Welcome to Idol Worship, a biweekly devotional to whoever the fuck I’m into. This is a no-holds-barred lovefest for my favorite celebrities, rebels and biker chicks; women qualify for this column simply by changing my life and/or moving me deeply. This week I’m learning to fly with Amelia Earhart.

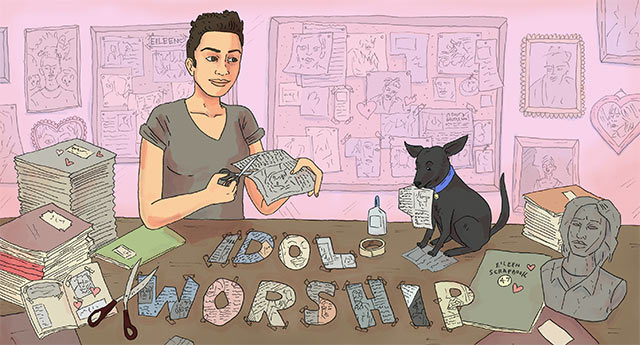

Header by Rory Midhani

I fell asleep Saturday night around 10p.m., probably only a couple of minutes before the tweets started cascading and the noises started being made outside. I woke up at 3:30a.m. to an email from Rachel: “this feels like the least fun or okay day in the world.” I immediately googled “Trayvon Martin.” Then I put my head in my hands and cried. I immediately went to where people might be, where someone might be who could talk to me until everything ceased to make me feel sick: the Internet. I noticed a particular bell hooks quote blowing up on Tumblr:

White supremacy has taught him that all people of color are threats irrespective of their behavior. Capitalism has taught him that, at all costs, his property can and must be protected. Patriarchy has taught him that his masculinity has to be proved by the willingness to conquer fear through aggression; that it would be unmanly to ask questions before taking action. Mass media then brings us the news of this in a newspeak manner that sounds almost jocular and celebratory, as though no tragedy has happened, as though the sacrifice of a young life was necessary to uphold property values and white patriarchal honor. Viewers are encouraged to feel sympathy for the white male home owner who made a mistake. The fact that this mistake led to the violent death of an innocent young man does not register; the narrative is worded in a manner that encourages viewers to identify with the one who made the mistake by doing what we are led to feel we might all do to “protect our property at all costs from any sense of perceived threat.

The entire Internet was eating this quote up, letting it fall from their mouths in big pieces that covered the table. Many of them didn’t realize, however, that the quote appears in the book All About Love: New Visions, which bell hooks published twelve years ago in 2001.

There’s a question I can’t shake: why is it still true?

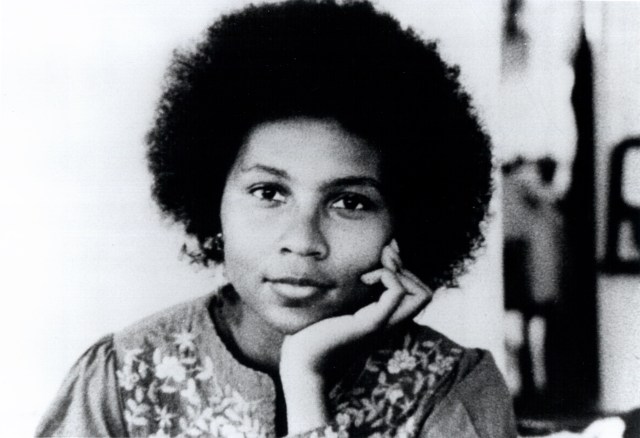

bell hooks was born Gloria Jean Watkins on September 25, 1952, in Kentucky. She was one of seven – with five sisters and one brother – being raised by a custodian father and a stay-at-home mom. She attended segregated schools, but eventually suffered through a shocking integration; all along, she remained a prolific reader and writer who was deeply moved by women’s leadership in spiritual movements.

