After the massacre in Newtown, Connecticut that killed 20 young children and seven adults, there’s no longer any delaying the national conversation about gun control. While there are other, larger conversations to be had – about how a culture of violence is fostered and how it can be healed, about what role access to mental health care plays in these incidents, about why the vast majority of mass shooters are white males – but the conversation that many people seem to be most ready to have is around how horrifically violent incidents like the Sandy Hook shooting are made possible by America’s current laws around access to firearms. Today, Barack Obama made his most promising statement to date about gun control legislation — which we’ll get to in a minute.

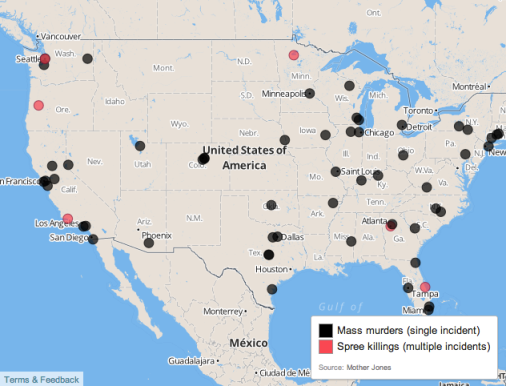

Although originally published this July, Mother Jones’ comprehensive analysis of mass shootings in recent US history is newly relevant. In the incidents they looked at between 1982 and 2012, 79% of the shooters accessed their weapons legally. The shootings occurred all over the country, making it clear that the factors leading to these incidents can’t be isolated to a particular region or community.

Our Past and Present with Guns

Mother Jones’ coverage has continued, analyzing not only the shootings themselves but drawing conclusions about what they mean in terms of how we can try to make sense of the senseless and make our future look different. One of those conclusions is that in the 62 shootings over the last 30 years, not a single violent shooter was stopped by a civilian with a gun. This includes some states where citizens can be granted lawful concealed carry permits – like in Colorado, where the Aurora shooter bought his weapon legally. Colorado also explicitly allows carrying concealed weapons on college campuses. And while Colorado’s requirements for a concealed carry permit demand that an applicant be a resident, pass a background check, and not be addicted to controlled substances, plenty of other states are much less stringent. In Virginia, an online test qualifies as firearms safety training. In Missouri, civilians can legally fire a gun when intoxicated if it’s in self-defense. Regardless of the legal ease with which residents of any of these states can exercise access to and use of firearms, the mass shootings in Virginia and Colorado continued without intervention by an armed citizen.

Gun rights enthusiasts might argue that all these avenues of access to guns are well within the rights of an American citizen. But not all guns are created equal, and neither is access to them. The guns most heavily featured in recent mass shootings are semiautomatic handguns and assault weapons, which are generally used for military and law enforcement purposes. Limiting access to these weapons wouldn’t affect those people who use firearms for, say, hunting. Semiautomatic handguns and assault weapons are created for the express purpose of hurting and killing other humans; as has been expressed countless times in the past week, it’s perhaps shocking that our country needs to be pushed so hard before considering why such a high number of average citizens should feel the need to own them – and why our government feels that they should be provided.

It’s shocking that it’s taken this long because aside from the 62 mass shootings that have occurred in the last 30 years, the United States also has a homicide by firearm rate of 3.2 per 100,000 citizens. That may not sound like much, but the rate for Switzerland, which has half as many civilian firearms per 100 citizens (46 to the US’s 89) is only 0.7. Even without looking at mass shootings, a shocking number of people – individual people – in the US are killed by guns. 60% of the US’s homicides are committed with a firearm, which in some ways may create a sense of desensitization. When we grieve over a murder like Trayvon Martin‘s, we sometimes forget that we’re not just grieving over a murder, but specifically a shooting. George Zimmerman isn’t just a man who believed that he could reasonably need to perform “self-defense” against a 13-year-old because he was black and wearing a hoodie. Zimmerman is a man who genuinely believed that, and who legally obtained and carried a semiautomatic weapon – a model popular for concealed carry.

What’s interesting is that while many feel that Zimmerman’s (and, legally, Adam Lanza’s) right to own and operate firearms is inalienable, this wouldn’t be true in most other places and times. First of all, the US’s history of gun control shows that access to firearms was much more restricted for most of our history as a nation. In fact, Congress passed a bill making it illegal to own or transfer most semiautomatic weapons in 1994, but that bill expired in 2004 and hasn’t been resurrected. Since then, access to firearms has only gotten easier. Requirements for training or experience haven’t increased along with greater access – requirements on competency with firearms can be lax depending upon the state and the firearm, and in some sales of firearms – for instance, those sales made by private citizens or at a gun show – don’t legally need a background check, depending on the state.

Although private citizens often have access to a similar grade of weapon as is used by professional law enforcement officers, the difference between what we expect of a law enforcement officer and a private citizen when it comes to a gun is striking. A law enforcement officer uses a gun after intensive training and education about both the use of their gun and when its use is appropriate; every time a law enforcement officer discharges their weapon, the state has a right to hold them accountable for its discharge, and punish them if the weapon’s use wasn’t called for. In contrast, many of the guns owned by private citizens aren’t even registered, and the experience with and respect for firearms that are required to obtain them are often laughable. Why would we expect untrained private citizens to behave more responsibly with firearms than professional law enforcement officers?

