Welcome to the fifteenth installment of More Than Words, where I take queer words of all sorts and smash them apart and see what makes them tick. Every week I’ll be dissecting a different word, trying to figure out where it came from, how it has evolved, where it might be going, and what it all means. It’s like reading the dictionary through a prism. Feel free to send word suggestions to cara@autostraddle.com.

Header by Rory Midhani

There’s a song I love by The Replacements. It starts with this shambling, vaguely backwards-sounding piano, accented by faint whistling. Plaintive and sunny at the same time. Then Paul Westerberg starts crooning:

“Here comes Dick, he’s wearin’ a skirt / Here comes Jane, you know she’s sportin’ a chain…”

Paul gets kind of choked up singing it, especially around the bridge. Sometimes Laura Jane Grace and Joan Jett cover it and it’s so perfect it’s rough to watch. It is, essentially, the children’s book some of us weirdos looked for in vain. “Now somethin’ meets boy, and somethin’ meets girl / they both look the same, they’re overjoyed in this world…”

“Androgynous” is simple word math. Andro is the possessive form of aner, Greek for “man,” itself from the PIE root *hner. Gyne is Greek for “woman,” from PIE *gwen, “honored woman” or “wife” (or “Stefani”). The suffix *ous is from the Latin *osus and means “full of.” So andro + gyn + ous = “full of man and woman.”

Straightforward, you would think! But like so many other words, this literal definition has been figuratively interpreted over and over again throughout history. Even today, it means different things to different people — a mere six weeks ago, a certain popular actress christened herself Zoe Saldana Androgynous when she maybe meant to say Zoe Saldana Bisexual. Even when people are more on the mark, a word (and an idea) as evocative as androgyny is bound to be co-opted for all sorts of purposes. Such as to describe the origin of the universe, or David Bowie, or your new sneakers, which are all probably the same thing anyway, right? Let’s go back in time and see if there’s anything people haven’t tried to make androgynous.

Like so many queer words, “androgynous” has ridden a sine wave of respectability. Its first major namedrop — by Aristophones, in the oft-cited “Origin of Love” passage from Plato’s Symposium — describes an early curve:

“In the first place, let me treat of the nature of man and what has happened to it… the sexes were not two as they are now, but originally three in number; there was man, woman, and the union of the two, of which the name survives but nothing else. Once it was a distinct kind, with a bodily shape and a name of its own, constituted by the union of the male and the female: but now only the word ‘androgynous’ is preserved, and that as a term of reproach.”

So even back in 380 B.C., some were looking back fondly at the days of respectable androgyny. Fast forward nearly two millennia, to when the word jumped into English, and you’ll find society was still on the fence. Was it a clinical term, an early equivalent of the modern “intersex” as lexicographer Richard Huloet’s 1552 dictionary would have it (“Androgine, which bene people of both kyndes, both man and woman”)? Was it obsolete by 1601, replaced by a term that has itself since fallen from favor (“Children of both sexes, whom wee call Hermophrodites… in old time they were knowne by the name of Androgyni”)? Was it another word for “an effeminate Fellow,” along with “scrat,” “dapper” and “Will Jill”? An astrological designation for planets that change temperature (“Androgynous as Mercury, which is reputed hot and dry when near the Sun, and cold and moist when near the moon”)? An insult disguised as a backhanded compliment (“What shall I say of these vile and stinking androgynes, that is to say, these men-women, with their curled locks, their crisped and frizzled hair?”)?

Except in botany — where it means “a flower with both a stamen and a pistil” and will never budge — “androgynous” has, appropriately, refused to pick a side (although some sociolinguists argue that it did at birth, maintaining that “the word ‘androgyny’ reveals the homosocial syntax of language, significantly, by placing the masculine part of the word before the feminine.”) It’s an equal-opportunity idea, used and abused by all kinds of people. Psychoanalysts (namely Freud, Jung, and everyone else who enjoyed distilling human development into so many clashing essences) made the coexistence of “male” and “female” energy central tenets of their theories. Feminists, particularly in the 1960s and 70s, strove to integrate it into the movement — whether on a social level, as explained by Carolyn G. Heilbrun in 1964, in Toward a Recognition of Androgyny:

“I believe that our future salvation lies in a movement away from sexual polarization and the prison of gender toward a world in which individual roles and the modes of personal behavior can be freely chosen… Androgyny seeks to liberate the individual from the confines of the appropriate.”

Or a philosophical one, as in June Thomas’s vision in her 1974 work Androgyny: The Opposites Within:

“The archetype of androgyny is the expression of the two-in-the-one, the paradox that an inner union requires an ongoing dynamic relationship of the opposites within…The androgyne accepts the inner opposites – not necessarily as points of internal conflict, but rather as parts that need each other to function, in order to maintain the whole.”

