“Remember me as a revolutionary communist.”

These were the last words of Leslie Feinberg, as reported in an obituary by Feinberg’s partner of 22 years, activist and poet Minnie Bruce Pratt. According to the obituary:

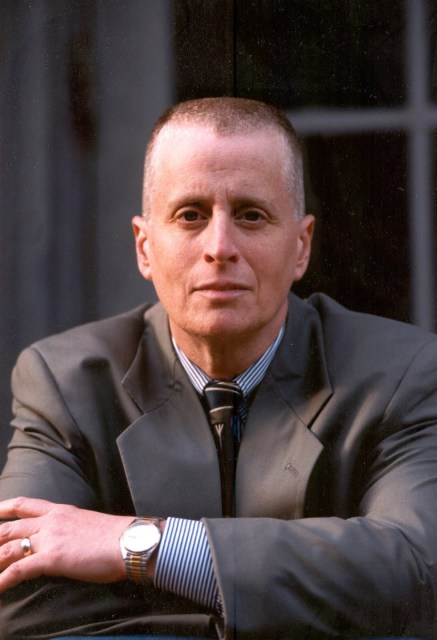

Leslie Feinberg, who identified as an anti-racist white, working-class, secular Jewish, transgender, lesbian, female, revolutionary communist, died on November 15. She succumbed to complications from multiple tick-borne co-infections, including Lyme disease, babeisiosis, and protomyxzoa rheumatica, after decades of illness.

She died at home in Syracuse, NY, with her partner and spouse of 22 years, Minnie Bruce Pratt, at her side.

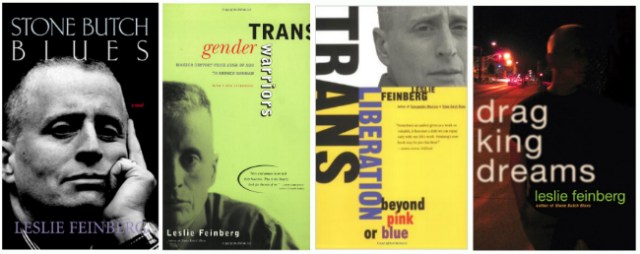

Feinberg’s written work is widely known. Hir groundbreaking 1993 novel, Stone Butch Blues, broke open the discussion about the complexity and fluidity of gender. Over twenty years later, it is still being printed, read, passed around between friends and lovers. For many baby butches and transgender bois and genderqueer lesbians, this is the book that was dogeared and read and reread. Stone Butch Blues has been distributed all over the world, translated into seven languages, and sold by the hundreds of thousands.

The first Feinberg book I picked up was Trans Liberation: Beyond Pink or Blue. My partner and I also own and have read her other books, Transgender Warriors: Making History and Feinberg’s second novel, Drag King Dreams. In 2004, as college students running the campuses feminist organization and pride organization, my partner and I both met Feinberg when we brought her to speak at our campus. Feinberg’s talk was on hir theory of transgender liberation, a Marxist and intersectional view of organizing for collective equity. As Feinberg writes in Trans Liberation, “A political movement isn’t just our physical motion into the streets, it’s the motion of our consciousness soaring, too.”

Feinberg came from a working-class Jewish family, born in Kansas City, Missouri and raised in Buffalo, NY. Held up in academia as a theorist and activist, ze identified with working-class people more than ivory towers. Feinberg began supporting hirself at the age of 14. Due to discrimination based on hir gender identity and expression, ze was unable to get steady work for most of hir life. Ze worked in a pipe factory, cleaning ship cargo holds, as a dishwasher, and other low-wage jobs.

Feinberg was a lifelong member of the Workers World Party, which ze joined in her early 20’s through the Buffalo branch. Over the years, Feinberg was instrumental in many radical mass organizing campaigns. Pratt shares some of this work with the WWP in the obituary:

After moving to New York City, she participated in numerous mass organizing campaigns by the Party over the years, including many anti-war, pro-labor rallies. In 1983-1984 she embarked on a national tour about AIDS as a denied epidemic. She was a key organizer in the December 1974 March Against Racism in Boston, a campaign against white supremacist attacks on African-American adults and schoolchildren in the city. Feinberg led a group of ten lesbian-identified people, including several from South Boston, on an all-night “paste up” of South Boston, covering every visible racist epithet.

Feinberg was one of the organizers of the 1988 mobilization in Atlanta that re-routed the white supremacist Ku Klux Klan as they tried to march down Martin Luther King, Jr. Ave., on MLK Day. When anti-abortion groups descended on Buffalo in 1992 and again in 1998-1999 with the murder there of Dr. Barnard Slepian, Feinberg returned to work with Buffalo United for Choice and its Rainbow Peacekeepers, which organized community self-defense for local LGBTQ+ bars and clubs as well as the women’s clinic.

Feinberg was a gender revolutionary in openly straddling the space between, or rather off of, the binary. In a 2006 interview with Kansas City LGBT magazine, Camp, Feinberg said, “For me, pronouns are always placed within context. I am female-bodied, I am a butch lesbian, a transgender lesbian — referring to me as she/her is appropriate, particularly in a non-trans setting in which referring to me as he would appear to resolve the social contradiction between my birth sex and gender expression and render my transgender expression invisible. I like the gender neutral pronoun ze/hir because it makes it impossible to hold on to gender/sex/sexuality assumptions about a person you’re about to meet or you’ve just met.”

Pratt included these words on pronouns in Feinberg’s obituary:

[Feinberg] said she had “never been in search of a common umbrella identity, or even an umbrella term, that brings together people of oppressed sexes, gender expressions, and sexualities” and… believed in the right of self-determination of oppressed individuals, communities, groups, and nations. She preferred to use the pronouns she/zie and her/hir for herself, but also said: “I care which pronoun is used, but people have been disrespectful to me with the right pronoun and respectful with the wrong one. It matters whether someone is using the pronoun as a bigot, or if they are trying to demonstrate respect.

Diagnosed with Lyme disease in 2008, Feinberg stayed active in organizing, politics, and art. Ze lived her last years in the Hawley-Green neighborhood of Syracuse, NY with Pratt. (Pratt teaches at Syracuse University.) Some of my Syracuse friends met Feinberg when ze came to a community meeting about starting a Syracuse LGBTQ community center, something the city is sorely lacking. Feinberg was instrumental in raising awareness and support for CeCe McDonald. Ze was collecting documentation of the grassroots organizing work to Free CeCe in a project called, “This is What Solidarity Looks Like,” meant to be part of the free-access version of Stone Butch Blues ze was planning to release online for the book’s 20th anniversary.

Feinberg took up photography as a hobby when ze could no longer read, write, or talk. Hir work is posted on Flickr, including a “disability-art class-conscious documentary of her neighborhood photographed entirely from behind the windows of her apartment.” Hir photography was also shown at the Syracuse gallery, ArtRage.

Feinberg blogged about hir experience with Lyme disease and health care access as a transgender person in her “Casualty of an Undeclared War” series. Feinberg’s friends are working to post hir final works of writing and art online at a new site, LeslieFeinberg.net.

Feinberg is survived by Pratt and an extended family of choice, as well as many friends, activists, and comrades around the world in struggle against oppression and for liberation.