Other Ways of Doing Guns and Gun Control

Other countries certainly don’t. While the US comprises only about 5% of the world’s population, it makes up 42% of the world’s privately owned firearms. It seems not coincidental that the rate of homicide by firearm is 200-800% higher in the US than in developed countries with stricter gun control laws, like the UK or Japan. Of course, countries like the UK and Japan differ from the US wildly in terms of history, culture, and political construction – America’s relationship with guns is deeply intertwined with our genesis as a country born from armed revolution, with our cultural emphasis on individuality and self-sufficiency, and our complicated national narrative around states’ rights and the extent to which government powers should reach. All of these factors and more should be taken into account when comparing gun control in other countries to that of the US.

But that said, it’s instructive to look at how accessing firearms works in England. Applicants for firearms are required to explain exactly why they want a gun, and are told they need to provide a “good reason;” guns which are designed to be use for a specific purpose require an explanation of why one needs that model in particular. In a drastic contrast to the US’s system, gun applicants are essentially asked to “[prove] to police officers that you are not a danger to society… In short, it has been designed to put as many barriers in the way as possible and to assume the worst, rather than hope for the best.”

The UK’s remarkably strict laws haven’t eliminated all gun violence. The shooting in Cumbria in June of 2010 were perpetrated by Derrick Bird, who had obtained his firearm completely legally, jumping through every hoop that the application process set out for him. But the hoops that Bird had to jump through were in direct and considered response to other tragedies before him: a massacre of 16 people which led to the ban of semiautomatic rifles, and a massacre of 16 schoolchildren which led to the banning of all handguns. The sweeping firearm reforms that took place after the 1996 shooting of schoolchildren in Dunblane also included firearms amnesties, in which thousands of firearms were given up. If anyone is now found possessing illegal firearms, the punishments include up to ten years of prison time.

In contrast to the US, so heavily invested in its gun culture, the public in the UK generally supported and cooperated with the ban, viewing it as necessary and appropriate. Although the rate of gun crimes initially showed little change, crimes involving handguns eventually dropped by 44% between 2002 and 2011. Although firearms amnesties would likely be understood as the storied fear of a federal government coming to “take away our guns,” it might be one of the only effective solutions to the already enormous amount of firearms in circulation in the US. Although stopping their sale from official points of purchase would be a start, there are already about 88 firearms to every 100 Americans, and those guns wouldn’t magically disappear.

At the time of the Cumbria shooting, the UK was also working on how to combat the “criminal conversion of imitation firearms” – so, locking down illegal access to firearms as well as legal access – and working to create a dynamic interaction between the police force and the healthcare system to keep doctors informed of whether their unstable or potentially suicidal patients have firearms in the home. While the cultural and political differences between the US and the UK may not make all of those changes feasible for the US, at least one major difference is notable: the UK responded directly to each of their mass shootings, while the US has had seven mass shootings in the last year alone, and gun ownership is now easier than ever. Similarly, Japan has banned almost all forms of private gun ownership, and has reduced its firearms homicide rate to as low as two a year. There are dozens of reasons why those differences exist; it’s misleading to hang all our fears and hopes about violence to gun control, and the cultural and political differences between these two countries and the US mean that their methods may or may not be as effective here. But the most notable difference is that they’ve done something.

What Could Happen Next

It’s beginning to seem like the senseless murder of 20 children in the place where they were supposed to learn about consonants and vowels may be the push which allows the US to change something as well. Even the NRA has made a statement promising that it is “prepared to offer meaningful contributions to help make sure this never happens again,” although it’s not clear what those contributions will be until their press conference on Friday.

President Obama has already begun offering up his support for a variety of changes. He’s said he would actively support a reinstatement on the ban on assault weapons, and promises that that ban is part of a “wide-ranging effort” which is “taking shape.” The President may also be “willing to consider limiting the capacity of ammunition magazines and closing a loophole allowing individuals to purchase firearms at gun shows without a background check.” Obama has promised to make gun control a “central issue” in his second term, and will be presenting his plan to Congress no later than January.

Obama also plans to address issues of access to mental healthcare, saying, “We are going to need to work on making access to mental health care at least as easy as access to guns.” It’s important to note, also, that the ideas introduced by Obama will be legislative, which means that no matter how much he supports them, Congress has to also. There’s significant doubt about whether the House of Republicans will support reinstating the assault weapons ban, even if Obama and many citizens do. The incoming chairman of the House Judiciary Committee has already said that “We’re going to take a look at what happened there and what can be done to help avoid it in the future, but gun control is not going to be something that I would support.”

