I recently heard CeCe McDonald speak, and the youngest person in the room stood to ask a question. This small human was probably nine or ten, and asked CeCe what other transgender women she looked up to. CeCe named Janet Mock and Marsha P. Johnson, among others, and the moment elicited a collective awwwww from the several hundred people in the room. I thought about how important it is for young humans to learn about the leaders in our multi-faceted struggle for justice.

On the 45th anniversary of Stonewall and the 50th anniversary of the Civil Rights Act, it’s worth interrogating how we learn and know our histories. For many of us, our time in school is foundational in how we see the world and ourselves. In school we have histories and literature delivered to us, and whether or not we saw ourselves in those histories or books impacts us. But along with the concrete material presented to us, we also inevitably absorb how we are treated by our teachers, peers and other school staff. School is a social experience. It’s where we learn where we fit — or don’t.

There have been various calls in recent years for LGBTQ representation in our textbooks. A 2009 study by GLSEN suggested that including LGBTQ people and history in classrooms helps make schools safer places for LGBTQ kids. This type of curricular inclusion validates young LGBTQ people’s identities and promotes our history as important and significant to the current state of things. But just putting some events — Stonewall, the overturning of Prop 8, etc. — in our books is far from enough. To keep it so simple would make it too easy to write the history of LGBTQ struggle as on its home stretch toward a finish line of marriage equality and workplace nondiscrimination laws for all, when there is still so much left to be done on the front of mass incarceration, police brutality, homelessness, unemployment, poverty, discrimination and violence that queer and trans people face every day. In order to include a history that is both relevant and empowering for LGBQ and T populations, textbooks need to accurately represent our history and the struggles that remain. For example, effective and inclusive historical representations of Stonewall would talk about the role that trans women played in the riots, and would discuss how trans women were later pushed out of the Gay Liberation Front so the cis people in the organization could be more easily accepted by a mainstream American population.

That being said, it’s important to acknowledge that it’s not like American history curriculums are doing a wonderful and comprehensive analysis of other marginalized groups’ histories and has just unfortunately left out LGBTQ people. There are so many ways that social movements and histories of struggle have been poorly represented in American schools that teach a white-dominant, male-dominant, heteronormative and imperialist narrative of American history. If you took American history — and if you even got to the Civil Rights Movement after the long chronological slog through a detailed history of every war the U.S. ever fought — it’s likely you learned about Rosa Parks as a lady who wanted to rest her feet while taking the bus home from work, so she sat down in an open seat in a spot reserved for white people, was arrested, and then suddenly there was a yearlong bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama. What you probably didn’t learn is that Parks was an activist who had been organizing to fight sexual violence against black women for many years prior to the riots, and that it was largely because of the community networks created by anti-sexual violence organizers that the bus boycotts could be so successful.

This nearly-forgotten history (which you can read about in Danielle McGuire’s very excellent book, At the Dark End of the Street) gives insight into the intersections between women’s struggle and the struggle for civil rights. It also challenges white-dominant narratives of feminism that have white women inventing the fight against sexual violence, and male-dominant narratives of the Civil Rights Movement that relegate women to insignificant roles.

The way the entire Civil Rights Movement is depicted in U.S. history books shows a tendency to package struggle into a neat narrative that allows the Civil Rights Movement to be depicted as a relic of the past, rather than one that continues to be relevant today, as the Supreme Court hands down decisions that would infringe mostly on the rights of women of color, and black and brown bodies continue to be criminalized and marginalized. History books don’t have to ask for a continuing interrogation of injustice in American society if they depoliticize the politics of past struggles. Another significant example of how struggle and violence are written out of mainstream American narrative is all the talk of “Manifest Destiny” in US history textbooks. Traditional lessons on Manifest Destiny mask its history of genocide and colonization of native peoples by portraying it as a harmless great America-expander.

