Welcome to the twenty-first installment of More Than Words, where I take queer words of all sorts and smash them apart and see what makes them tick. Every week I’ll be dissecting a different word, trying to figure out where it came from, how it has evolved, where it might be going, and what it all means. It’s like reading the dictionary through a prism. Feel free to send word suggestions to cara@autostraddle.com.

Header by Rory Midhani

So many people don’t know what “feminist” means. Really, so many. Taylor Swift (“I don’t really think about things as guys versus girls.”). PJ Harvey (“I don’t ever think about feminism. It just seems a waste of time”). Marisa Mayer, CEO of Yahoo (“I think that I certainly believe in equal rights… but I don’t have the militant drive and the chip on the shoulder”). Bryan Goldberg, CEO of Bustle (“you’re damn right it’s a feminist publication!”). Many of my male coworkers (“but I don’t want women to have more power than men…”).

It’s enough to make a self-identified feminist doubt herself. Do I really know what the word means? I’d always thought so, but the prescriptivist and the descriptivist in me began warring, and I had on my hands a crisis of definition. So I did what I always do when I have trouble understanding a word — I tried to figure out where it comes from. This was a particularly nice journey because I got to go to France in my head. Come along with me and maybe we can work it out together.

The English word “feminism” grew directly out of the French féminisme, via an ocean-jumping process we will get to in a few minutes (patience, grasshopper). Feminisme has its own history, one that also sheds light on related standbys such as “feminine” and “female” as well as more recent coinages like “femme.” If you trace back the Latin root these words all have in common — “*fe” — as far as possible, you get the Proto-Indo-European root “*dhe,” which means “to suckle [something]” (e.g. a baby) or “to produce,” proving that the people in charge have been primarily equating ladies with boobs since literally the beginning of language.

This same “fe” construction developed into a strange and varied menagerie of words, including “fetus,” “felicitations,” “fecund,” and, yes, “fellatio” (woooo). The route it took to get to feminisme was a fairly straightforward one, from the Latin femina (“woman”) through femininus (“feminine;” originally a strictly grammatical term but later expanded to refer to other things), and finally Old French femenin (“having female qualities”). Meanwhile, the suffixes “ist” (English) and “iste” (French) both come from the Latin “ista,” meaning “adhering to a certain set of principles.” By the time French féministes needed a word for what they were doing, both puzzle pieces were established and close at hand.

Who exactly stuck them together, though, and when exactly they did it, are matters of debate. Everyone agrees that it was some time in the mid to late 19th century, when France was going through a time of political upheaval that also gave rise to fellow principle-sets socialisme and individualisme. Many give the credit for féminisme to philosopher Charles Fourier, probably because he really liked making up words and was certainly some kind of a feminist, especially for his time. Fourier is most famous for his ideas about “attractive work” — he wrote extensively about his vision for an ideal, future society in which everyone is assigned jobs based on their interests and desires and lives in giant hotels arranged by wealth level (richest on top). He believed that such a society could only function if women were allowed to participate equally, saying that “the best nations have always been those which concede the greatest amount of liberty to women.” His related conviction that the ocean will soon be made of lemonade — based on the fact that God wouldn’t have given children sweet tooths if he wasn’t going to pony up eventually — is less famous, but nearly as awesome.

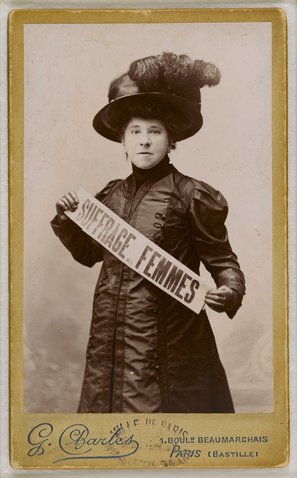

However, it seems Fourier didn’t coin the term — extensive research by Stanford historian Karen Offen shows no evidence of the word in his writings, and chasing the rumor proved “a frustrating exercise in circular citation.” Other theories give the credit to Hubertine Auclert, who lived and worked in the mid 19th-century and was born shortly after Fourier died. Auclert was a suffragist, an editor (of founding feminist journal La Citoyenne, or “The Female Citizen”), an organizer, and a total badass. She staged a tax revolt to protest women’s lack of representation in government (so much cooler than license plates), invented prenups, and illegally ran for office on many occasions. As if that weren’t enough, some people think she invented the word feminism, in 1882, to describe the goals of La Citoyenne, herself, and her compatriots.