What are the possible plans being considered? To the disappointment of some, it’s very unlikely that a sweeping change like the laws in place in Japan or the UK will come about. The Supreme Court has fairly clearly demonstrated that Americans have a constitutional right to own handguns. It seems very likely that any change in US laws on gun ownership will come in terms of specific guns and specific groups of gun owners, rather than a fundamental shift in policy which might lead us to a situation like the UK’s, where any applicant for gun ownership is assumed unqualified until proven otherwise. In NPR’s excellent breakdown of the legislative situation, they explain that the major questions at stake will be “who should be allowed to buy guns, how should they be allowed to buy them and what should they be allowed to buy?”

Some changes can be made without stepping on actual gun control toes; for instance, better updated and more comprehensive mental health records could make it easier to restrict gun sales to the mentally ill. But there’s significant roadblocks even in this area; for instance, last year the House passed a bill that blocks the Department of Veterans from designating a veteran as mentally incompetent for gun ownership, leaving that decision up to a judge instead. The “loopholes” Obama is talking about, which make it possible for up to 40% of gun sales to be made without background checks, are also on the list of priorities, but many other attempts to close them have already failed, and the momentum of Sandy Hook may not be enough to push it forward this time. It’s not clear whether the assault weapons ban will be able to hold water, either, in the face of the House and the powerful gun lobby. Another approach, which would be to limit the clip size available for firearms, could potentially be more palatable, but there are no guarantees.

Pro-gun politicians are suggesting that the post-Newtown focus should be solely on preventing “mentally ill” people from getting guns, but in addition to the obvious stigmatizing of a broad swath of U.S. citizens, it’s incredibly problematic to declare all “mentally ill” persons less qualified to own guns than those without diagnosed mental health issues. In fact, only about 4 percent of violence in the United States can be attributed to people with mental illness. Substance abuse is a far greater predictor of violence. According to Richard. A. Friedman in the New York Times, although “it’s possible that preventing people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and other serious mental illnesses from getting guns might decrease the risk of mass killings,” it’s worth noting “mass killings are very rare events, and because people with mental illness contribute so little to overall violence, these measures would have little impact on everyday firearm-related killings.” Shoddy science has already spread over the internet about Adam Lanza’s possible Aspergers diagnosis playing a role in the killings, but there is absolutely no link whatsoever between Aspergers and violence.

Ultimately, even those experts whom acknowledge the need for drastic change around our country’s relationship with firearms remain somewhat skeptical. Sweeping changes are unlikely to survive the intensely partisan atmosphere of Congress, which as so far been unable to agree on even such seemingly no-brainer pieces of legislation as the Violence Against Women Act. And even if they did, the legislation at hand is somewhat piecemeal.

As Harry L. Wilson, director of the Institute for Policy and Opinion Research at Roanoke College, explains for NPR, many mass shooters (and shooters of individuals) have been able to pass background checks. If a shooter is experienced, they can easily and quickly reload a more traditional weapon and fire many rounds in a short period of time if assault weapons are banned. And while certainly increased background checks on those buying weapons seem like a good idea, there’s a limit to how helpful they might be, and how helpful they’ve been in the past. Adam Lanza was, in fact, turned off by the three-day waiting period and instead just went ahead and used those that belonged to his mother, another legal owner. Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold of the Columbine shooting were too young to buy guns at a gun show in 1998, so they returned the next day with an 18-year-old female friend to buy guns for them. Even if individuals are subject to background checks, that may not be effective in changing the larger reality that there are guns everywhere in America, and plenty are available without going through the process of formally purchasing one. If gun enthusiasts react to the threat of new gun control legislation by stockpiling the weapons that are currently available, the problem might actually be exacerbated.

The chances that America is ready to adopt an outlook on guns like Japan, which seems like it might be the only absolute solution to the problem of the constant potential for senseless violence, are slim. Which means that, if we acknowledge that we probably can’t look forward to a nation which doesn’t have close to as many civilian-owned guns as it does citizens, we also need to start looking at how to address the systemic culture of violence and underlying factors that make us not just a nation full of guns, but a nation full of people who want desperately to use them.

Comments

This was a very well thought out and written article on the topic. It’s so hard to address something like this. I wrote my senators and representative and in reply from one of them received a response touting the importance of the 2nd amendment.

I totally respect the 2nd amendment, but at the same time I can’t figure why any ordinary citizen needs to own a semi-automatic or assault weapon. I’ve fired an assault weapon before…the sense of power it gives is actually quite terrifying….and I know that I do not want the crazy mass-murderers of the world to get their hands on a weapon like that.

Sure, if someone really wants to shoot up a building they’ll find a way to illegally acquire a gun…but it looks past the obvious point of how easy is it to legally get one now. We at least have to find a way to slow these people down.

People always cite the 2nd amendment without thinking about what guns were like when the constitution was written. You had to reload after one shot. Pretty sure the authors of the constitution did not forsee semi-automatic assault rifles.

yes. but really, does it even matter what kind of gun or how many shots/rounds? i don’t get the 2nd amendment. I don’t get why anybody should be allowed to own a gun for fun/self protection/etc. the german weapons act makes it quite hard to own a gun and I haven’t heard anybody complain about that. guns are stupid.

