When I was very young, I refused to sleep in my own room. I always wanted to sleep squished between my parents, right in the middle of their king-sized bed. My parents told me I often fell asleep on the floor with the dogs at the South Korean orphanage I stayed in before my adoption. That’s what the adoption agency told them. That’s why they thought I wanted to be so physically close, their body heat comforting my pudgy little toddler frame.

I don’t know if that’s true, but I have always loved dogs and animals. I had pets from the moment I arrived in the U.S. I have almost never been without a pet or three or four or more. We had puppies and cats and hermit crabs and tree frogs and hamsters and a guinea pig who was my whole world. Perhaps it’s because I was adopted into a family that doesn’t look like me in a country that isn’t the one I owe my heritage to, but I’ve always longed to belong. More than that, I’ve always wanted to love and nurture others.

For a lot of my life, I simultaneously desired to be loved and felt inherantly unloveable. My parents loved me deeply and were very affectionate. I felt loved and cared for by my family. It wasn’t that. It was this feeling I carried in my gut, that I was somehow different, that I just never really fit in, that I was always going to be outside looking in. That, and the internalized racism I carried with me into my teens and beyond.

Animals, though, didn’t care that I had squinty eyes or that I was chubby or that I looked different than everyone else. I could trust them and I could give them all my love, without fear that they would betray me or expect anything more from me.

I was convinced that I could speak telepathically with one of my family’s golden retrievers. We’d had Finnigan since he was a wee puppy, since our other dog, his mom, gave birth to him in our bathroom. He was a weird dog, too big and goofy-looking and terrified of thunderstorms. I thought we had a special bond and I told Finn my secrets and I truly believed he could speak back to me if I stared long enough and hard enough into his big, brown eyes. I had an overactive imagination and I wanted to believe we had a spiritual connection. I still talk to my animals (though I no longer believe they can telepathically speak back to me). I still believe we have a special connection.

I’m writing this sitting cross-legged on the floor of the bedroom where our bunnies have run free since we bought this house in 2012. Their guinea pig siblings (the wiggles) romp above them, in a 13 square foot enclosure that sits atop a long table. When we moved in, the first home unimprovement we made was taking the door to the bedroom off its hinges, replacing it with a plywood-framed screen door, the kind you might put on your shed.

We joke about our second floor indoor barn and it’s kind of that, but more like a messy, dynamic bunny habitat, littered with half-gnawed cardboard castles and wooden chew toys and an open dog crate that houses their litter box and hay bin. When I mention our free-range bun room to people who don’t know me well, they’re a little weirded out. Possibly because not a ton of people have access to an extra bedroom for their pets, but more because people aren’t raised to or don’t see their pets as worthy of that much space.

I respect cultural differences around companion animals. I’m not hating on anyone who makes different choices. Our bunnies lived in large dog crates when they were younger, when we rented apartments. We knew we’d let them be free-range when we had a house of our own. We want them to be their happiest, healthiest selves. Our furkids are members of our family. They are the only living creatures (humans included) in our household who get a window air conditioner in the summer. We buy them the best food, allow only the healthiest treats, and prioritize their needs over ours. In return for being little spoiled brats, they give us unconditional snuggles and cuteness that is almost unbearable. I feel like they love us. It’s hard to translate animal love into human feelings, but we like to think they do.

My spouse and I are very different people, but we are similar in that we have a hard time being vulnerable. Accepting love is hard, giving it unconditionally is a huge leap of faith. With our pets, whether they love us in a tangible way or not, we can love them wholly and without reservation.

I’m lucky my spouse falls in love with pets as quickly and deeply as me, for reasons completely his own. We accept our pets with all their quirks, even when they have behavior challenges (:cough: :cough: Limburger, the biter adopted rat who couldn’t be touched nor tamed). We’ll do whatever we can to make their lives a little better, a little safer, a little longer. Waffle’s love for his first cat, Kitty, rivaled his love for me. No, it surpassed his love for me. If there was a fire and our home was burning down, Waffle would have grabbed Kitty first. “You have a better chance of saving yourself,” Waffle would say as I was trapped beneath a ceiling beam. Kitty and Waffle were inseparable and sometimes insufferable and their relationship predated Waffle and mine. When it came time to say goodbye to Kitty, I wasn’t sure Waffle would be OK.

It was almost four years ago when Kitty took her last sleep. She was a foster cat, so we never knew exactly how old she was, but she was at least 10, maybe 12. She was fairly healthy for her entire adult life, up until the last two years. In 2009, Kitty was diagnosed with renal disease, kidney failure. She began to age rapidly and got very frail and tired. We bought carpeted pet steps so she could comfortably get to the bed and the couch. We didn’t know how long she’d live, but we managed it with a special diet and a gradually increasing list of medicines. We put litter boxes in all her favorite areas, so she could easily access them. Eventually, she stopped using them at all and we said, “OK,” and invested in really potent pet clean-up supplies and loved her anyway. We cut the mats out of her long fur when she was unable to groom herself. We helped her stay alive and, in the end, we helped her die peacefully.

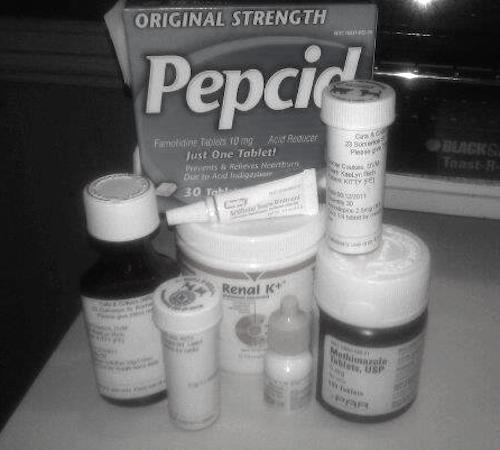

I became skilled at dispensing liquid medicine and hiding crushed pills in increasingly complex ways. I bought a pill splitter, mortar and pestle, and a blue two-week pill box. We couldn’t go anywhere overnight for the last year or so because she needed various medicines at various times of day and I didn’t trust anyone else to get it right. She was sick, yes, but she wasn’t unhappy. It sounds hard to believe, but she still had a lot of life. She still purred and laid in sun spots and would fall asleep belly-up in our arms.

