Welcome to the twenty-fifth installment of More Than Words, where I take queer words of all sorts and smash them apart and see what makes them tick. Every week I’ll be dissecting a different word, trying to figure out where it came from, how it has evolved, where it might be going, and what it all means. It’s like reading the dictionary through a prism. Feel free to send word suggestions to cara@autostraddle.com.

Header by Rory Midhani

This past week, the news was all over contemporary tech-addled linguistics, because trends.

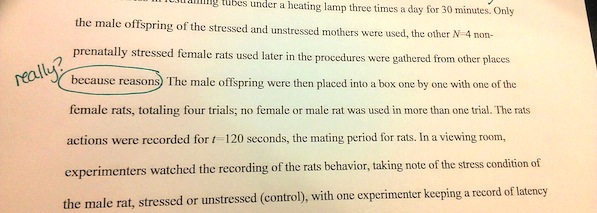

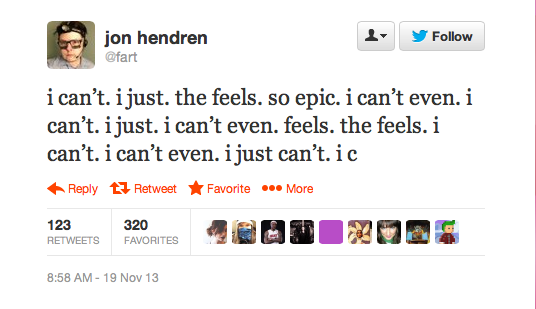

Everyone had an opinion on the Oxford Dictionary Online choosing “selfie” as their Word Of The Year (CNN: “The most esteemed guardian of the English language has bestowed a prestigious honor upon debatably the most embarrassing phenomenon of the digital age.” The New Yorker: “The modern-day selfie is… a novel iteration of an old form.” The Washington Post: “In this way, each selfie is one more breath blown into “the Oversoul,” which Emerson defined as the “common heart,” as individuals knit together in the ether.”). Ben Crair at The New Republic parsed out why the period has become the angriest punctuation mark (at least when texting. I’M not mad). The Atlantic‘s Megan Garber traced the evolution of the word “because” from a subordinating conjunction into an “exceptionally bloggy, aggressively casual, implicitly ironic, and… highly adaptable” preposition. Meanwhile, at The Toast, Tia Baheri talked about the beautiful complexity of “Tumblr-internet-speak” — how tweaks build on specific references build on general cultural knowledge until you get constructions like “I have lost all ability to can.”

While reading explanations of all these innovations that have slowly snuck into my typing vocabulary, I was struck by how many others I’m susceptible to that weren’t mentioned. Sure, I find myself just-cant-ing every once in a while. But most of the new things I’m really attached to aren’t just internet-speak — they’re QUEER internet-speak. According to Baheri, internet linguistics constitutes an unusual dialect because its users are “a group of people who have insider knowledge of the English language… placed in a new, unfamiliar, virtual space” where they have new communicative limitations (lack of tone, lack of context, time-jumps) AND new tools with which to fix them (images, commenting structures, hashtags, etc.). In that case, queer internet linguistics does the regular type one better — it happens when a group that’s already used to creating its own dialect is put in this unfamiliar, resource-heavy space. No wonder we’re ahead of the curve.

In the interest of giving this new sub-field the credit it deserves, I researched some current thinking on internet linguistics and applied it to some of my favorite queer-blog innovations. Read on for everything from asterisks to whiskey kittens.

Acronyms & Abbreviations

Long before trend piece writers took on complex grammatical constructions and the true meaning of cat pictures, they were all over the abbrev trend — a trend which, TBH, frightened many people. A quick scan of old articles reveals the following themes: Texting and IM-ing layabouts are mauling the language! “LOL” is showing up in English papers! “POS” = “Parent Over Shoulder” = teens are doing weird, secret sex roleplays whenever you’re not in the room! It was a bonafide wtch-hnt.

