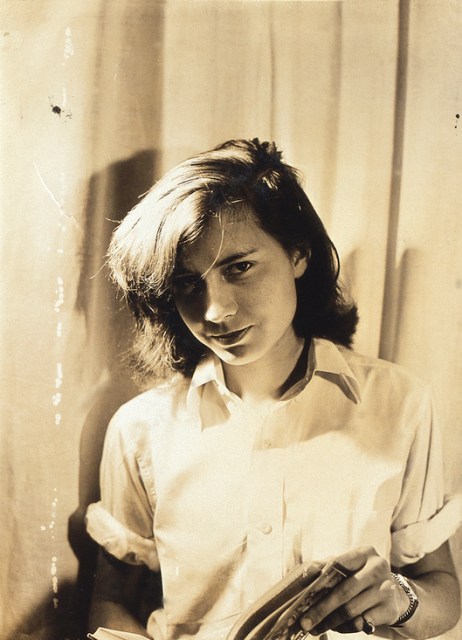

Featured image courtesy of Brian Douglas

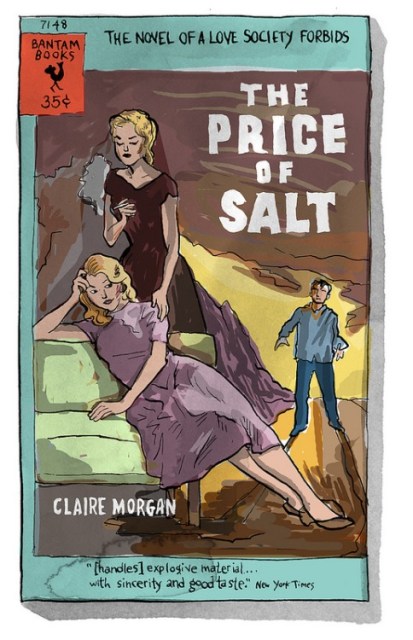

In the early 1950s, the Lavender Scare was in full swing, with Senators McCarthy and Peurifoy warning Congress of homosexuals infiltrating America’s creative and political organizations. The Mattachine Society — the first American gay rights organization — was formed in Los Angeles. Dr. Alfred Kinsey’s report on sexuality began revolutionizing the way we think about hooking up. And a Little Lesbian Pulp Fiction Novel That Could, written by Claire Morgan and priced around $0.50, hit drugstore stands.

Nearly forty years would pass before Patricia Highsmith (author of The Talented Mr. Ripley and Strangers on a Train) would admit to being the pseudonymous writer of this book, The Price of Salt. “The appeal of The Price of Salt was that it had a happy ending for its two main characters, or at least they were going to try to have a future together,” Highsmith wrote as an afterword for the novel’s 1990 reissue. “Prior to this book, homosexuals male and female in American novels had had to pay for their deviation by cutting their wrists, drowning themselves in a swimming pool, or by switching to heterosexuality, or by collapsing — alone and miserable and shunned — into a depression equal to hell.”

If you were a lesbian and wanted to write lovely stories about other lesbians in the 1950s, you could… but you’d have to jump through a hell of a lot of hoops. Not only did the first queer pulp fiction authors run the risk of tarnishing their own literary careers (hence Highsmith’s use of a pen name, Claire Morgan, when publishing The Price of Salt); their characters were restricted by harsh, unspoken guidelines. In a way, gay writers who were censored before their words were even written became pawns of the Red Scare, their work serving as anti-communist propaganda that sent a clear message: homosexuality had devastating consequences.

“They not only had to be punished,” lesbian pulp veteran Ann Bannon reiterated when discussing her own gay girl protagonists in 2012. “In order to shut up Senator McCarthy and all of the morality cops, they had to be punished because as a result of those guys, the Post Office would not deliver the books unless one of the women had committed suicide, gone nuts, or been killed.”

In the years since its first publication in 1952, The Price of Salt has done unusually well commercially (Highsmith stated that it had already sold a million copies by 1989; the book’s cover claims half of that amount), and many of today’s contemporary gay writers have cited it as a favorite, including The Miseducation of Cameron Post’s emily m. danforth and current Guggenheim fellow Alison Bechdel. Even the High Empress of Seriousness, Susan Sontag, adored Highsmith’s Sapphic paperback romance:

Something in the story – about a gifted (yet insecure) young woman who moves to Manhattan in the early 1950s to become a theatre designer and ends up falling rapturously in love with a glamorous, outré older woman – must have once struck a chord: Sontag seemed to dote on it.

