Today, most people in the United States are celebrating Columbus Day. They get a day off of work or school, rejoice at their local mattress store sale, and a lucky few get to claim the holiday for its “original purpose” — the celebration of Italian-Americans. A few cities, including Seattle, Berkeley, and Minneapolis, the newest place I call home, do not recognize Columbus Day and instead celebrate Indigenous Peoples’ Day. Just this past week eight more cities have announced they’re joining that push. As folks flock to department store sales and many more to parades honoring the man, the legend, and symbol of settler colonialism, Indigenous people from across Turtle Island come together to commemorate Native cultures. Like most days throughout the year, today we dance, sing, eat, laugh, and Indigenize social media together. Today, however, we do so with a special purpose: to reclaim and redefine a holiday intended to celebrate the genocide and forced assimilation of Native peoples. By protesting, healing, and sharing together we celebrate not just the diversity of our histories and cultures but our continual survivance — a term coined by scholar of Native American Studies, Gerald Vizenor, meant to name the active presence of Native survival and resistance. Native survivance rejects the myth of the vanishing or the dying or the already assimilated Indian. It insists that our people have endured five centuries of settler colonialism and continue to thrive through our languages, cultures, and ability to love, laugh and live amidst hardship.

Survivance, for me, also means the celebration of our Native LGBTQ and two-spirit community. Since Columbus and his people first arrived on Native lands, the regulation of Western sexual and gender norms has been one of the most prominent modes of colonization. Traditionally, many Native cultures had and have more than two genders and in some communities, queer/two spirit people were highly revered. Unfortunately, forcible assimilation of Native peoples included the imposition of heteronormativity and with it discrimination against trans and queer members of our communities.

While many tribes legalized same-sex marriage prior to this year’s United States Supreme Court ruling — including the Coquille Tribe in Oregon, the first to do so in 2009 — parts of Indian Country still do not recognize same-sex marriage. More importantly, too many Native queer and trans youth face school bullying, homelessness, and high rates of suicide. Yet, queer and trans Natives survive, resist, and thrive every day. The Bay Area American Indian Two-Spirit (BAAITS) collective throws an incredible two-spirit powwow every February in San Francisco. We have a gay Native woman, Susan Allen, on the Minnesota legislature and other queer Native folks doing vital work in the public and private sectors in all 50 states and 562 federally recognized tribes. Many more of us are simply going about the daily work of revitalizing our Indigenous languages, creating art and transformative justice, and dating, marrying and loving whom we choose. On Indigenous Peoples’ Day we celebrate our queer survivance — nothing less than a fantastic feat given the myriad of ways the narratives of settler colonialism, popular culture, and governments have continually told us we should not, do not and cannot exist.

