So you’ve read the Don’t Ask Don’t Tell survey (which can be downloaded here), and you’ve felt vaguely negative about it but didn’t have the words to explain why. It’s alright; I felt the same way! Luckily, I had a great Research Methods teacher (holler Professor Kiter-Edwards) and a text book by one Earl Babbie that is honestly one of the most enjoyable text books I’ve ever had to read.

We’re going to focus on a few of the biggest problems going on with the survey because we’re smart people, obviously, but we don’t want to be showoffs.

Full disclaimer: I’m only 3/4 of the way through my degree in sociology, which means that I’m ignorant of a full quarter of the information that I should know. Maybe you know more than me. If you do: spread the wealth! Let’s talk about what works and what doesn’t.

Issue Number One:

WTF is the research question?

Surveys can be done for three main reasons: exploration, description, or explanation. If you’re exploring, you’re saying “we’re not really sure what’s going on so we’re going to find out some stuff so that we’re not bumbling fools.” If you’re describing, you’re asking what. And if you’re explaining, your research question is going to be about why. According to Geoff Morrell, pentagon spokesman extraordinaire, they are “not playing games here, we’re trying to figure out what the attitudes of our force are, what the potential problems are with repeal.” In other words, they’re exploring.

Exploratory research is usually done with subjects that no one knows anything about. If you want to know how many times a year the average person eats Nutella or if aliens might exist, you would do exploratory research. The problem with this approach to the DADT problem is that exploratory research doesn’t really provide any answers. It’s meant to act as a primary indication of how things might be and to be a stepping stone for further research, but the issue here is that the military seems to be viewing it as comprehensive.

What’s most problematic is that there doesn’t appear to be any sense of direction. Are they planning on using this information to stage more in-depth research about why people feel the way they feel, or are they just going to throw out the House’s bill if enough people say that they wouldn’t want a gay tent-mate?

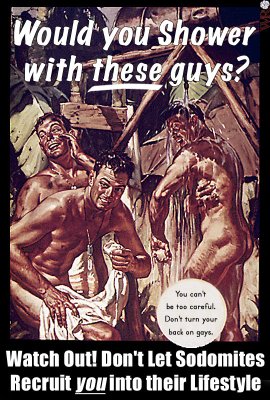

The survey asks how people feel about gay shower buddies and lesbian neighbors but neglects to ask why people feel the way they do. This isn’t a survey flaw as much as it is an indication of the general attitude of the country. To probe into why people are homophobic would be to admit that there’s nothing wrong with gay people and that’s something that the government’s not ready to do.

It’s important to point out that while we’re all quick to find fault with the survey, it could help us in the end. If the results are supportive, it just might mean that all that exploration was worthwhile. In defense of the idea that gays serving openly in the army ain’t no thang, I’d like to present you with a choice quotation from the beacon of truth, “Given its fundamental nature, exploratory research often concludes that a perceived problem does not actually exist.” Bam, roasted.

Glaring Issue Number Two:

Validity and reliability

Let’s talk about validity and reliability and the difference between the two. Validity means that the results accurately describe what is being studied, while reliability means that the measures used will give consistent results in different populations and at different times. To illustrate:

Are you still with me? Great! Now let’s talk about the types of validity. Did you know that this is on the first page of results that you get when typing “face validity” into Google images?

Anyway, face validity means that the instrument used (which in this case is the survey) makes sense to the population to whom it is given. What does this mean to you? Another vocab word that I’m going to throw at you is content validity, which means that the survey is a good measure of the concept being studied. Keep these two guys in mind because we’re going to come back to them when we get to survey design.

My major complaint in this department is with reliability. One of the ways to guarantee reliable responses is to used established measures — instruments that have already been used. I know it sounds old fashioned and conservative to want them to use a tried and true method, but seriously can I get a Guttman scale up in here?