To be quite honest, it is still too easy to own a gun in Germany and there are lots of people complaining about strict gun control. There was so much talk about changing the Waffengesetz after Winnenden, but not much has happened becaue the German weapons lobby is pretty influential too. The changes after Erfurt were minimal too.

Like you, I believe that no one should privately own a gun or at least that no one should be allowed to keep both gun and ammunition in the house. But Germany is really not perfect in this regard either. (This is a pretty good documentary, if you want to check it out: http://www.wdr.de/tv/diestory/sendungsbeitraege/2012/0625/waffen.jsp)

thanks, I’ll watch that.looks interesting. but still, maybe it’s just me but what I’ve seen/heard/experienced re weapons in germany stands in no comparison to what I’ve experienced in the states. I might just had bad luck w/ the gun crazy host family I stayed with when 16

It certainly feels worse here. But I am sometimes afraid that people in Europe (including myself) just point at the U.S. as the really bad example and then forget that we have to tackle our own problems as well.

That being said, after Winnenden more than 130,000 weapons were voluntarily handed over to the authorities and then destroyed – so the culture back home is certainly very, very different…

Well written piece about an insanely complicated issue.

Australia’s story is, I think, another instructive example of what’s possible: http://www.slate.com/blogs/crime/2012/12/16/gun_control_after_connecticut_shooting_could_australia_s_laws_provide_a.html

Of course, as you suggested at the end of the article, what it comes down to is this massively ingrained culture of fear in the U.S. – and finding ways to overcome it will be long and difficult.

I read that slate article the other day and I think its a really good, concise summary of what happened in Australia.

As an Australian growing up in a post Port-Arthur environment, the idea that a private citizen (outside of farmers in rural areas) would have a need to have a firearm is incomprehensible.

Noone that I know has a gun (to my knowledge). The idea that normal people could walk the streets holding guns legally is terrifying.

it really struck me when I was reading the comments on the other piece about Sandy Hook and Riese said it never occurred to her that people lived in a world without gun violence.

It never occurred to me that people in first world countries did live in fear of gun violence. I thought that was happened in countries that were corrupt and run by drug cartels and gangs.

Totally. I don’t even understand what it is to live your life in the knowledge that the dude or lady on the bus or the train might have the means to kill you in their pocket. Who do you think of carrying a gun on a city street? I think of a police officer.

This is one of the most unfair pieces of anti-gun-nut babble I have ever read! Rachel I truly hope you are ashamed of yourself.

Why not try giving the whole truth instead of blending omitions and half truth?.

Did you not feel it important when talking about “assault weapons” then bringing up Swiss gun stats to mention that Swiss civilians are armed to the teeth with for auto military grade true assault rifles? Hell those in the Swiss military are required to keep their issued weapon at home! Yet, still maintaining a low crime rate?

Did you not feel it wasn’t important to mention that a very high percentage of mass shoolings happen in “gun free zones” where civilians CANNOT carry firearms? How can a person stop a mass killer if they are not allowed to be armed?

How about pointing out that the UK non-firearm related murder rate went way up? I guess the brits remembered that they can kill in other ways?

What about pointing out when it comes to gun control in the US, EVERYTIME a state opens up concealed carry the violent crime rate drops 15+% or even into the 30% range?

How come you didn’t feel the need to point out handguns are used for hunting all the time and there are a huge number of competitions all over the US and the world expressly for handgun shooters? I guess they’re not only made for shooting people after all.

Here’s an interesting one. Why LIE and say a semi-automatic rifle is an “assault weapon”, when an assault ifle has a fuly automatic capability? Semi-automatic rifles are not military type assault weapons they can’t be. Stop misleading people.

Oh, and what the hell does this have to do with queer culture? This site screams left and right about our rights in the LGBT community, then an anti-gun-nut starts screaming about taking away rights for everyone, WTF?

I could rant on and on, but I’m about to rip my hair out I’m so upset by this hatchet piece right now.

where exactly are you getting your “facts?”

I would also be interested in seeing your sources for these facts. Having lived in the UK and Germany for most of my life and now living in the US, I can tell you that I felt safer in the countries where only a few people have guns at home.

I have also done quite a bit of research on domestic violence in Germany and the U.S., and I can tell you that a lot more of the incidents in the U.S. end with a death. Why? Because when you need to strangle someone or stab them, the victim has a much higher chance of survival since these ways of killing require a lot more strength and resolve than pulling the trigger. And these domestic violence disputes can happen to anyone, not just the “bad guys”. Should both partners just sleep with a gun under their pillow?

Also, since it is apparently so much safer to be armed: when would you start arming people? At five, at ten, at fourteen? Why should there be age limits that expose 14 year-olds to the risk of becoming an “easy victim”?

