Along with discrimination, violence, homelessness, social stigma, mental illness, poverty, and many more, one of the most pressing issues for the queer community is the lack of research on us — because that’s one of the only things that can prove the former problems exist, and maybe help us call for a solution to them. This week, a really significant and fascinating new study changed not only the information we have about queer people, but it may change what we know about research on queer people as a whole.

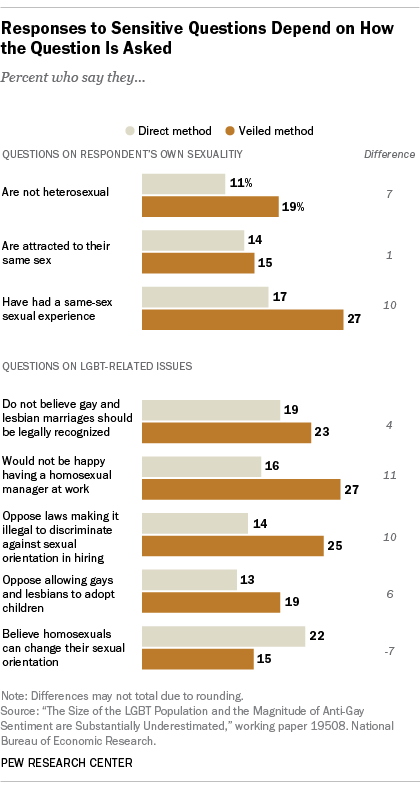

In a study published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, researchers found a new way of gathering information from participants that’s even more anonymous than previous anonymous survey techniques have been — as the Pew Research Center says, this technique “makes it virtually impossible to connect individual respondents with their answers to sensitive questions.” (The PRC explains in greater detail exactly how this works.) When the participants in the survey felt more assured that their answers couldn’t be associated with them, they answered in significantly different ways when faced with questions that dealt with LGBT identity. Specifically, participants were more likely to indicate that they were not heterosexual with this research method than with any other — and participants were also more likely to disclose anti-gay sentiments.

It’s important to note that although most of the public discussion about this study has centered around the fact that there may be more LGBT people in America than previously thought, that isn’t the main takeaway of this study — or at least, not one that the researchers themselves are willing to confirm. Because the 2500 participants of the study weren’t gathered in such a way as to constitute a random sample of the adult population (they were found through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk program), “the researchers do not attempt to estimate the actual size of the country’s gay and lesbian population.” Basically, although 10% more people said they had had a same-sex sexual experience than they did when they weren’t as anonymous, that doesn’t mean we can assume that 10% more of the population has had same-sex experiences as we had previously thought.

We especially shouldn’t draw broad conclusions because frankly, this data doesn’t support them. In research about the queer community, misunderstandings about terminology and identity mean that there’s a lot of tendency towards inaccuracy, and we need to be careful about how data is interpreted. There are already plenty of difficulties and confusions in reporting statistics about queer people, like the fact that according to the 2011 Bisexual Invisibility report, data about bisexuals is often lumped under data for gays and lesbians, making the conclusions about both less accurate. For instance, there was a much greater uptick in the number of people who said they were attracted to the same sex than people who said they weren’t heterosexual. What does that mean? Are there people reporting that they’re not heterosexual but aren’t attracted to the same sex as them? We don’t really know, which is why we should be careful about making sweeping statements about the queer population based on these numbers.

The conclusion we can draw is that there’s still significant enough social stigma around the idea of reporting same-sex attraction that some people are avoiding disclosing it out of fear or shame — even in situations where repercussions are highly unlikely, like a research study. This does mean that, while we can’t guess at a number, it’s probably higher than we thought it was. What’s potentially even more interesting is that there appears to also be at least some stigma or shame associated with being anti-gay, so much so that people were significantly more likely to disclose that they oppose equality in the workplace or would be upset with having a gay boss. Although it’s been clear for some time now that the social cachet in supporting gay rights is increasing and is decreasing when it comes to denying them, this is some hard evidence that illustrates how it’s playing out. The most puzzling part of the survey results is the fact that people are less likely, not more, to say that they believe sexual orientation is changeable when they’re extra-anonymous. This bucks the across-the-board anti-LGBT statements in the rest of the results, and according to the researchers, “indicates that participants saw it more socially desirable to report that sexual orientation is changeable, which goes in the opposite direction of a general ‘pro-LGBT’ norm.”

