Think of the words “queer art.” Several faces may be coming to mind already. Amos Mac. Alison Bechdel. Divine. Zoe Strauss. Betty Parsons. Every person mentioned in Le Tigre’s “Hot Topic.”

Norman Rockwell is probably not one of those faces.

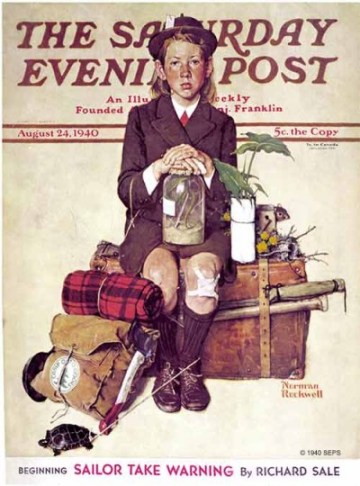

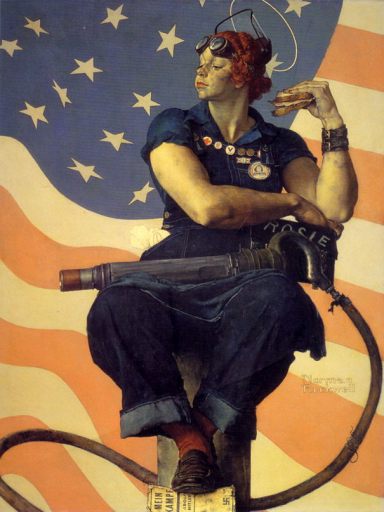

Born in 1894, Rockwell would live through two World Wars, the Civil Rights Movement and the first steps on the moon. His art depicts those times in a small town that could be Anywhere, USA. Today, his best-known works are a series of family portraits mirroring President Roosevelt’s Four Freedoms, his Boy Scout manual illustrations, and a pictorialization of America’s favorite butch lady: Rosie the Riveter.

Rockwell’s paintings center around the political, the patriotic, and the traditional–all concepts that queer art enjoys ripping to shreds, restitching into something radical, and topping off with a glittering, sparking bow.

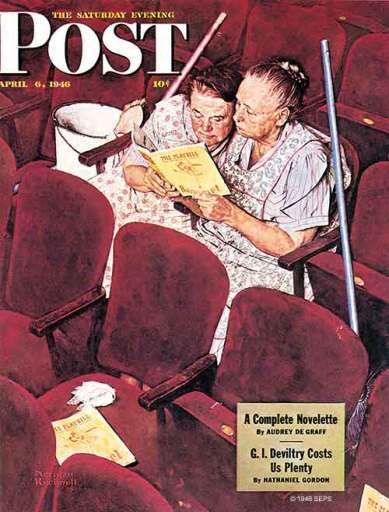

Yet his work is still undeniably…good. You don’t have love baseball and apple pie to appreciate Rockwell’s crazy talent. He was a wholesome storyteller who never had to utter a single word. Before color film became universal, Rockwell brought life to the American experience; each painting is a single priceless moment, freeze framed. As your eyes scan, picking up on little secondary details like a stretched-out sock or a intricate black eye, you feel as if you’re watching a movie instead of staring at hardened paint on a canvas. It’s magically cinematic. And if you look even closer, there’s some interesting commentary on gender. A decade before Rosie, Rockwell was painting the girls who were destined to become riveters.

Underneath all of the red, white and blue, there’s something a little queer going on.

While Norman Rockwell’s primary subjects were men, he also painted a lot of boyish girls. He was given hell for this, especially from other male artists. Coles Phillips once snarked at Rockwell:

Young men and boys. Haven’t you got any guts? You’re young. Haven’t you got any sex? Old men and boys. For Lord’s sake.

As did cartoonist Clyde Forsythe:

You can’t do a beautiful seductive woman. She looks like a tomboy who’s been scrubbed with a washcloth and pinned into a new dress by her mother.

