Just Kids is the first book to ever make me cry. Not just shed a little tear, but to leave me sobbing and shaking on a crowded Sydney bus before I even reached the first chapter. The foreword was intense!

In said foreword, Patti Smith recounts the moment she discovered her former lover and collaborator Robert Mapplethorpe had passed away from AIDS-related complications.

“I was asleep when he died. I had called the hospital to say one more goodnight, but he had gone under, beneath layers of morphine. I held the receiver and listened to his labored breathing through the phone, knowing I would never hear him again. Later I quietly straightened my things, my notebook and fountain pen. The cobalt inkwell that had been his. My Persian cup, my purple heart, a tray of baby teeth. I slowly ascended the stairs, counting them, fourteen of them, one after the other. I drew a blanket over the baby in her crib, kissed my son as he slept, then lay down beside my husband and said my prayers. He is still alive, I remember whispering. Then I slept.”

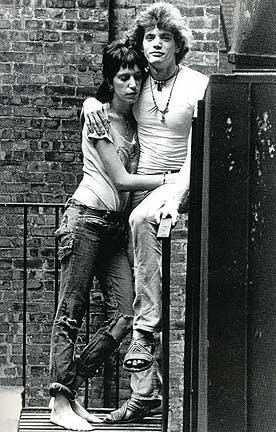

On March 8, 1989, the day before he passed, Robert asked Patti to tell the world their story. That’s what Just Kids is: an account of Patti’s and Robert’s life in New York during the late 60s and early 70s, a time when everyone worshipped Andy Warhol and listened to the Velvet Underground. It’s about the evolution of two young outsiders, both as artists and humans, who struggled between the need to eat and create and who strived to build the world they wanted to live in.

Just Kids made me feel similar to how I felt when I read Jack Kerouac’s On The Road for the first time. I was quickly sucked in to the romance of young artists trying to find themselves and their place in a world that labeled them eccentrics and outcasts.

There are moments when Just Kids reads like a roll call for 60s and 70s music, art and literary legends. It’s peppered with anecdotes featuring everyone from Jimi Hendrix to Janis Joplin to Salvadore Dali. At one point, Patti recounts how Allen Ginsberg bought her a sandwich because he’d mistaken her for a pretty boy. It’s a tale that would probably seem far-fetched if it weren’t described so vividly that you could have been there.

Just Kids opens with Patti’s teenage years, detailing how she fell pregnant out of wedlock and put the child up for adoption. Her mother encouraged her to become a waitress. However, having spent her teen years immersing herself in art and poetry volumes, Patti knew her calling:

“I longed to enter the fraternity of the artist: the hunger, their manner of dress, their process and prayers. I’d brag that I was going to become an artist’s mistress one day. Nothing seemed more romantic to my young mind. I imagined myself as Frida to Diego, both muse and maker. I dreamed of meeting an artist to love and support and work with side by side.”

It was 1967 when Patti left Philadelphia for New York, a “real city, shifty and sexual.” She was only 20 years old. She had few friends and no money. She found shelter on park benches, in subways and in graveyards, and she relied on strangers for food. Observing that “Romanticism could not quench my need for food. Even Baudelaire needed to eat,” Patti found work at a bookstore. It was there that she met Robert Mapplethorpe.

Robert and Patti moved into a Brooklyn dive, and with no radio or television or money for entertainment, they spent long hours sitting side by side, sketching or telling stories. When they weren’t out earning money, they were at home creating. They would take turns at being the breadwinner: One would go out and find work so that the other could stay home and hone their art. Robert and Patti were poor but deliriously happy. They didn’t need anyone or anything but each other.

“We would visit art museums. There was only enough money for one ticket, so one of us would go in, look at the exhibits, and report back to the other.”

Patti and Robert formed an enviable partnership, one built wholly on trust and acceptance. They inspired each other and encouraged each other’s artistic and personal growth. Even years later, when Robert had come out as a homosexual and started hustling, they loved each other unconditionally and vowed to spend the rest of their lives creating and collaborating.

“Nobody sees as we do, Patti,” Robert said. Whenever he said things like that, for a magical space of time, it was as if we were the only two people in the world.”

In the summer of 1968, Patti moved out. Robert had become distant and irritable (“He never ceased to be affectionate to me, but he seemed troubled.”), and he informed her that he was going to San Francisco to find out who he was. If Patti didn’t travel with him, he threatened he would “turn homosexual.”

“There was nothing in our relationship that had prepared me for such a revelation. All of the signs that he had obliquely imparted I had interpreted as the evolution of his art. Not of his self. I was less than compassionate, a fact I came to regret… I felt I had failed him. I had thought a man turned homosexual when there was not the right woman to save him.”

Not long after Robert returned from San Francisco, they moved into the Chelsea Hotel, which Patti refers to as her ‘university.’ At the time, it was a community of poets and musicians and painters who had bartered their work for cheaper rent. Patti and Robert lived and learned alongside eccentrics who “had written, conversed and convulsed in these Victorian dollhouse rooms. So many transient souls had espoused, made a mark, and succumbed here.”