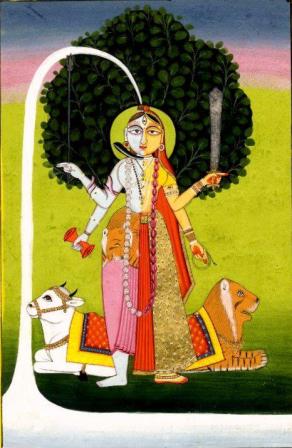

Religious scholars point out that androgyny has shown up in traditions throughout history and all over the world, often within creation stories (Adams’s rib; Ardhanarishvara; Plato again). Nikolai Berdyaev goes so far as to call the androgyny archetype “the great anthropological myth… original sin is connected in the first instance with division into sexes and the Fall of the androgyne, i.e. of man as a complete being.” Artists, particularly writers, have sometimes exalted androgyny as a kind of ultimate tool for empathy and balance — in her classic A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf picks up Samuel Coleridge’s idea that “a great mind is androgynous” and runs with it, speculating “that the androgynous mind is resonant and porous; that it transmits emotion without impediment; that it is naturally creative, incandescent and undivided.” Rainer Maria Rilke aimed at this too, saying “only the Hermaphrodite is whole.”

These days, you’re most likely to come across androgyny on runways and style blogs (androgyny has always been sexy, they say, but is “now an evolving, large-scale fashion trend”) or in scared op-eds and policy proposals from social conservatives who fear the dissolution of gender roles, the collapse of society, endless babies named Quinn and Dakota, and no one bringing them sandwiches.

All valid, all fascinating, and yet the patterns I see trouble me a little. In my research (especially when I found myself deep in academic or theoretical work), I noticed a preoccupation with the past — “androgyny is a thing from whence we came!” — and with the future — “androgyny is an ideal to which we’re headed!” Humans have a constant desire to wrap it all up neatly, even (especially) tricky, amorphous things like gender. We came from one all-encompassing thing, and we’re going towards another. Like most reductive social philosophies, this sounds nice at first blush (or scary, if you’re Representative Gingrey and you would rather we be two things, but two very settled and delineated things). But it ends up destructive — there’s no room for difference in a world where we’re all one. I’m glad there is a word for those of us who contain multitudes, but it’s strange to see it venerated by people with a single focus. As with a lot of things, I prefer the version in the rock song. No weirder than anything else, and no better either. Just another way to do you, to further be yourself. Tomorrow who’s gonna fuss?

Comments

“And they looooove each other sooooooooooo androgynous.”

I saw Joan Jett over July 4th weekend a few years ago and she sang this song, it was magical.

Love this column, I want to hug it with my legs in friendship.

I love these columns so much. They’re like checking in with my vocabulary and making sure we’re both still on the same page.

I’m a word nerd who has found her mother ship.

i am so glad that this column exists THANK YOU CARA (…who apparently has 100% overlap with all of the things i am interested in)

it’s true. that’s why you’re going to spare me in the cyborg apocolypse. (right?)

Love love love this!! Although it’s kinda making me feel uncool for not being or liking androgyny. Womp womp.

I’m not hugely into androgyny, but it can be very beautiful, especially if it expresses the person’s gender identity. There are a couple of important aspects to it I didn’t see here though. First, it isn’t always a compliment. It’s often a function of what’s sometimes called “gender attribute” (how other people assign to you and describe your gender). In other words, it’s not always an internal feeling about yourself but rather, other people’s projection onto you. For the first few years of my transition, the most supposedly positive thing I was ever told (apart from all the mean stuff) was how “androgynous” I was. I truly don’t think it was intended as any kind of insult (it was almost invariably women who told me this with a big smile) but it honestly felt no better than being told I ‘looked like a man.’ What I’m saying is, find out where someone is with their gender first, then bestow them with the “oh, you look so androgynous” “compliment.” It might be gratefully received and it might not.

Also, just because someone is androgynous doesn’t necessarily mean much about their gender identity. I’ve known straight, cis women who projected incredibly androgynous. There are some old people who are hugely androgynous but that’s through no effort of their own nor is it celebrated in the same way smooth, young androgyny is. In addition, all too often, androgyny is often culturally coded (especially in the rockstar realm) as white, thin and attractive. Thinness has nothing to do with androgyny yet if you look at who gets assigned that tag, it almost always has skinniness as a component.

I know this is definitely true in terms of Andrej Pejic. A lot of people have assumed that because of his presentation he must be trans or gay, but every time he’s been asked, he’s refuted it. Then again, he’s probably a bad example because he’s sort of the Lady Gaga of fashion, doing things for publicity, but it’s been interesting, people’s assumptions on him based on how he presents himself.

THIS. It took me forever to start iding as GQ/andro/whatever the fuck I want to be because my body is perceived as extremely feminine. So I spent years wearing dresses and halter tops and feeling like I was wearing a costume every day.

I love and own the term “androgynous” for myself. I think it really encapsulates the way I’m comfortable in a dress one day and slacks and a button-up the next.

I definitely hear what you’re saying regarding this idea that androgyny is the ideal, though! We’re all different and have different ways of expressing ourselves, and I think that deserves to be celebrated.

here’s another really good song feat. androgyny i wanted to put somewhere: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tQ63sYdWKmg

I just have to say that I love the song.