The Gaslight Café, where The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel‘s eponymous plucky heroine gets her unexpected and highly intoxicated start as a stand-up comic and her eventual manager Susie Myerson is vaguely employed, was actually a real place in New York City. A fixture of New York Bohemian life and the official “Beat Mecca,” the basement of 116 MacDougal Street was the go-to spot for readings by sexually fluid poets like Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac and Diane di Prima. In the ’60s, folk musicians and comics were added to the busy nightly line-up.

The Gaslight was not only located in Greenwich Village, an epicenter of gay and lesbian life in New York at the time, but also in a specifically lesbian section of Greenwich Village. Swing Rendezvous, a jazz club and lesbian bar visited by Audre Lorde and Kitty Genovese, was directly across the street at 117 MacDougal and attracted a mostly-white working-class clientele who adhered to strict butch/femme roles. The Portofino, an Italian restaurant with an unofficial Lesbian Night on Fridays where Lorraine Hansberry often turned up and Edie and Thea met, was a three-minute walk from The Gaslight, as were lesbian bars Pony Stable Inn, The Laurels and Provincetown Landing, a regular haunt for Patricia Highsmith. A 1955-56 F.B.I. investigative report of The Gaslight’s neighborhood declared, “a majority of the bars and restaurants in this area cater to lesbians and homosexuals.” Just around the corner from The Gaslight, Tony Pastor’s Downtown had a mixed clientele of “lesbians and tourists, some gay men, and female impersonators.” (It’d shut down in the ’60s and would consequently host meetings for The Gay Liberation Front and The Radicallesbians.) Next door was The Music Box, another “notorious… place of amusement” for gays and lesbians.

Buddy Kent, a lesbian who did drag shows in the neighborhood in the ’50s, said the area “was home. and we had the best protection in the world from the Mafia. They ran everything.” Still, raids were common, and an arrest, followed by your name in the paper the next day, could ruin your life. So the culture was underground but very visible if you knew what to look for.