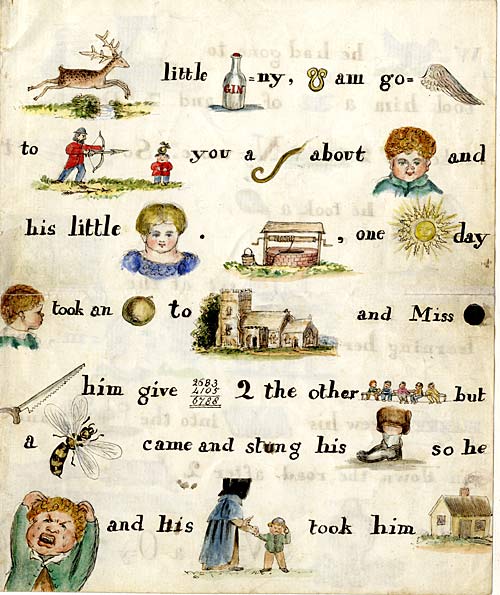

Five years ago, David Crystal, the OG of internet linguistics, wrote a book called Txting: The Gr8 Db8 that debunked a lot of the mistruths that had originally popped up: “As the research built up, it showed conclusively that none of these things were happening, that in the average text message only about 10 percent of the words are abbreviated, that most of the abbreviations in texting are ancient… something like “C” for “see” and “U” for “you” and all of those, they go back hundreds of years in English” — back, in fact, to Victorian puzzles that were kind of also the first emojis.

As internet language has evolved, abbreviations and acronyms have gone from simple time-savers and fun puzzles to what linguist John McWhorter categorizes as “pragmatic particles,” which serve as empathy markers (“lol” means “I feel you” about as often as it actually means “laughing out loud”) or denote shifts in tone (“hey” has become a way to change topics). Based on my experience with Queer Internet Linguistics, I’d argue that they can do even more. Take, for example, my favorite acronym, which was invented by Autostraddle and has since entered the queer internet lexicon: “ALH” for “Alternative Lifestyle Haircut.”

A Google search for “alternative lifestyle haircut” leads almost exclusively to Autostraddle and similarly queer blogs — if I were to drop it in conversation, my very savvy sixteen-year-old sister probably wouldn’t get it. The phrase codes for a specific and common queer experience, even as the thing it describes gets more and more broadly popular. It’s a way to reclaim a term that has been used to other us — the mundanity of “haircut” offsets the clinical bent of “alternative lifestyle,” and the whole thing together is silly and savvy at the same time. Acronymizing takes it a step further, with its suggestion that this supposedly “alternative” thing is actually so rampant we can get the gist in three letters. Three letters I suddenly want to get carved into my sideburns.

Punctuation

Punctuation was originally invented to help people transcribe speech, but, as Ben Crair points out, “as the written word gained autonomy from the spoken word, [it] became a way to structure a text according to its own unique hierarchy and logic.” Commas go in certain places; semicolons in others. But since texting and online chatting have become stand-ins for speech, punctuation marks do double-duty as tone-denoters and embellishments. The period is angry and the exclamation point is a “sincerity marker.” Ellipses make things more dramatic. The slash has been turned back into a word and repurposed as a sort of duality marker, allowing the public and the private to be juxtaposed in one phrase (“Just got a bunch of work done SLASH watched ten episodes of Words With Girls and inhaled a quart of nutella.”)

Identity-based communities like ours have embraced punctuation for a slightly different reason. While the above marks have been co-opted to indicate defined tones, we’ve adopted some marks specifically because they don’t mean anything specific yet. Take the asterisk at the end of “trans*.” In many command-line interfaces, such as Unix and Microsoft Command Prompt, the asterisk is a “wildcard” character that allows you to make searches with holes in them (for example, if you google “cook * with *” it’ll recommend you some food pairs). Thus, “trans*” has gained popularity as an extra-inclusive word — a way to suggest everything from “trans woman” to “trans man” to “questioning” without the inevitable limitations of actually listing all possibilities. Like the current and controversial movement to reclaim “queer,” it’s a word that tries to skirt what can be hard about words — that they’ve settled into fixed definitions, when groups and identities are often not so fixed.

Portmanteaus

This inclusiveness is also the effect of silly identifier-portmanteaus like “homogay” or “queermo.” They stick because, like “ALH,” they’re both in-the-know and kind of lightheartedly cynical about it, and they work because, like “trans*,” they try hard not to leave anyone out (in this case because they can’t, because they’re made up). (They’re given additional power by a sort of fake-ignorance also found in constructions like “teh interwebs.”)

