Anime Amazons

Probably my favorite panel of the entire convention, “Anime Amazons” was hosted by Kristiina Korpus, Kim Grzesik and Carly Smith and focused on the portrayal of “strong female characters” in anime, manga and (mostly Japanese) video games. They had a fairly expansive definition of “Amazon” – not just stereotypical female superheroes and gun-or-sword-slinging “badasses”, but just about any woman who was fighting for something.

They began by talking about the obvious example: magical girl series such as the aforementioned three, Sailor Moon and Cardcaptor Sakura. Their characters are generally pointed out as excellent role models for girls, and have influenced even Western girls’ cartoons, such as The Powerpuff Girls and the latest incarnation of the My Little Pony series, Friendship is Magic. Yet, the panelists pointed out that even some of these have limits. In the early episodes of Sailor Moon, heroine Usagi Tsukino had a tendency to be a damsel-in-distress to her love interest, Tuxedo Mask. Of course, by the end of the first season, that dynamic was very much reversed and would remain there, with Mamoru becoming a favorite whipping boy for each season’s Big Bad. But still, even Sailor Moon had places to improve, for playing into that stereotype initially.

Unsurprisingly, most of the series where they pointed out awesome female characters were those aimed at women – shojo or josei (the older version of shojo, anime focused on young adult women). It’s no surprise that media aimed at girls is generally going to try harder to represent women positively. Yet, the panelists made sure to examine anime aimed at men or boys, like shonen, and show how it was often better than we expected, but still left a lot to be desired.

In this section, they did an in-depth look at the female characters of one of the most popular shonen series of the past decade, Fullmetal Alchemist. This was fascinating to me since I love FMA; the first of its two anime series is my favorite anime ever. The franchise is one that also seems to get a lot of praise in fannish circles for how it treats its women, but I always felt like it majorly missed the mark in that regard, and the “Anime Amazons” panel helped me better articulate why.

On the plus side, the show’s female characters are well-developed, often showing a blending of “masculine” and “feminine” traits – like real women. For example, Winry Rockbell, the protagonist’s best friend and love interest, is girly and enjoys domestic tasks like baking, but her main goal in life is to become an accomplished mechanic, and she obsesses over fancy tools and the like. The series is also not too big on gratuitous fanservice or male-gaze pandering, and what it does have in that regard, it more than matches with shirtless scenes for its muscular men. The author of the FMA manga, Hiromu Arakawa, is a woman, and that shows in how she writes women.

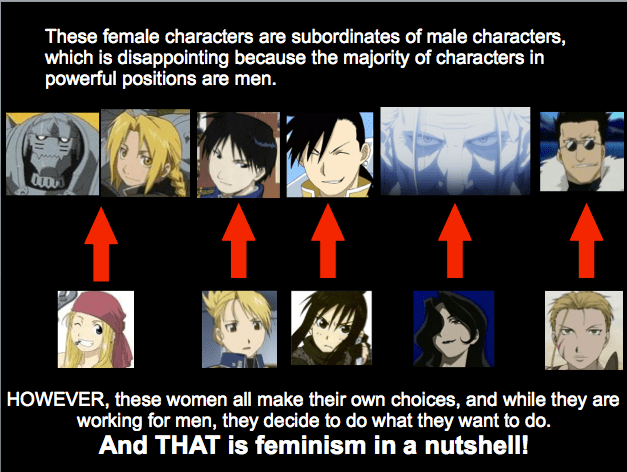

However, even if FMA’s women are better-developed than a lot of shonen girls, they still are largely defined by their male love interests. For example, Lieutenant Riza Hawkeye, a badass gunslinger and war veteran, is still defined largely around her commanding officer and implied love interest, Roy Mustang, serving as his bodyguard and as support to his goal to reform the country; she outright says she couldn’t live without him. And while there’s plenty of focus on Winry’s career and her personal struggles, she is, as the panelists put it, mainly there to provide someone for the male protagonists to come home to when their battles end. There are at least two older ladies, powerful alchemist and housewife Izumi Curtis and fierce military commander Olivier Armstrong, who are excellent exceptions. But overall, there’s a very patriarchal pattern to how the women of FMA are written, as the panelists pointed out:

This brings me to one of the few places where I disagreed with the panelists: the issue of choice. Their conclusion was, because these characters chose to follow men, FMA ultimately wasn’t sexist. However, while I agree that “choice” is an important part of feminism when it comes to real-life women (though, it shouldn’t mean we don’t examine how societal gender programming influences said choices), it doesn’t quite apply to fictional characters, who literally don’t have agency – their choices are determined by their writers. Ultimately, it’s very easy for an author (like Twilight author Stephenie Meyer, who also uses this defense for her own books) to give his or her female characters a pattern of choices that are in line with restrictive gender expectations and that define them around men, by making it as though it’s the female character who wants them that way. And when it’s a pattern, as it is in FMA, it can suggest troubling things about “what women want.”

Even within the shonen genre, though, the panelists mentioned that there were other titles where women had greater presence. The anime Soul Eater, for example, includes a powerful girl as main character as well as a strong female antagonist, something relatively rare in male-centered anime, especially in a form where her character doesn’t imply hateful things about women as a class. Another example, Claymore, has women filling nearly the entire cast, in roles where the boys would usually be, and the men are in the sideline, “useless” roles.

At this point, the conversation largely shifted to video games, a topic where I’m less well-versed. But one thing that one could easily take away is that women’s presence in games has improved over the decades. They mentioned the Tomb Raider games as ones where, while perhaps not all that progressive in how they catered to the male gaze, set a precedent that men would play games with female protagonists. They also mentioned franchises like Pokémon which have made more room for women as time goes on, such as adding the option of playing as a female character in 2001. And now we’re getting more games that are actually aimed at women, or at least acknowledge that women who want strong-yet-relatable versions of themselves in games are a market. Video game culture is still very sexist, but they revealed with their examples that the games themselves have often given us some well-rounded and capable female characters.

Overall, the takeaway that was there are a lot of ways to be an “Amazon.” The panelists didn’t just talk about good-vs.-evil stories, but even more slice-of-life ones like Nana that had fantastic women in them. As they said at the end, what makes a female character an “Amazon” is not how she fights, but what she’s fighting for.

What’s great about anime and other fan conventions that are as large as Otakon, is you can find whatever niche you want among its myriad panels, workshops and other activities. If you want an autograph from a famous voice actor, to learn how to improve your cosplay, or simply to blow lots of cash in the dealer’s room, there’s a place for you. But there’s also a place for difficult conversations about women and their representation in anime, from various perspectives. And that continues to be the most rewarding part to me, year after year.