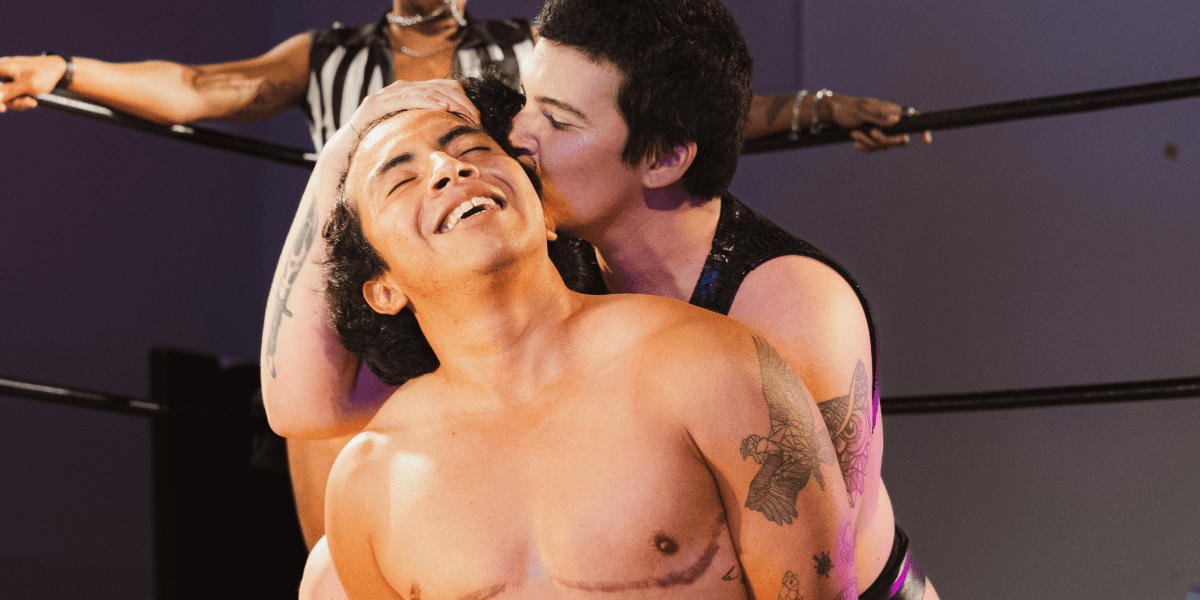

Like many queer Native folks, I celebrate Indigenous Peoples’ Day by, yes, surviving the historical and ongoing injustices of racism, colonialism, and patriarchy but also by just simply living a more critical and loving life. I celebrate by marching alongside the Native community of the Twin Cities and those in solidarity with us in resistance to Columbus or “Discovery” days, learning my language, Ojibwemowin, and showing up for Native women and children at the legal non-profit I work at. Because Native and queer survivance is as much about love as it is resistance and culture I also call my mom and grandmother to say “I love you.” Finally, I go on an adventure date with that cute girl from my neighborhood because while sometimes queer survivance looks like protests and ceremony other times it’s hand-holding and sweet kisses. Our survivance doesn’t look like any one monolithic activity, and neither does our community; today and every other day, we survive and thrive in a thousand different ways.

Comments

This comment has been removed as it is in violation of Autostraddle’s Comment Policy. Repeat or egregious offenders will be banned..

The idea that Columbus was of Jewish origin (and that his voyages were actually financed by wealthy Jewish financiers) has been around for a long time (just like the theories that he was really Catalan or Portuguese or secret royalty), but as far as I know — having read quite a bit about it — there’s no direct evidence for it, only some rather strained circumstantial evidence. It’s basically on a level with the theory that Francis Bacon wrote Shakespeare’s plays. Even though Columbus’s DNA has actually been analyzed from his bones, with no evidence of any Jewish origin (compared to the Y-DNA and mitochondrial DNA of Sephardic Jews), the Jewish origin theory has gotten a lot of publicity in recent years, because a linguist at Georgetown (not a historian) has popularized it, and then of course the press likes to repeat it as fact. Although it’s not usually as transparent an effort as yours to “pass the blame” to the Jews for Columbus’s wrongdoing. (“Messianic Jew,” by the way, is a ridiculous anachronism; nobody used such terms in the 15th century.)

So please stop it. It’s not what anyone needs (let alone Jewish people!), and even if it were true, it’s really a derail from the point of the post.

No one is “blaming” Jewish people for the genocide of Native Americans. Much of the debate surrounding Columbus’ identity emerges from the Jewish community, itself, not from the popular media, as you suggest.

Secondly, to identify one individual as the cause of centuries worth of genocide is to obfuscate history; as inaccurate as claiming that Hitler, was singularly responsible for the systemic horrors of Holocaust. If Columbus had not “landed” in the America’s, someone else would have. To place an Italian face on the genocide of Native American peoples removes the blame from those who committed the atrocities. President George Washington led a “civilization” campaign to force Christianity and the English language on various native tribes. President Andrew Jackson, while serving as a general, slaughtered thousands in the process of land-grabbing. President Martin Van Buren was responsible for the Trail of Tears. The list goes on. None of these individuals were Italian, and each acted of their own volition and self-interest.

Italian Americans were lynched in the American south because of racism. They were subjected to Jim Crowe laws. They were forced to sign their children away to the orphan trains. They were relegated to dilapidated slums and indentured servitude in northern American cities. They bore the brunt of anti-immigration sentiment leading up to and during the Great Depression, and many were forced to change their names and give up their native language and culture to be considered “white” on paper. I agree that Columbus day should be abolished–because we as a people should not be hinging the validity of our citizenship on a false narrative, nor should our value as a people be based on others’ perception of our whiteness.

Nobody was condemning all Italians or Italian-Americans because of Columbus. So there’s no need to recite a litany of discrimination against Italian-Americans. You’re playing Oppression Olympics.

And the Trail of Tears was under Andrew Jackson, not Martin van Buren.

Taylor, thank you, thank you, for writing and sharing this.

Yours in love and solidarity.

This was so lovely and strong.

Couldn’t have put it better myself.

Thank you for your personal and historical insights Taylor. As a lifelong Minnesotan, it was especially intriguing. I didn’t even know we had a gay native women on our legislator. I first read this the day it was posted and was deeply moved. No was had posted yet and I wasn’t sure if I should be the first. Given the idiotic and divergent first response you got, I guess maybe I should have.

Well better late than never. Congratulations on a great first article and keep on spreading the love.

Thank you for this – joy and power to you!

I wanted to share some of the amazing Native surviving living thriving from K’emk’emlay/ Vancouver –

I pass this incredible 60 foot Eagle Staff every day – part of the Culture Saves Lives response/ movement : http://www.straight.com/arts/530606/20-stunning-photos-show-power-culture-saves-lives-powwow-downtown-eastside

Other snippets – the beautiful cedar hats that I am seeing more frequently being proudly worn. The lady who has created the button blanket for her loved dog. The lady beading an intricate Canucks brooch on the bus.

I send love to all of you <3 <3 <3.

thank you ever so much for this article !!

love and solidarity

thank you so much for writing this! I love this idea of “survivance” and I’m excited to read Vizenor’s work and get some more info on the discourse around this concept