When people discuss the feminist movement, they leave a 40-year gap in its history between 1920 and 1960. The first wave is thought to have “ended” in 1920 when the 19th Amendment was finally passed, codifying a woman’s right to vote in the Constitution. Meanwhile, the second wave is defined as beginning in the 1960’s, when nobody burned bras but a bunch of people started rumors that feminists were burning bras and thus, the world changed.

But that’s not exactly right.

The nearly half a century that passed between the first and second waves of feminism was a period of great transition for what hadn’t even yet been named the “feminist movement.” But whereas the second and third waves, for the most part, melted into each other – with a “women’s liberation movement” in the ’60s paving the way for today’s social justice universe – the first and second were divided by revolutionary changes in American society.

First wave feminists weren’t like us. Sure, some were queer. Some were badass as fuck, if we’re gonna be real. But many of them had beliefs and value systems that clash with our modern conception of what gender equality really looks like. Susan B. Anthony was staunchly anti-choice, as were many of her counterparts. Many were what we would probably consider religious zealots. Some implicitly or explicitly advanced and endorsed racist policies and social ideas. Others still perpetuated problematic ideas about class and capital.

First wave feminists weren’t like us. And they damn well weren’t like their second-wave counterparts, either. By the time the women’s liberation movement really kicked into gear in the ’60s, women were fighting for sexual empowerment and free love, abortion on demand, equal pay and access to career and educational opportunities, and an end to what we now call rape culture and domestic violence.

And the 40 years in-between are what made all the difference.

Between 1920 and 1960, the feminist movement changed. Fights about women’s labor shifted from protective laws to non-discrimination clauses. New leaders came, old leaders fell out, and some first-wave icons pushed to advance their agenda from voting rights to full legal equality in all areas of life. Women, who lacked a language or legal refuse from abuse and sexual violence when the first wave began, started to talk, instead, about sexual freedom and autonomy.

Some of these changes were internal. In some cases, the women’s movement simply progressed, with the more revolutionary first-wavers recognizing that their victory in the suffrage movement hadn’t ended all the social ills that shaped women’s lives. Some were external: America changed, other social justice movements mounted, and attitudes and ideas impacted how women proceeded in the fight for equal rights.

The following feminist milestones changed the movement forever, and in the process paved the way for a more radical, inclusive, and far-reaching women’s movement. (I’ve listed them, as accurately as possible, in chronological order.)

Alice Paul Fought For The Equal Rights Amendment

Alice Paul was a suffrage crusader, to say the least. She brought militaristic strategies from the UK back to America as a young and spritely advocate for the woman’s vote, and all of us largely owe our enfranchisement to her refusal to back down and her persistence in demanding it. But Alice Paul didn’t rest once the 19th Amendment was ratified; instead, she pushed on and asked for even more.

When suffrage was won, Paul was the head of the National Woman’s Party, an organization which changed gears and began lobbying for full equality after women won the vote. Paul, recognizing that the right to vote alone would not make women equal to men, drafted and presented the “Lucretia Mott Amendment” at the 75th anniversary celebration of the Seneca Falls Convention.

That was in 1923. Her amendment, which is now known widely as the Equal Rights Amendment, was short but oh, so fucking sweet: Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.

The ERA wasn’t exactly a natural next step for the first wave of the women’s movement. Paul’s notion that women should be completely equal to men – and, thus, surrender all of the totally patronizing “protections” they were given and guaranteed at this point via legislation and custom – split the movement, and divided the nation decades later during the second wave. Nonetheless, Paul pushed on in her challenge for constitutionally guaranteed equality, fighting state-by-state as well as in Congress to ratify the amendment and, later, pass local versions of it where she could.

The ERA was introduced in every Congress between 1923 and 1970, but either never left committee or failed to pass. (Finally, in 1973, it made its way through Congress – only to fall short of ratification in 1979 by a three-state approval margin.) But ultimately, the impact of the ERA became obvious as the second wave began to articulate its demands, many of them political and policy-based.

Paul’s audacity to dream of a world in which women were ensured their equality and supported in their liberation with legal power allowed feminists for decades to come to wage political battles and win. Her work literally translated the victory of the suffrage movement into an ongoing fight for political equality.

