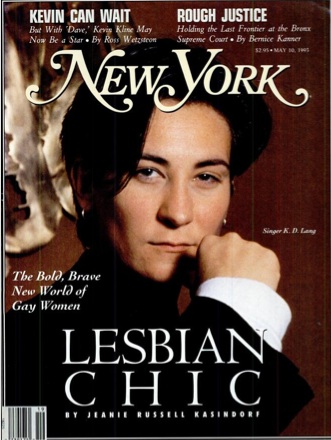

Feature image via New York Magazine

Style.com recently brought the queer internet to a screeching halt with a short piece offensively titled, “IS LESBIAN CHIC HERE TO STAY?” that began, “Lesbians! They’re everywhere.” The article claims that fashion is feeling the effects of an alleged recent spike in “high-vis lady love,” and cites examples like “girls running around in Air Jordans and baseball caps.”

Maybe the piece is meant to be tongue-in-cheek; maybe the writer knows it’s silly to equate combat boots with lesbianism and was subtly trying to mock those who do. Unfortunately, I doubt it.

Visibility, no matter how you spin it, is an extremely complicated issue. We need to be able to identify each other in order to form relationships and communities, and sometimes we feel the need for people outside of our community to be able to identify us as well. But what we don’t need is for people outside of our communities to define what makes a lesbian visible, to pick a certain gender identity they feel comfortable with and declare it “chic” and “hip” and then not only police our genders based on that ideal, but also appropriate it. Because the Style.com article isn’t just talking about lesbians being chic; it’s talking about how straight women are employing trendy lesbian signifiers as the newest hippest accessories.

And that’s a real thing — Miley Cyrus’s new haircut does make her look like a baby dyke, and here in NYC, it’s becoming increasingly impossible to tell the hipsters from the lesbians. Septum piercings, carabiner key chains clipped to belt loops, undercuts, and all the other things that one used to be able to rely on to identify queers who don’t fit otherwise fit into traditional lesbian gender categories are now just the latest greatest way to show how cool you are, for anyone. The Gap sells “Sexy Boyfriend Jeans,” menswear-inspired pants that are on-trend in that they acknowledge the desirability of androgyny branded in way that isn’t too butch to be hip. Goddess forbid The Gap make masculine jeans for female bodies without mentioning men in the branding.

But all this isn’t really news, is it? Fashion’s love affair with lesbian-inspired androgyny isn’t unique to the runways of Fall 2012. In fact, the mainstream’s fascination with the style known as lesbian-chic is cyclical.

As Riese and Alex noted back in 2009,”The term “Lesbian Chic” has been tossed around with relative abandon since 1993, when it was first popularly employed in response to heterosexual supermodel Cindy Crawford straddling lesbian k.d. lang on the cover of Vanity Fair.” For example, New York Magazine published an article called “Lesbian Chic” in 1993 that said, “There have always been glamorous lesbians… but the short-haired ‘bull dyke’ is still many Americans’ idea of what a gay woman looks like. Now the ‘lipstick lesbians’ and ‘designer dykes’ share the bar with the ‘butch/femme’ group; the downtown black leather crowd and women in Jones New York suits wander among them.”

The year 1993 represented a shift in attitude, both from within and from outside of the lesbian community. A new generation was becoming visible to mainstream America, one that turned its nose up at butch/femme relationships and declared androgynous glamor as the sexiest way to be a lesbian. The New York Magazine article interviewed a smattering of lesbians, one of whom actually equated bull dykes with sleaziness, thus privileging the sexuality of those who embodied “lesbian chic.” Though the article says, “In the nineties, it seems, there is room for every style,” it also seems to be saying that the best style is that of the “designer dykes,” which, incidentally, seems to be the easiest lesbian aesthetic for the mainstream to digest.

