At the start of the 1994 Winter Olympics in Lillehammer, I was 11 years old and the most confusing question in my life was: why is there another Winter Olympics when the last one was only two years ago?

With the excitement of the previous games still fresh in my mind, I had decided I would devote as much of the half-term holidays as I could to devouring as many events possible. I established my base, knelt on the beige living room carpet, inches from the TV.

Coverage of the figure skating program was extensive in the UK because of the return of ice dance pair Torville and Dean, one of a handful of British gold medal winners at the Winter games. The Tonya/Nancy story was not the main event for us, and I would have been glued to the women’s event anyway — a sport where people actually pay more attention to the women! I thought the added drama was welcome, but not essential.

Watching the short program, I quickly determined my favourites. Veteran Katarina Witt was an instant hit, skating to music from Robin Hood Princes of Thieves (a film obsessively celebrated by my sister and I), dressed on-theme in a forest huntress outfit. The commentators were tripping over themselves to praise her grace and artistry, and seemed to treat the fact that she couldn’t match the jumps and technical complexity in her competitor’s routines almost as a positive. She was, they claimed, skating almost purely for the joy of the spectators, the pinnacle of feminine beauty as sport.

Contrast this with my other favourite, France’s Surya Bonaly. I remember the commentators talking at length, and with dismay, about how she skated in straight lines, and somehow this was to do with her having been a gymnast. This, to me, seemed preposterous: firstly, how can you skate straight lines around an ovular rink, and secondly, so what if she did? She had an energy, maybe defiance, that I hadn’t seen in the other competitors. Where others’ forced smiles barely covered their fear, it was fun watching her. The commentators interpreted her style with words like “strong,” “athletic,” “hard-working.” They did not mention she was black. They did not mention she was the only black woman in the field.

The other skater they called out for athleticism over artistry was Tonya Harding. Maybe they made veiled references to the attack on Nancy, but these were BBC commentators. They talked about Tonya measuredly, like she was that embarrassing cousin whose salacious life they wanted to know all about, but were far too uptight to bring up publicly.

I didn’t know all the details about the scandal then — as far as I cared to know, Tonya’s husband whacked Nancy’s knees with a crowbar — but I didn’t need to. There was something about her that I took an instant dislike to: the deep blush that covered her face, the tautness of her skin from the way her hair was pulled back, the way that among all the gaudy outfits, somehow only hers looked cheap. There were so many words I did not have at my disposal then, but I did not need them to decide that this was not a good woman.

The final straw came in her free skate, with the shoelace incident. It was quite black and white to me: she’d come on, mucked up her first jump then gone crying to the judge about her laces to try and get a do-over, hoisting her leg over their desk for effect. She was snivelling like a schoolgirl trying to get her own way, and as a then-schoolgirl who was quite adept at getting my own way, it was an embarrassment to all of us.

It was tantamount to cheating, as was getting your opponent’s knees smashed in. There and then, I shifted all my allegiance to Nancy, who up to that point I’d had little opinion about. My mild disgruntlement at her only claiming silver was more to do with my dislike of the winner, Oksana Baiul, as I couldn’t believe that a 16-year-old could have the grace required of an Olympic champion.

By the end of the 1994 Winter Olympics, I was 12 years old and quite certain I’d picked the right side.

Even before the Olympics, details began to emerge about the attack on Kerrigan, with the whole plot being so convoluted and warped by the legal and media circus around it as well as its inherent melodrama that it’s still hard to be sure what really happened.

We already knew that the attacker was a man called Shane Stant, hired by Harding’s abusive ex-husband Jeff Gillooly and her bodyguard Shawn Eckhardt, via Stant’s uncle Derrick Smith. These men — fantasists about their own capabilities, yet wildly incompetent — met to discuss in detail how they wanted to go about assaulting Kerrigan, briefly toying with murdering her, before deciding simple debilitation was enough to achieve the aim of stopping her skating. This they confessed to the FBI.

Both Gillooly and Eckhert implicated Tonya as an accomplice, which she denied, but some dubious dumpster evidence was enough to bring her to trial when she returned from Lillehammer. So the legal system and the public finally got their chance to openly judge her: did she know about the attack or not? Guilty or innocent?

The outcome was inconclusive: Tonya eventually pleaded guilty to hindering the prosecution, in a bargain that kept her out of jail, but put the final nail in the coffin of her competitive skating career. She was stripped of her titles and banned from all future United States Figure Skating Association events.

I didn’t follow the trial; it didn’t attract constant coverage in the UK, and in those early-internet days there wasn’t the expectation of just finding out what happened. Tonya slipped out of my consciousness, a sidenote to commemorate every four years.