Kitty always wanted to be near us. Towards the end, she was losing her vision and she’d call out in the middle of the night. We’d yell her name and she’d follow our voices and climb the cat stairs up to the bed and curl up in Waffle’s arms and purr and purr. She knew her way around the apartment, even as she lost her sight. Somehow she never ran into anything.

It was hard watching her get old. It was hard to know when it’d be time. It was hard to guess what she was thinking and feeling. It was hard to say goodbye to her.

We knew we had to make a decision when she started having trouble walking. With all her other health issues, it was too much. Our vet, who’d worked with Kitty through all of this, made special arrangements to come to our house for the final visit. Kitty hated the vet. It sent her into a fevered panic. She would poop in the cat carrier and arrive covered in her own stink. She’d yowl all the way there and back. She’d hyperventilate with her tongue lolling out of her mouth. On the day of the final vet visit, Waffle and I sat with her all day, giving her special treats: cheese, bits of chicken, the “bad” cat food, tuna, turkey baby food. We relaxed together on the couch, holding her when she wanted to be held, letting her rest when she wanted to rest, letting her pee all over her favorite couch cushion. It didn’t matter. We just wanted her to have a good last day.

Waffle and I attempted to not break down at the same time, to take turns sobbing. We laughed about our favorite Kitty memories and stories. We took pictures of her sweet face as she lay peacefully with us. I tried to make space for Kitty and Waffle to be together alone, but he encouraged me to stay. “It’s OK,” he said, “You were her mommy, too.”

When it was time, the vet came up to our apartment and set up in the kitchen. Waffle carried Kitty, tucked into his arms like a baby, and he soothed her and held her while our veterinarian slowly pressed the plunger on the syringe. And then it was over. But it’s never really over. There were still her things around the house, all the special kidney diet food that we donated back to the vet office, her water fountains and her little jackets (yes, she liked to wear small dog clothes), her little tufts of hair floating across the hardwoods, and the smell of her, the memory of her everywhere.

There are many jokes about queers and our relationships with cats. Like all stereotypes, there is some truth behind it. Many of us have felt unloveable, untouchable, at some point in our lives. It makes sense that we would imprint on our furry friends who don’t judge who we are, don’t inquire about our life choices, and provide affection when we feel like we can’t connect with other humans. This is the greatest gift they give us, the act of simply being there when we need them to be.

Waffle has a hard time with words. Some nights, early in our relationship, I would wake up at night and hear him whispering to Kitty, telling her things he wasn’t ready to tell me yet or ever. I have a hard time letting people in. I seem like an open book to those who don’t know me — the confessional poet, the activist with the megaphone — but those are just some of the many masks I wear. I’m a social chameleon. I can get along with anyone. I only ever let anyone see one piece of me at a time. It makes me great at networking, horrible at developing real friendships.

My biggest fear is opening up to someone and then being abandoned, because it has happened before, because I was abandoned when I was just a baby for reasons I’ll never know, because who I really am might be too much for someone to handle. It’s easier to be strong and protect my heart than to let it be broken wide open. My pets, my furbabies, have never let me down like that. I care for them. I feel safe with them. If only they lived a little longer, though in some ways it is reassuring to know that I will always (hopefully) live longer than them. I will always be someone they can depend on. Our home will always be their home.

Saying goodbye to our furry family members never gets easier. In the past 11 years we’ve been together, Waffle and I have shared 12 pets, 12 furkids. We have seen nine of them pass, the most recent the day before I wrote this. Every single damn time, it hurts. Every single time, I wish we’d had longer to say goodbye. More often than not, we have to make the choice for them: Do the good days still outnumber the bad? Are they still happy? Are they eating on their own? Do they have a good quality of life? Is there any chance of recovery? If so, what is the physical toll on them going to be? What are we feeling? What are they feeling? Are we asking them to live for us or do they want to live? What is the most humane thing to do? Are our emotions getting in the way of reason? What is right for them?

This past Saturday, we brought our bunny, Aphrodite, in for her final vet appointment. We have had her since she was just two months old, a little bundle of fuzz who hopped her way into our lives back in February 2007. She was our love bunny, our two-year anniversary/Valentine’s day blessing to ourselves. Aphie was a queen bee. She was a smaller breed, a Holland Lop, and she looked very demure and unassuming. But she had a metric ton of attitude in her six pound body. Aphie was the boss of us, of Kitty, and of the house. Up until the very end, she’d come over and headbutt my foot to let me know she’s still the big bunny. When she was younger, she was an adorable menace. She’d tug on the curtains in the living room with her teeth until they came crashing down and then nibble the ends of the curtain rods, looking triumphant. She’d knock over houseplants and then play coy when we caught her snacking on them. She’d pee on any furniture we didn’t block access to, especially soft cushions. (She was fully litter-trained, but she just loved the feeling of soft cushions for relieving herself.) She dug up and pulled up corners of the carpet in our rented apartment. She nommed on our books and once “workshopped” a poem of mine with her teeth. Her critique was harsh.

Aphie was our furbaby for over eight years, during four of which she was an only child. Buns like the company of other buns, so in 2011, we adopted a friend for her: Gandalf the lionhead with his fluffy grey beard. They disliked each other immediately. The hostility continued for almost a year. We had to keep them in separate crates and let them into separate parts of the house for exercise time. Aphie would sometimes jump the gate between their areas and chase Gandalf into a corner. Bonding them seemed impossible, but we don’t give up on our pets. We knew when we adopted Gandalf that if we couldn’t bond them, we would keep them both and we did.

I get that there are real and serious reasons why people abandon or surrender their pets. I have a hard time understanding it, though. I know I shouldn’t judge so harshly and for some people it’s the right thing to do, but I don’t think I could ever do it. I know what it feels like to be abandoned and rehomed. I love my family and I feel very lucky to have had a good and loving adoption experience, but I also know that it changes you. Being left behind or given up changed me, in ways I didn’t fully understand until I was an adult. I know people give up their pets in the hope that the animal will have a better life. Each time we adopt a new pet, we are glad that we can give them a good life. Still, I can’t imagine making the choice to surrender an animal except in the very most extreme conditions. Once an animal has entered our family, they are family for life, for the rest of their life. That is the promise my family made to me. That’s the promise I make to my furry family.