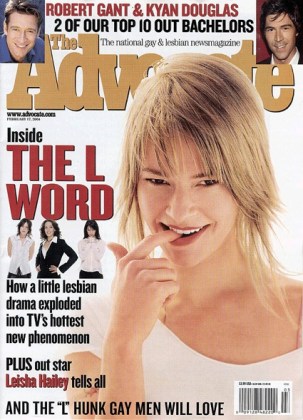

Lesbian chic reappeared in 2004 with the debut of The L Word. That year, The Advocate published “Lesbian chic, part deux”in which lesbian writer Kate Nielsen describes the allure of “The postmodern lesbian: not totally butch and not totally lipstick chic but definitely demographically desirable.” Nielson identifies The L Word as a way for television to harness that special power of lesbian chic by featuring slender, glamorous actresses with alternative lifestyle haircuts having beautifully choreographed sex scenes that are just tame enough to be palatable to mainstream viewers. She acknowledges the fascination with lesbian chic from the previous decade, saying, “Haven’t we been through this already? Yes, we have. But that was then, this is now. We have to remind people how cool we are if they’re not actually hanging out with us. You know, out of sight, out of mind — “don’t ask, don’t tell.”

Not everyone saw it as a reminder of how cool lesbians are — for many, this seemed to be the first time they were hearing it at all. Guy Trebay, a man, published an article in The New York Times that same year saying that The L Word “showed that — far from being frumps doomed to Manolo Blahnik deficiency — lesbians are a powerful presence in fashion, in both predictable and unexpected ways. The old stereotypes have not faded. But they have slipped into something decidedly cool.” This point of view represents a steadfast popular opinion that the old stereotype of lesbians — read: butch — isn’t cool.

Since the debut of The L Word, lesbian signifiers have slowly and steadily made their way into mainstream fashion. But it’s still this very highly-policed, very appropriate way of being a lesbian that wins a nod from fashion. The cast of The Real L Word doesn’t look all that much different from its predecessor, right down to the obsession with tall, skinny eyeliner-wearing futches.

So while the lesbian chic obsession is a form of heightened visibility, it also serves to erase other, equally valid ways of being a gay woman. The Style.com article that brought lesbian chic back to our attention was only talking about the lesbians whose style is palatable for high fashion. And just like the reflections on lesbian chic in decades past, it re-defines and re-packages lesbianism as that which is indicated by a certain style. It also describes lesbian chic as a trend that has recently been invented, and seems to be likewise saying that lesbians have only recently been discovered. If we’re not making waves with a hipness that is sexually appealing to all demographics, regardless of our actual sexual availability or interest, it seems we aren’t noticed at all.

But honestly, I don’t think this is all negative. It is certainly easier than it used to be to buy clothes that fit my own gender identity, which is somewhere in between femme and androgynous. I actually really like The Gap’s “Sexy Boyfriend Jeans” (I just can’t afford them). And lesbian designer Alicia Hardesty can launch her super awesome clothing line “Original Tomboy” and count on fashionistas of all gender expressions to appreciate the dykey aesthetic of clothes that re-define what it means to “dress like a girl.”

It’s important, though, to not let mainstream ideas of what a lesbian should look like influence our ways of identifying each other. It’s great that a specific kind of lesbian can enjoy applause from high fashion, but the rest of us have valid ways of showing our sexualities, too. Let’s not forget about the beautiful “bull dykes” just because fashion wants us to, and let’s not forget that femmes are just as gay as a dyke in skinny jeans and a leather jacket. We can appreciate that lesbian chic is back in vogue, but let’s not abandon those whom “chic” does not include.

Comments

Very tired of parsing all these different labels for lesbians. I’m a lesbian, is that not enough? Do I have to decide where my outfits lie on the spectrum as well? I think all these fashion related labels are exclusionary. I feel a bit lost among the soft butches and tomboy femmes and chapsticks and high femmes and bull dykes and all these other things that all seem to come down to clothes and hair. Underneath it all we’re just women and we’re STILL defining ourselves by our appearance.

I agree, sort of, in that there are too many words and it’s baffling and they can come across as tiny boxes to pigeonhole people in, but I think they only define you if you let them. I identify as chapstick femme when I need to talk about style because in one handy two-word package it conveys that I probably wear Sperrys most of the time and get hives from pink zebra stripe anything, but in any other context I use other vocabulary.

Exactly. I spent ages last week thinking about how in my own head at least, I call myself a “low maintenance femme”. and then getting annoying with myself for thinking I even have to think of a suitable phrase, I mean when and where do we really need to use these terms? The only other people I know who feel the need to label themselves so strongly are teenagers with their goths and emos and whatnot. Aren’t we past that, as grown women? I don’t want to identify what “kind” of lesbian I am by my hair cut. And in a way I suppose the main streaming of “lesbian chic” helps with that, because those kind of things cease to be an indicator.