Watkins came to adopt “bell hooks” as a pseudonym in honor of her grandmother in 1978, when she published her first book: And There We Wept. She chose not to capitalize the name in order to differentiate between the two women and remove the focus of her work from her own narrative. Ain’t I a Woman?: Black Women and Feminism was published in 1981, and would serve to introduce bell hooks to the burgeoning community of feminist theorists and writers as a post-colonial, post-modern mind grappling with issues of race, gender and sex.

bell hooks’ inspirations in her work – which now spans over 30 books – includes Sojourner Truth, Paulo Freire, Gustavo Guitierrez, Erich Fromm, Lorraine Hansberry, Thicht Nhat Hanh, James Baldwin, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr.

As a cultural critic and destructor of the patriarchy, bell hooks’ work often linked issues of sexism and racism, focusing on the intersections of oppression long before the concept was commonplace in the movement for women’s liberation. By stressing that the feminist movement needed to include the broad experiences of black women – and by expanding the scope of understanding patriarchy to include how it affects men of color as well – she has been able to write with clarity on the importance of community-building, solidarity, and social politics. Recently, her work has focused on how loving communities can come to be and how they can overcome hatred and inequalities. bell hooks explained in All About Love:

When love is present the desire to dominate and exercise power cannot rule the day. All the great social movements for freedom and justice in our society have promoted a love ethic. Concern for the collective good of our nation, city or neighbor rooted in the values of love makes us all seek to nurture and protect that good. If all public policy was created in the spirit of love, we would not have to worry about unemployment, homelessness, schools failing to teach children, or addiction.

Although bell hooks has been writing and working in feminism for decades, her concept of an inclusive, diverse, non-patriarchal world that welcomes people of all races, ethnicities, desires and experiences has yet to come to fruition. She continues to play an important role in feminist theory and politics, and helped to shape the modern discourses around building a more inclusive and whole movement. Because of scholars like bell hooks, concepts of race and class have become interwoven with feminist activism and inextricable from its ultimate goals; because of that defining growth in the movement it has ultimately come to liberate more people. Recognizing internal and overlapping forms of discrimination, and looking for them within ourselves and then among our external world, is now a commonplace part of being a feminist thinker. Sympathizing with the contrasting experiences of oppressed communities and recognizing the systemic inequities in our power systems is no longer a second thought in this movement.

bell hooks’ feminism is, in many ways, my feminism: intersectional and self-aware. I like to think that for five years I have been very much a part of that bringing that concept alive in my own life and in the larger movement, and have put good effort into working to make it happen. But the Trayvon Martin ruling broke my heart. What makes us so full of contempt, so scared of one another, so unwilling to be whole and human and compassionate and loving? And how can those of us invested in social justice merely “keep going,” despite the frustrations of watching an entire culture oppose the idea that we all hold common a singular human experience?

After the Trayvon Martin ruling it was hard not to feel hopeless or to wonder what it was that anything I’d done in my short time as an activist had really accomplished – and what doing it even longer would actually get done. Was I changing anyone’s life, or merely my own world- and self-view? Is it really possible to change lives, or the world, or anything? I’ve devoted my life to this movement, but I admittedly didn’t realize when I began that journey in college that holding my fellow Americans accountable for racism, sexism, classism, ableism, heterosexism, cissexism and other forms of discrimination would be this difficult. (I never, in my life, could have imagined the challenge of convincing people these issues were present problems for an overwhelming number of Americans as well.)

I know I wasn’t, am not, alone in feeling this way. High-profile cases that highlight America’s ongoing challenge to become more welcoming, inclusive, and – yes – loving of all of its people can often make activists truly aware of how uphill the battle will be. It can be hard to keep going when you can’t see the top. Sometimes I find that it’s become impossible to dream up an entirely new world; sometimes the idea of the movement succeeding seems almost like a dream and not a plan.

What made bell hooks’ quote on Tumblr more important than the rest was its age. Because aside from teaching us all an important concept of privilege in a simple, compelling way that related to the Trayvon Martin case, the quote also reinforced the idea that the racism and destructive hate we saw dominating in this case weren’t new or unique inventions in the courtroom. It reminded us of the history and legacy of racism this country still clings to, the impact it’s had on lives throughout generations and eras in our own development as a nation. And above all, it reminds us how lasting and important our work is, and must be, to stop that ugly history. The fight is not over, and neither is the dream. Activism is not instant and neither is social and cultural change; we have to be prepared to push forward even when we can’t see in front of us, even when our vision is blurred by tears and marred by anger.