We didn’t give up on Gandy and Aphie. When we moved into our first house in 2012, we tried bonding them again, hoping the neutral territory would make them play nice. Finally, after a week of supervised sessions and lots of patience, they fell in friend love. We moved them into their bedroom and they were BFFs right until Aphie’s last day.

After Aphie and Gandy became friends and roommates, she chilled out considerably. She was still a destroyer of worlds and they certainly got into trouble together sometimes, but she had a friend to hang with now. I’d walk by and see our buns squished together side-by-side, like two cute little loaves of bread. They would sit in the hay bin and munch together. They would tag-team a cardboard box and rip it to shreds. They were often in the same favorite box, peeking out the cut-out windows at us as we passed by their room. Gandalf worshipped her. She let him. He generously bathed her ears and face every day. He let her eat first when they got their greens at night. They were very happy together.

When Aphie got sick the first time, this past February, we had to take her to the emergency vet. We found her grinding her teeth one evening, hunched up and acting strange. It happened suddenly. She had seemed fine earlier in the day. The emergency vet thought it was gastrointestinal stasis, a potential killer, but very treatable and fairly common. It was the night before we were supposed to leave for a vacation. We debated whether to go or not and decided it would be OK. GI stasis can usually be turned around if you catch it fast. Our petsitter works for our regular exotics vet office and was very capable of feeding her and monitoring her health. Our petsitter told us it would be fine to go. We hesitantly got on a plane. However, the next day, she seemed to be getting worse, not better, and our petsitter took her into the vet office.

Aphie ended up being boarded at the vet’s for almost a week. It wasn’t just GI stasis; her kidneys were failing. With absolutely no hyperbole, I believe our petsitter saved her life. I felt so bad for being out of town. I considered flying back, but even if I did, there was nothing I could do while she was boarded for treatment. There was a point where we weren’t sure if it was time to let her go. She was very sick. We weren’t there with her. We couldn’t see her to say goodbye. We couldn’t see her to assess how bad she was. The vet said aggressive treatment was an option, but it might not work. I sat in my hotel room with my head in my hands and cried and felt like I’d failed her.

Hesitantly, we agreed to aggressive treatment, with the caveat that we’d stop if it wasn’t working. Like the fighter she is, Aphie made a sudden, very positive turn-around. Days later, we were home and she was home with us. We had to force feed her three times a day and give her fluids under her skin and a couple other medications, but she was rapidly improving. She came all the way back to full health. The vet called her a “miracle bunny.” But a few months later, she was grinding her teeth again. It was back to the vet, back to the fluids and the force feeding, and with lots and lots of love, she regained her health a second time.

This time, we kept giving her subcutaneous fluids under her skin twice per week, supplemented with vitamin B to stimulate appetite. We set up an IV station outside using a coat hanger, a door frame, and a folding tray table. I became skilled at sliding an 18 gauge needle just under her skin. She was herself again, lovingly butting our feet with her head to show her dominance, chasing Gandalf around the room, tearing into her greens every night, flopping out with her feet kicked to the side and her white underbelly exposed, pushing her head underneath Gandy’s to force him into grooming her, giving us disapproving bunny side-eye when we rationed her treats. She was back. She was not 100%, but it was enough. She seemed happy again.

And then one day recently, we noticed she was slowing down again. Her stool was off. Her attitude was different. We gave her fluids and they didn’t plump her up and bring up her energy the way they usually did. Waffle stood in the bathroom door, brushing his teeth, as I gave the wiggles and buns their nighttime feeding. We had the conversation.

“Do you think it’s time?”

“I don’t know. Do you?”

It’s easier when the answer is very clear. It’s easier when they take a sudden turn and there’s no other humane option. It’s easier when they look at you and you know that they know it’s time. It’s easier when they give up and just close their eyes and say goodbye for you. Aphie was a fighter. She’d never, ever give up. We didn’t want to give up on her.

But there is a point when the bad days outweigh the good. With small critters, disease progresses quickly. We know this. We’ve nursed and loved many small furry babies and we’ve made the decision many times. There are times we think we should’ve made the decision earlier. There are times we wish we’d tried more medical intervention or gone to the emergency vet. Once a small animal is sick, you have days left, sometimes hours, to treat it or it will often end their life.

The thing is, animals know when it’s time. Animals don’t fuss over death the way humans do. Fear is instinctual, not intellectual. They may try to fight for their life, but they also know when it’s time to find a quiet corner in which to die.

Aphie had come back from critical condition twice already. She tolerated the fluids, but she hated force feedings. She hated us when we had to give them to her. The very last time we gave her fluids, she started breathing heavily out of her mouth. Rabbits are nose breathers. They don’t breathe out of their mouth unless they physically have to or are extremely stressed. This is often the prelude to a fatal heart attack.

Rabbits are simultaneously super resilient and incredibly delicate. Maybe this is why I relate so much to them, why I felt so close to Aphie, in particular. She was the alpha bun. Like her human mom, she was a tough bitch, but she was vulnerable, too, and she rarely let on when she was in pain. Rabbits are able to quickly recover from minor injuries. They have a high pain threshold and hide physical pain until it is critical. However, something as simple as a loud noise or dog barking can scare a rabbit to death, literally. In the wild, the sound of a predator triggers a heart attack to save them from suffering through a painful attack.

The first time Waffle found me hiding in the corner of my closet crying, he didn’t know what to do. We’d been dating for several months, but I’d never cried in front of him, not with real emotion. He said later, when I’d calmed down, that it scared him. He didn’t know I could lose control like that. Quite frankly it scared me, too, to be that small and vulnerable in front of him, so early in our relationship. If I could have died of a silent heart attack right then and there, I would have.