This study is far from final or comprehensive — if anything, it’s giving us a peek at the tip of the iceberg of how much we don’t know about our own community (and the people who oppose us). The researchers say that the group they worked with actually probably skews younger and more liberal than the average population, such that “some of the groups under-represented in their study are probably more likely to hold anti-gay views or be less willing to say that they are not heterosexual,” meaning that these results might have been even more extreme with a random sampling. (Although, again, we shouldn’t generalize!) We don’t have enough information to take away very much specific insight about our community, but this is a big heads up that layers of social stigma have made the little we thought we knew harder to rely on, and a heads up that we need much more research in this vein.

Comments

This is really interesting. Thanks for passing it along!

“The most puzzling part of the survey results is the fact that people are less likely, not more, to say that they believe sexual orientation is changeable when they’re extra-anonymous.”

This actually makes sense to me. The justifications against LGBT rights are just that: justifications. And, in private, people are more willing to admit that.

You see that now, with evangelical Christians ignoring the dozens of Biblical references to eunuchs to craft an anti-trans theology.

I had the same reaction when I saw that statistic reported. I think it’s also representative of how bigotry operates in the first place: the goal in the mind of the bigot isn’t necessarily to develop any logically consistent narrative of who the “other” is (they don’t actually care), it is only to make such bigotry appear socially palatable enough to bring it up to a stranger or in the public sphere and see if they can get away with it. And many bigots are perfectly willing to contradict themselves in designing that narrative of the “other” if it fits their purpose at a given moment.

This is really cool info!

I can’t believe they used MTurk for this. Just…what?

really makes me regret not sticking with being an mturker

I’m pretty confused as to how they could correlate answers for sensitive questions when the ‘secret survey’ form doesn’t actually account for which answers were selected – just the sum of answers per page.

Passing stats nerd here! I haven’t read the detail of their methodology (don’t have access to the paper), but I can take an educated guess.

The trick is to give different combinations of questions to different respondents, then compare results to figure out how common each individual answer is. As a simplified example, suppose we have three questions A, B, and C. Let ‘a’ stand for the proportion of people who would answer yes to question A (assuming they felt sufficiently anonymous), ‘b’ for question B, and ‘c’ for question C – these are the things we want to estimate.

We recruit a big bunch of people and split them up into three groups. Group 1 gets questions A+B (and only reports their total number of ‘yes’ answers), Group 2 gets B+C, Group 3 gets C+A.

Say we find that Group 1 reports an average of 0.4 “yes” answers, Group 2 reports an average of 0.5, and Group 3 reports an average of 0.9. If we assume the sample size is large enough to ignore sampling error, this tells us:

a+b=0.8

b+c=0.5

c+a=0.9

Add these all together, and you get: 2a+2b+2c=2.2. Divide by two, and you have a+b+c=1.1.

Since we know b+c=0.5, we can subtract this from the total: a=1.1-0.5=0.6. Similarly we can work out that b=0.2 and c=0.3.

In practice you would want to give people more than two questions, because if they answer 0 or 2 then obviously you could figure out all their answers. But the basic idea is the same.

(apologies for rabbiting on)

edit: now I follow the Pew Research Centre link, that one gives more detail about the method. It’s pretty similar to what I said above, except that you’re basically comparing people who reported (a+b) to people who reported (a+b+c).

Ahhh, that’s fascinating! I never thought of that, but that makes sense. So each answer is given a specific weight/value?