I know gun control is a sensitive issue and I am obviously not American and don’t want to sound too judgmental. It’s not my culture here and it is, of course, up to America to resolve this issue. But I would love to see you give the sources to your statements. (Just for your information: here is an article about the vast decline of the murder rate in the UK in 2011 (550 homicides) – I believe their gun laws are still just as strict: http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2012/jul/19/murder-rate-falls-crime-figures)

And by the way, calling some a “nut” is the fastest way to discredit your own arguments.

similarly, stabbing or strangling somebody requires a much greater emotional investment.

there are most definitely other factors at play; but consider this, on the same day as the newton attacks 22 children were stabbed outside an elementary school in china. none of them died. what if he’d had a gun? what if he’d had the ammunition used in the newton attack? there absolutely would have been deaths.

by restricting access to assault rifles and handguns, and by restricting clip capacities, there will definitely be a decline in deaths associated with mass shootings.

in an ideal world, there would be no guns.

yeah i’d love to see these facts/stats too…

we all need guns to protect ourselves from other people with guns? doesn’t it seem like we’re attacking this problem from the wrong end?

also not everybody in this country WANTS to shoot people, or knows how, or wants to learn… or even has the physical ability to shoot a gun. i don’t want it to be every man for himself, like it’s on us to protect ourselves from violent criminals. we should all be figuring out how to prevent those crimes from happening in the first place.

The whole argument that you need a gun to protect yourself from people with guns is ludicrous to me. Once you get into an arms race–trying to outdo your potential enemies in the firepower stakes–the only person who wins is the arms dealer.

Yeah I kind of cringed when Switzerland was brought up as an example. For anyone who’s not familiar with Swiss gun culture, here’s an intro: http://world.time.com/2012/12/20/the-swiss-difference-a-gun-culture-that-works/. Obviously, there’s a number of differences between Switzerland and the U.S.; for example, the article states that all concealed carry is banned in Switzerland, while it is proliferate in many U.S. states and is the solution often touted for preventing tragedies like mass shootings. But the tradition of firearm ownership for defense and sport runs very deep in Switzerland.

I read and I read and I read on this subject and I can’t even begin to figure out what I’d like to say about this article. Mostly because debate on this topic is just so ugly and high-quality, unbiased data is hard to find. For the commenter who wanted some examples of thwarted school shootings by armed citizens, there’s a few listed in this article: http://news.yahoo.com/know-stop-school-shootings-003203357.html and yes I know gross it’s an article written by Ann Coulter but the examples she provides of thwarted school shootings are all factual. I guess my feelings come down to this: I can’t expect every citizen out there who carries a weapon to be able to use that weapon to defend against a mass shooter situation like Sandy Hook or the Aurora theater shooting. However, there’s stories out everyday of responsible U.S. citizens exercising their right to bear arms who have been able to thwart crime and protect themselves, their loved ones, and innocent bystanders. Also, in defense of semi-automatic pistols, they can have a LOT of advantages over revolvers, including easier concealability, lighter weight, and more customization options (which can make a gun much safer for the operator and those that might be around when it is in use).

“Rachel I truly hope you are ashamed of yourself.” that’s where I stopped reading your comment

Um. I’m pretty sure non-firearm related crime didn’t go UP in the UK. Rather, because there was little to no gun crime, knife crime etc became a larger PERCENTAGE of the crime stats. But I don’t think the actual numbers increased by a statistically significant amount by any stretch of the imagination.

Also, as other people have pointed out, you’re much more likely to be killed by a gun attack than a knife attack.

Although I also don’t have exact statistics to hand, so I can’t be certain. However, I couldn’t disagree more with Alison. I thought it was a great article.

Excellent article, Rachel!

Very interesting! I love the political pieces that you post, Rachel- they always help me better understand these very complex issues.

I would like to see more programs that give incentives to people to give up their guns. Tax breaks, a check, even grocery vouchers for their ammunition and weapons, even; perhaps it will take at least a few guns off the streets, especially out of the hands of desperate people.

I also looked into getting a taser recently for self protection, and found that they are illegal in many states. How is it logical to make non-lethal weapons illegal, but not lethal weapons like guns? And despite what people say, I can’t see any reason for a person to own 30+ guns or their own AK-47 or M-16. It’s just absurd. I mean, as a woman, I kind of get the whole “I feel the need to protect myself” impetus behind buying a gun. But there really need to be limitations on what you can buy and how many you can buy, and who can buy. It is way too easy to get a gun, and I think we should adopt Britain’s viewpoint of “Let’s assume the worst” instead of our old standby, “Let’s assume the best.”

And while I am actually kind of moderate when it comes to gun control (although I’ve been getting flak for it on Facebook as if I said, “Take away all their guns and destroy them, NOW!”), I really cannot get over the petulant whining I’ve seen coming from grown men who are afraid Obama will take away their huge cache of guns and assault rifles. Children died, you crybabies, can you at least not relent a little bit? It’s just disgusting.

This is a really nicely written article, Rachel, that covers a lot of points some of my anti-gun control friends like to bring up. It’s super interesting how you brought in gun control outside of the US, though. America needs to realize there are things it can learn from other countries. Go USA!

People can’t seem to understand the idea that if guns are banned MORE people will die. Armed civilians save far more lives than unarmed civilians.