A Guttman scale is a series of questions that works on the idea that if you identify positively with items that come later on the list, you should logically be copacetic with those that came before. One of the most famous examples of a Guttman scale is the Bogardus social distance scale, which goes like this:

Please place a check by all the statement with which you agree:

[ ] It is alright for people to immigrate to this country.

[ ] It is alright for people to immigrate to this state.

[ ] It is alright for people to immigrate to this city.

[ ] It is alright for people to immigrate and live on this street.

[ ] It is alright for people to immigrate and live next door.

Guttman scales are great because they help researchers compiling the data to quickly find the relevant data. If someone says that they’re comfortable with immigrants living on their street but uncomfortable with immigrants living in their state, you know that they’re either not paying attention, not making sense, or insane — you can throw their response to this question out. Another perk is that they’re straightforward and don’t leave a lot of room for interpretation for the researcher.

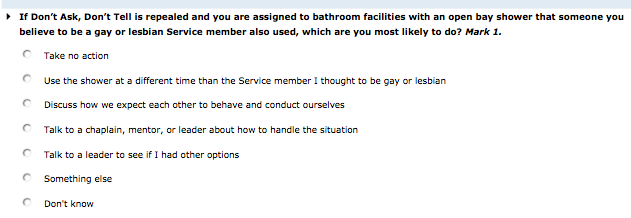

Por ejemplo, here’s a question from the actual survey:

But what do those answers mean? If someone says they’re going to take no action, does it mean that they’re down with gays or that they’re just too afraid to do something? Maybe they discuss how they expect others to behave with every new service member or always shower by himself. If they talk to a mentor, does that mean that they’re simple struggling with accepting their new gay comrade and trying to work to accept them or does it mean that they’re trying to pray away the gay together? The only thing we really learn from these answers is who is a tattletale, who keeps to herself, and who’s bossy.

This survey could have had a similar scale that went something like:

[ ] It is alright for gays and lesbians to serve in the military

[ ] It is alright for gays and lesbian to serve in my branch

[ ] It is alright for gays and lesbians to serve in my division

[ ] It is alright for gays and lesbians to share my tent or room

[ ] …

But instead we have all this nonsense about talking to chaplains if you have to poo near a man who you think might be gay jumbled up with other questions about fulfilling a mission during combat. My head is going to explode, so let’s just move along to the next section, shall we?

So Shiny It’s Blinding Us Issue(s) Number Three:

Survey construction

There’s a lot going on here so let’s look at it little bits at a time.

+ Choose appropriate questions

Know what one the most unclear type of survey question is? Close-ended questions. Wanna take a stab at what type of question appears most often on the survey? If you guessed close-ended questions, you’re already better at social research than most of the people at Westat, that research firm that’s being paid $4.5 million to conduct the survey.

Close-ended questions are items that already have a group of answers that you have to choose from. Besides forcing the researcher to decide what the data means (like we saw in the bathroom question), close-ended questions are often difficult to word so that the options are exhaustive and mutually exclusive. The exhaustion issue is taken care of in some questions with the addition of a “something else” option along with a box to fill in, but mutual exclusivity doesn’t appear to be at the top of their list of important things. They’re a big fan of the “check-up-to-three”-style of response, which isn’t necessarily a fallacy but does reduce the reliability of the survey.

+ Respondents must be willing to answer

In the U.S., we tend to be bigger fans of rationality, which is often equated with being moderate. If someone feels like they might be in a minority when selecting a response, they may choose fitting in over honesty. Intern Emily wondered exactly how the survey was being administered, which is a totally valid concern. The pressure to remain in the majority might be even stronger if you’re filling out a survey while others are around.

+ Questions should be relevant

Beside giving me titles for all these headings, Mr. Babbie says “when attitudes are requested on a topic that few respondents have thought about or really care about, the results are not likely to be useful.” This goes back to the question of how much troops really care if they’re serving with gays and lesbians. If you’re in a combat zone, how often are you thinking about whether the girl next to you likes girls or boys. If the answer is a lot, and you’re a guy, please stop watching bad porn and get your head in the game. You’re at war.

