If you know me personally, even a little bit, it’s no surprise that my “guilty pleasure” is following stay-at-home moms and homemakers and other women who are forging new relationships with things considered “traditionally feminine.” I’m Jewish, and so lots of those women are Jewish, many of whom see following the Jewish laws around family purity, or niddah, as important to the way they structure their lives. The laws of niddah center around behavior determined by whether one is in a state of ritual purity or impurity. TL;DR, misogyny has transformed these states of being that determine how one acts into moral designations that have made folks who have periods (and historically, specifically women who have periods), feel as if they are lesser because they bleed.

What the Instagram ladies are really into debunking right now (and what I’m going to connect to housekeeping and domesticity, I promise), is this idea that a state of being is or should be a moral designation. This was a powerful moment of unraveling for me as someone who often finds that I determine my worth by how clean and tidy my home is, as if a mess is an indication that I am somehow a bad person. What my hobbyist’s interest in the laws of niddah has opened up for me is the danger in morally assigning value to a physical state.

It is so easy for me, especially as a cat owner and roommate (after living alone for five years), to feel like my mess is an indication that I’m a shitty person who doesn’t care about my housemate having a positive living experience. When someone tells me that they can smell my cat’s litter the first thing my brain goes to is thinking that I’m a terrible person. This not only isn’t true, it often stops me from being able to find a solution; instead, feeling overwhelmed by shame.

And, of course, we know the reason behind this is misogyny! Alongside misogyny comes the binarisation of work, and when you’re not good at domestic life and you’re a woman (or someone who was raised to see themselves that way, or you have a complicated relationship with being a not-a-woman-but-of-women’s-experience), then you become a bad woman, a bad person. The state of our work, of the things we do, has become attached to our worth in a way that I don’t think it has for cis men. Let’s make housekeeping one of the places we begin to intentionally unstitch these things from one another.

As we queer homemakers deconstruct our relationship with domesticity, part of it is a reminder that it is not a way to morally designate ourselves as better than anyone we know, it’s a way to make our homes our own. It’s worldmaking. It’s creating little utopias for us to practice in while we continue the work of building a better world. So we shouldn’t see the state of our homes — whether they’re pristine or filthy — as indications of who we are as people. Some of the best people I know have roaches (I’m not eating over their house but that doesn’t make them bad people).

I wish this had more practical tips in it, more ways for you to clean hard things that sometimes lead to you feeling like a shitty person, but that’s the thing. You’re not shitty. Even if your roommate passively-aggressively vacuums at 9:43 pm in front of your door. Mess happens. Disorder happens. And it requires us to behave differently — not having folks over if/when you just need to wallow in piles of dirty clothes — but it doesn’t mean we are bad people.