Unarming people will get more people killed. The number one thing criminals say they are afraid of is an armed victim. Depending on which study the police are third or fourth on the fear list.

People bring up how good it is to point out how the UK gun ban stopped gun violence in the UK, how come no one brings up the sky rocket of home invasions, and other very violent crimes in the UK after the ban?

“People bring up how good it is to point out how the UK gun ban stopped gun violence in the UK, how come no one brings up the sky rocket of home invasions, and other very violent crimes in the UK after the ban?”

Not true. According to the British Crime Survey: “The increase in violent crime recorded by police, in contrast to estimates provided from the BCS, appears to be largely due to increased recording by police forces. Taking into account recording changes, the real trend in violence against the person in 2001/02 is estimated to have been a reduction of around five percent.”

There have also been multiple studies that show keeping guns in the home increases the risk of being a victim of homicide or that someone will commit suicide.

Also after Australia introduced its gun laws (banning automatic and semi automatic weapons) we experienced a significant drop in armed robberies and almost no change in the rate of home invasions. We also had a drop in the rate of firearm deaths and have not had a single mass shooting since the laws were introduced (we had 11 in the decade prior to the new laws.)

Very interesting article, but I have some points I’d like to make.

“…semiautomatic handguns and assault weapons, which are generally used for military and law enforcement purposes. Limiting access to these weapons wouldn’t affect those people who use firearms for, say, hunting.”

I respectfully disagree. An assault weapon, as Alison has already pointed out, is fully automatic (meaning 1 trigger pull = multiple bullets) not semi-automatic, which is what the majority of Americans own (1 trigger pull = 1 bullet). There is NO mechanical difference between a civilian AR platform rifle and a hunting rifle. The difference is purely cosmetic and ergonomic. And of course you can hunt with a handgun, but target shooting is also a completely legitimate sport.

What happened in Connecticut is a tragedy and it is time to have a conversation about gun control. But not banning guns or types of guns just because the way they look makes people uncomfortable. I’m all for requiring gun safety courses and education for gun owners, I’m even ok with requiring guns be registered (we register our cars and our dogs, too, after all). Gun control should be about making firearm use safer, not trying to prevent people from owning guns.

And Lora, there’s no reason to own 30+ guns. There’s no reason to own 30 teacups or 30 vintage pairs of shoes or 30 cuckoo clocks, either. People have collections. Firearms are intricate and often beautifully made and unique mechanical devices. When you have a collection, you can appreciate the differences in each.

That’s really all I wanted to say. Gun violence (violence in general) is a major problem in our society and we need to address it, but we also need to get over our knee jerk reaction that banning guns will make it all better. Banning guns would be about as effective at stopping violence as banning cocaine has been at stopping drug addiction.

“Banning guns would be about as effective at stopping violence as banning cocaine has been at stopping drug addiction.”

What makes you think that? I don’t know that the situations parallel at all. The cocaine to drug addition path goes “someone owns cocaine, whose ostensible purpose is to consume for personal pleasure. they use that cocaine for its intended use. when they use too much, they become addicted, which harms themselves most directly, and society or other people indirectly.” The gun ownership to violence path goes “someone owns a gun, whose ostensible purpose is to either display on the wall like a teacup, shoot inanimate targets, or kill animals with. they use that gun for not its sanctioned purpose, and instead for killing other human beings. This harms other human beings most directly, and themselves and society indirectly. There is neither a quantity nor physical addiction factor involved.”

While comparisons don’t have to be identical on every point, I think the differences between these two things undermine the conclusion you’re trying to draw.

The rest of the points you make are reasonable, even if I don’t agree with them, but I think this conclusion isn’t sound at all.

With drugs, there’s also the fact that they’re a lot easier to manufacture or grow in your backyard (not so much with cocaine, but definitely with marijuana, meth, etc.) You can’t manufacture a gun in your backyard. And while people talk about illegal gun cartels as though they’re the same as cocaine cartels, most illegal guns in the U.S. are ones that someone along the line bought here legally. It’s a case of getting it from a friend without a background check, or stealing it from a store – not so much of getting it from illegal gun dealers. In those two former cases, the existence of legal guns make it easier for people to acquire illegal guns.

Very well written article. It’s always good to understand the reverse side of social issues. You made a good point about education and safety as well. I feel like if they held civilians to the same standard that they hold the military or our police forces we’d be better off, but I don’t quite agree that gun control is the solution.

I am in the army, and before we’re even given a weapon we have safety, proper technique, and more safety drilled into our heads for weeks. In many areas we are required to hold our weapons in an armory, somewhere separate, that we can pull from whenever we like, but the weapon is at the least secure. I know many people who own their own handguns and “assault weapons” and these aren’t people who would even dream of killing another human being (unless in war, but that’s a different story). Owning a weapon brings a sense of independence and confidence. Knowing that whatever happens you know how to protect yourself and your loved ones (in any sort of medium) is reassuring at the least. I say let them have their guns, but at least make sure the proper measures are in place so that people who shouldn’t have them, don’t.