The Roaring Twenties Gave Way to the Rise of the Flapper

If there was ever a predecessor to the hippie girls who championed free love, it was the flapper.

The term refers to the women of the period who engaged in offensive acts such as having short hair!, drinking!, dancing!, having sex!, and other various forms of entertainment and social engagement that, until the 1920’s, were inconceivable for women. It was the end of an era of victorian morality, and many women were ready to throw on some heels, turn up the jazz, and go out on the town.

Although flappers were bonafide party girls, they also advanced women’s rights by breaking social norms in other areas of life. They were often working women, and many of them voted and were vocal about social justice issues like feminism. And despite popular representations of this period, the fashion and social trends of the flapper reached across racial communities and, in some cases, united them as well.

What flappers symbolized for womanhood and, in turn, for the rest of American culture was the new sense of independence, freedom, and consumerism that had come to define post-WWI America. Prohibition ended in 1923, and hedonism was the next big thing. The automobile was widely available, giving Americans from across the nation a newfound sense of adventure. People were finally ready to throw caution to the wind, spend to their last dime, and embrace frivolity.

Flappers, in this way, are long-lasting icons of the entire period. But they also ushered in new attitudes and ideas about womanhood that would change the course of the feminist movement in the future.

Flapper culture also coincided, in some ways, with the Harlem Renaissance, which amplified the voices of women like Zora Neale Hurston and led to greater racial consciousness and community. These works and relationships went on to fuel movements for racial equality, which coincided with second-wave feminism in the 60’s. And despite the economic decline in the 30’s and WWII, ideals like sexual freedom and independence from men proved to be long-lasting in the movement for women’s liberation, as did women’s economic power. The 1920’s were also a decade in which media targeted at and catering to women was on the rise, which would ultimately lead to the feminist magazines and publishing houses of the second wave.

Suffragists often expressed displeasure with the notion of the “new woman” of the ’20s, opting instead to be conservative and boring. But the flapper never really disappeared, and remnants of what she meant live on in our notions of culture today.

Women Demanded Birth Control Access

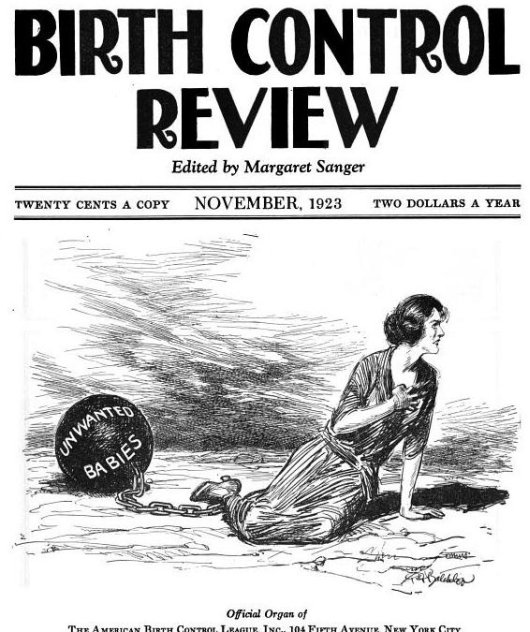

Although it technically began before 1920, the 20’s and 30’s were a time of mobilization and movement-building for birth control advocates. Women like Margaret Sanger, Ethel Byrne, Rosa Pastor Stokes, Emma Goldman, and Mary Dennet rose up in these decades to demand their right to distribute birth control information, provide women with access to contraception, and imbue medical professionals with the impetus to take family planning seriously and see it as a woman’s right.

All of these things were revolutionary, and all of them violated the Comstock Laws in place at the time that prohibited direct distribution or even distribution of materials discussing “obscene” material, contraception included.

By the time women won the right to vote, Sanger had launched The Woman Rebel, a monthly contraception newsletter, in order to stir fights around these regulations and, ultimately, see them change. She had also opened the first birth control clinic in America, in direct defiance of the laws. Her supporters had formed the National Birth Control League – the first organization of its kind.