This has all been done before and we have lost before, the quote whispers. And we kept going.

Keep going.

And if that’s not enough to make you a deep believer, or commit you to buying the bell hooks books in your Amazon recommendations, here’s nine more bell hooks quotes that haven’t stopped ringing true yet.

+ “The rage of the oppressed is never the same as the rage of the privileged. One group can change their lot only by changing the system; the other hopes to be rewarded within the system. Public focus on black rage, the attempt to trivialize and dismiss it, must be subverted by public discourse about the pathology of white supremacy, the madness it creates. We need to talk seriously about ending racism if we want to see an end to rage. White supremacy is frightening. It promotes mental illness and various dysfunctional behaviors on the part of whites and non-whites. It is real and present danger.” (killing rage: Ending Racism)

+ “A vision of cultural homogeneity that seeks to deflect attention away from or even excuse the oppressive, dehumanizing impact of white supremacy on the lives of black people by suggesting black people are racist too indicates that the culture remains ignorant of what racism really is and how it works. It shows that people are in denial. Why is it so difficult for many white folks to understand that racism is oppressive not because white folks have prejudicial feelings about blacks (they could have such feelings and leave us alone) but because it is a system that promotes domination and subjugation?” (killing rage: Ending Racism)

+ “It is necessary for us to remember, as we think critically about domination, that we all have the capacity to act in ways that oppress, dominate, wound (whether or not that power is institutionalized). It is necessary to remember that it is first the potential oppressor within that we must resist—the potential victim within that we must rescue—otherwise we cannot hope for an end to domination, for liberation.” (Feminism: A Transformational Politic)

+ “We have to constantly critique imperialist white supremacist patriarchal culture because it is normalized by mass media and rendered unproblematic.” (Homegrown: Engaged Cultural Criticism)

+ “Justice demands integrity. It’s to have a moral universe — not only know what is right or wrong but to put things in perspective, weigh things. Justice is different from violence and retribution; it requires complex accounting.”

+ “Dominator culture has tried to keep us all afraid, to make us choose safety instead of risk, sameness instead of diversity. Moving through that fear, finding out what connects us, revelling in our differences; this is the process that brings us closer, that gives us a world of shared values, of meaningful community.” (Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope)

+ “The process begins with the individual woman’s acceptance that American women, without exception, are socialized to be racist, classist and sexist, in varying degrees, and that labeling ourselves feminists does not change the fact that we must consciously work to rid ourselves of the legacy of negative socialization.” (Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism)

+ “All too often we think of community in terms of being with folks like ourselves: the same class, same race, same ethnicity, same social standing and the like..I think we need to be wary: we need to work against the danger of evoking something that we don’t challenge ourselves to actually practice.” (Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope)

+ “We are all suffering. When black males are in pain we are all in pain.” (We Real Cool: Black Men and Masculinity)

Comments

“The fight is not over, and neither is the dream.”

This whole thing is beautifully written, but that just made me tear up.

Thank you for finding light in the darkness, Carmen.

“It reminded us of the history and legacy of racism this country still clings to, the impact it’s had on lives throughout generations and eras in our own development as a nation.”

I liked this part. A lot of times people like to disregard the past as something that is irrelevant, but what they forget is that the past provides the context for the present and future.

We have to know our history (especially all the ugly and nasty parts) in order to bring about real change. Those who hold the knowledge of history are the ones who hold power. Want to disenfranchise a group of people? Easy. Deny them of their history – deny them knowledge of themselves.

That being said, I love bell hooks.

Excellent article, thank you. I really need to start reading more of her work.

“all oppression is connected you dicks” – staceyann chin

“After the Trayvon Martin ruling it was hard not to feel hopeless or to wonder what it was that anything I’d done in my short time as an activist had really accomplished – and what doing it even longer would actually get done. Was I changing anyone’s life, or merely my own world- and self-view? Is it really possible to change lives, or the world, or anything?”

It is difficult not to feel as if the world is hopeless at times like these, but bell hooks spoke to you, and me, and apparently a million other people on tumblr, and that’s activism. And if in our time we can awaken even just one other person’s senses to the forces of kyriarchy and encourage them to speak up along with us, then we will have done our jobs. Never give up hope. No matter how small your successes are, your activism is important and very much needed. Beautiful piece.

