to wield against her, painting her as a trainwreck. Ways in which, analyzed under the wrong lens, could reduce her to another campy, real life John Waters character; a spectacle and not a person.

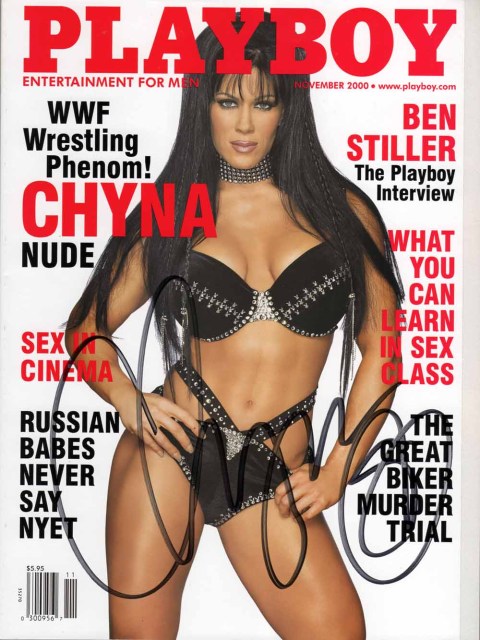

In 1999, Chyna’s then off-screen lover, Triple H, had an affair with the WWE chairman’s daughter and the company’s chief brand officer, Stephanie McMahon. Faced with the difficult decision to continue to work for McMahon and bring in the large revenue she was generating at the time, Laurer stayed the course. When the affair came to light, the public found Triple H without fault, as if mustering up sexual attraction to such a brawny woman was the act of a good samaritan; that she was lucky to have ever bagged a man at all. She proved them wrong when she made the decision to grace the cover of Playboy in 2000 (much less her porn career, which she spoke of positively in one of her last interviews). It remains one of the magazine’s best-selling issues, and she earned herself a second cover in 2002. This decision stands out as an autonomous one, given its timing at the height of her wrestling career, and a bold one. Many women who were said to be as “good as the men” may have shied away from controversial sexual endeavors, worrying they would lower her credibility in the public eye; Chyna did what she wanted to do, as she always had.

WWE was happy to spin a wildly entertaining story line from her Playboy issues in which both her on-screen lover, the late Eddie Guerrero, and a trio called Right to Censor wanted to keep the issue from hitting the shelves. But when the new authority, made up of Triple H and Stephanie McMahon, grew increasingly uncomfortable with having “the ex” around, they gave her the pink slip and her Women’s Champion belt was awkwardly vacated. Despite her numerous accomplishments within the company, the WWE has yet to induct Chyna into the Hall of Fame. In an interview with Stone Cold Steve Austin, Triple H explains: “I got an eight year old kid. My kid sees the HOF and my kid goes on the internet to look up, ‘oh, Chyna, I’ve never heard of her.’ He punches in her name and what comes up?”

Chyna’s unwavering persistence after her severance from the company began with her name. Unable to continue to go by the name she worked so hard to build up, she legally changed her name from Joanie Laurer to Chyna. Watching your unfaithful ex-partner rise to authority by association with “the other woman” is humiliating. For many, it’d be enough to turn them away from the environment that spawned the situation, but Chyna knew that she deserved to be lionized by the company she did so much for. Her attempts to bury the hatchet are archived on YouTube; the hashtag “#ChynaHOF” is heavy with pleas from both her and her fans to the company. WWE stars, including Mick Foley and Jake the Snake, got on board to rally for the cause. When Chyna’s manager, Anthony Anzaldo, attempted to contact the WWE regarding unclaimed royalties, the operator discloses that she was instructed by Vince McMahon “not to take any calls related to her.” Until the day she died, she continued to fight tooth and nail for her rightful induction.