+ Short items are best

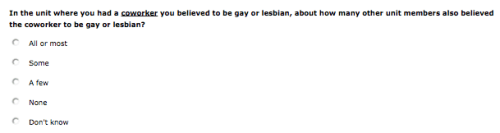

There are a lot of things that this survey is, but short is not one of them. Just for fun, let’s say that there’s nothing wrong with the questions, the survey’s just too lengthy. Potential respondents might be daunted by the 32 page document and decide not to take it at all. Here’s an idea, how about about combining these three questions into one question with three parts?:

+ Avoid biased items

Remember five minutes ago when we discussed validity? It’s time to use your knowledge of face validity to look at the language used.

What a bad idea. If you haven’t yet, just read this study and take a moment to think about how you might think people would respond differently to words like “assistance to poor” and “welfare,” or “dealing with drug addiction” and “rehab.” As far as biased language goes, there’s also the issue of wording used that suggests that queerness is something that must be tolerated, which Riese talked about a few days ago. It’s worth nothing that according to the Riddle homophobia scale, another famous sociological scale, the survey’s attitude toward gays and lesbians falls under the “homophobic” category.

And so there you have it. I feel happy that I’ve put my college education to good use before even graduating, which I hear is rare these days. So what happens now? Towleroad has a great round-up of some of the reactions to the survey, including the Pentagon defending it, and Nate Silver of fivethirtyeight.com saying that that “parts of it are completely useless.”

And so there you have it. I feel happy that I’ve put my college education to good use before even graduating, which I hear is rare these days. So what happens now? Towleroad has a great round-up of some of the reactions to the survey, including the Pentagon defending it, and Nate Silver of fivethirtyeight.com saying that that “parts of it are completely useless.”

Let’s end on this note from Rob Smith, a gay Iraq War Veteran, mocking the survey:

“The way some of the survey questions are structured is enough to make one think that its creators are as obsessed with gay sexuality as those who practice it regularly. In fact, the survey really hit the nail on the head with the whole shower thing. I wasn’t able to shower for the first three weeks of my tour in Iraq, and what do you think I was looking forward to the most when I finally got the opportunity to take one? Was it perhaps the opportunity to remove the thick film of gruel that encased my skin no matter how many times I wiped myself down with the wet naps provided with our meals? If you thought that, you were wrong. It was obviously the opportunity to sneak a peek at other soldiers in the showers, soldiers who were equally if not more as disgusting as me at that point. Sexy, right? I sure thought so, but imagine my SHOCK that there were private showers! In Iraq! It was almost enough to make me want to give my two weeks’ notice right then and there.”

Equality California wants you to petition Defense Secretary Robert Gates, requesting that a more fair, unbiased survey be given to servicemen and women. EC’s Government Affairs Director, Mario Guerrero, had this to say:

The survey is insulting, one-sided, and designed to illicit a negative response.

As a veteran of the U.S. Marine Corps, I know the effects of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell all too well. My sexual orientation was not an issue for over six years until I was outed. The military’s Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy prevented me from joining my fellow marines in Bagdad. Unfortunately, they were not able to rely on my training and experience.

Time is of the essence. The Senate could vote on the repeal as early as this week. And a federal court challenge starts today, brought by Log Cabin Republicans.

It’s not really a petition so much as it’s a form letter, which means all you have to do is fill in some fields and hit send. Pass it on, little queerios!

Comments

i wish they* would read this and realize how ridiculous this survey is.

*”they” can be the military, obama, or even oprah, everyone listens to her!

Laura… you’re amazing. That’s all I got right now at this moment.

The sharing showers argument was I swear to God the response I got from my asshole Senator well before this survey made its rounds.

And fear of showering with gays has got to be one of the dumbest factors to consider since you will be living with/showering with gays and lesbians under DADT already.

Maybe we should’ve framed the campaign to overturn DADT as “Hey, soldiers and sailors! Wouldn’t you like to know who The Gays are so you can plan to shower at another time?”