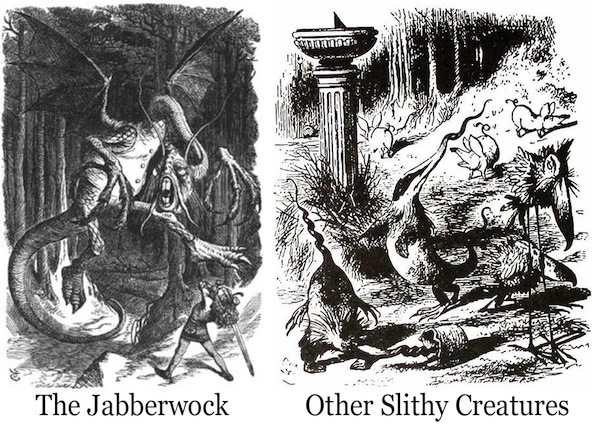

A portmanteau was originally just a suitcase. Lewis Carroll first used it to mean “two meanings packed up into one word” in 1871, in Through The Looking Glass, when Humpty Dumpty is translating the poem “Jabberwocky” for Alice: “Well, ‘slithey’ means lithe and slimy… and ‘mimsy’ means flimsy and miserable!” Children have been bugging their parents with them ever since. As Jen Doll of The Wire points out, the Internet is a great place to sew portmanteaus — they’re easy to make, kind of amusing, and fit well in a hashtag. A ton of the new crop of Oxford Dictionary Online words (“phablet”; “buzzworthy”; “jorts”) are portmanteaus.

Kristin Russo from Everyone Is Gay has seen EIG creations “gaybeans” and “peepsexual” (“meaning you just like people, the end”) take flight beyond their immediate commenter community. Russo credits their popularity with “the fact that the queer community has a much more fluid relationship with language — words mean different things to different people, at different times. Plus we have much more experience with what a word can do — i.e. how “queer” can be incredible to some and horrible to others, or how much power the choice of pronoun can have.” Or the choice between “queerzbian” and “lesbigay.”

References and Catchphrases

Slogans have been around literally forever. “Every social group has its own linguistic bonding mechanism,” as David Crystal says, and there’s no better way to ground yourself in a certain generation or region or other identity subsection than by breaking out a well-timed “what’s the sitch?”.

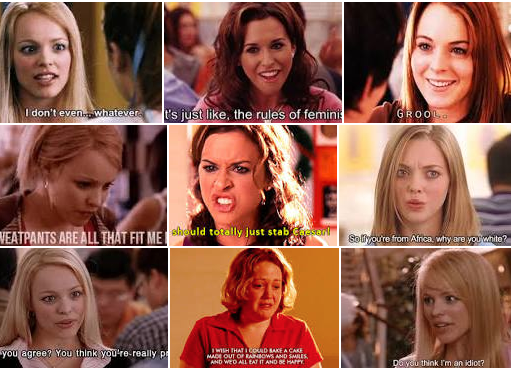

The internet takes this to an extreme. If you were an alien and landed on the comments section of certain websites, you’d be forgiven for thinking all of Earth trafficked exclusively in quotations. There’s a Mean Girls gif economy, at this point.

Unsurprisingly, we have this down, too. Remember who invented “You have a lot of feelings?” It was Shane:

How did it spread? It’s hard to know for sure, but it’s true that our favorite L Word recapper, a certain Riese Bernard, was pretty fond of the phrase. Like most that end up catching on, it seemed to sum up a large, useful idea in the kind of all-purpose small package you can detonate in most social situations. So she started using it in L Word recaps and also in her everyday life, and soon it entered the lesbian lexicon. Is it a direct ancestor of the currently popular “all the feels” and its many variants? Did Tina Fey steal it from Shane? (Mean Girls came out a few months after the critical L Word episode. Just saying). Am I drawn to this conspiracy theory because I want Tina Fey to say it to Shane? It’s hard to know for sure. As Britanni pointed out when I asked her about You Do You (another phrase of uncertain origin), “it’s hard to know exactly where most things started or who deserves the credit, as most sayings aren’t THAT original and can be thoughts that plenty of people have separate from one another… it’s more a matter of who has the power to disseminate it most effectively.”