For these actions, she and her compatriots suffered. They were imprisoned. Their clinics were raided. They were harassed, threatened, and attacked. But they refused to stop helping women – particularly those who were economically vulnerable – avoid pregnancy. And by the time the 1920’s and ’30s were in full swing, they weren’t fighting alone.

Public acceptance for birth control was on the rise by the time Sanger opened a second clinic in 1923, and the birth rate was on the decline. Dozens of clinics followed in its stead, though they still faced police raids and legal scrutiny for opening their doors. In 1930, a judge ruled that distributing condoms by mail should not be illegal; in 1936, a judge did the same when Sanger brought the legality of diaphragm distribution to the courts. In 1937, the American Medical Association categorized birth control as a “normal medical service,” opening the doors for medical professionals to be educated on contraceptive methods and for women to more easily be prescribed them.

By 1942, the two major birth control organizations in the country had come together to form what we now lovingly know as the Planned Parenthood Federation of America.

The birth control movement achieved most of its goals as the second wave was still gaining momentum: In 1960, the FDA recognized oral contraceptives; in 1963, ACOG endorsed the spread of family planning information.

One of the driving forces behind the birth control movement was the impact illegal abortion was having on women. Poor women and those who couldn’t access safer methods of obtaining the procedure were performing it on themselves, leading many to die needlessly in pursuit of smaller families and bodily autonomy.

The victories of the birth control movement made it possible for the fight for legal abortion to go on, which it did. Abortion and other reproductive health issues were key in the second wave, which ushered in Roe v. Wade and was a turning point in the larger movement for reproductive justice.

Author’s Note: If you have come here to tell me Margaret Sanger was a racist or a eugenicist, please read this first.

The Great Depression and World War II Sent Women to Work

Women’s foray into the workforce came in two parts over the course of the 1930’s and 1940’s. During the Great Depression, men’s employment declined dramatically while women’s increased with urgency, but often the jobs they filled were in what became “pink collar” sectors: administration and secretarial work, teaching and nursing, and working as seamstresses or doing work similar to their own domestic duties at home. Regardless, it was during this time that women forged a strong relationship with the labor movement, fighting for fair wages and treatment.

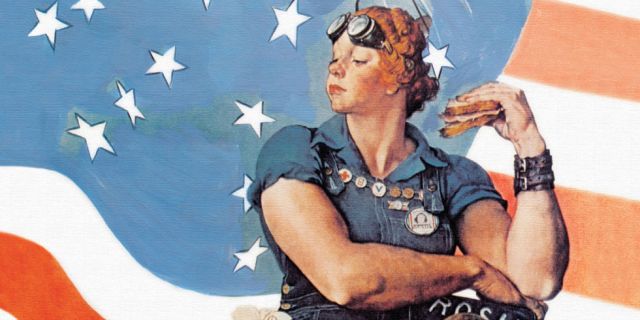

Then, WWII started. It was the beginning of a short-lived era of opportunity for the women back home in America as they filled the shoes of men fighting the Axis powers in Germany; they took on jobs that had them dabbling in manual labor and even engineering and construction in military plants and were even courted by said military industrial complex to do so as if it was their duty as Americans. However, when the men returned women were pushed out of the jobs they were now expert in and, often, deeply interested in as well, which was coincidentally the topic of a play I wrote for literally no reason as a child.

Despite the ways in which women had proven themselves through the Great Depression and WWII to be not only worthy of employment but capable of achieving the same mastery over their jobs as men, they faced social and legal challenges to accessing work opportunities. In some states, protective legislation limited the kind of work women could do and the hours in which they could do it; across the nation, they were painted to be “stealing” jobs from men, whose egos suffered greatly as they were laid off and lost their roles as breadwinners. Pink-collar jobs emerged during the 30’s in order to maintain a steady flow of work in certain industries for men, as well as out of necessity for women to be earning some wages while their men struggled to stay afloat.

Traditional views about the structure of families and rigid gender expectations for women as homemakers and child-rearers also made a comeback in the 30’s, undoing some of the social progress that would have enabled women to demand the right to work. When nobody is working and everyone is poor, it turns out, they begin to lack empathy and understanding for those who wish to add to the pool of applicants competing with them for a day’s wages.