Thanks for the great points, Laura. Definitely passing this on.

This is not a helpful thing to say, but if the whole world took communal showers, and was split into timed hetero bathing sessions and queer bathing sessions I would not be unhappy.

Well everyone knows gayness is contagious. And in warm, damp environments like communal showers, it spreads best. Symptoms include itchy, scaly, or flaky skin on the feet.

Oh wait, that’s athlete’s foot.

Whiny congressmen needs to suck it up and grow some security in his gender and sexuality.

as someone who had to learn more things about research methodology than i would have cared to for my degree/line of work, i give you two fists for this.

THE SCIENTIFIC METHOD EXISTS FOR A REASON.

i can’t even believe this is really happening.

I’d like to propose an official name change:

Internet Hot Laura to Intern Hot and Smart Laura.

Great post. Submit this as a paper and include the pictures and you get an A+ for awesome.

you make me blush.

JOB WELL DONE! I feel like I’m in summer school. I feel a tad smarter now, thanks.

Go Laura!! :D

I just forwarded this article to my social work research professor because I thought he’d find it interesting and guess what?

He said that the article was well done and that he’ll incorporate it into class tomorrow.

Autostraddle=college professor approved

jamie this just made my day.

So my teacher did indeed present the article today and work it into our current events discussion.

Best part of the discussion?…

Hearing the word “Autostraddle” about 30 times in class

That survey is absolutely ludicrous, and they’re being paid 4.5 million?? Money which could be better spent elsewhere.

You know what, they’d be better off just asking ‘Paul the World Cup predicting Octopus’ what the outcome should be.

Better still, get you guys to do it.

P.s, Laura, you definitely deserve a tonne of extra credit for this post from your Uni – it’s excellent!

i feel smarter and which all my textbooks were written like this.

So, I agree with most of your comments (Brava!) but I’m down with Nate Silver on this one.

I think the primary flaw of this survey isn’t methodology of individual questions, but rather general scope, to which you allude. Having had some brief contact with the Joint Forces Command through work and having lots of defense industry friends, I think the military is legitimately worried about implementation of DADT – not so much because they are going to fight tooth and nail against it, but more because they know it’s completely INEVITABLE and are misguidedly attempting to understand how to manage it.

Quite frankly, the military’s deep worry is that their ranks are full of homophobes, and that said homophobes would leave the military or otherwise go batshit once DADT is rolled back. Definitely wouldn’t happen that way in the U.S. Navy, but that’s another story :) I believe the purpose of this survey is to gauge that impact on unit cohesion and the practical aspects of making sure people serve with each other – at its core, the military is about psychological collectivism, the closing of ranks, and enormous sacrifice of personal space and some big individual civil liberties in order to effectively attain its objectives against the enemy. (Whether the civilian guidance under the Bush years pursued the right objectives and right enemies is a separate and well-trod discussion.) Small, tangential things unrelated to combat/defense but that can very much affect combat performance, like whether soldiers dine together or alone, can make a huge impact. (Hence the huge importance of the common mess hall and scheduled meal times for coordinating units.)

One of the questions you highlight – about using the shower and likely reaction – is not necessarily best replaced with a Guttman scale. (And not to be a huge nitpicky asshole, but your example Guttman scale doesn’t necessarily relate well to physical space – the corollary units would be lead my unit / serve in my unit / etc. although a good separate one could definitely refer to the physical living space you define.) My guess is that it’s a pragmatic question on some levels – if there are going to be an influx of PFCs going to their sergeants with questions about how to coexist harmoniously with openly gay colleagues, the Army better effing scale down some really strong training to everyone.

Even though the branches did not conduct these kinds of surveys in response to desegregation in 1948 or the incorporation of women on ships at sea in 1976, I think it may actually be a good sign that they’re trying to do this now: the military has woken up to the fact that there is this thing called culture and there are legitimate ways to “measure” it. I’ve looked at the full survey contents on scribd out of my nerdy interest and I think there will be some really useful data points from pp. 1-10, 19-32.