The treatment of her death, too, is tragic. Not only was her memory forgotten within hours, especially after news broke that music royalty, Prince, had also passed away, but those who did report her death often focused only on her “final days,” in which she wrestles with her demons on vlogs she made. Chyna was not selective with what parts of herself she put on display. She knew she was polarizing, she allowed anyone willing to contribute $195 to her documentary’s funding to say whatever they felt about her, good or bad, and she would include it in the film. Her raw vulnerability was uncomfortable for most to witness, and many used it to paint her as a person the WWE had no choice but to avoid. I, personally, see it as another part of what made her so badass. Chyna was never about being an easy person to respect. Everything she did, whether it was pinning a man to the mat or having sex on camera, made people uncomfortable. She was about agency, and that’s what the public fails to report about her.

And as for that ten-year-old girl, glued to the television set, whose parents laughed while I leaned in closer, waiting for the referee to slam his hand on the canvas the third time? She’s competing in national powerlifting competitions and teaching self defense. I have Chyna to thank for that.

Comments

Thank you for this!

I loved the WWf and more I was

Young.. But REMEMBER ALL

I don’t have any personal attachment/memories like this, but this was a touching tribute. I’m glad you wrote it.

As an ex-wresting fan(during her era) thank you for this. I don’t think I ever met her, but I did get to meet a few wresters over a decade ago after a show, and boy some of them are shorter in person that on TV. Stephanie being one of them(didn’t meet her, she was just in the back hanging with HHH).

Thank you for this.

Chyna was a little late for me.

I had Xena and Buffy, but also Cynthia Rockroth (whom I have never forgiven for getting a breast enlargement and becoming a sell out),Michelle Yeoh and one other Lady who’s name I never caught. (Taping things on VHS in a timely manner is an art not easily mastered).

I needed those women to give me agency over my own strength.

I needed them every time someone asked me whether I wanted to look like a man.

I needed them to know that it was possible to own up to my own power.

And I did.

I still do.

Fantastic tribute, thanks for this.

I liked this, and heck yeah to powerlifting and working class femme poetry.

Thank you for writing this.

I absolutely adored her on Third Rock from the Sun. I loved her relationship with Harry. I developed more and more admiration for her (and a crush) the older and queerer I got. I’ll miss her.

This was beautiful thank you so much for this.

I had no idea who Chyna was until the headlines about her dying showed up in my FB feed, but I read this whole thing because it was so thoughtful. Thank you.

As I said in another post, I have so many feelings about Chyna. I was 5/6 when my mother and I watched wrestling every Friday. Aside from all of the fun loving memories I have of that time, a prominent source of my enjoyment was watching Chyna sling grown men across the ring. Women, up until she came on the scene were treated as glorified trinkets. Every time they were in the ring it was to either hold the rope for their man or basically reenact softcore porn. I’m not trying to knock anyone for their personal choices but 5/6 year old me was not here for it. There was not a single care in my tiny body for women loving up on men and being treated like things. I already knew that there was something “different” about me. I wasn’t sure what but I knew there was something. When I discovered Chyna and Xena I started figuring out what that was. There isn’t anything wrong with being (for lack of a better word) “girly” but that, for the most part, wasn’t me and it still isn’t. I was so tired of not seeing me anywhere. I wouldn’t call myself a tomboy or any variation of the word (not that its a bad thing) but I wanted more contrast in the way the I saw women in the media. I wanted to be Xena and Gabrielle. I wanted to ride dirtbikes and be like Martha Stewart. I wanted to be Phoebe (from charmed) and be allowed to be as rough as the boys. So much of the media treated women as the “girliest girl to ever girl in the girl world” or the “tomboy that’s not like other girls” but rest assured, they made sure everyone knew that they both still LOVED men. So Chyna came into my life at an important time. She was unapologeticly herself. She looked the way she wanted, wore what she wanted, had a boyfriend but didn’t mind slapping men around in the ring. That is what I wanted to see. I would be plastered to the screen waiting for any glimpse or mention of her.I wanted to just exist in a way that made me the happiest. In a way that had no expectations or gender roles and just let me be. That is what I saw in Chyna. It was so cathartic to see who I was on the inside, on television. 5 year old me didn’t have the words to verbalize this but I just remember it feeling right.

I never fed too much in to having role models but she is the closest things I had to one. Not to mention that everyone I knew who met her sang praises of her being pleasant to be around and just really kind.