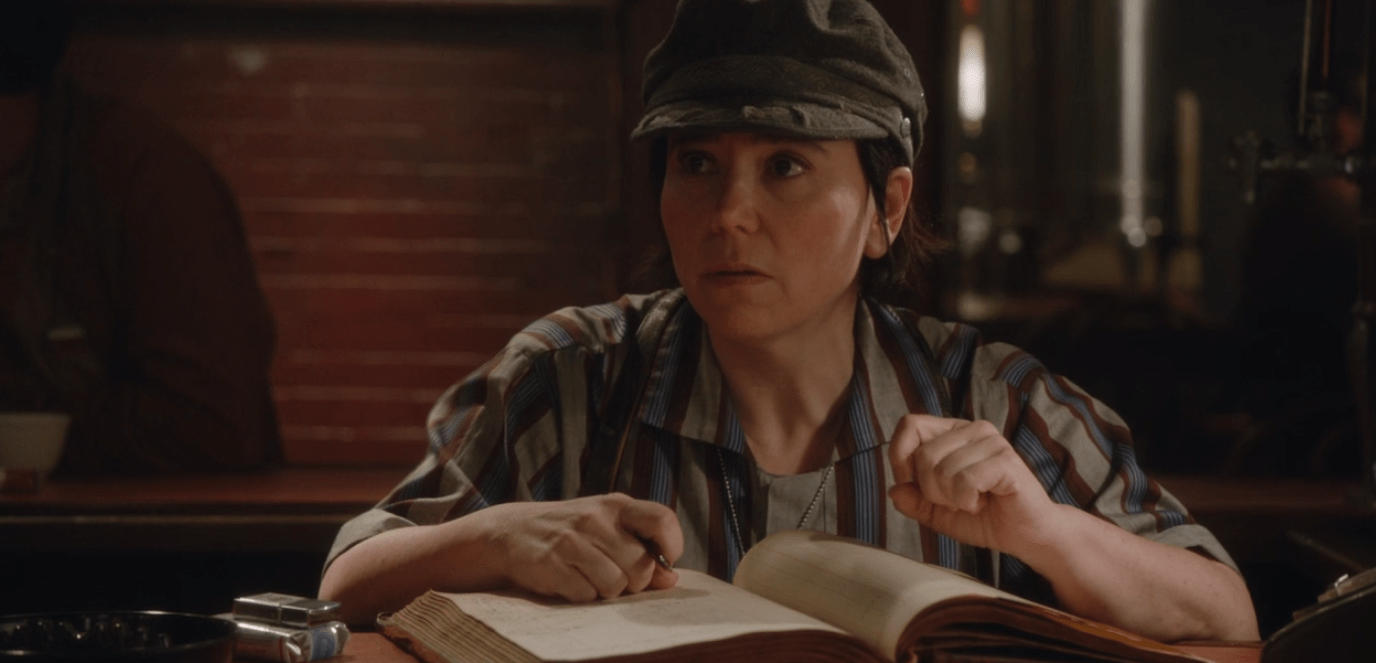

Here is where we find Susie Myerson: a very butch, scrappy, hilarious, endearing, working-class misanthrope in menswear who manages, over the course of two seasons, to embody a love that dare not speak its name or even suggest the existence of its name by never — not once! — encountering another lesbian or lesbian culture, let alone identifying as one. Nor do we sense the subject is being intentionally avoided due to taboos around homosexuality at the time. The overwhelming sense, instead, is that Susie has been neutered. You know, like a house pet.

Do butch straight women exist? Yes! Would a straight woman adopt a butch style in Greenwich Village in the late 1950s? Almost definitely not! If she did, that choice and its accordant contradiction would undoubtedly be a hot topic and could inspire police harassment.

Susie is therefore almost definitely gay, but also not gay. I mean: she’s gaaaaay. But Amy Sherman-Palladino and Dan Palladino talk about Susie like how your parents would talk to your grandparents about you in the actual 1950s.

In Rolling Stone, they wax poetic about Midge and Susie acing the Bechdel Test with their important female friendship while avoiding the meat of the matter. “Susie is a little more mysterious. She’s a woman who basically at some point shut down in her twenties, and even we don’t quite know why—” says Dan.

He’s interrupted by Amy: “Well, I don’t think we don’t know totally. Susie is somebody who, again, did not fit the times. She was not a beauty. Where did Susie fit in with the kind of clothing that she wears and the views that she has?” A few grating clauses later, Amy declares that Susie’s “never gonna find a husband, have some kids” because “that’s just simply not an option.” Why not? Let’s not say! Better to say “not a beauty” than “a lesbian.”

Let’s say this instead: “And once you take that option off the table in 1959, women were left with a lot less choices.”

Dan goes on to note that “once the series came out, everybody was reading into it,” without addressing what, exactly, everybody was “reading into.” He concludes: “That’s our ultimate goal, to get people to read into it what they want to read into it. Make it their own.”

The problem with that assessment is that Susie’s sexuality is the only one requiring a read-into. She’s the only character on Mrs. Maisel who is not, in fact, explicitly heterosexual — everybody else is married, or they’d like to be, or they talk about their wives or husbands or how hot this or that boy or girl is. But not Susie!

If we give the creators the benefit of the doubt — that Susie’s gay, it’s just not discussed because it’s the ’50s and she’s a private person — then why wouldn’t they acknowledge that in interviews and other press around the show, conducted in 2018? And why are we still, in 2018, bending over backwards to give creators the benefit of the doubt?

Bafflingly, in an interview with Cosmo, Alex Borstein said her dream for Susie is for her to “get married and have babies.” What?!

After Season One, we were willing to forgive the Ambiguously Gay trope. There was a lot to set up, after all. The details would come later. Judith Katz, a butch lesbian author who came of age in the ’60s and ’70s, described Susie’s identity as “never spoken but clearly intended” and declares, “Susie Myerson is a butch Jewish dyke as sure as I’m writing this down.” (Unfortunately though, Susie’s character isn’t Jewish.)

The only reference to Susie’s lesbianism in Season One was in the finale, when Susie informs Midge’s husband Joel that he’s “barking up the wrong tree” when he attempts to secure a spot on The Gaslight’s lineup by complimenting her “blouse.”

Then Season Two dropped, unlike any acknowledgement of Susie possessing romantic or sexual desires. “I deeply dislike what they are doing with Susie this season,” tweeted writer Jeanna Kadlec. “I had higher hopes for butch representation on television, ESPECIALLY after Alex Borstein won an Emmy for this role.”