I couldn’t find a primary source for this claim, or any kind of general agreement about it. What people do seem to agree on is who brought the word across the ocean to America and translated it into English. The culprit? Dr. Madeleine Pelletier. Pelletier’s work as the first female French psychiatrist and physician influenced her development and practice of a “radically individualistic feminism,” focused not on advancing the causes of women as a distinct and cohesive group, but rather on obtaining equal rights and opportunities for individuals, regardless of gender. As Claudine Mitchell explains, Pelletier:

“broke with nineteenth-century feminism to develop a cultural theory of sexual difference. To articulate the case for sexual equality, nineteenth-century feminists had extolled the social value of women’s traditional roles and celebrated feminine virtues over masculine vices. This was the wrong track, Pelletier thought, since it confined women to their traditional roles by rooting femininity in biology. If, on the contrary, it could be proved that femininity and masculinity were the products of culture, than feminism could make advances by attacking cultural phenomena.”

Basically, Pelletier was throwing around ideas about “psychological gender” as a construct of society and upbringing a good 80 years before Butler. She studied sexuality scientifically despite an immense taboo, dressed in men’s clothes, had an alternative lifestyle haircut, and pretty much invented the phrase “I’ll show you mine…” and immediately used it to fuck with the social order (“I will show off mine [breasts] when men adopt a special sort of trouser to show off their…”). She also dealt with the kind of gendered linguistic double-standards we talked about last week (an honest man tells the truth; an honest woman is a virgin), performed illegal abortions, and snuck into Communist Russia and lived to write a book about it. On top of all that, she managed to publish a paper, “Le féminisme et la famille,” that made its way to America, translated as “Feminism and the Family,” in the early 1900s. And the rest is history (well, this was all history. But the rest is future history, because we’ll cover it next time).

Since the beginning, “feminism” has meant different things to different people, from Fourier’s utopia-based inclusiveness, to Auclert’s desire for a matriarchy, to Pelletier’s individualistic view. Auclert and Pelleteir broke stuff side by side in the name of suffrage (Pelletier threw a rock through a window; Auclert smashed a ballot box), but argued academically about whether the nuclear family should be exalted, as the best setting in which to practice equality (Auclert) or destroyed, as the number one institution preventing it (Pelletier). The definition is, and has always been, simple — feminism strives for equality for women. It’s the words within the definition (what kind of equality? who counts as a woman? and how best to strive?) that are, and have always been, hard to pin down.

Comments

i would totally make hubertine auclert AND madeleine pelletier waffles.

I see what you did there. ;)

also what if god does actually pony up eventually and one day the ocean is made of lemonade?

…HOW DOES SOMEONE’S BRAIN COME UP WITH THAT IDEA?! truly, how do human brains work. who makes up these stories? i don’t even know what to say.

If the ocean turns to lemonade I think the only reasonable response would be to add vodka to it.

Beyonce identifies as a feminist, although somewhat tentatively: “[the word] can be extreme…I guess I am a modern-day feminist. I believe in equality.”

Having said that, I don’t know that the issue is so frequently that people don’t know the definition. Feminism isn’t just a definition in the dictionary, it’s also a larger phenomenon, and a large and diverse movement with over a century of history and lots of theories and power politics. People should be allowed to take the larger phenomenon into account when they’re being asked to take on a label as part of their identity.

I understand how problematic the term “feminist” is and it pretty much never consistently considers race,sexual orientation, class, etc. It does feel like only something a middle class white woman can call herself. I am sexually miscellaneous, and black but I still refer to myself as feminist because at it’s core I feel like it represents equality for everyone. I know that men and women are different, that is the common argument I get from people to discredit feminism but the main problem is that men’s skills were considered more valuable then women’s and allowed them to expand and progress, and control the overall state of things. I think our differences as people should be supported and celebrated. Being a feminist means making decisions based on the fact that regardless of our culture I’m going to do what is right for ME.

Love this… the article and your reply. It touches on so much… It seems so crazy to me that many black women think feminism is for “middle class white” women.. I mean, some of the greatest feminist activists/writers/icons were WOC: BELL HOOKS anyone?! I mean… middle class white women (and blue collar white women such as myself) would not be where we are if it weren’t for black feminists.

One thing that could be touched on is why feminism has become the new “f” word… Thank Reagan-era media coverage for that hot mess. But I think, when confronted with a closeted or confused feminist (lol), it’s best just to quote Caitlin Moran:

“But, of course, you might be asking yourself, ‘Am I a feminist? I might not be. I don’t know! I still don’t know what it is! I’m too knackered and confused to work it out. That curtain pole really still isn’t up! I don’t have time to work out if I am a women’s libber! There seems to be a lot to it. WHAT DOES IT MEAN?’

I understand.

So here is the quick way of working out if you’re a feminist. Put your hand in your pants.

a) Do you have a vagina? and

b) Do you want to be in charge of it?

