***This is part 2 of a 2-part series! Part 1 can be found here.

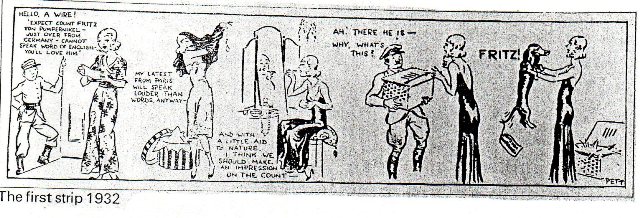

When we last left off, “gay” was suffering from a bad case of vertigo after a centuries-long roller coaster ride, and had landed temporarily on “sexually promiscuous” as its most common meaning. By 1800 or so, to hammer a metaphor, the word was also experiencing a sort of gender-based tilt. As Mr. Wainscotting over at MissingSparkles points out, gay-as-promiscuous took on different flavors depending on the gender it was referring to — just as the idea of promiscuity has always taken on different flavors depending on the gender it refers to — so while a “gay man” was a Don Juan, a “gay woman” was a sex worker. Over time, these two feelings of “bachelor” and “deviant” started to meld together, something that might have aided the definition’s trajectory. See, for example, Jane Gay, the “heroine” of a British comic strip from 1932-1959 — she was a single woman who was always losing her clothes.

Meanwhile, across the pond, “gay” was gathering entirely different connotations. Starting around 1893, “gay cat” was itinerant slang for — in the words of Leon Ray Livingston, aka “America’s Most Celebrated Tramp” — a good-for-nothing young loafer. A gay cat would “work maybe a week, gets his wages and vagabond about hunting for another ‘pick and shovel’ job… cats sneak about and scratch immediately after chumming with you and then get gay (fresh). That’s why we call them ‘Gay Cats’.”

Gay cats were looked down upon by other wanderers — as scholar John J. McCook described in 1893’s “The Public Treatment of Pauperism,”, they were like “a jackal following up the king of beasts.” The hierarchy was such that you could skip this step if you had started young (Jack London, for example, went straight from “road kid” to “profesh”). By the 1930s or so, gay cats were also known for providing sexual favors for more established itinerants in exchange for food and protection. A 1933 dictionary of “underworld and prison slang” defines “gey cat” as “a homosexual boy.”

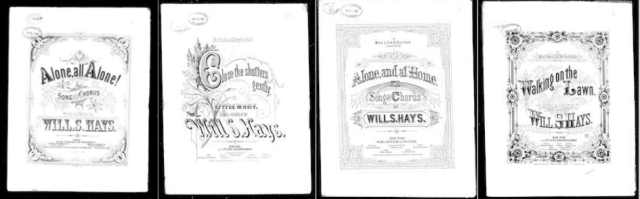

Meanwhile meanwhile, said “homosexual boys” and their adult counterparts were were also using the word to refer to themselves and each other. As usual with terms used mostly in private, the exact trajectory of this one is hard to pinpoint — closets are dark, and the flashlights of history are flickery. Luckily, enterprising writers and humorists were able to take advantage of the word’s many meanings (and therefore its attendant ambiguity) for nudge-nudge wink-wink purposes, so there are a few public examples we can use. A popular song in 1868 called “The Gay Young Clerk in the Dry Goods Store,” written by William Shakespeare Hays, refers to a eyeglass-wearing moustachioed young man who is “nobody’s beau” even though he “smiles at all the girls he meets” (the association is kind of a stretch — and I can find no corroboration for the ubiquitous claim that the song was often sung by drag performers — but I couldn’t resist bringing yet another William Shakespeare into this).

Gertrude Stein’s 1922 prose poem “Miss Furr and Miss Skeene,” based on the real-life couple Ethel Mars and Maud Hunt Squire, uses the word “gay” 136 times. Stein’s poetic technique famously made use of repetition in order to encourage readers to really hear words — “Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose” is hers, too — and by hammering on a fraught and multifaceted word like “gay,” in the context of this love story between women, she encourages her readers to let it fracture into all its attendant meanings. (N.B.: No one excerpt does this poem justice, so I encourage you to read the whole thing.)

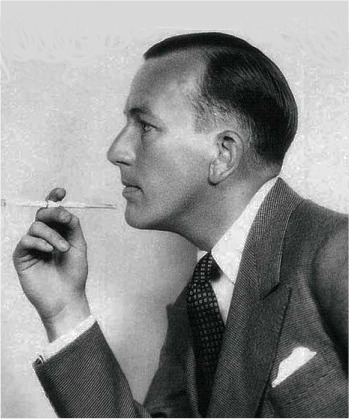

Even less ambiguous was Noel Coward’s song “Green Carnation,” from the 1929 operetta Bitter Sweet, a comical love story set in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Although Coward never came out during his lifetime, he’s now a gay icon, and he clearly had his finger on the pulse. “Green Carnation” is an ensemble piece sung by “blase boys” describing how they are “exquisitely free / from the dreary and quite absurd / moral views of the modern herd.” The last line — “And as we are the reason for the nineties being gay / we all wear a green carnation” — cheekily reattributes the credit for the term “Gay Nineties,” and cites Oscar Wilde’s trademark flower as a symbol of a certain kind of art-loving gay man from that earlier era.