The Chelsea Hotel is only the beginning of Patti and Robert’s story. While Robert’s homosexuality eventually forced him and Patti to cease their sexual relationship and redefine their love, their creative partnership grew stronger than ever. They opened up their world to let other characters in and unknowingly created legends. As Patti recounts how she sat on the floor of Janis Joplin’s Chelsea Hotel suite, watching Kris Kristofferson serenade her with “Me and Bobby McGee”, she reflects:

“I was there for these moments, but so young and preoccupied by my own thoughts that I hardly recognized them as moments.”

She has now, and she’s recounted them so beautifully and vividly. Have you read Just Kids? Did you like it? Love it? You can buy the book here.

Comments

Wow!

This book has been on my “To Buy When I Get a Job” list since it came out.

Also, speaking of musicians and tumultuous relationships, Rilo Kiley just announced their break-up and I need someone to hold me while I cry about it.

Even though I don’t listen to them *holds*

I have been weepy about this all day. I mean, we knew it was coming, but everything is just so final now. I managed to get myself somewhat composed on the manner until my friend who was at The Elected show in San Francisco tonight texted me to say that Blake played Ripchord and said, “for my friends in Rilo Kiley. They’re not here, but this is for them.” And it just started all over again.

Lora, just borrow it from your local library :)

I’ve just put a hold on it. I’m no. 13 in line.

OMG. I just bought this, literally 5 hours ago, in London. Your review made me want to read it ASAP. I’m anticipating crying so I will have a box of Kleenex in hand.

WHAT. NO.

damn.

Apparently I don’t know how to reply properly. That was in response to the Rilo Kiley thing.

Whether you replied properly or not, it’s still a TRAVESTY OF EPIC PROPORTIONS.

I’m choosing to ignore the fact that their last album was kind of crappy and they haven’t made music in about five years and instead wallow in my sorrow.

This news is just too much for me to bare.

http://www.spinnermusic.co.uk/2011/07/13/rilo-kiley-blake-sennett-band-broken-up/

Oh dear me, I love that book so much. The opening bits about her seeing the swan slayed me, and yes, I was bawling pretty early on, too.

Much like she has always done with her poetry and her music, Patti draws pictures and wrenches feeling from even the most remote corners of one’s soul.

Patti has always been an inspiration to me, and with this book, has solidified her role in my life as a creative being. I’m sure many more will feel the same.

saw Patti Smith Live in Kent last week. She was incredible, better than the next three acts billed after her. Gotta get me a copy of this next :)

I love this book. Love love love it. Right now my girlfriend has my copy of it because it is too good for her not to read it. There’s just so much to love about this memoir. I especially appreciate how Patti Smith never seems to sugarcoat the difficulties of being poor and hungry, but still manages to capture the romance of the life of the starving artist. It’s just so good.

I loved the book and your review of it as well.I must confess that I was an ignorant kid who didn’t know much about Patti & Robert before but the book really touched me.And I was completely fascinated by her magnificent recounting of New York’s art scene of the 60s & 70s.

My mom keeps telling me to read this.

I didn’t know who Patti Smith was until you guys started talking about her but from the excerpts in this article she sounds like a writer’s writer. I’m going to check this book out.

i haven’t read it but now i want to.

NYC PEOPLE!

She’s throwing a free concert TOMORROW at Battery Park. 7pm.

Ahhhh, I want to read this like INSANITY.

I read it a while ago, mostly because it was A New Book About Gay People And Art and I’d just seen Mapplethorpe’s work in an exhibit. The beginning was kind of boring but it’s worth it to keep reading because it does get really interesting when she moves to New York and meets Robert. It’s also kind of amazing how many important cultural figures are part of her life in whatever way. It made me more grateful for being able to go to art school, instead of having to just leave home for New York without any place to stay.

Yeaaaah. I’m gonna go buy this now.

My gf got this for me recently and I started reading it at the bar one day after a particularly long day at work. It struck me from the very beginning. I’m still not done reading it yet but I would highly recommend it to all you queermos.

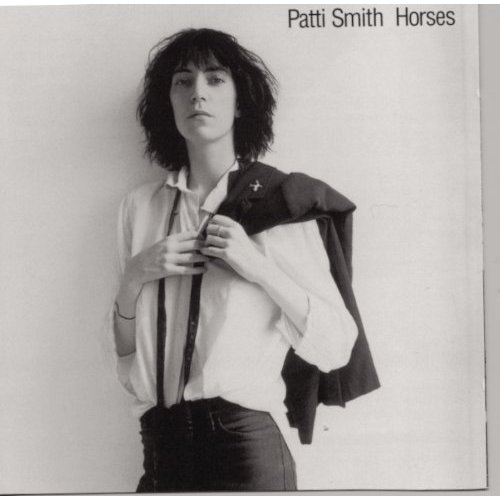

Beautifully written review, thanks. I picked this book up about six months ago and read it cover to cover over a weekend. My mum was a big Patti Smith fan and as a young gay kid I was always struck/ stunned/ thrilled by the androgyny of the Horses album cover (not to mention the armpit hair of the Easter cover!). I always wanted to take a closer look, but some how felt the need to flip quickly past them when searching through my parent’s albums.