When Tonya resurfaced on Celebrity Boxing in 2002, I was twenty and embraced this news with same enthusiastic irony as I did everything as a student. Too many late nights watching John Waters films gave me a frame of reference that I hadn’t had as a child, and a lexicon to find the word I thought best fit her: trash.

Learning more about what had happened to Tonya since Lillehammer, the many bizarre episodes of her life made her perfect for this treatment: the court case that finally condemned her, if not for plotting the original crime, for the cover-up; the on-off relationship with the husband she didn’t seem able to leave; film and TV bit parts; saving a collapsed woman’s life with mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, and finally attempting to become a professional boxer.

While Nancy had made a few indiscreet comments that undermined the public’s impression of her as an implacable ice princess, she maintained a largely dignified career both in competition and on the pro circuit, which made it hard to make fun of her (although my best friend did once try to convince me he’d seen a documentary saying she’d run off with an air-hostess). Tonya, though, I felt was there to be ridiculed.

It wasn’t until I was past thirty when I started to put any real consideration into the truth behind the events in 1994, and the lives of Tonya and Nancy. Because of my familiarity and minor obsession with the whole affair, I gladly took every opportunity to delve back into it when prompted. And those opportunities were surprisingly regular: at least a cursory mention every Winter Olympics; various anniversaries; one of the protagonists popping up with a new endeavour, prompting another round of think-pieces. And now, of course, the release of I, Tonya, the biopic charting Tonya’s fateful course to the ’94 games.

Because women’s sport remains so ignored, you can guarantee this will continue to happen. 23 years later this is still the biggest media story in the history of any women’s sport, and it’s not a story anyone remembers for sporting achievement.

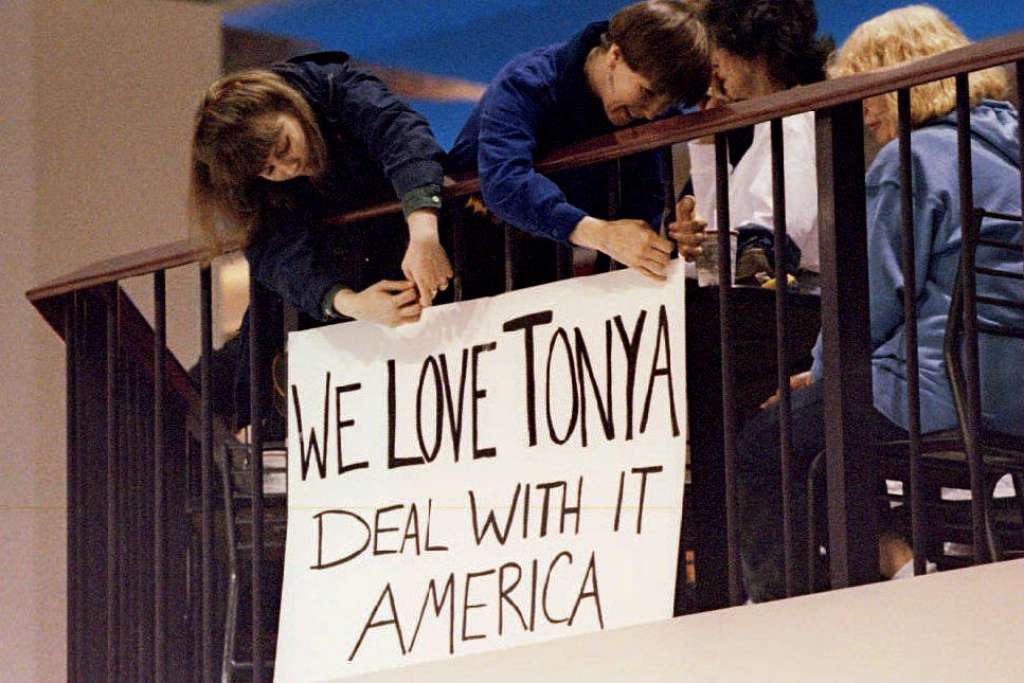

The real Tonya Harding story should be about how incredible it was that a woman, raised in an abusive and impoverished household, managed to become a world-class athlete in the first place. A woman who built the strength and skill to land jumps still only a handful of elite skaters are capable of, practising at a shopping mall rink. A woman whose career was ruined by an abusive and interfering husband that she was unable to get away from for years afterwards, and yet who still reinvented herself multiple times to support herself.

For all I love the concept of the THNK1994 museum, and its ironic look at the media hoopla around the scandal, one of its conceits — and for many participants in the ever-ongoing Harding/Kerrigan discourse — is that you are either Team Tonya, or you are Team Nancy.

It’s another ultimatum to judge: did Tonya know about the attack? Is she guilty, or merely foolish? Is Nancy such a perfect princess after all? I decided that I don’t care about the answers to any of those questions. I just want to us to stop pitting women against each other.