Aphie, however, was never afraid of loud noises or other animals or anything. She was fearless. She was raised in captivity, lived with us in a city her whole life, shared a house around cats, and had no natural predators. When she started hyperventilating as we were giving her fluids, we knew it’d gone too far. We knew it was time. We stopped and put her back in her bedroom and I cried and I said “Ok.”

The next morning, I came into her room before I headed to work. She nudged my foot with her head, prompting me to pet her and give her treats. I thought maybe we did have more time to treat her. From work, I texted Waffle that maybe we should wait a few days. But Waffle said, as of that afternoon, she was sitting in the box — the one we call the “death box” — the one she sits in when she’s not well, when she’s preparing to die. She looked tired. She wasn’t moving much. “Ok,” I texted back, “You’re right.”

I made an appointment for the following morning. Our petsitter answered the phone at the vet office. “I’m so sorry,” she said, “I’m not working tomorrow, but give her love for me.”

As soon as I got home from work, I went to their room. She didn’t look well. She didn’t move from the box when I came in. Aphie was a lap bunny. She loved to cuddle. But she didn’t seem to want to be touched, so we just sat in the room with her, not making too much noise. There were moments when her old self came through. I gave her some of her favorite treat mix and she came rocketing across the room, nudging Gandalf’s head out of the way and assertively putting her front paws directly into the food dish. But when she was done, she seemed out of energy. It took everything out of her to get that excited.

Mostly she just lay in the death box. She started mouth-breathing again. In less than 24 hours, my feelings had gone from “It’s probably time,” to “Maybe she’ll be OK for a little longer,” to “Fuck. I think we should have taken her in today.” Gandalf checked on her periodically. She let him groom her ears and face and he laid next to her for some time. I think Gandalf knew she was sick. I think he knew she was going to leave us soon. Towards the end of the day, he left her side and went to sit in a box by himself.

By the time we got to the vet the next day, it felt like it was already too late. She was exhausted. She was breathing hard. It was the most humane thing to do. At the vet’s office, I tried to take her out of her carrier to say goodbye and she panicked. She struggled back into her carrier and couldn’t breathe and she had a heart attack, in her carrier, in a patient room at the vet office, moments before the procedure was supposed to happen. I saw it through the carrier door, her breathing quickened and then she spasmed. Waffle was holding the carrier door closed, because it seemed like she might knock it off the table or fly out onto the floor as she slammed into the walls. And then she fell over on her side and everything was silent and nobody moved for a second. I came back to reality and ran into the hallway to get help, but then I didn’t know what to say or what to ask for, because it was over. I just stood there looking upset for a few seconds, with my mouth hanging open. The staff looked at me. I closed my mouth and went back in the exam room. The vet came in right after me. She gently laid Aphrodite’s unconscious body out on the table and put a stethoscope to her chest. There was a faint heartbeat. She stroked her side and gave her the final injection and Aphie’s little heart stopped and she was gone.

The vet gave us a few minutes alone. Waffle was (unsuccessfully) trying not to cry. I was sobbing relentlessly. I gently stroked Aphie’s ears, like I had done all her life, like she used to love when she would fall asleep on my chest. I pet her cheek and kissed her warm little head and Waffle and I used all the tissues they left for us and I wondered if there was anything we could have done sooner, done better. Maybe we should have taken her in that first night, when we started to suspect she was going downhill. Maybe we should have gone to the emergency vet the night before. Maybe I shouldn’t have tried to hold her right then. Maybe we could have avoided the heart attack. Maybe she would have had a heart attack while they were giving her the injection. Maybe we should have ended all of this months ago. I don’t know. It’s hard to know when it’s time. It’s hard to know what they want. It’s hard to not want them to live.

I’m writing this sitting cross-legged on the floor of the bedroom where our bunnies have run free since we bought this house in 2012. There is one bunny here now and I’m trying to love him as much as I can, as a human who doesn’t speak bunny very well. We’re sad, but he seems mostly OK. They say you should let animals see the body of their friends when they pass, so they understand that they’re dead, but we didn’t have that option with Aphrodite and Gandalf. He seemed to get it right away, anyway. He seemed to know she wasn’t coming back. I think maybe he knew before we did.

Gandy was always more shy, but he has been coming out to see me more often. Right now, he is laying in his hay bin. I’m sitting here on my laptop. I’m thinking of Aphie. I don’t know what he is thinking of. Do bunnies grieve the way we do? Does he miss her or does he just feel lonely or is he OK? It’s hard to tell. All I know is that we’ll be here for him. He’s family. He’s ours for life, for his whole life. So I’m giving him extra treats and extra love. We’re sitting here together. We’re all doing the best that we can.

Comments

Kaelyn I am bawling at work. This was beautiful.

I never EVER got to say goodbye to my beloved pets. I went to school one morning, age 12, and came home at 4 pm to the dog missing. I called my mom at work and she told me she’d found the dog paralyzed and took him to the vet. We were pretty sure there was nothing to do, and apparently he was in really bad pain. The vet put him to sleep that night I think, or the following morning. He looked fine the day before, and I didn’t bother saying goodbye to him in the morning as I rushed to school. I cried every night for 6 months after he died. (this is how I learned about grief).

I was abroad in the US when my mother sent me an email, I was 20. She said the weather had been really really cold for a few days, and the cat chose to stay warm inside instead of going out to pee, and that had never happened, so my mom didn’t think of getting him a litter box. His kidneys rapidly shut down and he was put to sleep as well. I cried the whole day at school, an ocean away from my family. I hadn’t seen him in 6 months.

I was in the South of France when my last dog died, 3 years ago. I was seeing her every time I went home to my parents, and she was so sick, every time there was something new. Every time I left I knew this might be the last. When mom told me that finally, the skin over the abscess on her elbow cracked and that it would never heal and she would develop an infection from it very quickly, the vet said it was gentler to let her go. I didn’t get to say goodbye that time either.

In retrospect, there is a pattern of the vet (two different ones over time) and my mother both choosing to put these animals down every time, rather than making them battle a disease that would be painful for everyone involve, cruel some might say. But I was never involved in that decision process and I have no idea how the alternative feels.

