If you’re reading this website, chances are someone, at some point, has asked you how you came out. And maybe you’ve told them. Maybe you’ve shared the story with a close friend as part of the bonding process. Maybe you wrote it down in our open thread. Maybe you reenacted it in front of a campfire to howling applause. Coming out — and its supposed opposite, being in the closet — are major plot points in the stereotypical queer narrative, so much so that it took me a while to realize that someone, at some point, must have actively differentiated and named them. After all, it seems so obvious, right? But if I’ve learned anything from writing this column, it’s that the metaphors that seem most natural are just as constructed as the rest. So I decided to throw coming out a coming out party.

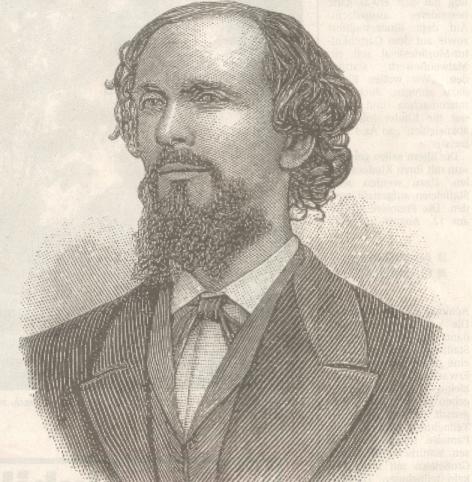

The idea of “coming out” is much older than the phrase, and so are its much-touted psychological and political benefits. German gay rights activist Karl Heinrich Ulrichs (who has been called “the first gay man in world history” — hyperbolic, but hey) was forced to resign his position as a public legal adviser in 1857, after a colleague found out he was hooking up with guys. This gave him pause, and he devoted the rest of his life to gay rights, publishing a variety of papers under the pseudonym Numa Numantius, coining a bunch of (now-outdated) phrases to describe his own feelings and observations, and speaking out against discriminatory laws. One of these papers urged queer people to “self-disclose,” that they may lead freer lives and make the whole concept less publicly invisible. Heinrich himself had done so in 1867 in front of the German Association of Jurists, asking his colleagues not to adopt Prussian anti-gay sanctions when rewriting their constitution. Although he was unsuccessful and eventually exiled himself to Italy, he was forever happy that he had “found the courage to deal the initial blow to the hydra of public contempt.”

Iwan Bloch, a Jewish-German doctor, counseled his older patients to come out to their family members in 1906 (Bloch did a lot of other cool things too — he’s often considered the first sexologist, and Freud credits him as the first person to study same-sex attraction from an anthropological standpoint, rather than a pathological one, which makes him decades ahead of his time). And in his 1919 classic The Homosexuality of Men and Women, Magnus Hirschfeld, a sexologist and gay rights activist, describes several efforts by activists to try to leverage coming out for political reasons:

“Homosexuals and their spokespersons have repeatedly tried to move Urnings to give their names to the police voluntarily. One lady wrote from America, “Inverts should take courage and independently declare themselves as such and ask for an examination and an investigation”… In Vienna, K. Kraus considered these thoughts more seriously, saying: “I am of the opinion that a victory can be won over the [law] if the most famous homosexuals openly admit to their fate.” Hirschfeld agrees that it would work well, but says that these suggestions ignore the fact that gay peoples’ “internal and external inhibitions” will prevent them from actually following through.

(Long sidenote: In 1905, members of The Scientific Humanitarian Committee (which was started and run by Hirschfeld) “proposed that one thousand homosexuals denounce themselves to the district attorney because of crimes against [anti-gay laws]… but at the same time make conviction impossible by witholding [details].” The reporter covering the story suggested instead that “one thousand nonhomosexual friends of the movement should get together and denounce themselves at the district attorney’s office for [the same crimes]. The district attorney’s embarrassment would be the same — but the safety and confidence of the persons denouncing themselves would be significantly greater.” Sounds like the same arguments about ally’s actions have been going on for hundreds of years.)

The first already-famous person to publicly come out for its own sake, rather than to accomplish something else, was poet Robert Duncan, who did so in 1944 in the context of an essay called “The Homosexual in Society,” which was published in the magazine Politics. Duncan, in an introduction to a reprint a fifteen years later, wrote that the essay “had at least the pioneering gesture, as far as I know, of being the first discussion of homosexuality which included the frank avowal that the author was himself involved,” setting the precedent for later generations’ award acceptance speeches and tweets and Sports Illustrated articles and television episodes nominally about puppies.

But none of these early people called what they were doing coming out — they, and others outside of the public eye, talked instead of “wearing a mask” and/or letting that mask fall away, wearing their hair up or letting it down, or “dropping hairpins” — clues that only other gay people would pick up on. In his book Gay New York, historian George Chauncey traced the phrase “coming out” back to American gay society in the 1930s, when it had a very different connotation than it does now:

“Like much of campy gay terminology, “coming out” was an arch play on the language of women’s culture — in this case the expression used to refer to the ritual of a debutante’s being formally introduced to, or “coming out” into, the society of her cultural peers. (This is often remembered as a ritual of WASP high society, but it was also common in the social worlds of African-Americans and other groups). A gay man’s coming out originally referred to his being presented to the largest collective manifestation of prewar gay society, the enormous drag balls that were patterned on the debutante and masquerade balls of the dominant culture and were regularly held in New York, Chicago, New Orleans, Baltimore, and other cities.”

