Welcome to the twentieth installment of More Than Words, where I take queer words of all sorts and smash them apart and see what makes them tick. Every week I’ll be dissecting a different word, trying to figure out where it came from, how it has evolved, where it might be going, and what it all means. It’s like reading the dictionary through a prism. Feel free to send word suggestions to cara@autostraddle.com.

Header by Rory Midhani

Last time on More than Words, we finished up a three-part series on gendered pronouns in English — where they came from, where they are now, and where they might be going. But what about the many, many aspects of language that are implicitly, rather than explicitly, gendered? Words or phrases so culturally tied to one side of the binary that we fill them in automatically, the way your brain grabs at a cliché simply because it’s at the front of the mental shelf? Why does that happen? How does it effect us? Should we try to change it? Can we, even if we try?

This question briefly made some corners of the news this week after author Jennifer Weiner took critic Alexander Nazarayan to task for describing her own criticism of the New York Times Book Review as, among other things, “strident.” “Can anyone remember the last time the word “strident” was applied to a man?” she tweeted. Many of her followers chimed in with excellent snark, and more examples of words that are disproportionately used to describe women, usually in order to shame them into being quiet.

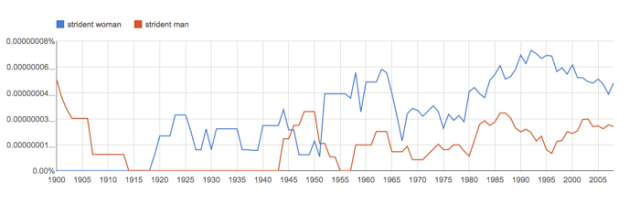

Weiner and Nazarayan had a phone conversation, and an essayistic back-and-forth hosted by The Atlantic (Weiner: “Make a point, and you’re ‘combative’ or ‘polarizing.’ Disagree with someone, and it’s not a ‘debate’ or a ‘discussion,’ but a ‘cat fight’ or a ‘feud.’; Nazarayan: “Had I been aware of that connotation while writing this post, I would have used another word”), and Nazarayan removed the word “strident” from his original essay (the tone of which is, hilariously, pretty strident). Slate’s Amanda Hess backed up Weiner’s hunch with hard data from the Google Books Ngram tool, which charts the usage frequency of words and phrases in published works over time:

“Over the past century, published books cataloged by Google refer to a ‘strident woman’ more frequently than they do a ‘strident man.’ That’s particularly significant given that books talk about men in general a lot more than they talk about women… In the 1930s, books referred to a ‘strident feminist’ more than it did a ‘strident critic.’”

How did this happen? Dictionary definitions of “strident” never mention gender at all. Etymologically, it’s probably just onomatopoeic, as it comes from the Latin “stridere,” which means “to make a harsh noise.” From there it jumped to French, and then English, where it still means essentially the same thing — although, especially in contrast with its more scientific cousin “stridulent,” it has taken on pejorative connotations. Mix all this up, spread it over years of cultural conditioning, and suddenly every woman in an argument is somehow making a horrible screeching sound, audible even over Twitter.

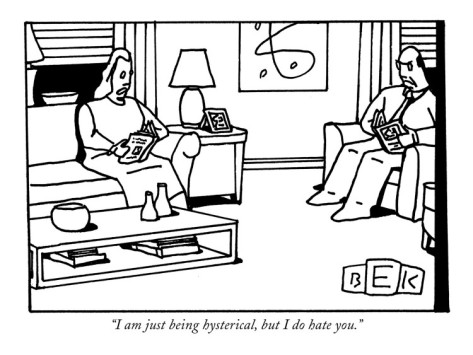

“Strident” is, of course, not the only example of this phenomenon. Plenty of words, for no clear linguistic reason, have become stuck on one side of the fence. I ran a few Ngrams myself and got some (sadly) unsurprising results: the corpus is teeming with shrill, nagging, and irrational women, but their male counterparts are nowhere to be found (not to mention the insane, more historically rooted sexism of language surrounding insanity —”hysterical” and “loony” are both literally named after female biology — which deserves its own column).

But come on, now, says the devil’s advocate on my shoulder. Does it really matter? Sure, humankind’s habit of referring to women as “strident” or “shrill” when they mean “not making sandwiches” reflects societal viewpoints that should be examined, set on fire, and fed to wolves. But does it actually reinforce those views? Yes, actually — because the human brain is instinctively addicted to categorization and will grab at any excuse to sort into boxes (readers of this site are likely all too familiar with the cultural and political consequences of this). Language is no exception — as anyone who has ever been on either side of a flubbed pronoun knows — and recent experiments back this up, both results-wise and in their very construction.

Research by cognitive scientist Lera Boroditsky and linguist Dan Slobin both suggest that certain adjectives are so firmly associated with certain genders that they cling to them even when said genders are merely grammatical. In Boroditsky’s tests, German and Spanish speakers were asked “to describe objects having opposite gender assignment in those two languages. The descriptions they gave differed in a way predicted by grammatical gender. For example, when asked to describe a ‘key’ — a word that is masculine in German and feminine in Spanish — the German speakers were more likely to use words like ‘hard,’ ‘heavy,’ ‘jagged,’ ‘metal,’ ‘serrated,’ and ‘useful,’ whereas Spanish speakers were more likely to say ‘golden,’ ‘intricate,’ ‘little,’ ‘lovely,’ ‘shiny,’ and ‘tiny.’” Slobin did the same thing, but used newspaper articles instead of live subjects, finding that press coverage of a new bridge — the Millau Viaduct, which stretches from Paris to Montpellier — described it entirely differently depending on whether the reporter wrote in German (where the word for “bridge” is feminine) or French (where it’s masculine).