I’m glad you got to spend that last day with your cat, it’s beautiful.

Thank you for sharing about your lovely pets. I’m so sorry you never got to say goodbye. It sounds like your pets had good and happy lives and you have lots of great memories. I hope that you are comforted by those things. I really do think that euthanasia is the most humane option when an animal is very ill. It’s such a hard decision. There are no perfect answers.

I’m reading this with tears streaming down my face, in the room with my two rat men, one of whom is huge and healthy, and the other of whom is very sick but fighting. It’s a journey I’ve been on many times before with these brief, brilliant candles of life. How they’re suddenly old. And losing weight. Marius licks emergency food and medicines mixed in mango lassi from my fingertips. Feeding him takes ages. I have to chase him around the sofa to persuade him: one instant he’s shoving me away, the next he’s happily lapping it up. He’s rambling around the bed now, looking a little brighter but also maybe more restless. Piling on top of his huge brother, scooting under all his boxes. I hoped he’d get better from this (the vet’s not quite sure what it is), but I’m starting to accept we’re probably coming to the end. Thank you for writing about loving these little gorgeous love monsters. How they can take over your whole life at the end, and it’s absolutely, unquestionably worth it.

I’m so sorry to hear about your sick rattie. Five of the pets my partner and I have adopted were beautiful little rats. They are amazing pets, so gentle and smart and affectionate. Their little lives always end too soon and often with serious health complications. Two of our went from chronic respiratory infections, one from heart disease, one from tumors, and two from…just lots and lots of old age sickness.

I hope your little guy rallies and if he doesn’t, that you have lots of beautiful memories of him. They really do take over your whole life, especially at the end, but I agree is it absolutely worth it. Scritch him for me!

Sending you both lots of <3

Well, file this one under “Do not read at work with door open”. Students keep walking by and I need to dive under my desk to prevent them from seeing me ugly cry. I guess I *could* close the door, but that requires walking 4.5 steps.

My bunny was my best friend growing up. He has been gone for almost 15 years. I still cry over him. He had such attitude, loved bananas, and would bite my sister. Pretty much the greatest pet ever.

Sorry for affecting your professional decorum! If it makes you feel better, I cried about 10 times while writing this, so…

Bunnies are such brilliant and rude little creatures. I love them! They have so much personality! Your bun sounds like a wonderful guy. <3

I cried the whole way through this article, then I cried some more reading the comments. I’m just so glad my cat is healthy and a complete snuggle butt right now. There was a time where I was seriously worried about her, as she had several operations to remove a tumor, but thankfully, the cancer turns out not to have spread, so we should have many more wonderful years together.

I hope you have many, many happy and healthy years together! Congrats on beating cancer!

This is going to be the The Ugly Cry thread and I’m okay with this.

My family tends to treat our cats like demi-humans which means going to great lengths to get along with them and keeping them healthy.

My cat Whitepaws was a fattie who had to get a lot of work on his ears when we found him. He came begging around our house one day and he was a sweet if somewhat stupid. Eventually he developed diabetes so we didn’t know what to do, but the best option seemed to be giving him insulin. He was okay, but he grew thin and the end of his life was a lot of pain. That’s one thing my mom regrets doing for him because it’s possible that his life would’ve been a lot better without the insulin. We’ll never really know. But he was such a good kitty. All cats like to go hunting, but we think that there were some people hanging out in the woods behind our neighborhood; Whitepaws would come home with salami or a chicken nugget as if he killed it for us to teach us how to hunt. He was very tolerant of me doing kid stuff like trying to dress him up or awkwardly put jewelry on him.

The last cat I had was Ceceille. She was beautiful. And playful, even in her old age. She was also a bit of a little shit who had a human-sized, grown-up hatred of dogs (I didn’t learn until after she died that she would seek out dogs around our neighborhood to beat up. Those dogs never did anything to her. She did it with forethought and intent. Such a little shit) I think of all my cats, I miss her the most. I picked her out at the pound when my cat Lucky died (I found him dead in our yard. My parents made me go to school that day anyways. I still wish they hadn’t.) I was ready to say goodbye when she reached 20. I could handle that. But then when she turned 17, she developed a sarcoma in her mouth. Aside from that, she was healthy. We thought about putting her down. But what turned my mom around was visiting her grandmother for the very last time and seeing how her grandmother didn’t quite get the treatment she needed. We came back and my mom said, “I’m gonna ask the vet for some chemo treatments for Ceceille. She’s sick and she expects us to help her. It would be wrong not to.” For a while, she got better. I left the country for a few weeks aware of the possibility that she might not make it through. I came back and found out that the day I came back, my dad took her to the vet because she had stopped eating. I know it was a big deal for my dad to it because he didn’t want to say goodbye either.

A year later I found myself crying all the time for no reason, and I realized it was because for the first time in 17 years she wasn’t around. She didn’t love us the way that humans love each other, but I am certain that she loved us in the way that animals can. I promised myself after her that I wouldn’t get another cat for at least five years because I knew I wouldn’t be ready.

It’s been almost five years and I’m almost ready to have another cat again. I have to keep reminding myself to find a new cat, not one just like her. Finding that would be impossible. It’s time to fall in love again.

Well now I’m crying, too. Thank you for sharing these beautiful stories of your pets.

I hope you find a new cuddle buddy to fall in love with. We have another cat now and he is nothing like Kitty, but he is perfect for us and has taken his rightful place as Waffle’s #1 best friend. I’m happy for you that you’re ready to bring a new love-buddy into your life and home!

I wasn’t prepared for this article – but thank you so much, KaeLyn, for putting into words feelings I ever fully realized.

While reading I was transported back to the animal hospital office at 17, rivers of tears pouring down my face, while my beloved cat Lavender was put down. I was in complete shock.

Just two days before, his usually incredibly sweet, affectionate behaviour had completely changed, and he became withdrawn, panting and aggressive, just a few days after my mother had decided to get a second cat. An incompetent vet diagnosed him with asthma, but my stepfather drove him during the night to the animal hospital for a second opinion, and they found that he had advanced throat cancer.