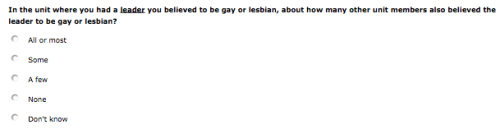

However, totally agreed with you and Silver that this is a stupidly flawed survey for a good chunk of the questions – it is more or less useless, as well as rather offensive, to ask servicemembers to spit out their gaydar (or paranoid homophobia) about their peers and leaders, potentially outing them under DADT. (The anonymity/privacy issues with this survey, beyond minority bias, are RIDICULOUS in terms of the potential for outing oneself / one’s unit leader or peers, so I think the results will be neither valid nor reliable, as you say.)

The main problem is that it’s clearly written with an Insider/Outsider perspective, with the Other clearly defined as the big, bad “HOMOSEXUAL”, as you say. While there are probably legitimate concerns about unit cohesion post-DADT, there is an equally legitimate concern about unit cohesion right now with DADT. There are many servicemembers currently dealing with (very real) deficits in individual morale due to DADT, and I am certain that this impacts unit cohesion: There are reams of survey data and qualitative accounts on how this degraded leadership in corporate boardrooms and other workplaces, and the military is no different.

By failing to issue a third-party conducted and fully anonymous survey that explicitly asks LGBT servicemembers about the real challenges they face and extra sacrifices they have had to make, DoD has really failed to address the most important audience for DADT. One hopes this huge media firestorm will convince them to do that so that they can and should measure that data point when they consider all these others.

When did the military start caring about the soldiers feelings? If the brass says you should be ok with the gays you better be.

The brass also says soldiers aren’t supposed to commit adultery on their partners. Seriously, this is a court-martial liable offense in the military. But the fact is

I definitely don’t mean to morally equate homosexuality with adultery. I think I’m actually meaning more to equate homophobia with adultery – a desirable behavior of honorable moral conduct for a soldier, but falling in a non-combat domain. In both circumstances, military policy can say one thing but these things can and will break down where it’s not practical to enforce. Most non-violent, non-classified-information acts fall in this group.

Imagine the following nightmare scenario if the DADT repeal is executed poorly: Certain units or even branches become known as “gay-friendly” vs. “homophobic”. Parts of the military start self-segregating (more so than they do already). Certain units have communication breakdowns and personnel mismatches because of this simple fact, when it could’ve prevented if an appropriate prevention and response policy had been communicated early on.

Of course, we know that communication breakdowns and personnel mismatches, and recruitment failures, etc. already occur because DADT already exists. If the existing survey didn’t have such a homophobic bias to start with, it could be incredibly useful to identify trouble spots – e.g. certain platoons, deployment sites, bases, etc. that are the most homophobic, so that top brass can move aggressively early on to emphasize the national priority of repealing DADT and a zero tolerance policy for homophobia.

To clarify, since I’m a failure at late-night multitasking when I’m trying to distract myself from Powerpoint:

fact is adultery happens among military personnel all the damn time, and it is rarely if ever prosecuted even though a military spouse can legitimately bring a suit and potentially get an ex dishonorably discharged or worse if they have good evidence of the cheating.

AND

adultery and homophobia as UNdesirable behaviors for an “honorably serving” soldier.

Thanks for being smart so I can feel smart too. This was great. And your little Guttman scale rewrite is brilliant. Hi, why couldn’t the survey be that simple? Thanks.

Let’s not forget the history of “Don’t ask, Don’t tell.” Originally it was lauded as a huge step in the right direction. You must remember that before DADT if you were suspected of being gay, lesbian, bi-sexual, or anything other than straight, the military could and would criminalize you.