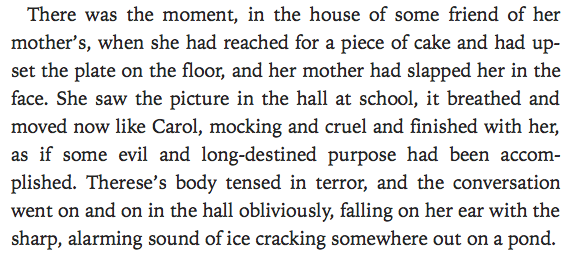

The Price of Salt is a classic because it offered the very first happy ending for lesbian couples, but also because the book is very well-written. Its 288 pages indulge the reader’s desire for lezzie drama and romance (“Then Carol slipped her arm under her neck, and all the length of their bodies touched fitting as if something had prearranged it…”) but also offer a uniquely Highsmith dose of mystery and tension:

Somewhere in Switzerland’s Cimitero di Tegna, Highsmith is rolling at her grave as her “dykey little potboiler” achieves another series of firsts: The Price of Salt is the first lesbian pulp to be made into a movie, and one with a multi-million dollar budget, a notable cast (Cate Blanchett, Rooney Mara, Sarah Paulson, Carrie Brownstein, Kyle Chandler), a three-time Oscar winning costume designer (Sandy Powell), an Emmy-nominated lesbian screenwriter (Phyllis Nagy) and talented director (Todd Haynes) at its helm. Titled Carol, the period film is set for release sometime in spring 2015.

As to be expected, there are a few differences between the book and movie. In Carol, Therese moonlights as a photographer instead of an aspiring theater set designer as she did in the novel. Sleater-Kinney’s Carrie Brownstein’s role as Genevieve Cantrell, a character who has an “encounter” with Therese, has been heavily edited down. But for the most part, Carol seems to stick closely to Highsmith’s original story. I’m looking forward to seeing Sarah Paulson play Carol’s know-it-all ex-lover Abby (who I hope will be as 100% tough, 0% cookie as Paulson’s Lana Winters in American Horror Story: Asylum). It should also be exciting to watch Kyle Chandler – who I’m all too accustomed to seeing decked out in empowering speeches and dad jeans as Coach Taylor in Friday Night Lights reruns – play a patriarchal villain.

Because Rooney Mara as a mousey Therese and Cate Blanchett as a femme fetale Carol are so undeniable and goshdarn pretty, it’s easy to forget that Carol is yet another film about homosexual women that is directed by a man. But that’s still important, particularly when this project has all the trappings of a blockbuster. It’s natural to want the film adaptation of one of the most important works of lesbian lit to do it justice. It’s also natural to be fiercely protective of narratives that intimately resemble our own stories of marginalization. And when the last two male-directed critically-acclaimed films exploring the vast terrain of lesbianism left some of us feeling like erotic Freudian doppelgängers and artistic products of the male gaze, it’s definitely natural for queer women to distrust the men who are essentially directing our lives: will they ever get it right?

Fortunately, director Todd Haynes excels at the queerly feminine. His previous subjects include a hodgepodge of housewives and glamorous pop stars, from Great Depression mamas with tons of gumption to a white woman in love with a black man during the Jim Crow era to Karen Carpenter and Ziggy Stardust. His willingness to take on stories that aren’t considered marketable speaks volumes, as are his creative partnerships with women like costume designer Sandy Powell and Cate Blanchett (whom Haynes also directed as Bob Dylan in I’m Not There). And for those to whom social justice cred matters, Haynes was a member of Gran Fury, the artist collective that worked on reproductive health-related visual campaigns at the height of the AIDS epidemic.

Women seem to be more than just colleagues and creative subjects for Haynes; they are also inspiration. In recent interviews, Haynes discussed how Carol has a rougher feel than his previous film that was set in the 1950s, and how he looked to midcentury New York City photographers like Ruth Orkin and (rumored lesbian) Vivian Maier for pointers:

You know, it’s set in the ’50s, and it’s a very different kind of ’50s film than Far from Heaven was. The feel of it is much less inspired by ’50s cinema, and more by, I guess, photojournalism and a lot of the art photography we were seeing at the time, which has much more gritty… it’s a very poised film, because it has a real sense of control to it. The look of it is much more distressed.

It’s set in the early ’50s, before the Eisenhower era had really taken hold. It was a really transformational and unstable time from the war years into the beginning to what would become the ’50s as we know them. The historical imagery and references we uncovered showed New York was really like an old-world city in great duress: very dirty, very dingy, and very neglected.

I thought it was such an interesting place to mount this, ultimately, very pure and simple love story between a younger woman and older woman at the most unexpected cultural moment and place.

Aside from a few folks who saw bits of Carol at Cannes this year or attended readings of the script, the word is still out on whether this will be the “lesbian Brokeback Mountain” that’s been talked about for years. Hopefully this adaptation go will further than that and become the Little Movie That Could to Highsmith’s Little Book That Could, going down in history as being a work of queer art so good that no one could deny it.