I woke up in the morning to my family snapping at me, announcing flatly that we would lose him. For months after his sudden death, I felt horribly guilty – he was my cat, I should have noticed something was wrong, I should have enjoyed more deeply the ten years we had together, I tortured myself thinking of all the times I neglected to play with him as a child because I was distracted by other things. My dreams were filled with streaks of orange tabby. I never spoke about it, because I was ashamed at feeling so deeply for a pet. He was truly wonderful. At seven, I used to pretend he was my baby, holding him up to my chest in a nursing position.

About a year later, I finally talked about it with my girlfriend at the time, about my grief and guilt, and she looked at me with wonder. “You don’t realize”, she said. “That cat had a wonderful life with you.”

At the animal hospital, I asked for an envelope with a bit of his fur, and a whisker. It’s gone. I don’t know where it is, and it makes me sad.

It sounds like Lavender had a beautiful life with you and I’m so glad he had you to grow up with. It sounds like your family was grieving, too, and I’m sorry that they took it out on you or made you feel like you’d done something wrong. It’s hard not to feel guilty for not doing more for them or noticing sooner or spending enough time with them. I struggle with it, too. But I try to take comfort in knowing that all my pets have had a wonderful life with a warm home and food and a family and that is a lot more than a lot of animals get to have. Your girlfriend is right. Keep carrying Lavender in your heart!

<3 thank you.

It’s been 29 days since I had to say goodbye to my babycat.for eight years, he was my sweet, sweet heart with silly ears. My partner also knew that our relationship was older and deeper than mine with her and has been so kind and supportive.

The last six months have been vet visits and medications and guilt and hope and sadness. Then he stopped eating, and it was time. Every day I miss him. Thank you for this.

Sending you <3. It sounds like you did everything you could and gave him a beautiful life.

There were just enough cute critter pics in this to keep my heart from exploding

Phew. I’m glad for that.

Thank you for this… I still get sad and wonder about what I could have done differently for a pet a few years ago. This helped ease it a little <3

I’m sure you did what you could. These decisions are always so imperfect–if only they could just tell us what they want and need. I am glad it helped a little. <3 <3

Hi Kaelyn! I literally can’t read this because just no, not possible, pet stuff gets me so hard, but I still wanted to send you many hugs ♥♥♥♥♥

Oh my god, I didn’t mean that in the way it sounded. Pet stuff gets me so BAD. So bad. Christ, I’m sorry

Thanks, @queergirl! I got what your meant the first time. :) And yeah, trigger warning that it’s a pretty emotionally intense read if you love animals. Totally understand!

this hit me right in the gut. my first cat zero had to be put down very suddenly about ten years ago when he was suddenly paralyzed by a rare heart defect.. he was only about six (the date stamp on this photo is not accurate, whatever).

still miss him and the very sweet little dog i was raised with, who hung on until the ripe old age of 16. it sounds like you gave your rabbit a wonderful life, and she knew she could rely on you and waffle until the very end.

i never trust people who weren’t raised with pets.

Zero is so pretty! I’m so sorry he left you so early. Thanks for sharing about your childhood pets. People who don’t bond with animals are a hard, “No,” for me. I could never date someone who doesn’t love animals. It just wouldn’t work.

Thank you for this. I’m sorry for your pain and glad for the years you had with them. Losing my cat tore me to pieces -she knew it was time, there was nothing we could have done, but I wish she hadn’t been frightened near the end.

I think that is one of the hardest parts of treating or deciding to put an animal to sleep–that you can’t speak their language to explain it to them. I wish all my babies could have gone like Kitty did, unafraid and in her own home, but that’s just not possible a lot of the time. More often than not, it’s been hard at the end and frightening for the animal, but I like to think the lifetime of happy experiences and safety makes up for it. And, ultimately, they are at peace.

My mom put my last childhood dog down in November without telling me or giving me a chance to say goodbye. I’d had her since I was fourteen, and I’m still missing her nearly every day. Thank you for this. It helps the pain a bit.

Sending love to you and hoping you have lots of happy memories to comfort you. I’m sure your dog loved you very much, too.

My parents cat died of old age. On his last day a female cat stayed by his side till the very end. The old male cat was picked on by this young female cat since my parents brought her in. She had one bad leg but it didn’t stop her. And he got along with her despite her jumping out and scaring him or doing other stuff. But they got along and she was there when he died.

That’s a really heartwarming story. The caring bonds between animals is really something incredible to witness.

When my bun died (referenced above) the family cat (who is not the most affectionate of felines, and wasn’t a huge fan of the bun) curled up next to bun and stayed with him. She didn’t leave his side for over 12 hrs. We humans didn’t know how sick bun was until we realized that BooKitty wasn’t leaving his side. She knew, and she didn’t want him to be alone.

I will never get over that.

Cats, bunnies, and the rest of animalkind: amazing.

Oh, gosh. That’s so sweet.

I already commented, but I think my favorite thing about articles where people talk about how much they love their pets is that the comments are always people telling similar stories and everyone cries together because even if they weren’t human they made us feeling enormous love for another living creature.

If you ever feel like a bad person and all these stories are making you cry, remember that crying means you have a very deep kind of empathy that makes the world a better place.

What a lovely article. I have been avoiding reading it all day, but am glad that I did. I recently lost one of my guinea pigs, so the topic was fresh on my mind. She was six and a half, so had a nice long guinea pig life, but still. Her sister has been taking it especially hard and has barely left her little wooden house. In the past few days she has ventured out more so I have some hope. They were separated for several years before being reunited and after that were almost literally inseparable, frequently touching and cuddling with one another. All this to say, I’m sorry for your loss and wish the best to you and all of your furchildren.

I’m so sorry to hear that, @nosidam. We had a bonded pair of wiggle pigs and when one of them died unexpectedly at a young-ish age, it was really hard on her sister. They really do get depressed. It was so sad to watch her grieve.

She was still pretty young and had a long life ahead of her, so we ultimately ended up adopting another female pig and bonding them (quite a process). It vastly improved her happiness level, but it wasn’t the same bond she had with her sister. She passed recently and the new pig friend actually seems OK with being an solo pig.