Here is a prime example. While I was in training, yes I’m a veteran, there happened to be the first few women allowed in “combat training”. A few of the girls, tried to relieve the stress one evening. Since they were all in the shower and touching, fifteen of them were branded as lesbian. They were charged with conduct unbecoming, arrested, prosecuted, and jailed for thirty days; prior receiving their dishonorable discharges then sent packing. (The Military paid for a bus ticket to the nearest city and abandoned them.)

It didn’t matter that three of them were married or had children. When I trained, it would be amazing that out of 45 to start training, maybe 20 would graduate. Don’t get me started on the authorized harassment. It was worse if the solider happened to be male and were outed as gay.

They were usually beaten, stripped and tied to the pillion in front of the unit before being ran out of town. Then the command would charge them with AWOL. Many couldn’t take it and attempted suicide. Let‘s be honest, We are talking about people who had the means. They were being trained on how to kill the quickest and most effective way. If you were to look at the training accidents and deaths… you might get a better picture. Yes the command knew what was happening and turned a blind eye to it. To them it was the same as getting rid of vermin and sub-standard troops.

Remember that the military is run by a small group of people who are completely out of touch with society. In my day, it was called being in your military mind. For those of you that don’t know…. Take a peek at the UCMJ. It took me years to come to grips with what I experienced in my six years of service. Yes, I’m proud of my service, Yes, I caught a bullet for my country. Yes, I support our troops. I just thought the history lesson might do some good for those who don’t realize the alternative.

If they repeal DADT, don’t expect that they will just automatically accept openly Lesbian, Bi, Gay, Transgendered, recruits. They will most likely just revert to the rules of engagement that were in effect prior to DADT.

“They will most likely just revert to the rules of engagement that were in effect prior to DADT.”

Teri, that is an excellent and horrifying thought. I’ve been wondering for a while now that even though the administration has been saying, “we’re looking at HOW to repeal DADT, not IF we will repeal it,” since this whole thing is dependent upon what the DoD comes up with, what if they say, we need more time, or we can’t agree on the implementation? Does that mean that DADT is repealed and simply reverting to the old way, since that is the previous rule on the book? Or what if they just say, “the study was inconclusive, so we’re just going to keep it the same.”

I guess I am going to try to stay positive and hope that even though the study is totally biased and flawed, the results will be positive and in line with the average american.

Also: I am sorry that happened to you Teri and thank you for your service:)

Since I’m gay, I’m also a sociology major (well. non-practicing, at the moment. IRRELEVANT.)

and OH MY GOD I THINK I LOVE YOU, LAURA.

This is PERF.

I think one of my main beefs with this survey is that it’s asking these individuals to determine not only how their colleagues feel but what they do with those feelings.

For instance: It asks how THE BELIEF of a colleague’s homosexuality affected the unit (and other reconstructions of this question). Okay. So let’s say the belief “negatively” affected the unit. But it doesn’t explore that maybe the negativity is from the fact that he/she is having to keep this under wraps.

That was poorly worded. Try again.

It doesn’t address the possibility that being gay in the military might not be such a BFD and the only thing causing all the drama is the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell part.

My brain is tuckered out from this. A+.

So this article is amazing. And the issue itself makes me extremely angry. I think the biggest problem is the possible answers to the question. They’re not specific enough. My thoughts are pretty much identical to this paragraph here:

“But what do those answers mean? If someone says they’re going to take no action, does it mean that they’re down with gays or that they’re just too afraid to do something? Maybe they discuss how they expect others to behave with every new service member or always shower by himself. If they talk to a mentor, does that mean that they’re simple struggling with accepting their new gay comrade and trying to work to accept them or does it mean that they’re trying to pray away the gay together? The only thing we really learn from these answers is who is a tattletale, who keeps to herself, and who’s bossy.”

So thankyou for putting the angry jumbled thoughts in my head into a perfectly written paragraph.

Also, your Guttman scale is brilliant, and if they’d just sent something like that out, it would’ve been so much more helpful. Still could be viewed as slightly homophobic, but helpful for researchers to see exactly where people stand on the issue. And I think that’s all they’re really trying to do.