I’m not going to stop enjoying the ridiculous elements of this story, but I think I have the perspective and compassion now to understand what I couldn’t when I was younger, avidly joining in the global event to judge one women competing in an event whose raison d’être is to judge women.

I know I can go to any YouTube video of Tonya Harding skating and see comments that remind me of the opinions I had as a child. I can see how quickly the judgement spirals into hate (well, no surprise there for YouTube comments), and how complicit we are when we fail to combat it. I can remember all the times I’ve been silently complicit as men hurl comments at women that I know are wrong, because it’s harder to speak up and, after all, we were all trained to judge women.

I don’t know how to un-train and un-program a lot of this stuff, but I know there are some things I can do to start.

I can hear the language that pretends to be praise, that is really condemnation. I can understand when words are used to describe a standard only attainable to a certain class or colour, which implicitly excludes the rest of the world. I can decide that if a woman is broke and wants to monetise what she has, be that fame, or even notoriety — this should not open her to ridicule. I can stop any discussion of more than one woman becoming a zero-sum game where someone has to win, and someone has to lose. I can refuse any more judgement.

I, Tonya doesn’t open here in the UK until February. Early reviews are good. Forbes says it indicts the patriarchy. Collider says it forces us to reevaluate the misogyny of those Games. NPR says we, as a culture, are the ones who are implicated in her destruction. Perhaps Margot Robbie will do for Tonya Harding what Sarah Paulson did for Marcia Clarke, one of the other most notable women metaphorically burned at the stake during the mid-90s. Perhaps it will push us past our urge to judge Harding and the other women in her life. Either way, I can now watch Harding’s story with a critical eye and form my own conclusions.

Comments

Sally, I love this. My journey was very similar to yours with Tonya Harding. I was camped out on the living room floor in front of those Olympics (and all Olympics, really) too. I was already excited to see this movie, and now even more so.

I am excited that you are excited!

Do kids even camp out on living room floors anymore?! I hope that the proliferation of media devices has not diminished this!

Sally I LOVED reading about this from you and I am unreasonably excited to watch “I, Tonya.”

Sally! This was a fascinating read and a perspective I never thought to consider. It really makes me wonder how many other news stories from the pre-Internet years, whose apparent facts we’ve taken for granted, might have played out differently if they had happened today.

Robin Hood Princes of Thieves? Sally we could have been the best of friends as pre-teens

Carms, it’s not too late

Let’s sing Bryan Adams together and make fun of Kevin Costner!

You know it’s true

Everything I do

I do it for destroying the patriarchy-ooh

I ruined that VHS tape watching it over and over and over

A great read, we had similar journeys about Nancy and Tonya but I have to say… Team Yamaguchi here.

Team 13-year-old Michelle Kwan who technically qualified for the Olympics that year, but was relegated to alternate and conceded her spot to an injured Nancy who was unable to compete in the actual qualifier. That’s kind of a long team name, though.

Team All The Skaters

Although Michelle Kwan was totally hard done by

Great article! Thank you for sharing your thoughts. My favorite line in your piece: “I just want to us to stop pitting women against each other.”

The first few paragraphs brought back to so many memories. I am pretty sure Katarina Witt was my reason for coming out to myself and Surya Bonaly will always have a special place in my heart for her amazing, illegal back-flip in 1998.

I never will understand why it was illegal for women to do back-flips in competition!

I would blame the patriarchy, as usual

I think because no-one else in history (including men) could do the same kind of backflip as Surya Bonaly and therefore they had to ban it because they could not cope with her excellence.

Sally, I loved this! I was also super into this story as a kid, also 11 years old, also obsessed with the olympics because that’s where women’s sports were actually, I dunno, in existence at that point (at least as far as I could tell)? And Nancy Kerrigan is from close to where I live so I think it was on the news here even more than it was anywhere else except I guess around where Tonya Harding is from, probably.

Tonya was A Villain and Nancy was A Hero. But also everybody made fun of Nancy for the particular way she cried after having her leg smashed with an iron bar? So much of the coverage was so unkind.

Anyway, Surya Bonaly was my favorite and I was so angry on her behalf because they wouldn’t let her do backflips on ice skates which was the coolest thing I could ever imagine.

I still get so much feels whenever I think of Surya Bonaly’s defiant backflips.

Evidence suggests that while everyone obsesses over Team Tonya/Team Nancy, the cool people are Team Surya.

I gleaned said evidence from this comments section.

Reading about your learning process invited me to examine my own patterns of misogynistic thinking and come up with at least five instances where I was too quick to judge.