It really is hard, for us and for them! I’m so sorry for your loss and I hope you and your little pig feel better soon. <3 <3 <3

As I write this, 3 kittens are roaring around my loungeroom, playing and annoying each other. Occasionally one will jump up on my lap and ask for a belly rub, or attempt to sit on the keyboard.

What makes the triplets different is that they are my foster kittens. Our local animal welfare group has a no-kill policy; what with the warm weather, there’s been a lot of kittens this year that have been surrendered/dumped etc.

Thus I have 2 brothers – the “ginger ninjas” and a gorgeous tortie girl, who will live with me until their forever home comes along.

I also have my soul-mate, a gorgeous grey tortie girl (adopted from the same agency) who is my absolute everything. We share my autostraddle account because there aren’t pet ones yet.

In purchasing 38 tins of cat food last night, I did wonder if I was slightly crazy cat lady-ish. And then I immediately dismissed this, because oh hell if I am, that’s a wonderful thing to be.

For all the cats I have loved and lost, I wouldn’t change a single moment.

Thankyou KaeLyn for these lovely words, especially the ones about imprinting and whispering our fears in the dark. xx

Thank you for the life-saving and incredible work you do! <3 to all the furkids you’ve loved and saved!

I adore rabbits and this had me in tears. I’m sorry for your loss.

Bunnies are the best! Who’s that cutie in your pic?

Oh man this hit me hard. Saying goodbye to pets is one of the hardest things in life (but I think in a way it’s a fair trade-off for all the joy they bring into our lives). I’ve just been worried about my pup and my grumpy old man cat who are both 14(ish). The pup is still as stubborn as ever, and it looks like she’s cancer-free for the time being, so we can enjoy her stubbornness for awhile more. Because wow, I just haven’t met an animal as stubborn as her, whether it’s about whether she is allowed to bring whatever rock she’s found to play with in the house or being alive in general. We’ve had two serious conversations about this already in her life–the first before she was diagnosed with myasthemia gravis, when we didn’t know what was wrong with her at not-quite-2, but she was unable to keep food down. And then a second time when she herniated a disc in her back at 6 or 7 from jumping off the boat or off the dock or off the brakewall one too many times and her hind legs stopped working. I’m glad we get more time with her. But my grumpy old man isn’t doing well. He’s lost a frightening amount of weight in the past 6ish months and has lost a lot of his appetite. He’s crankier than he used to be, but also friendlier, in that he just wants to lay on top of you whenever you’re sitting down and he will LOUDLY complain if you move or get up.

I also remember my first cat, Uptree (I was 3, okay, and we found him up a tree) who adopted us far more than we adopted him. He was a big, floofy stray who probably had some Maine Coon in him because of his size and coloration, and if ever a domestic cat embodied Mufasa, it was him. He was a hunter (we rarely appreciated his presents) and a king ruling the household–including the dog once we got her; had he not been around I don’t think she would have respected cats as much as she does. He was moderately overweight most of the time he was with us because of how he would gorge himself on the food–we think he was 8-10 when he found us, and he had not had a kind time of things before us, so it was understandable that he had a thing about food. Unfortunately, his weight issues led to diabetes. He stuck around for a really long time. Sometimes I wonder if we selfishly kept him too long because we didn’t want to see him go, but once he needed twice daily insulin injections, we knew that it was time because he wouldn’t tolerate that and he really wasn’t doing well at all. We think he was around 18-20, a truly old and respected king. I don’t miss him most of the time almost 10 years later, except on winding nights when the screens rattle in the windows and I look to see if he’s there, waiting to be let in because he would always bat at the screen to let us know.

It was an easier decision to make with Trouble, the cat who lived up to his name, when he had kidney failure. Trouble never was the smartest cat, nor was he a leader (he had been second while Uptree was around, briefly and bafflingly first when it was him and the dog he never got used to and the still-mostly-feral Black Cloud who we raised from a kitten who avoided humans as much as possible, and then promptly usurped when Paw (current resident grumpy old man) entered the picture). Trouble survived two run-ins with cars, making him probably the luckiest cat ever, but considering he was an indoor cat who got outside unsupervised less than 10 times ever in his life, also the unluckiest cat. But he was a trooper, surviving a broken shoulder the first time, and then a prolonged, dramatic trauma of nerve damage, self-amputation, several surgical amputations, and then addiction to the pain medication when his tail got run over the second time. The whole ordeal is known as “The Troubled Tale of Trouble’s Tail”, if anyone’s interested in the full gory details. I mostly miss seeing him and Paw curled up together in the one cat tower because they were such great buds and Paw is lonely without Trouble (though after many years, he’s mostly decided my other cat is acceptable. Barely).

It was probably hardest to say goodbye to Spot because we had no choice in the matter and should have gotten so many more years with him, if he hadn’t been killed by a car. Spot came into our lives entirely by accident–he was small and the exact same shade of gray as Trouble, and we thought that Spot was Trouble, escaped in the crowd of people we had had over for a 3rd of July party. It wasn’t until the next morning when we found two gray cats inside that we realized that one of them was slightly blockier and had a single white spot on it’s throat. We tried to return Spot outside, in case there was someone missing him, but he refused to leave and adopted us. Spot entered our lives as the fourth cat, where the other three liked each other quite a lot, and saw him as an interloper. I had worried he was lonely, but it was also a pretty sweet deal because it meant that he wanted to spend more time with me. He also had this sixth sense to know when I was upset or crying because he always found his way to my lap to sit on and be pet until I felt better. I miss that a lot sometimes, because I haven’t had an animal since who is so good at that (Win comes close a lot of the time though).