If you said ‘yes’ to both, then congratulations! You’re a feminist.”

You don’t have to have a vagina to be a feminist. And I agree with the commenter further up, that imposing labels of any kind on people isn’t cool. There have been a LOT of different iterations of “feminism” over the last few decades, and some of them had super fucked-up ideas about what that word should mean – ideas involving things like the exclusion of WOC and trans women from feminist movements.

You are a gross transmisogynist, quoting another gross transmisogynist.

Bigots like you are the reason feminist has so much baggage.

oh Caitlin, Caitlin….purely to show that i’m not twisting the letter of this silliness against the spirit of it i will adopt a fairly obvious third criterion, a wholehearted commitment to equality. and i match across all three.

but guess what – not only you’re wrong but you couldn’t be more wrong. In fact you couldn’t be more wrong even in a fictional scenario wholly constructed around you being wrong and taking place in a hypothetical possible world where the only things in existence are you and your wrongness.

why?

1) you forgot the hidden criterion of groupthink capability and ability to feel its momentum which i do not posess.

2) you forgot the tradition – and reverence for heroes/saints – which i do not have in the slightest.

3) no system of faith and belief drives my loved one to hard reset and continues to be an option in the same time. the number of late loved ones greater than 1 adds to this formula as the power it is being raised to.

So, you decided that the best way to convince a black woman to just be more like bell hooks was to quote Caitlin Moran, who really epitomizes racist feminism?

“It seems so crazy to me that many black women think feminism is for “middle class white” women.. I mean, some of the greatest feminist activists/writers/icons were WOC: [bell hooks] anyone?! I mean… middle class white women (and blue collar white women such as myself) would not be where we are if it weren’t for black feminists.”

Sounds a hell of a lot like you’re *blaming* Black women for not wanting to be part of a movement that we as white women have invaded and co-opted; that we’ve frequently made a profoundly racist space that, yes, only serves the needs of us as white women and actively excludes and marginalizes and silences women of color.

That’s fucking awful, and all too common in white activist circles that prefer to try to sweep racism under the rug and insist that people of color are just too (insert dehumanizing racist stereotype here) to join.

haha i read these every week and am always thinking the same thing afterwards, that being: ******you’re smart*******

“more than words” is the absolute best thing on autostraddle, thank you very muchos.

sleeper hit of the summer

I love where all of your links take me! I could get lost in these sites for hours <3

Love the article; can’t wait for part II (we need visible feminist role models — Michelle Obama is great, but I’m gonna need more revolution than a white house organic garden when my pay is automatically a fifth less because X chromosome.) The photos are so great! My jaw dropped seeing Pelletier in a suit — that’s an example of the level of intensity I think the movement really needs; women and men who really commit to living their lives according to their beliefs. There should be a NetFlix drama about radical feminists, I would watch the hell out of that.

Pussy Riot gives me hope.

.. my next halloween costume!

Oh wow least surprising comment. Did y’all totally-not-racist-transmisogynists come from the same terf blog?

my prediction: february 2017, the old radical mobama comes back.

TV series? There is. It is called Sarah Connor Chronicles. It’s about a cute, awesome, resourceful woman trying to survive in a wrecked world that’s resulted from people’s own radical gut feelings, desire for a bitesized black-and-white picture and kneejerk hostility – all of which is really not Sarah’s fault. And on the anti side of the trenches – it had Shirley Manson playing on Team Skynet – i adore her, it is an honour.

If all other things were equal and you had a Y chromosome instead, you would be payed even less. Trans women get docked for being trans and being women.

“…when my pay is automatically a fifth less because X chromosome.”

~Yeah it’s super convenient that people check my chromosomes and then decide not to treat me with misogyny. Because when trans women are outed as trans, we totally get accepted and treated better, rather than continuing to be subjected to misogyny and having even more discrimination heaped on top.~

Here in the real world, you can piss off.

And it’s super telling that you lambast Michelle Obama as not a good role model but pussy riot ‘gives you hope.’ ~I’m sure that has totally nothing to do with race, nope.~

I had a coworker tell me just the other day that she’s not a feminist. She hates sexism, (which there is a bit of at our job, from one of the older female managers), but she gets along better with men so she’s not a feminist.

I read some of that Charles Fourier page and sort of he was right: he said sugar and things made with sugar would be cheaper than bread because making bread was less attractive, and sugary processed snacks and all that jazz are definitely cheaper, just not because making bread is unattractive.

I only came here so I can use the funny keys on my French keyboard.

Féminisme. Féminisme.

Look at those too! èÈùÙêÊàÀ

Also Madeleine Pelletier… not sure if completely amazed or sexually aroused.