In my opinion, these kinds of first person pieces are essential when it comes to making a change; this is how I messed up, this is what I have learnt since, and here’s what I did/am doing to do better. It’s often easier (though sometimes necessary, don’t get me wrong) to point the finger at others or label problematic behaviour as wrong and leave it at that, but I think leading by example is in many cases a far more effective and inspiring way to make a point.

Also, I had never heard of any of the people mentioned in this article, so I initially thought this was going to be an salty piece about Dana Fairbanks’ fiancée and how fucked up she was.

Justice for Mr Piddles!

Why was season six not this

Rous you make excellent points and now I feel weirdly compelled to make a case for Dana’s ex-fiancée even though it is probably impossible

I was obsessed with figure skating as a child and I remember being staunchly Team Tonya as the events unfolded despite the fact that I usually gave allegiance to brunettes. Even at such a young age I recognized that Tonya was the underdog. I knew the commentators didn’t like her (just like they didn’t like it when Surya did those incredible backflips), and I knew they favored Nancy Kerrigan’s posh, all-American prep look over Tonya’s bright 90s prints. I can see now that it shouldn’t have been an either/or situation, but over the years I have taken every opportunity to stand up for Tonya Harding whenever her name gets brought up. I’m so excited for the film, and I hope that maybe we can finally put the Tonya jokes to rest. Seeing her promote the film with Margot Robbie has been a joy!

Team Tonya!

I feel like a really need to add a caveat here.

During the 94 Olympics, when the whole rivalry was being framed— I was firmly Team Tonya. Later, as more details were revealed, and all the complexity unfolded, it was tough to stick to my initial allegiance.

And also I wanted to acknowledge, that I realize my b/w read of the rivalry totally goes against all the nuance above.

Where is Erin, though?

Carms, are you implying we need a Mommi check on Tonya?

I’m not obsessed with figure skating, but I’ve enjoyed enduring “jokes” about both sides over the years.

As an older adult, though, I feel so much for Tonya Harding and what she endured and survived to thrive at the level she did.

I’ve been obsessed with this story since I heard the new Sufjan Stevens’ song about her. I’m gonna watch a bunch of documentaries while I wait for I, Tonya.

Loved this article, very relatable and familiar change in perspective. I have so much respect for Tanya Harding now, dang.

I watched the ESPN 30 for 30 about Tonya Harding. It was basically her blaming everything and everybody in her life for screwing her over. She didn’t take responsibility for any of the decisions she had made as an adult. I didn’t pay attention to the media coverage leading up to the Olympics that year. I was young and having fun so I wasn’t invested in it. I don’t remember really having an opinion. When I saw her interview I became very annoyed. At some point you have to accept responsibility for your life. Otherwise, you will be trapped in a cycle. It should be interesting to see if she has changed.

i loved this, especially the idea of not pitting women against each other. such a great read!

For those who love Surya Bonaly as much as I do, this podcast of her story is really interesting: http://www.radiolab.org/story/edge/

Being Norwegian, Lillehammer 1994 is very close to mind. I was 10. There was the Lillehammer ice cream. Actually as the olympic torch came through my town (which nowadays is most famous for having the ‘worlds most luxurious prison’), we got free ice cream (it was called ‘flakkel is’ which would be ‘olympic torch ice’) We learnt to dance the ‘OL-Floka’ – a kind of dance designed to keep oneself warm in cold weather. You basically just hit yourself with yourself with your arms.

We got a special holiday for one week. The non-holiday week my teacher sneaked in some very high tech mini-tv to lessons (remember this is 1994) and thought us students wouldn’t notice. Norway was good at speed-skating!

I drew pictures in my history/society book of ice-dancers complaining and showing their shoe-laces…

But as I have grown up, and am a massive Sufjan Stevens fan, this article still makes me think mostly of Sufjan’s newest song, entitled ‘Tonya Harding’/…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PUvVjWR3zTQ

I meant ‘fakkel-is’ :)

I MUST TESTIFY DR.MACK201@GMAIL. COM BROUGHT BACK MY HUSBAND WITHIN 48HOURS.

WHY WOULD YOU DO THAT DR MACK? YOU SUCK

sally this was so great! i had a similar journey and tonya harding was one of many women (like marcia clark) i realized a decade later i had judged based on how the patriarchy told me to, and reconsidered entirely

Powerful and moving! I started re-evaluating my feelings and opinions on Tanya within the past couple years and I’m rather excited about the movie.

I also want to start quoting Alan Rickman. >.>

Great story and great food for thought. Whenever I heard the inevitable “poor white trash” comments about Tonya, my poor (literally trailer park) white trash heart died a little. I don’t know just how involved she was in the whole ordeal, but getting out of poverty is a big deal and sometimes one that results in desperation. I look at her a lot differently now as an adult than I did as a young person then as well. Thanks for this.