I actually identify really strongly with femme. I don’t feel like it’s an annoying phrase or something that I’m shoved into at all. I also don’t feel like it’s a way of just being able to talk about fashion with other people at all. I feel like femme is an integral part of my identity, just as important as gay. And to be honest I probably get about as much shit for being femme as I do for being gay. I feel like femme is an identity that I need to label BECAUSE of the fact that it’s something about me that is targeted. And I find it empowering to be able to put a name to that identity. I probably even identify more strongly with being femme than I do with being a woman.

Whew. I’m almost glad I live in a conservative part of the South on a conservative, sorority-dominated campus where people dress very traditionally vis a vis gender. If I see a chick wandering around with an alternative lifestyle haircut, she probably didn’t get it for shiggles, she’s saying something with it, because she’s opening herself up to being judged as “That Dyke” by everyone around her. I mean, downside, dyke=slur here, but my already shaky gaydar is relieved.

But yeah, as a chapstick femme,I’m severely less than thrilled with how this emphasizes that if you haven’t lopped your hair off and invested in studded leather you aren’t a real lezzer. Great article!

I don’t know. I’ve reached a point in my life where I just feel like moving to an island with all the other gay girls because I am so sick of straight media and everything. I just want to tell all these magazines and tv shows to just shut up. I do not care about anything you have to say. I don’t want to know what you think about me.

And I know thats bad and I’m supposed to be about EDUCATING people and CHANGING THINGS and so on but dear lord, why are they all so stupid and annoying?

This island sounds very intriguing.

it is a camp.

isle of lesbos?

No one owns a trend, a style, a type of clothing or hair cut. Sure, we separate ourselves into various tribes because we want to identify, we want to say “this is me, this is what I am,” and those styles have been appropriated by mainstream fashion and advertising for decades now. It’s not unique to ‘lesbian chic’ but sure, it’s just as annoying. Regardless, as long as we don’t start dictating who is allowed to wear what, and as long as we keep away from that dangerous ‘authenticity’ guff, anyone can wear whatever the fuck they want, however they want, and ask to be defined in whatever way they want. But ultimately, it doesn’t matter where a style originated, what it ‘meant’ to begin with, who it defined, and how–no one owns it, anyone can wear what they want, and a little less “this is my tribe, fuck off” and a little more “we’re all just trying to carve out our own niche, who cares?” the better.

“No one owns a trend, a style, a type of clothing or hair cut.”

Hehe, I get that in the superficial sense of this article but sometimes shit can be annoying when privileged people appropriate styles to be seen as “extoic” and “edgy.” I can’t with that shit.

I agree. It drives me mad all these straight girls adopting stuff to be cool. Its like you have everything else. I just want one thing to myself

But it´s not like lesbaians “invent” androgyny. The style that was featured on the 90s mag cover was actually very popular during the 80s with the (dark) wave, undercuts are widely spread among goths and punks, et cetera… Ans because fashion is such a influential thing, it´s simply imposible to claim something as your own and onyl your own.

While I’m sure there were androgynous lesbians etc *before* the 80s, this comment reminded me of a book I read a little bit of at my school library, called “Goth: Undead Subculture.” This was a while ago but it had interesting things to say about Goth culture and gender theory/sexuality! Because it makes a lot of sense I think for a gay person to be drawn to gothic culture, considering you’re putting yourself visibly out of the “mainstream” and it’s a culture that better appreciates gender/sexuality ambiguity or identifications out of “the norm.” It makes me think maybe that’s why I found the style appealing when I was in high school and not out yet, anyway.

http://www.amazon.com/Goth-Subculture-Lauren-M-Goodlad/dp/0822339218/ref=sr_1_3?ie=UTF8&qid=1346897980&sr=8-3&keywords=goth+the+subculture

“adopting stuff to be cool” isn’t that what ALL fashion is?