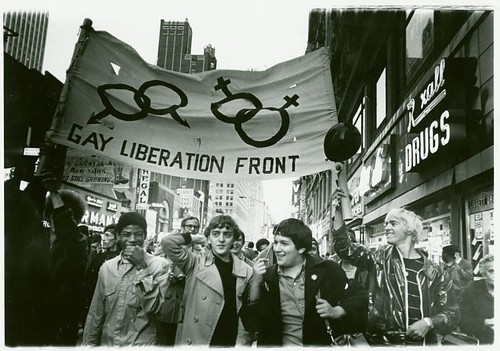

But Stein and Coward were both gay themselves — when did the word start showing up outside of its in-group? According to some, when Cary Grant yelled “I just went GAY all of a sudden” while jumping up and down in a women’s bathrobe in 1938’s Bringing Up Baby, the word was in wide enough usage that it counted as a double-entendre — savvy audience members would pick up on the implication, while censors let it by because it technically just means extra-joyful. Psychologists began using the word (albeit in scare quotes) while writing about their patients in the late 1940s. As of 1955, British journalist and gay activist Peter Wildeblood defined the word as “an American euphemism for homosexual.” Around this time, the activist community — which, during the 1940s and 50s, had overwhelmingly organized around the word “homophile” — began referring themselves instead as “gay,” “lesbian,” “LGBT,” and other terms that have stuck around since. By the time the Stonewall Riots garnered the movement widespread attention, the switch was complete.

Over the next few decades, this version of “gay” took off, joining the vernacular to such a degree that older meanings were overshadowed. It became (and remains) the preferred term for what it is — a 1991 report by the American Psychological Association recommends it over the more offensively clinical “homosexual,” and the more recent GLAAD Media Reference Guide agrees, adding that “queer” hasn’t caught up. But the roller coaster ride was not (and is not) over! Starting around the 1970s, kids started using it as a pejorative (i.e. “that’s so gay”). This kind of usage ramped up in the 1990s and continues today, to such an extent that some groups (the Apple dictionary; the BBC Board of Governors) consider it an entirely different and unrelated word (luckily, others recognize it as the microaggression it has been proven to be).

And so, centuries after its whirlwind beginning, “gay” continues to tug in and out of the mainstream. As of January 24th, President Obama had used the word on the record 272 times — fifty-six more than President Clinton (it might not be enough to earn him the title of First Gay President, though). That same week, Coca-Cola was called out for banning the word on some kind of virtual can-scribbling promotional website. It’s been a long journey for three little letters. It’s a good thing words don’t get worn out.

This has been the thirtieth installment of More Than Words, where I take queer words of all sorts and smash them apart and see what makes them tick. Every week I dissect a different word, trying to figure out where it came from, how it has evolved, where it might be going, and what it all means. It’s like reading the dictionary through a prism. Feel free to send word suggestions to cara@autostraddle.com.

Header by Rory Midhani

Comments

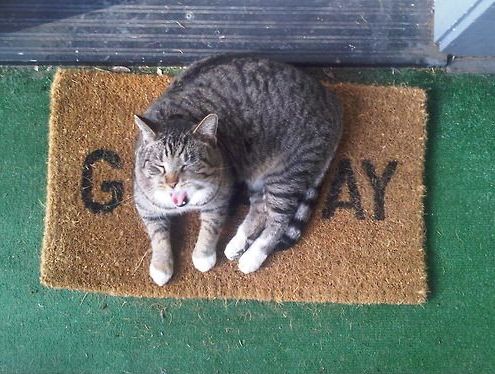

All the best etymologies involve cats. Although I’m still not quite sure what to think about this: “cats sneak about and scratch immediately after chumming with you and then get gay (fresh).” Is he still talking about people here? Or actual cats? Or both? I have the scars to prove that my feline companion sometimes scratches immediately after “chumming” with me, but he has never subsequently tried to get “fresh”, at least not in my understanding of that expression. That would just be weird.

Words with cats! Just when I thought I couldn’t enjoy this column any more than I already did…

Huh. I knew that “that’s so gay” was older than the late 90’s, but I didn’t think it went back past the 80’s.

you know i love anything involving gay cats.