If there’s anything the queer internet has, it’s disseminating power within our community. We come to the internet to find each other, to feel like a part of something that exists outside of our immediate reach. It’s no wonder we’ve used the tools of the internet to find unique ways to talk to and support each other. Sure, other corners of the web might be sprouting innovations and memes left and right. But when it comes to inclusivity within an exclusive group, we internet homogays have it down.

Comments

this is really super-interesting and thorough thank you for bringing this post into our lives

Thank YOU for bringing a lot of our lexicon into our lives!!

totes my pleasure

i’m trying so hard not to make a cunning linguist joke here.

for real though i don’t know how many words and phrases autostraddle alone is responsible for embedding in my online (and sometimes offline) vocabulary: terrible/awesome, alternative lifestyle haircut, queermo, YOU DO YOU.

“i’m trying so hard not to make a cunning linguist joke here.”

STORY OF MY LIFE

Swear to God, recently went out for a drink with a queer multilingual woman, with a PhD in linguistics. I could barely speak I was so busy trying not to be that girl that made the Cunning Linguist joke.

critters/crittery

i have so many feelings about this post…

I hope you have your all the feelings notebook handy!

most of my feelings have to do with how cute and smart the author of this post is and how much i love our queer community so damn much so yes, luckily i do have my all the feelings notebook handy and yes, i do think i feel a feelings-filled journal entry coming on!

#FEELINGS5EVER

5ever, you guys. Who started that? I only have seen it here on Autostraddle (although maybe it’s because I’m living under a rock?)!

okay @claire7 i investigated and carmen says she stole it from the internet but i am willing to pretend carmen started it if you are. WHO’S WITH ME?!

@floralprintdress Vanessa I am with you 5ever, of course. Carmen is the originator! Carmen is awesome :)

“Three letters I suddenly want to get carved into my sideburns.” Dead. So hilarious.

This is definitely my favorite series on Autostraddle and I feel like my heart is wearing a jaunty little top hat just for you!

i just tipped my invisible top hat to your heart’s top hat.

I feel like queer internet linguistics is just everything I love the most all bundled up together

An interesting entry to your series, thanks.

But I disagree “queer” is somehow an ever-expanding, all-inclusive term. It’s mostly white, overwhelmingly middle class and higher, and rarely used by the most oppressed members of LGBTQIA (most of whom have no interest in ‘reclaiming’ the term or applying it to themselves). Moreover, it has incredibly specific prescribed modes of dress, terminology, speech, education, reading choices, preferred heroes, and even sense of humor. One can view that as a positive (something which binds community) or it can be viewed and experienced as a narrow/oppressive descriptor class.

Moreover, “trans*” was largely dumped onto the trans community by people in the queer community (many of them with no trans history). And what I just said queer also applies to trans* except I feel it has an entire tinge of colonization about it—largely white college kids in Gender Studies departments and LGBT* student unions explaining to a community how it should identify if they want to be respected and not seen as old school.

While I get the need for inclusivity, notice how none of the other ‘letters’ have asterisks. For instance, 95% of the time (yes, I pulled that number out of my behind) let’s be honest, “queer” really doesn’t in any way mean trans, so why isn’t there a “Q” with a little superscripted ‘t’ next to it for queer which is specifically trans-inclusive? Why doesn’t Lesbian have a little superscripted ‘BPQ’ next to it which means bi, poly and questioning women are included? Come to think of it, it should also have a little ‘t’ meaning… not supporting WBW exclusion. How about Q with a little ‘poc’ superscripted next to it, meaning, “we’re queer people but not oppressively white majority controlled and completely open to persons of color?’ There is a VERY specific reason why the asterisk started appearing next to ‘trans’ and it’s not just about maximum acceptance.

hey gina, thanks a lot for this perspective! I didn’t mean to suggest that “queer” or “trans*” unequivocally succeed at being inclusive – just that they were, ostensibly, reclaimed/coined in order to fill what some people must have seen as a need. whether or not we really do need all-encompassing terms (and what a successful one would look like) is a worthwhile conversation for sure.