Wait, I had short hair before I realized my lesbianage. Was I a straight girl adopting it? I mean, I was about 10 when I started having short hair but still…

I think it’s more attitude than the fact that they’re ‘adopting it to be cool’. My head is buzzed (because I want it to be, and I like being visible) and I have a straight friend whose head I recently ~undercut and she’s constantly joking about people assuming things about her based on gender norms and her “lesbian haircut” and I just want to smack her because at the end of the day (or year or whatev), her hair will grow back and she gets to go back to being a ‘normal’ person and not getting “misread”… it’s a lot harder to be brave enough to be read this way when you can’t say “no no don’t worry I’m straight and not-genderqueer, don’t worry” to anyone who questions you. (I hope this makes a little sense.)

agreed – one might see appropriation of lesbian style as cultural appropriation – like Urban Outfitters putting a so-called “Navajo print” on all sorts of things (Flask? Why not!) and selling them in their stores. Stuff like that is privileged people trying to be exotic, like you say. And when straight girls (hipsters particularly) get alternative lifestyle haircuts, wear TRIANGLE-shaped jewelry (did your people have to wear a badge that shape in a concentration camp?), etc, etc, they are trying to look edgy but for them it’s just a fashion trend and at the end of the day they can still bring their significant other home to their parents/get married/etc.

Plus, since they’re privileged, they get people thinking they’re the ones who originated/own the style. I got my glasses specifically to be *lesbian* *femme* glasses and the first thing my friends said to me when they saw them was “Nooo, you got hipster glasses!” No, hipsters have MY (OUR) glasses.

“No one owns a trend, a style, a type of clothing or hair cut.”

So much THIS!

The way someone chooses to dress and style her- oder himself is such a vague indicator. A girl in a studed lether jacket might be queer, but she as well might be straight as an arrow and just be into some rock, punk or heavy metal music. Especially glam rock always used to be (and still is) the home of gender bending styles – think David Bowie, think Iggy Pop, think Cinderella. Someone who looks like a butch might be a nerd (or a huge fan of anything Bill Cosby would wear) and not every woman who looks like a 50s pin-up is a lesbian.

So yeah, no one owns a style. Just relax, DO YOU and let everyone be the way they want to be!

I adore this post.

Don’t you just love living in a capitalist western society where *almost* everything is commodified and consumed by people, especially by the women-folk?

Like, wtf? Boyfriend jeans? Not jeans that fit looser than your usual jeans but boyfriend because every lady must have a boyfriend with jeans. Okay.

Boifriend jeans…I have a pair of those.

Ironically, my two favourite pairs of jeans (both of which had their names sewn on the waistbands) were called ‘boyfriend’ and ‘straight’.

I think this is why I was so confused by straight jeans a a child.

Personally I don’t care much about labels and all, but I’m glad that “lesbian fashion” is being adopted by the straight world.

If queer girls have to stop making assumptions about someone being gay because they “look gay”, maybe they’ll come to stop assuming someone isn’t because they “look straight”. One can dream.

I think it’s also great that straight women become less pressured into compulsive high-femininity as the only valid gender expression available to them.

I agree with most of the things this article says.

But mostly I’m really happy y’all mentioned Alicia Hardesty. I have a serious fashion crush on her. She’s my favorite on Project Runway this season, and I can’t wait until her clothes line is available for sale. Also her dreads are amazing.

I have sooo many mixed feelings about this topic.

Recently, I met a girl wearing combat boots, who had short spiked hair. She was talking about going to the Pride parade. I thought, dayum, a really hot gay chick – nice. Everyone around me gave me shit for “assuming” she was gay – they asked me “what’s gay style? Anyone can dress however they want” (oh PLEASE – there IS gay style, and equating combat boots with queerness ISN’T crazy); “what’s wrong with her hair? It’s cute”. There was a mix of conservative “you calling her a lesbian or assuming she’s a lesbian is OFFENSIVE, because being a lesbian is OFFENSIVE” and liberal “we can’t define people by what they wear.”

But we CAN define people by what they wear. Clothes and hair DO convey something about a person. Being able to signify your queerness IS important. People pick clothes that they feel like reflects their identity in some ways, and sometimes – not all the time, but sometimes – that means they’re trying to come off as queer.