After reading Pew’s summary, it’s a bit simpler than I’d thought. As an example, one of the statements is “I am not heterosexual”. That gets presented to respondents in one of two different ways:

– Group A gets four innocuous questions & is asked to report the total from those four, then gets asked the “I am not heterosexual” question separately. (So they have to give a direct answer to that one.)

– Group B gets all five questions together, and has to report the total.

So from Group A you can figure out the average number of “yes” answers for questions (1+2+3+4) combined, and from B you can figure out the average for (1+2+3+4+5) combined, and taking the difference of those two gives the average for question 5 (“I am not heterosexual”) when asked through the “veiled” method. Group A shows you what the average for question 5 is when asked as a separate question, so by comparing the two you can figure out how much difference the method makes to your answers. (Though you have to figure out what the margin of error is – I won’t go into that here.)

I want to emphasise that this one is primarily about how the question is presented, NOT what the question actually is. We could question whether “I am not heterosexual, agree/disagree” is a good choice of words – but both groups got asked the same questions in the same words, the only thing that differs is whether they had to answer it as a separate question or more ‘deniably’ as part of a total.

The fact that they got similar results with other sensitive questions can be taken to suggest that the standard method of questioning probably leads to significant underreporting on this sort of thing.

I saw an interesting piece of work from South Africa that worked on a similar idea of letting people answer deniably. (I think it’s called “randomised response method”.) The researchers wanted to know how many farmers were shooting leopards, which is illegal but widespread. So they got farmers to roll a 6-sided die and told them: roll this, out of our sight. If you roll a 1 say “no”, if you roll a 6 say “yes”, if you roll any other number tell us whether you’ve shot a leopard.

If you survey 600 farmers, you can assume that approximately 100 will answer “yes” because they rolled a 6, and 100 “no” because they rolled a 1; by subtracting 100 “no” and 100 “yes” responses from the total, and looking at what remains, you can estimate the proportion of farmers who answered “yes” to shooting a leopard. Which turns out to be a lot higher under this method than when you ask them the question straight out, even with assurances that the answer can’t be used against them.

This side of things isn’t my area of stats, BTW – I’m a mathematical statistician, not a psychologist, and I don’t design the questions myself. But I find it fascinating all the same, and it’s terribly important – if the questions aren’t asked correctly, then the data I have to work with is going to be rubbish.

Interesting read. I find it odd that having a homosexual manager is apparently A Big Concern – I wouldn’t have expected people to be unhappier with queer supervisors than with same-sex adoption.

Having a queer boss gives an LGBT person power directly over them, as opposed to power generally over a hypothetical non-them child

“according to the 2011 Bisexual Invisibility report, data about bisexuals is often lumped under data for gays and lesbians, making the conclusions about both less accurate.”

And if bisexuals are often lumped under data for gays and lesbians, it makes me wonder why the trans community is even mentioned in such surveys? If anything, saying ‘LGBT’ just minimizes the most ignored subgroupings and implies that, because a gay cis man or cis lesbian is reacted to a certain way, it therefore also applied to trans people… which is absurd and completely makes trans (or bi) issues invisible. I’ve previously mentioned my feelings about the value of the Pew survey’s “claimed accuracy/conclusions” about the trans community, which are absurd and I don’t see this as being any better. So much of it has to do with the very specific questions asked, their wording (and moreover, the assumptions contained in those questions) and not how supposedly anonymous the methodology is.

This is quite an interesting perspective.

“Are there people reporting that they’re not heterosexual but aren’t attracted to the same sex as them?”

I wouldn’t suggest this is the ONLY reason why some people probably reported that exact combination, but… for the sake of clarity and stuff, it seems like it would have been smart of the survey-makers to account for asexual respondents when they were deciding what questions to ask about sexual orientation.

Because…that omission ultimately could only serve to make the data set less intelligible.