An equally worthwhile discussion would be who gets to coin terms, who gets to ‘control,’ market and repackage them, how the assumption of their meaning doesn’t match the reality, for whom are they really intended, and how their meanings change depending on the audience. The thing about language is as much as it supposedly clarifies, it just as much obscures. (and no, I’m not a semiotics nerd).

I agree that neologisms can be confusing: whenever I see trans*, I still spend a minute or two looking for a footnote before I remember that that’s not what the asterisk indicates.

Also, I would very much like the opportunity to use superscripts and subscripts. I’m rather bummed that their respective HTML tags are not included among those we can now use in these comments.

That is an interesting point. I’ve been thinking about who controls language lately with regard to the term “LGBT”. I’ve become increasingly dissatisfied with the acronym because it suggests a hierarchy with lesbians and gay men given top priority, bisexuals in the middle, and transgender people basically an afterthought. The other letters (Q, I, A, etc.) that are sometimes added are not even understood by most people outside of queer and trans communities. I’m on the lookout for a better term that is inclusive without being problematic, but I’ve yet to hear something that really seems appropriate. Maybe “gender and sexual minorities”?

I’ve heard and sometimes used sexual minorities. I’m sympathetic toward the impulse to add gender, but the result sounds awkward as is: what we really need is a denominal adjective, but there isn’t any in common use. Perhaps a neologism—genderal, maybe?—is in order.

Another solution is to use a circumlocution such as acronym folk or people of acronym. That way, no one need worry about the precise letters constituting the acronym or their order.

This is by far the most interesting of all the things I’ve tead today (which just happen to includes 8 academic articles on entomophagy (eating insects as a food))

a great compliment as I’m partial to roasted crickets

I started saying “totes” as a joke after reading some everyoneisgay posts but it’s begun an inevitable creep into my lexicon, despite my resistance. “Want to go out tonight?” “Totes…FUCK”. A very strange experience indeed, it’s as though the words have a mind of their own. I totes need help you guys. CURSE YOU DANIELLE & KRISTIN, you gorgeous gaybeans.

ha! “totes” started in 2006, i used it on autowin and in L Word recaps and it was also employed with regularity on gawker media sites. now it’s still funny to use every now and then

Omg I do the same thing, I picked up “peeps” from Kristin and Dannielle too, and I got the weirdest looks from my family when I visited them over Thanksgiving.

This happened to me with “probs.” It gives me all teh feels. ;)

Thank you for this article. I am always keen to geek out over words, particularly when there’s a queer context.

I’m also confident that the queer internet (and Autostraddle in particular) has enhanced my vocabulary and helped me develop the ability to describe my own existence. The queer internet has given me super important verbal tools that I once lacked, and I’m so grateful for that.

This is so many things that I love.

I love the beautiful coded nature of all this queerspeak we’ve built up around ourselves and the way it influences our real life vocabulary and vice versa.

This ties in really well to Carmen’s post today about dressing a certain way and suddenly being invisible to your community. It has always made me incredibly happy to know that, beyond the visual signals and the “I see you, seeing me” looks, we have this way that our language sets us apart in the eyes of one another, while going unnoticed to the to the oblivious straight people viewing these exchanges.

hey, did you mean gabby’s post? because if so I was thinking the same thing! thank you for the lovely comment

Aww, you’re so welcome. And yes, I did mean Gabby, sorry! Redesign day means I’ve been on more of an AS binge that usual today, everything is getting muddled in my brain!

Also I <3 David Crystal in a big way, so you calling him the OG of internet linguistics was perfection.

Mind blowing. SO many feelings. I can’t even. Shane, you did more than make straight girls question their sexual orientation, you were ahead of your time. Hats off.

I (just) have (a lot of) strongly positive feelings about internet linguistics so this post is basically like the best Hanukkah gift of all time

This is my favourite ‘More Than Words’ so far! It makes me feel like I’m part of a secret club.

All I could think of when I saw your comment was:

Every time I see You Do You on some other website I assume they stole it from Autostraddle. I also get confused when people don’t know what I mean by Alternative Lifestyle Haircut.

Sames! And whenever it slips out to some relative who I’m not yet out to I always think oh shit, was that a really gay thing to say and that they’ll know where I got it from. It’s weird the associations we make with words that don’t really mean much to people outside the Autostraddle or internet community.