Unfortunately, the world is full of people seeking to do harm. I don’t think new gun restriction is going to stop them. it might slow them down, they might have to get more creative, but I’m a firm believer that anyone with a strong intention to do something will get it done and that can be in a good way or a bad way. To be human is to be terribly amazing, with all the potential in the world and only a choice to decide where that potential will go.

*drops the mike*

Dear friends,

I just wanted to let you know that if any one of you was ever in danger of being shot/raped/stabbed/killed/threatened in a way that made you fear for your life, I would use one of my semi automatic handguns to protect you even though you don’t believe I should have it. I’ll bet that story would change real quick.

In addition, If you all would still like to stick with your stories, I regret to say that I absolutely will still continue to defend your saftey and the saftey of my fellow citizens with my guns if the need arose.

Sincerely,

A responsible gun owner

How come so many survivors of school shootings or the families of the dead are then rallying for more gun control? Shouldn’t their story have changed according to your logic?

Their stories have changed. Look around hundreds of potential school shootings are thwarted every single year by responsible gun owners yet the media NEVER reports those cases. Person comes to school to harm kids. goes to car and gets his/her gun. Guess what? No school shooting. No report. Sadly our culture lets us know about the sinners and not the saints. I beg you to look up thwarted school shootings bc someone else had a gun. I would give you links but I’m on my phone and can’t do it from here. Thank you.

I’m on my phone as well, but happy to wait for links that report school shootings that were apprehended by PRIVATE gun owners, using their guns to stop the potential shooter.

yeah, i googled it and came up short, so i’d love to see those links.

this article covers more than 120 thwarted school shootings:

http://www.kshb.com/dpp/news/national/more-than-120-school-shooting-plots-thwarted-in-us

none were thwarted by private gun owners. they were stopped because authorities heard about threats being made or somebody saw somebody else with a weapon. or authorities came and took care of it. never has somebody walked into a school to shoot a bunch of kids and then been thwarted after being shot by a private gun owner.

learning how to shoot shouldn’t be a pre-req for somebody to become a teacher. teachers have enough to worry about without being called upon to shoot people at a moment’s notice and be held accountable for doing or not doing so.

I don’t think that we’ll be able to have any significant legislation to pass through because everything will include a grandfather clause meaning if you had it before the law went into effect you get to keep it. That being said, I still think that guns should be registered, even in the military you have to have your guns registered with the MPs and there are requirements for a certain number of locks required in your house. I also think that if registration is required, the background check loophole at gun shows would play into that. My pro-gun rights roommate says that people will still get them from person to person transactions, but even with these two changes they wouldn’t hurt the gun rights activists and could only be a positive to the general public. I also think that there is no legitimate reason for high capacity magazines except as a collector’s item so they can be put under the same “class 3 license” requirement along with silencers and machine guns.

Dear readers,

Please check up on your facts and understand that every responsible and educated gun owner knows that she must register her guns with the government upon purchase. Yes, people still get stuff from person to person sale but the government still knows the original person who bought it no longer owns it and sold it to someone else. If any of you know ways to purchase guns that the government does not know about please let me know your avenues because in all honesty I am against big government. Kthanksbye :)

Yeah, that’s not really true, a lot of this varies by state. It’s pretty easy to buy a gun at a gun show without a background check.

And you’ve still yet to demonstrate why even “responsible” gun owners need to own semi-automatic weapons. If your purpose for owning a gun is to hunt, or to scare away a burglar, a hunting rifle should be sufficient.

I’ve spent time in the military, and I’m familiar with the weapons Rachel describes as “assault” weapons. We actually had to carry them everywhere while we were in military training- even to the point where you had to sleep with your weapon in your bunk next to you. It wasn’t pleasant, and I have no desire to have a weapon like that now. I agree that some weapons don’t need to be in private hands, and that high capacity magazines to increase the number of rounds in a weapon have no place on the street. Honestly, most hunters don’t truly need a semiautomatic.

While I do support restrictions on weapons, it does irk me a bit when people make statements that the writers of the constitution didn’t have knowledge of modern-day weapons, and therefore the modern weapons should be subject to different rules. What happens if we begin to apply that standard to other amendments… For instance, if someone says that the writers of the first amendment had no knowledge of electronic media, so the amendment doesn’t really apply, and the government should be able to censor websites (for instance, wikileaks)? Changes to the constitution have to be made by voting on amendments… Which, given rampant gun violence, is quite possible.

I think that’s a false analogy. Free speech is free speech regardless of whether it’s carried out on the Internet or verbally. It’s no more dangerous or threatening in either medium. But your “right” to bear arms fundamentally changes depending on whether that arm is a musket or it’s a semi-automatic rifle.

Hi Rachel. Thanks for this article, which I have a lot of feelings about. I haven’t actually put my thoughts together so bear with me.