I’ll leave things on a happier note and talk about my other current cat, who is middle-aged and healthy and SUCH a shit. My mom is her favorite person to mess with, usually by trying to escape the confines of the house. Win is not an outdoor cat, she knows this, she just wants to lay on the pavement of the sidewalks and roll around for a bit. She’ll only come when I call. Every day after supper, she comes over to us at the table because it is Time For Attention and jumps on my lap. The rest of the time, pretty much the only time she wants attention is if she has mats starting in her long fur, in which case it’s up to me to get them out. She’s incredibly jealous and cannot stand if you start petting the dog or Paw instead of her. She squeaks instead of meowing most of the time. And she is a licker to people she likes. She hates other cats (though Paw is acceptable) and spent most of the two weeks that I was catsitting for my friends holed up under various pieces of furniture growling. She likes to cuddle with the dog more than any human. When I’d come home for breaks from college, she’d usually spend a few days avoiding me (like literally leaving the room whenever I entered it) to make sure I knew she was mad at me. The only other way to summon her is to wear clean clothes that have minimal pet fur on them, and since she’s white and brown and black, at least one color is going to show up on your clothes no matter what color you’re wearing, and she thinks it’s obscene that you could go around without her fur on you. And she’s such a queen and has such regal bearing–she wants to chase the laser pointer or the string or whatever cat toy, but you can’t notice her doing that because it’s undignified and if she knows that you’re watching her do those things, she’ll stop and walk away (but not TOO far away because she wants to play SO BAD). And her eyes are the prettiest shade of green I’ve ever seen.

Hollis, all of this is just delightful. I genuinely laughed and smiled through the whole tale. Thankyou for sharing.

This was such fun to read, even the sad parts. They are such unique and weird little family members, each one of them. I’m glad they got to be a part of your life and vice versa.

We put our 20 year old cat to sleep two days ago, and my gf is bereft – it’s her presence she misses most – her lying on the porch when we get home from work, jumping on the bed in the middle of the night and freaking us out, howling the neighbourhood down at 4am just because she could – we miss her horribly. Saying goodbye is the hardest thing about having pets.

I’m so, so sorry for you loss. Saying goodbye after all those years is awful. xx

I’m so sorry, @jessem. Twenty years is a long and wonderful life. I’m glad she spent much of it with you. Missing them is the worst. It feels like there’s an empty spot in your life every time you are reminded they aren’t there. Sending you and your GF <3.

I never comment online, but had to break my rule to comment on this. I also made the mistake of reading this in my office at the end of the work day, so everyone leaving for the day could see me trying not to sob at my desk.

I’ve also had free range rabbits throughout the years, but my most beloved rabbit Chico passed away last August. While I always get sad when a pet passes (I cried over my hamster dying when I was 28 years old), Chico was an acute loss, as he was my best friend and constant through cross-state moves, relationships, and jobs. It was also sudden. One morning he was fine, the next he wasn’t. It turned out his body was riddled with cancer, but you couldn’t feel the tiny tumors underneath all his fur until one got too big for us to notice and after that it was too late. I couldn’t sit with him when they actually put him down because I was too upset, and it’s still a decision I regret.

Essentially, this article just really hit home for me and it’s beautifully written. I was always the crazy bunny lady who people didn’t realize why I was so upset after he died, so it’s always nice to find other people that love their bunns as integral members of your family.

Waffle says I should have put a disclaimer on this post that it would cause “ugly crying.” Sorry about that!

Chico sounds like a wonderful best friend. I’m so glad he got to be your buddy and you got to be his. They are SO good at hiding it when they are ill. It’s awful when it happens seemingly overnight like that. I’m sure you did everything for him that you possibly could have. From one bun parent to another, <3 <3.

KaeLyn, this was so beautiful. Thank you for sharing this. I am saving it now for the day that will inevitably come when I need it. Thank you for helping me have the strength to bear it when the time comes

<3 <3

Oh. This was so sad to read. I recently went through this with my then-significant-other; his cat was getting sick, not eating and getting weak, and we didn’t know why, but he’d booked a vacation and I told him to go. I cat sat for 2 days before I had to take her in to the vet, and 2 days later I got horrible news. She wasn’t my cat but we’d bonded so much. Her owner booked an early flight back. I took her in for a transfusion and when she came back she climbed all over me, ate all the food, let me pet her for hours. I was drained from crying all week; when her owner came back and I then left for my own vacation, he told me i saved her life. If only I had; a few weeks later she was downhill again and I spent an evening with them feeding her treats and giving her affection. I played with her sister; they were litter mates, and after all the weight loss the size difference was almost comical (her sister is very overweight). When she was too weak to jump onto the bed, I could pull her up with one hand. The next morning we went to the vet and came back with an empty carrier. We then had to leave the sister alone all day, probably confused and lonely.

We had the same questions about grief. Did her sister mourn for her like we did? One night when I slept over, in the middle of the night I realized that the affectionate one was not up on the bed with us and I woke my significant other up to cry on his chest. We just lay there for a while; I had no idea what the other cat was doing or if she understood.

It’s hard making decisions for another living being. Life is so delicate; and the question of when to give up on it is so hard. I know that when I have the flu I feel so miserable I want to die, but I know I’ll get better; what if I didn’t know that for sure? What if I wasn’t gonna get better? How would an animal feel in this situation, and would they want humans to make the call for them?

I realize I told this all from my perspective; her owner is a terrific cat-parent and spent far more time with her than I did, obviously. He had to make the incredibly difficult decision all by himself, and I wish I had been better able to help him make the call. You’re not supposed to pick favorites with siblings, but she was his favorite, probably for the very reason you mentioned pets being important to their humans: they are above the petty human-ness we all struggle against, they don’t judge us, and they will accept us as long as we feed them. It’s far easier to put one’s trust in a pet than anyone else.

I’ve never even had pets and I still cried reading this.

I wasn’t ready to cry from reading this, how much you care for your pets makes me so happy tho. It’s so good to just be able to love and care for someone and make their lives better.

My mother called me this last easter morning. They had headed home from church, and found my dog on the side of the road in our yard. Somebody had hit my dog, the one I’d had since I was 4. My doggie who I raised and took care and fed and bathed even though I ended up just as soaked as him by the end. I took him on walks and runs played fetch, taught him how to give a high five (the only trick he ever learned) I’ll always miss my Maxie, and remember the good times with him.

Thank you for sharing your experience of losing your fur baby with us.

I’m so sorry to hear about your loss of your family member and doggie best friend, Asher. It’s so hard, but I hope your happy memories are bringing you comfort. <3