I say “You Do You” in every part of my life all the time. I don’t mind if that concept stops being part of our secret club and starts being a thing we can all get behind :)

I would say you do you more often, but I’m concerned people will interpret it as being synonymous with go fuck yourself.

Me too!

I loved every bit of this. Thank you for all of this amazing information :)

I love this series and this article! Sometimes I don’t even remember that some of these terms are not universally understood.

I always have this experience with the term “LGBT.” When people are confused by it or just use “gay” as an umbrella term instead, I’m always like, COME ON PEOPLE but I guess there are a lot of people who don’t hear/use that term very often.

I’m perennially worried that new letters have been added without me being informed. Last I heard it was LGBT*QIA. Some people, though, prefer QuILT*BAG, because you can pronounce it as two syllables instead of seven, but what happens when the next letter gets added? The whole thing will have to be rearranged once more.

Yeah sometimes I’ve seen it as LGBTQQIAA with the q’s for both queer and questioning and a’s for ally and asexual. Maybe there should just be superscript 2s as in q squared. LGBTQ2IA2!!!

I work under the assumption that, as in BDSM, any of the letters can do double (or, for that matter, triple, or quadruple, etc.) duty. As such, it would make the most sense, as a precautionary measure, to use the entire alphabet, thus ensuring the inclusion of any new identity that may arise.

Loved this one. I noticed all the “internet linguistic” articles lately. By far this is my favorite of them all.

I haven’t even read the article yet but can we just acknowledge how ridiculous it is that CNN said that selfies were “the most embarrassing phenomenon of the digital age”.

I love this column. thank you!

How did it take me 25 installments to find this? So pumped! This will make me feel like I am putting my linguistics degree to good use :)

Personally, I always find myself falling into big holes of internet talk lying around on the web. None have been more irritating to me than doge talk. I CAN’T STAHP. When I saw the new haircut AS got my first comment was..

Such gayes.

Much deezeyen.

Wow.

Then I quickly erased it and put something in all caps.

very blog

so straddel

This is fantastic and I wish it had magically existed about 9 months ago when I finishing up my dissertation because then I totally could have cited Autostraddle twice! A missed opportunity to be sure. Great job!

Loved this read. Explained and learned some things I have often wondered about.

But being not lingo-savvy, I’m still confused by how some words should sound… like lesbigay (les-be-gay vs les-bye-gay), or gaybeans (gay-bians vs gay-beans…:p personally I hope its the latter)?

Can someone invent a new cute queer word with “nugget” in it now? I want a legit reason to say it out loud :p

Boinugget- The Polly Pocket of genderqueers. A compact package of androgynous sexy time.

Plural: boinugz

Usage:

“Check out that hot little boinugget over there! I bet they would climb me like Everest.”

“I need to break me off a piece of that boinugget. God damn!”

Or something.

Oh wow. Leah. That is good! Love that plural form too XD

I’m just going to go ahead and start sprinkling some “boinugz” into comments and convos now… I’ll be sure to reference you when oxford dict comes knocking.

i just call people “nugget” or “nuggets” like it’s normal? admittedly i did this more in high school but i would be willing to bring it back in full force. for example: “oh my god look how cute you are, what a little nugget!” “hey nugget!” “ugh you guys are such adorable nuggets.” “hi nug.” very versatile, makes me crave chicken nuggets, super adorable, into it.

“Nugget” has long been one of my favorite pet names for people. That shit sounds adorable as hell.

great article!

another one that (i think?) can be attributed to riese: botp

And let’s not forget Evan Rachel Wood Bisexual!

I shit you not…when I first started my current job I was talking to one of my younger co-workers and I made a comment on something we were discussing. She stopped for a second, looked at me, and asked “Are you on Tumblr? You just sounded very Tumblr.”

It’s taken over. It’s taken over my everyday speech.

LOVE THIS. Interesting, well written, smart. Love.

Internet and language things are so crazycool.

guys i feel really self conscious now

I’m really concerned about my slithy jorts, though

love this

I’m so proud to be one of us making this queer lexicon happen!

Favorite more than words ever. So good.

As a queer languages student who definitely spends too much time on the internet, this article is 100% a summation of my personality/something I will probably spend a lot of time and effort studying one day :D