I’ve never been a Gilmore Girls fan, and certainly wasn’t encouraged to give it a shot when, called upon to remark on The Gilmore Girls’ subtextual homosexuality in 2013, Amy declared, “We had characters in the town that we thought of as gay. And we just thought of them as characters.” (She declined to tell the reporter who of these “just characters” were secretly gay.) Apparently, Sookie was initially written as a lesbian, but that idea was nixed by the WB back in 2000. But when Gilmore Girls: A Year In The Life debuted — a decade after the original concluded, in a new, way more accepting milieu — the show still seemed fundamentally uncomfortable with any actual queer representation.

“Midge and Susie, it’s a love story, you know?” Alex told Hollywood Life. “I’m not necessarily saying it’s a lesbian [love story], but it’s a female love story, and [Joel]’s part of that triangle.” I suppose that quote may have encouraged Midge/Susie shippers but if anything, I’m grateful Susie hasn’t fallen into the tired lesbian trope of “poor mannish lesbian crushing on her beautiful straight best friend.” It’s not a love story with Midge I yearn for, but an independent sense of self for Susie. When Susie found herself a family of sorts at Steiner Mountain Resort (including at least one man Susie clocks as gay), I thought her moment for love had finally come. But it was not to be!

Even more unfortunate is how thrilling and historically accurate it’d be to actually call Susie what she is in a show that suffers from chronically low stakes. 1950s-era lesbian liaisons are richly dramatic, which’s why they’ve popped up in other period dramas of the era like Masters of Sex, The Man In The High Castle, Bomb Girls and Call the Midwife.

It was a complicated time to be gay. “Suddenly there were large numbers of women who could become a part of a lesbian subculture,” writes Lillian Faderman of the era, “yet also suddenly there were more reasons than ever for the subculture to stay underground.” Post-World-War-II, homos who’d been dropped off in big cities developed dynamic queer communities. Women had, during the war, been let into the workforce, which supplied economic independence, acceptable venues for girl-on-girl socialization and the freedom to wear pants. Conversely, threatened by the confidence and marketable skills acquired by women during the war, American culture in the ’50s took a hard conservative turn, doubling down on obligating women to get married, have kids and vacuum. Then you’ve got the anti-Communist witch-hunts of the Cold War era and the Lavender Scare, characterized by obsessive suspicion of literally everybody weird. The government was cracking down on the homosexuals, forcing them into the closet or out of work. Even leftists were suspicious of potential gays and lesbians in their midsts. The FBI monitored gay bars, psychologists were publishing dubious studies that painted lesbians as hysterical lunatics in need of treatment, pulp fiction offered refuge as well as villainization and condemnation; and in many places it was still technically illegal for homosexuals to “gather.” In 1958, Barbara Gittings established the New York chapter of the Daughters of Bilitis, a social club dedicated to a “respectable” image of lesbians: white, middle class, wearing skirts, eschewing butch/femme.

When Season Three begins, we’ll be heading into the ’60s, an era of social upheaval, especially for queers in New York. Will we, then, finally acknowledge that Susie is queer?

Listen; there’s a lot to love about The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, and most people do. It’s delightful to experience: smart, cheerful and loaded with charm, funny quips, lite-feminist principles and genuine out-loud laughs. Alex Borstein’s performance is aces. It’s just edgy enough to stimulate your intellect but not too edgy for your Bubbe (although she might wonder why Mrs. Maisel’s butcher sells pork or everybody wishes each other “Happy New Year” (in English!) on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement). Its agenda is subtle and easy to swallow, like a wee matzo ball. But it’s also a bit of a neoliberal fantasyland where anti-Semitism doesn’t exist, and sexism only exists to be delightfully skewered.

In 2018, subtext, the life raft we once clung to, has been sent to sea and in this new bold era, Susie’s squelched sexuality somehow feels personally insulting. (Worth noting that Amazon also cancelled two series with actual butch lesbians playing butch lesbians this year, I Love Dick and One Mississippi.) I get itchy hearing people talk about the show, like how I used to feel when straight people talked about Elliot Page allegedly dating Alexander Skarsgård before Elliot came out in 2014. It seems to represent a fundamental unease with queer stories, wanting all the benefits of a sassy gay sidekick without the hard work of acknowledging, let alone understanding, their multifaceted personhood. Put that on your plate and you’ll really have a story to dine out on.