The fight for women’s equality in the workplace, however, only grew stronger as the second wave neared. In the early 20th century, teachers fought for equal and fair pay, noticing that their industry expected them to be wives and thus thought it was okay to pay them less. The Shirtwaist Factory Fire and its ensuing labor rights battle also put women workers front-and-center as the labor movement began to develop and evolve. Although women would be refused entry into unions and dismissed by the male-led labor movement for some time, they didn’t surrender to unfair treatment. The battles to end workplace sexual harassment and wage discrimination, establish a living minimum wage, and improve labor conditions for workers in various fields had seeds in the 30’s and 40’s, despite its reputation for being a “void” in the feminist movement.

The Civil Rights Movement Shaped Women’s Lib

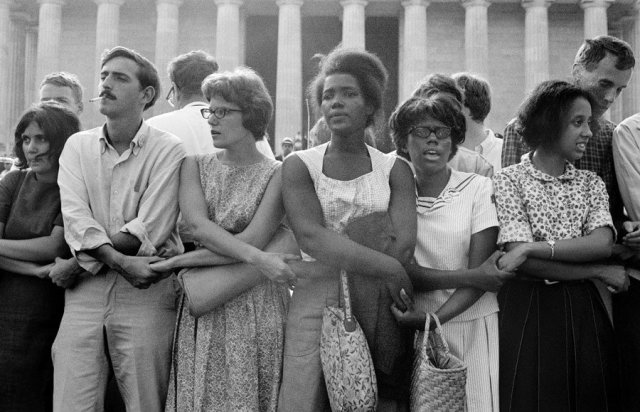

Many first-wave feminists got their start in the abolition movement, only to realize that they, too, were suffering from unique oppressions and discrimination based on their gender. Similarly, Black and white women alike who were active in the Civil Rights movement came away from the experience more aware and ready to act on the sexism that pervaded mid-century American culture. For some of them, this awareness stemmed directly from their experiences fighting for racial justice, in which women were acting as leaders and putting themselves on the line only to be cut out of decision-making and policy-based discussions and organizational leadership opportunities. (Remember that time Coretta Scott King was cut out of American history despite her decades of work around civil rights? She wasn’t alone.)

The women’s liberation movement also followed in the strategic footsteps of the civil rights movement, often emulating directly the kinds of actions and methodologies used to advance racial equality in order to similarly advance women’s rights. The second wave, like the civil rights movement, utilized large marches, acts of civil disobedience, consciousness-raising, and other movement-building tactics that enabled them to demand justice.

Despite the intersections between the civil rights movement and the women’s liberation movement, however, white women who ended up at the helm of feminism’s second wave often neglected the intersections between race, class, and gender which are now cornerstones of women’s rights activism. In this way, the civil rights movement also laid the foundation, in particular, for Black feminism and other multicultural and transnational feminisms, which strived to integrate conversations about race and gender and tackle social inequality from an intersectional perspective rather than a single-issue lens. Ironically, it was women of color and particularly Black women who laid the groundwork for much of modern feminism and, in particular, for the second wave, especially those who had been active and engaged leaders in the civil rights movement.

Ultimately, the Civil Rights movement served as an entry point for some women’s liberation leaders and an inspiration for others, as well as a working model for social justice movements that would remain viable into the next century. In the long-term, it also opened up dialogue about race within feminist spaces, as it did across the nation, which led to concepts like intersectionality which would lead the second wave into the third.

Recommended Readings for This Unit:

- “From Suffrage to Women’s Liberation: Feminism in Twentieth Century America,” by Jo Freeman

- “1930’s America – Feminist Void?,” by Mickey Moran

- “Participatory Democracy: The Bridge from Civil Rights to Women’s Liberation,” by Julia A. Clements

- The Timetable of Women’s History, by Karen Greenspan

Rebel Girls is a column about women’s studies, the feminist movement, and the historical intersections of both of them. It’s kind of like taking a class, but better – because you don’t have to wear pants. To contact your professor privately, email carmen at autostraddle dot com. Ask questions about the lesson in the comments!