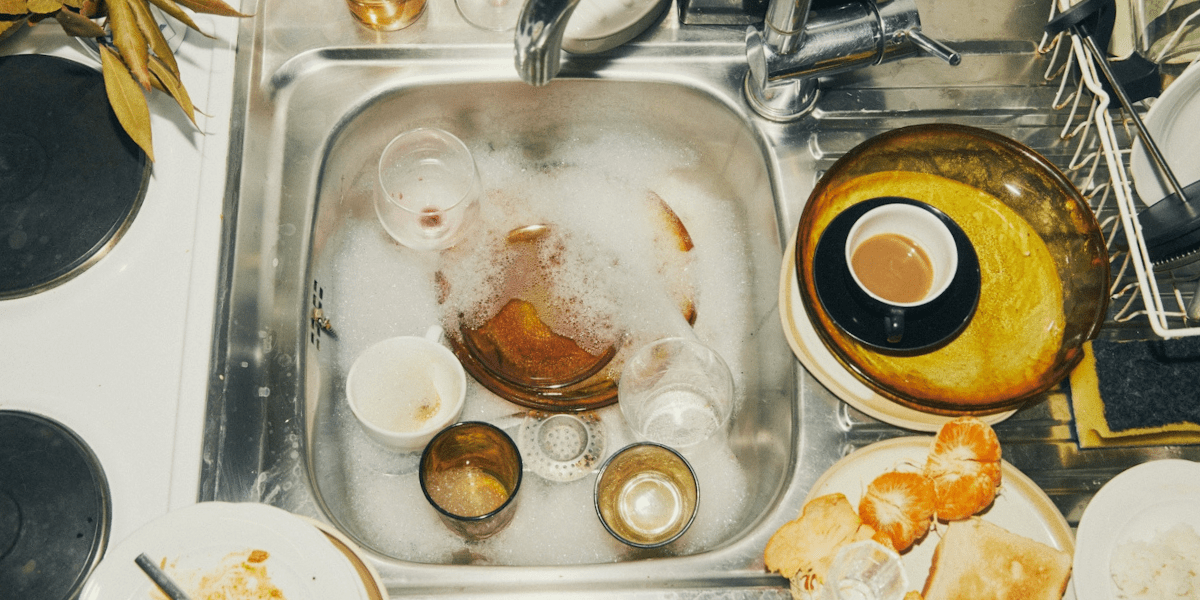

And the thing about it is that we never stay in one state of being forever — just think about the dishes. As soon as they’re all clean, you use one, and then suddenly your sink is full. I want you to be the best housekeeper you can be. And if and when you can’t, I want you to know more than anything, that you’re still a good person.

Notes for a Queer Homemaker is a regular column that publishes on the fourth Friday of every month!

Comments

Oh wow, did I need to read this today. Thank you.

This is such a loving, generous article that I got a little teary reading it. Especially since I looked around our bathroom this morning and knew that a) it’s looking pretty gross and b) I don’t have the energy to clean it. So now I’ll add c) and that’s OK.

this was lovely and important! thanks, ari.

I immediately felt seen.

Thank you for this. Shabbat shalom!

I didn’t know I needed to read this today, but I did!

As I am stuck at home recovering from Covid, I found myself thinking that I might as well be cleaning. Should be cleaning. Thank you for making me rethink that!!

👏👏👏👏👏

Roaches would be a non-starter!

I love this so much! I am also so curious about who you are following…

❤️thank you this was a needed read.

Thank you for this- count me in with those who needed to hear it.

I needed this too <3

Also: "Mess happens. Disorder happens." Sometimes I forget, but entropy is the law of the universe. It takes way more energy to fight it than to let it happen. There's nothing wrong with conserving our energy sometimes.

❤

Holy smokes Ari. Add me to the list of people who didn’t know they needed to read this! You just connected some dots I didn’t even realize were on the same page as each other damn

Yesss ❤️ thank you

“When someone tells me that they can smell my cat’s litter the first thing my brain goes to is thinking that I’m a terrible person. This not only isn’t true, it often stops me from being able to find a solution; instead, feeling overwhelmed by shame.” – I felt this so deeply. Thanks for lifting some of that shame for so many folks today.

But HOW do I keep it clean? It seems no matter what I do it immediately becomes messy again. It makes me feel like no one is going to want to live with me because I’m disorganized. I even make a rule not to have roommates because of it. I just don’t know how to keep everything in order. Would love any advice.

Personally, I found this video really helpful, ymmv

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0mCr5tqtiMg

Wow I did not know it was going to make a huge embed from just the simple link. Sorry and also is there any way to fix? O.O

I’m a fellow messy person! I’ve been living with my partner for a couple of years now, and the state of the house has been an ongoing challenge for us. She’s more organized than I am. It’s taken both of us seeking a common ground. I’m always trying to be tidier, and she tries to be more understanding. She can see that I’m not intentionally messy.

Steps that I’ve taken:

– if I use something (toothpaste, floss, comb, etc) I put it away immediately

– set a timer while cleaning

– clean certain rooms on specific days (I’m not great at this)

– keep my mess to one area behind a closed door

– get drawer organizers

-make cleaning fun with new products, tools, techniques so it feels less like a chore

Hi Hannah!

I wrote a comment that was partly for you about the Executive Functions of the prefrontal cortex of the brain. I think this info will be very validating and helpful. We all have strengths and weaknesses in our functioning. I am tidy and clean but chill about it too however I am weak in planning, time management, remembering to do tasks like call the doctor or follow up on a task. Look it up and I think it will be helpful.

This resonated so much with me! Thank you!

Thank you for this article! It is important to say these things out loud to start separating habits or circumstances from self-worth.

Hannah, I want to say that the Executive Functions of the prefrontal cortex of the brain have different domains and everyone develops them to varying degrees. Look it up and it might help to know that you might just have less development of functions like planning and organization. Some ppl find it hard to have habits that others find so easy. Families of origin teach different habits. I was raised by a neat freak, so I have good tidying and cleaning habits. But my husbian had parents who cleaned up after him, so his habits are different.

I have a secret sponge that he doesn’t know about so I don’t have to use the nasty sponge he leaves sopping wet in the sink. We as humans can find ways to cohabitate with less angst.

Good luck with your quest to develop the habits you want. I suggest reading about Executive Functions as a starting point.