If it sounds like these kinds of lessons would take a lot of time — they would. And we could talk about the shortcomings of American history textbooks probably forever, but another factor in limiting the kind of things kids learn about in school is the state of education in the US. We are not exactly at an easy moment in American education to be creating a more elaborative and critical curriculum. The push by corporate entities and administrators for education reform has been heavily opposed by teachers and students, but is, nonetheless, happening. These reforms, like the implementation of the national Common Core Standards, put increased emphasis on high stakes testing, both in measuring student achievement and teachers’ performance, which means more instructional time has been dedicated to test prep and test-taking, pretty much across the board.

Kathy Kremins, who has spent 33 years as a public high school educator, noted some of her concerns with Common Core: “[Common Core] maximizes ‘informational texts’ and minimizes poetry… ignores graphic works and YA literature; it strongly advises against creative analysis and activities.” And most teachers don’t have the 33 years’ experience Kremins has. Increased pressure and workloads on teachers as a result of the emphasis on test scores and other reforms imposed by administrators has led to poor working conditions for teachers and incredibly high teacher turnover, which means that teachers don’t have time to refine their skills and tailor their curriculum to address their students’ needs.

Public school teachers who have tried to include history and perspectives of historically marginalized groups, including LGBTQ perspectives, have been suppressed, despite all signs that indicated their positive impact on the grades and lives of their students. The Ethnic Studies programs in Tucson, Arizona were targeted by the city school board and then made illegal by state law; and more recently on the college level we saw South Carolina create their bizarre penalty system for universities who taught LGBTQ curricula.

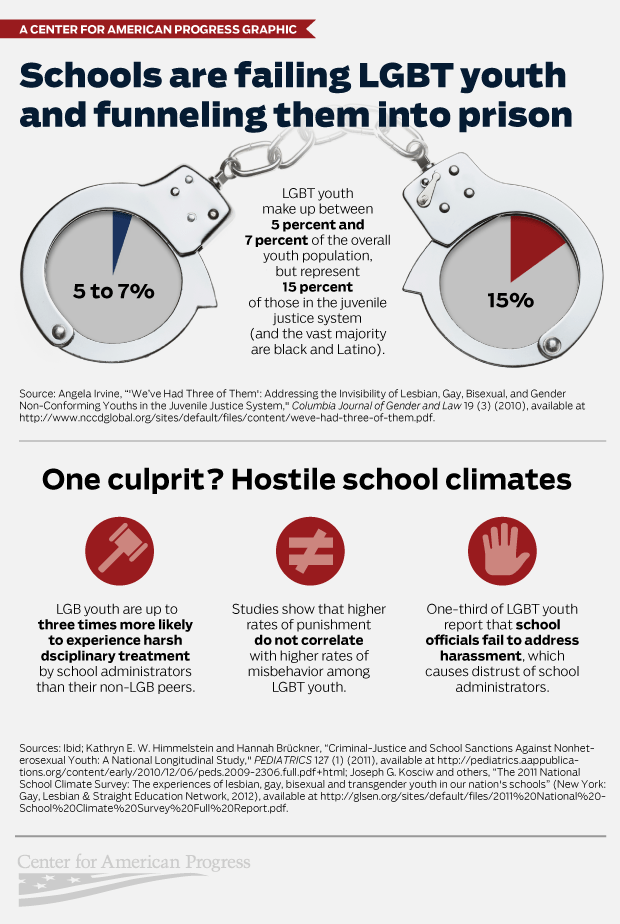

Also, it doesn’t matter much what’s in the curriculum if students are being criminalized in the classroom. The growth of the school-to-prison pipeline has disproportionately targeted black and Latin@ LGBTQ students. Validation or safety that could be nurtured by the inclusion of LGBTQ narratives in a curriculum can’t cancel out the negative impact of fear and antagonism created by a heavily policed environment on a student’s ability to learn and thrive.

We can hope for a world where the young people who don’t get to talk to CeCe McDonald in person will learn her name, and the names of other people who inspired her and other people who have struggled for justice, but ultimately a lot more needs to happen across the entire educational system for ALL kids to have safe, inclusive and empowering experiences in school. The impact of high-stakes testing, the school-to-prison pipeline, pressure on teachers and other shifts in the educational system impact our community and youth in ways that we will continue to feel far into the future.