I didn’t mean to write this much and I’m tearing up now that I’ve put everything I’ve felt over the years into words. Its bullshit that she’s not in the HoF based on her merit as a wrestler alone.

Rest in Power

This article is such a moving tribute, I liked it very much.

I didn’t even know she passed away, OMG! I grew up watching her and WWF (perks of having a brother and being the younger one with no privilege to the remote control) and I absolutely loved her! Thanks for this beautiful piece.

I never really liked other female role models growing up because I didn’t fit their model. My role models were tough, bad ass and never backed down. That was Chyna, Xena, Buffy and Pink. Women like Chyna brought out this confidence that I lacked and made me realize I can do what ever I set my mind to. Other than my own mother, I lacked examples of strong women but this was remedied every time she was on screen. I really love this tribute because it was exactly how I felt and more. I thought a bit before writing. I wanted to know how much of an influence she had on me and to see if I still carried that same inspiration I had as a small girl. At first I would have said no but I find myself ready to take on the world everyday, unafraid to cry even in a fight, stand up for others, do what makes me happy and just be happy with who I am even if I don’t fit the criteria of a sexy woman. I still have the inner Chyna ready to body slam what the world throws at me.

Thank you so much for writing this.

Not a crier, but I cried.

I only knew of Chyna after her prime, my mother set the bar for the TV when I was a kid and the WWE was ranked with the Simpsons in programming she detested would demand “Change it or I turn it off”

I think I cried because I knew her as this sweethearted kind person who was so very wronged by the WWE and our society. And that she died alone the way she did.

But I know I cried because this tribute trigged this memory of laying myself bare, taking pictures of myself feeling so attractive because I had begun to work out again and felt this sureness and confidence in my body. To only feel like vomit when I heard the horror and disgust of the person I sent the pictures and took the pictures before.

The hard plains of muscle were an act of destruction to my “beauty” and I had defiled myself in their eyes.

I usually look back at that incident as the final warning bell that gave what I need to cut myself free of that toxic relationship because it was MY BODY and what I did with it made me happy, made ME feel good. I’m proud of the realisation it gave me

But fuck did the disgusted reaction hurt so much. I was a barely 18 year old baby baring it all for someone who claimed loved me and they threw it back like that.

Loving such a sweet person as Chyna couldn’t possibly be the act of a good samaritan.

Loving someone who’s not all soft curves isn’t an act of charity.

Loving someone whose hardest plane is the bottom of their foot isn’t an act of charity either.

Fuck that noise love is an ability

True charity comes from love and compassion, not pity.

Thank you SO much for writing this. I felt so upset that Chyna’s passing was overlooked by the WWE. This article is beautifully written, Leah.

Chyna was so much more than a wrestler. She was a force, she was a pioneer and she leaves a legacy behind which I hope no wrestling fan will ever forget. When I started watching WWF, I only remembered the glamourous ladies accompanying the men to the ring. Their roles were limited to simply being accessories.

I was 10 when Chyna made her debut. She was strong and stoic and fearless. I wanted to be just like her! There were men who feared her, men she had wrestled with and won. When she entered the Royal Rumble and eliminated wrestlers, I felt proud – as though I had accomplished something. And I will never forget her match against Jeff Jarrett and winning the Intercontinental title. Sure, people say it’s all scripted and whatnot. But her pain and struggles were real. She wanted to prove herself. Chyna winning a match was equivalent to women everywhere achieving goals that could have been impossible to reach. I celebrated her wins and consoled her though the television when she lost.

I looked up to her and when I read her autobiography, I loved her honesty and I cried over the pages where she wrote about her tough times. I was just a teen, running around in a skirt and playing soccer with the boys during recess. Chyna made me feel like I could be just as good or even better than the boys. Just like you, Leah, I loved it when her theme song came on and she walked out like a BOSS. She was just so special.

I’m sorry for the lengthy rambling but I just couldn’t share all of these with anyone else. No one understood how much of an impact Chyna had on me. I’m so thankful that you wrote this article.