While I don’t think vigilante justice is the answer (I mean really folks, nope. You’re probs not a hero, get that idea out of your head) I feel like a lot of this need for guns comes from a distrust of our social structure, one that’s failing and one that’s pushing certain pockets of this country that have some sort of distrust to change. So yeah, I think thats why a lot of conservatives are really clutching on to their guns, but I feel like we as a nation sincerely have to look at a shrinking social safety net and our culture of violence, thats only perpetuated from the top and then of course effects everyone.

I feel like a lot of this emphasis on violence comes from our government itself, and this excuse to be violent while claiming humanitarian causes is only mirrored in its people. Also, we have to question why a lot of the people who a: murder folks do so and b: why a lot of the people who do mass murders are men, especially young men. I think the machismo culture thats been created and perpetuated at every single stage of our lives-from the need to get gun like/violent toys as children (did you know they sell drone action figures in stores? Nooo kidding) to this push as they become young men to either serve their country by going to war or give accolades and honor to the people who have gone to war and occupied other territories in the name of freedom. And this constant fear of terrorists, no matter how fucking vague that word has actually become.

You put this in the context of an economic structure that is slowly taking away all hope for their people, that’s giving us fewer and fewer options so then we all question what chances we all have really when funding for education is shrinking, when unemployment goes up, when social servants are doing things like serving the upper class and enforcing shitty laws, providing more money for a growing industrial prison complex, then I mean, are we really so surprised that we’ve seen more violence?

I’m not excusing anyone from going out and performing this massacre. We just really have to look at why we, as the country that is supposedly supposed to be the most advance, are having these issues. It’s not a coincidence, it never was.

Anyways, I fel like this article was really well written, you rock. Love you, ok bye.

Reading the comments of gun advocates on this thread I am reminded of a quote from John Maynard Keynes: “When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, sir?”

So many assertions, so little evidence, and quite a lot of evidence to the contrary.

In Australia, when the Government reduced the number of guns in circulation by around one fifth, the gun-related homicide rate decreased by 59%, the gun-related suicide rate decreased by 22%, there was no corresponding increase in other homicides nor was there an increase in home invasions. Since the massacre in 1996, we have had no more mass shootings.

You can spout whatever rhetoric you want about armed civilians being bastions of liberty and peace and unicorns. I’ll stick with the society with the vastly lower homicide rate. Shame about those unicorns, though.

Complete agreement, Riese said in the previous articles comments she ‘couldn’t imagine not living with fear of gun violence’ or something close, i really really can’t imagine living with the fear of it, it just seems ridiculous…

In regards to the main article ‘mass shootings are rare events’ Does an average of 2 a year really count as ‘very rare’?

One important bit to note: the idea that more people carrying guns = more people safer from gun attacks is not automatically true. While there have been instances where people with guns have stopped other people with guns, as cited above, there have also been tons of instances where people with guns have NOT stopped other people with guns. Nancy Lanza owned plenty, and it didn’t do her much good. And that’s not because she did anything wrong in the moment- it’s because it’s pretty hard (read: impossible- see the mythbusters episode) to dodge a bullet. Adam Lanza killed 20 children and 6 adults in 10 minutes. That’s including the time it took to walk between rooms. That number doesn’t give me much hope for increased safety via more gun carriers.

Furthermore, take these two studies: http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/09/090930121512.htm (results finding that people owning guns are 4.5 times more likely to be shot during an assault) and http://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/johns-hopkins-center-for-gun-policy-and-research/publications/WhitePaper102512_CGPR.pdf (if you like really long reads, finding, among other things, that restricting high risk individuals from owning guns is helpful)

I think this is probably the best article I’ve read about gun culture in the wake of this shooting:

http://opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/12/16/the-freedom-of-an-armed-society/

because it talks about just how fundamentally fucked-up the notion is that we fix gun violence by arming more people, and the notion of “an armed society is a polite society.” Yeah, TOO polite. Free speech partly means not having to always be polite, and not having to walk on tip-toe around everyone with what you say – which is what we’d have to do in a society where everyone was armed.

I also like the point about stigmatizing the mentally-ill, because even if there were a stronger link between mental illness and murder, I think the real problem are largely the people who are not getting diagnoses and treatment. Going to a psychiatrist and getting on medication – if you’re an adult – requires some acknowledgement that something is wrong, most of the time. To me, the real problem are the people who have serious mental health issues but insist that they couldn’t be anything but normal.

I’m also getting really sick of seeing discussions online where people pat themselves on the back for being neurotypical, from people who buy hook, line and sinker into baseless conspiracy theories about vaccines causing autism or whatever. I think there’s a much greater threat from people with no diagnosable mental illness who are under the “influence” of political or religious extremism (as a lot of conspiracy-theory groups are) – or, as Rachel pointed out in this article, drugs – than there are from the mentally ill. “Under the Banner of Heaven” from one of the recent Things I Read That I Love posts is a good examination of this.

Rose, you always leave super interesting comments. I loved that NY Times article – especially the reference to Arendt: “Violence — and the threat of it — is a pre-political manner of communication and control, characteristic of undemocratic organizations and hierarchical relationships. ”

Very interesting.

very nice blog you have here would like to see more posts though.