I’m all about straight women being able to dress outside of what is considered typical femininity. And I think queer chicks should be able to dress preppy or feminine or however they want. The problem is, just because everyone is allowed to be butch doesn’t mean I’ll suddenly assume all the femmes are allowed to be gay – because it’s just not true. Most of them will still be straight. If a guy hits on me, I’m not offended. But most girls will still be offended if I hit on them. There’s something safe and comfortable about being able to assume /sometimes/ – even if you’re wrong, sometimes, too. If we can never assume anything, then what? We still live in a predominantly heterosexual world. What’s the right course of action then? Lesbian-only meet-ups? How dull. Talking to every person in such extreme depth that they will reveal their sexuality? Who has time for that?

I just don’t know what the right answers here are. I know we should all be allowed to wear whatever, but when it comes to saying, yes, lesbian fashion exists, and associating certain clothing items/combination of clothing items with being a lesbian isn’t wrong, is that ok? Is it ok to say that? When it comes to trying to figure out if someone might bat for your team or whatever, is it ok to look at their clothes? I mean, sometimes? If it’s not, what do you look at instead?

I’d say thinking someone might be potentially into you because of an alternative appearance is totally okay. Someone talking about going to pride is probably not going to be offended by any polite overtures, even if they don’t swing that way.

Ascribing a social identity to someone for any other reason than them telling you they identify that way, however, is not. That girl you describe might be gay. She might be bi and that identity might be important to her, what with her appearance often getting her written off as “gay” and thus burying half of her identity. She might be a straight masculine person who is just dressing the only way she feels comfortable, not because she is attempting to send any messages. She might not be a “she” at all. Pride isn’t just for gay people.

Well, that’s the thing…what’s the difference between “making an assumption/educated guess – until proven otherwise – so that I can make polite overtures” and “ascribing a social identity” to someone? When someone says something like “oh, that chick is totally gay”, they are psyching themselves up to make a move…if she was like, nah, I’m straight, you’d be like, oh, oh ok darn. This whole “erasure of identity” thing seems so overboard.

In the absence of categorizing and ascribing – momentarily, at least long enough to start a conversation – what do we rely on?

‘Cause like, you sorta contradict yourself – you say it’s ok to think a person might be into you because of an alternative appearance. Well, in this case, if she was straight, she wouldn’t be into me, so I’m also ascribing her an identity at the same time (albeit a temporary one that would change if she identified as something else).

I don’t label myself when it comes to style. I wear men’s jeans, combat boots, a gala dress paired with high heels, tight women’s jeans, women’s perfume, men’s cologne… anything. People refer to me as feminine, tomboy-ish, butch and other terms on the spectrum, and I always tell them that I have no idea what I am, other than myself. I am everything and nothing, you know?

This does get complicated when I go to gay bars. People have asked me if I’m straight because I happened to wear a hot pink shirt that day. When you don’t fit the “type” around here, people don’t pay attention to you. “She must be straight.” It’s tiring, because I feel like I have to change my outfit in order to be a part of the community which I refuse—most of my friends are straight women.

I see this labeling behavior in my classroom as well. On the days that I wear combat boots or clothes that seem out of the ordinary, I regularly overhear students talking about whether I am gay or not. I don’t mind the speculation about my sexuality, but I do find the relation to my style troublesome.

Everything and nothing sounds great to me, but it makes me feel excluded at times. I hope someone else relates to this as well.

I have a name for boyfriend jeans. I call them “jeans.”

(My guy roommate and I have the same pants).

East London = hipster lesbian-haircut mecca

fantastic article.

Firstly, this is why I continue to advocate for Secret Queer Club Decoder Rings (I am aware this policy could be considered exclusionary but sadly my gaydar has a shocking margin of error. Also decoder rings are cool). Secondly, I’ve seen old timey photos of the lesbians of yore and can attest that lesbians have always been chic.

I don’t have much to contribute to these awesome comments except that I agree with the frustration. And tired of being told by nearly everyone that I look like a “hipster” now that I decided to add an overtly queer element into my style. The only time I look “gay” is when I wear something so masculine it makes me feel uncomfortable and inauthentic. I’m just shocked that everyone else feels entitled to put me into these boxes when I really didn’t ask for it….but, like others have said, that just sums up the experience of being queer and being a woman.

Really great article, thanks Gabrielle!