So originally, “coming out” wasn’t about leaving a dark, secret closet, or exposing yourself to the larger world — it was about entering a welcoming society of your peers, and all the partying that implied. As the GLBTQ dictionary puts it, before the Stonewall Riots, “the term signified a coming out into a new world of hope and communal solidarity.” Even straight people knew it in this way — psychologist Evelyn Hooker, whose research helped persuade professionals that being gay isn’t a mental disorder, introduced the term to the academic community in 1965, describing it as “when [a gay person] identifies himself publicly for the first time as a homosexual, in the presence of other homosexuals, by his appearance in a bar.”

After Stonewall, though, the mood changed. New political awareness reintroduced the urgency recorded by Ulrichs and Hirschfeld. The closet was born, a place full of skeletons. Protesters came up with a chant — “out of the closets and into the streets!” — and Harvey Milk gave his Hope Speech. We eventually got a National Coming Out Day, in 1988. The Human Rights Campaign has a Coming Out Center (at least on their website). If it’s safe, people encourage, help yourself, leave the scary closet, and change the world by doing so.

All of that is, of course, really valid. Coming out is a powerful political tool. Hirschfeld’s wish, that “one thousand homosexuals” show their faces en masse and render the laws against them ridiculous, is slowly but surely coming true. Watching people come out earlier and more often, and watching reactions grow more and more positive, is a great societal barometer. The process continues to be an extremely important part of personal queer narratives. And studies have shown that, in most situations, it’s healthier and less stressful to be out.

But learning its more celebratory history, which surprised me greatly, made me think that we should try to get a little of the party back. People who come out, no matter on what scale, are brave and strong and hopefully will change the world. But they also get to join an awesome community. That part of it often gets lost in the billions of thinkpieces about what it means to have a queer football player, a queer news anchor, another queer Ellen. Maybe it’s time to reclaim coming out.

This has been the thirty-second installment of More Than Words, where I take queer words of all sorts and smash them apart and see what makes them tick. Every week I dissect a different word, trying to figure out where it came from, how it has evolved, where it might be going, and what it all means. It’s like reading the dictionary through a prism. Feel free to send word suggestions to cara@autostraddle.com.

Header by Rory Midhani

Comments

What an incredible piece to wake up to! Thanks for this Cara

I’ll bake the cakes if you grab the alcohol – lets put the party back into it for all the baby gays!

This is probably weird, but I honestly am not sure who I first came out to or exactly when it was – and it was only within the last 3 years or so! It was probably my sister. Or my mom. Or maybe a friend? I can’t remember! I do remember that it was scary the first few times, but now feels (usually) pretty casual and relaxed, which is nice. I’m still not 100% out because of work-related reasons (for instance, I’m not officially out on FB, though I did post a celebratory status about Ellen Page!) But all of my close friends and medium-close friends know, as well as quite a few other people.

I would like a party, though. I do think that tradition should be revived.

Amen! I wish someone had thrown me a party or something when I came out, because that shit ain’t easy. From now on, coming out parties for everyone.

Sounds good to me!

I’ve actually been thinking about this kind of thing recently. When I came out I felt very much on my own: my friend group was entirely heterosexual, my father was suspected to be homophobic, I only knew a handful of gay people and none of them were people I really knew enough to turn to… and when I did start meeting and befriending gay people there was this huge disconnection that made me think something was wrong with me. It wasn’t until over a year after I came out that I started to find my place within the queer community.

It sucks because sexuality should be this cool, fun thing and not just a battle. There should also be cake (preferably with rainbows and possibly vegan).

Ugh, html tag fail. The above comment is my own words in response to this quote from the article:

“we should try to get a little of the party back. People who come out, no matter on what scale, are brave and strong and hopefully will change the world. But they also get to join an awesome community. That part of it often gets lost in the billions of thinkpieces about what it means to have a queer football player, a queer news anchor, another queer Ellen. Maybe it’s time to reclaim coming out.”

I love that we get to come out. That, at some point, we get to choose to be our most authentic selves. It makes me so thankful sometimes, when I’m with my girlfriend, that while being queer wasn’t a choice, voicing it was. And with it comes love. Not just of my girlfriend, but of the queer community too.

This is so cool and well-researched! Thank you!

I love this piece! I agree, the choice to be who I am has been so freeing. I have the most supportive girlfriend in the world. When I am with her the world is a better place. I love us and I love me. I don’t have a gay community to be apart of. I live in a small southern town and there would be consequences for my family if I were to fully come out, so when I’m here I have to be more closeted, but when I’m with her I can be 100% open about who I am. She has an amazing support system in her family and friends who have welcomed me with open arms and I am blessed to have her in my life.