Fascinating, to be sure. But even more fascinating, to me, is what these studies themselves assume. When writing about this, people tend to focus on the fact that these inanimate nouns are being described “femininely” or “masculinely,” taking an attitude of: How crazy! How ridiculous, the human need to personify! No one — not even the scientists in charge of the experiments, who are literally doing them in order to see how language affects the brain — seems to think twice about the adjectives doing the describing, and our implicit gendered categorization of them based on superficial, outdated, and often problematic stereotypes. Our overwhelming tendency to refer to a bridge as “slender” when we think of it as grammatically female seems to me less interesting than our tendency to think of “slender,” itself an inherently neutral adjective, as feminine in the first place. I want to see some studies on that, pronto. Otherwise I fear we are doomed to a future of strident, hysterical bridges.

**special thanks to reader Amy Dentata, whose comment got me thinking about this!**

Comments

Double standards everywhere! I also have been thinking lately that when a man is talking about his feelings, he gets described as “sensitive” “communicative” or “brave” and when a woman is talking about her feelings she is likely to be described as “overemotional” “needy” or – my all-time least favorite word to be called – “crazy.”

OR maybe that’s just me lol.

“”Can anyone remember the last time the word “strident” was applied to a man?” she tweeted. Many of her followers chimed in with excellent snark…”

Another one…can anyone remember the last time “snark” was used to describe a man? I use the word ‘snark’ all the time and I was just now realizing I don’t usually apply it to a man. I didn’t even think of it until reading that sentence, even. It’s so unsettling how invisibly gendered some words are.

In my experience, I hear “snark” used to describe comments that men make more often than women. The same comment from a woman would be labeled “bitchy”. The joys of double standards!

Interesting. I generally hear “snark” used as more ‘polite’ version of “bitchy,” and still directed at women. Like…if someone wants to say “bitchy” but doesn’t want to come across as sexist and/or mean…then they’ll use “snarky.”

You’re right… the word that comes to mind as a “masculine” equivalent is “sardonic”, not nearly as pejorative.

I hadn’t really thought about the word strident in particular, but I will say, when I learned a foreign language for the first time it floored me that objects were usually masculine or feminine, and not because, like some of my classmates thought, it was overly complicated, but because it seems so weird to apply gender to something.

I really liked this, it’s an interesting topic

this is really interesting! i actually had assumed that shrill was a gendered word — like that somewhere in its definition it was a word specifically for females. which proves your point gamely!

I was called shrill just yesterday; I’d be annoyed, but sometimes it’s easier to just know you’re dealing with a raging misogynist.

What I really hate is when a woman is called crazy.

men calling women crazy is my #1 pet peeve as well. especially when the people in question know one another personally, i find it usually means, “i did something to upset this woman and then she had feelings about it that were inconvenient to me,” and then i always want to say, “you know, that doesn’t make the woman crazy…it makes YOU an asshole.” sigh.

And they never get called on it! It infuriates me.

This is really interesting. I know a lot of people think all the gendered nouns in other languages are weird and to some extent I agree, but actually one of the things I’ve liked about learning Spanish is the adjectives used with these nouns seem to be more interchangeable. Like hermoso/a, guapo/a and bonito/a (all roughly translating to pretty/beautiful/handsome) are used to describe both guys and girls, masculine and feminine objects, whereas in English you’re more likely to say a girl is pretty and a boy is handsome.

My Spanish isn’t good enough to make any more extensive examples but I reckon there’s definitely more to this gendered language than you might think initially

that is very cool and awesome and counterintuitive.

i have been thinking a lot lately about how Britney Spears likes to call boys “pretty”

she is a gender warrior

How we refer to men or women in spite is one thing – even more harmful (and hidden) is the gender bias in letters of recommendation.Do check out this awesome (or horrifying) study: http://www.ncwit.org/sites/default/files/legacy/images/practicefiles/AvoidingUnintendedGenderBiasLettersRecommendation.pdf, or the original paper: http://das.sagepub.com/content/14/2/191.abstract.

this is a great article and something i have been thinking about a lot lately struggling with my christian upbringing. i no longer want to call myself woman, nor man, or even human, i’d prefer earthling! i was brought up to say, at the end of a prayer to a male gods, “a-men”. what would the world look like if today’s ruling religions praised womyn gods as creators? my spiritual self has been rolling with that one lately.

also,

i lived in rural spain for a year and had a very difficult time with the language and the culture because of the gender dichotomy. i was constantly questioning why certain objects were masculine or feminine, because i just could not see a gender identity in the objects, or i would assign my own gender identity to the object (!). do you think that to remember the assigned gender of certain objects requires, as you mention, ascribing certain characteristics that are traditionally related to that gender to the object i.e. the “intricate, shiny knife”? is that is how the brain forms connections and solidifies the concept? if that’s true then gendered language kind of fucks up if you THINK of gender.