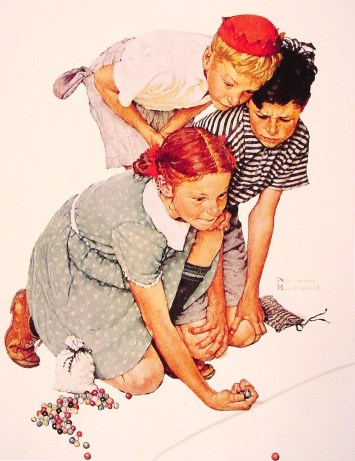

As queer people, we get that gender is never easy. It’s slippery and elusive. One minute, you’ll have it pinned down. The next, it’s slipped away like one of those awkwardly phallic water snake toys you might’ve owned as kid. Home From Camp makes me wonder if I was more certain of who I am when I was ten–scabbed knees and all–than I am now.

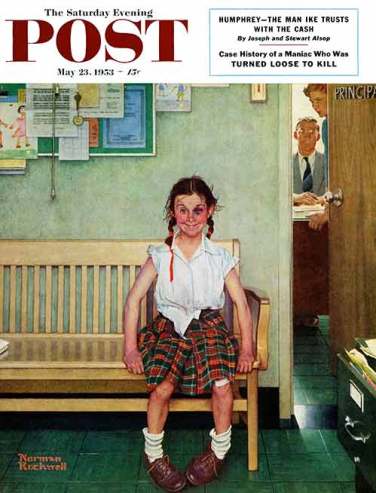

According to The Saturday Evening Post, “Rockwell loved the idea of a smug schoolgirl who bested her opponent in a fight.”

Rockwell was no stranger to juxtaposing adolescence with adulthood, but it’s really interesting to see this done with girlhood and womanhood. In Going Out, a grade school-aged girl and her puppy intently watch an older, unquestioningly feminine woman preen for an evening out. Is the girl looking at the woman with eagerness for the day she’s able to assume a similar role, or quiet desperation? Maybe she’s content with her life that consists of puppy dogs and pants. It depends on who you’re asking.

What one person might interpret as excitement for the trappings of womanhood, a genderqueer feminist might read as reluctance.

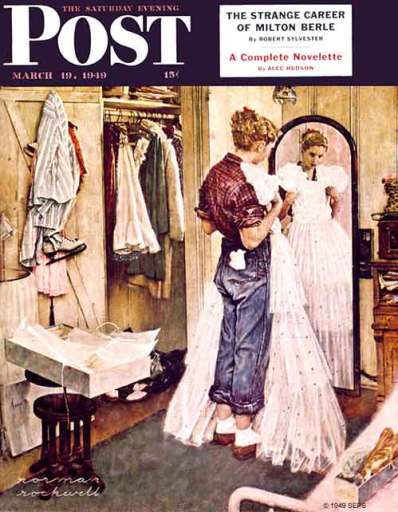

If any Rockwell portrait says, “I’m not a girl, not yet a [socially normative] woman,” it’s First Evening Gown. Part of art interpretation is projection, and I can’t help projecting all of my childhood memories of being made to wear a dress when I didn’t want to all over this painting; it’s the well-worn penny loafers the girl is wearing versus the crispness of the gown. Did the dress get thrust upon her? Did she beg and plead for the dress? It’s a coming-of-age story with no clear resolution.

“The artist captures the ‘in-between’ age well between the cast away doll and the closer ‘necessities’ of lipstick and hairbrush.” – The Saturday Evening Post

During the war effort, it didn’t matter if you were queer or a woman. If you were of able body, you went to work. A lot of Rosie’s butching up was situational, but no less heroic.

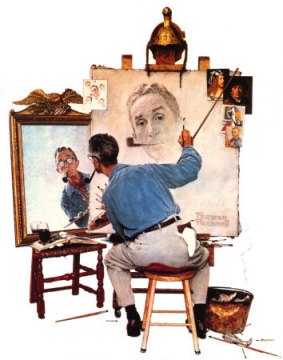

Perhaps Rockwell did have a sixth sense when it came to understanding gender. After all, at a gangly six feet tall and 140 pounds, the artist had firsthand experience with not fitting the mold. In the early 1900s, the “ideal American man” was a brawny guy with a farmer’s tan and crew cut. At 21, Rockwell was denied placement in the US Army because he was deemed underweight. When he was finally admitted, he was assigned artistic duties and never actually experienced the combat for which he’d yearned.

In Anywhere, America, gay is becoming increasingly more okay. If he were still around, how would Norman Rockwell paint our button noses, rainbow flags, and alternative lifestyle haircuts?