One of the most interesting elements in the book for me was Patti’s response to Mapplethorpe’s sexuality. While she doesn’t say so explicitly, it seemed to me that she was very uneasy about Mapplethorpe’s homosexuality – understandable given it’s impact on their relationship, but it reminded me so much of my mother’s reaction to my sexuality. My mum was heavily involved in the feminist movement in the 70s and 80s and has many lesbian friends, but like Patti was raised catholic and took it quite seriously until she was in her late teens. She’s always been very supportive, great with my gfs etc., but still feels the need to “disclose” the fact that she has a gay daughter. I can’t quite describe it, but there’s a formality to it – respectful but distant and slightly uncomfortable. It’s weird as I’ve had gfs whose parents where very mainstream in comparison to my mum and yet are so much more relaxed about the gay child thing. I’m not sure, but I don’t think it’s homosexuality she’s uncomfortable with so much as sexuality… and having a gay daughter just puts the topic it right out there. Anyhow parts of this book felt so familiar from that point of view.

Also, if folks are interested in memoirs about gay artist kids in nyc in the ’70s, City Boy by Edmund White is also great.

I am all over this, brb buying a copy now.

I bought this after reading a jd samson interview in which she said she was reading it, and I cannot praise this book highly enough.

It is so affecting/life-changing that I haven’t seen the world the same since reading the first page. The fact that Patti & Robert live purely for arts’ sake, and not in a contrived Wildean way fills me with a strange blend of jealousy and hopefulness; I wish I could do the same, I really do. But we live in a different time now.

I really wish that I could have gone up to nyc to see her today, but seriously read this if you haven’t yet. Just Kids had me from the very beginning; it was so beautifully written and inspiring. And also, it made me feel a lot less “alone” because I found so much I related with what she wrote. Read it now!

I started reading this in January when my partner and I were living with nothing in Brooklyn. He got really sick and we had to fly to Florida. I read it allowed to him as he lay on the floor of the Newark airport.

I put it down. He got better. We resumed lives in college together. We grew distant. I picked the book up again on a recent trip where I fell in love with a city and artists and I broke up with my partner, because I’m looking for my Mapplethorpe. He just wasn’t.

This book made me cry. It made me sick. It made me laugh. It made me smile. If fucking made me.

This book is amazing. I have been a Patti fan since forever, and I absolutely loved this book.

FYI: If you ever have the chance to see Patti live, do it!

Fark! I have this book but I’m not even done with Dharma Bums yet!!!!!!! I read the first few pages but I felt obliged to finish reading DB. OBLIGATION. LOL.

Not to mention my 2 other books waiting in line. Oh well.

Thanks for this Crystal, great review. Must get hold of a copy!

Heard Ellen Page mentioned it was one of the books she’d just read in a recent interview.

Emma Watson was inspired by the book in a print interview.

Guess every one is reading it!

Emma Watson was at the Patti Smith concert in NYC last Thursday!

One of the most incredible books I’ve read all year.

I read it all one afternoon at my girlfriend’s apartment, she was sleeping with her head on my lap and a forgotten book in her hands and I just couldn’t stop, not even to think, to take it in properly. It still lives so strongly in me that I feel like it influences everything I do, all the decisions I make. I want to be someone now.

I read this book in five days. Adored it. Best biography ever.

Inspired me to actually write music, go to open mics, and take guitar lessons again.

SUCH a good book. Patti is my muse.

This is one of my FAVORITE books of all time. I’ve been a Patti Smith music fan for years, but this book has had a profound impact on me both as an artist and person. It’s such a beautiful intricate story about love, friendship, and following your heart. Patti Smith is a treasure. So happy you reviewed this book.

I know this is a super-late reply, but I just wanted to thank you for a lovely write up on this book. I spent late nights I didn’t have to finish it during my last term in school, and it was completely worth it. Such a beautiful and moving portrait of two friends and soulmates – definitely a favorite book.

I just finished this book 2 days ago (sobbed also) and I have been doing nothing but listening to her music and looking at photos of her and Robert since then.

I feel so materialistic compared to her and now I am rethinking so many things. I haven’t been this affected by something in so long. Glad you enjoyed also, great review.

[…] Bild via: http://www.autostraddle.com […]

[…] Bild via: http://www.autostraddle.com […]

[…] Bild via: http://www.autostraddle.com […]

[…] Patti Smith’s Just Kids belongs to lovers, artists and outcasts | Reading this gorgeous review had me running to the barn to dig out my copy of Patti Smith’s amazing autobiography, which tells the story of her years in the New York punk scene. […]