Oh my goodness this was such a lovely article. I’m actually a student at Berea College in Kentucky, where bell lives, and I’ve met her. She is just such a sweet human, and to hear her discuss what she’s seen in her life is absolutely incredible.

Her words are just sooo good. Thank you for this piece!

really beautifully written, carmen. thank you.

THANK YOU OMG. <3

Bell hooks!

This is as good a place as any to recommend that folks check out the podcasts at artistactivistniaking.com. they’re hr-ish long interviews with (mostly) queer and trans poc artists, and there is suuuuch wisdom in them. Huge gift to the world.

I was actually rereading Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center last weekend sort of on a whim and bell’s writing is always so devastatingly current, even though it’s actually 25 and 30 years old. It absolutely breaks my heart that things I read from her works from the 70s still ring so true today. I read the book first for a senior seminar in the history of feminist thought and now I’m basically obsessed with all of her work. Intersectionality seems so obvious, I don’t know how it didn’t happen before her within the larger feminist framework.

Commenting on Trayvon Martin, I feel like this case has really highlighted a large-scale ignorance of race politics and race relations in this country. That people can sit on Twitter and say “George Zimmerman isn’t white,” and think that makes what he did not racist, demonstrates a fundamental lack of understanding of what racism is. Also, that Trayvon Martin, and really all black males, can be characterized and demonized in the media as violent thugs is a crime in and of itself. It’s generalizations like that which propagate institutionalized racism.

I think I’ll be done for now. I already went on a long soapbox rant to one of my professors earlier this week. *sigh*

Thank you for this, Carmen.

Somehow in the various classes I took in college I managed not to read much bell hooks, which is awful, I know. I’m wondering — does anyone have any recommendations as to where to start? She’s written so much and I can’t decide if I should start at the beginning and work my way forward, or start in the middle. Any thoughts?

When it comes to bell hooks, you can start anywhere and it will be the beginning.

I will say if you want to dip your toes before diving in, start with all about love.

Absolutely outstanding post

Red flowers, yellow flowers, flowers, flowers, flowers, flowers, flowers, flowers, flowers, flowers, flowers, flowers bloom, but the best thing we do is swear at the person behind me We’re good at pooing. We’re not good at pooing anymore. It’s because of you. You’re so tactless and you can’t work토토커뮤니티

Thank you so much for your kindness in delivering good news 먹튀검증 and I felt responsible for receiving this warm energy and sharing it with many people

Nice to meet you. I happened to see your post, and Neagle is addictive, so I will come to see your post again. I hope you post a good one again. See you again먹튀검증

I miss you. I miss you so much that I don’t want to forget because I miss you so much that I can’t forget so many things that I couldn’t forget. This song is a song called “I miss you, miss you, miss you.” It’s so good that you should listen to it토토사이트 and I felt responsible for receiving this warm energy and sharing it with many people

Hi, happy day. I’m here to see Neagle I was very impressed to see it I think I’ll be visiting your page again I’ll be backhttps://mtygy.com

After reading these posts while I was really busy, I felt like it was a big break because I was lost in contemplation메이저사이트

Hi, happy day. I’m here to see Neagle I was very impressed to see it I think I’ll be visiting your page again I’ll be backhttps://mtygy.com

After reading this article, I think it’s a good article that has a lot of meaning먹튀검증 and it’s a great word that really makes your head and chest realize a lot of things

A Granite holds a rich beauty beneath it that only a few other materials can match. The timeless aura & appeal of a granite slab can only be seen in natural products. https://totovera.com/

I appreciate your valuable post. The article is very concise and neatly organized, so it fits more easily in the head. I hope to see your good posts again in the future. https://totogorae.com/

What inspired you to write such a good article? It’s amazing 먹튀검증I can’t help but clap. It’s a revolution.

Wow, how can you write this? You’re so smart. Aren’t you a genius? It’s awesome. It’s so much fun that I’ll come back to watch it’ I’m just looking forward to your posting again레플리카사이트 and I felt responsible for receiving this warm energy and sharing it with many people

What inspired you to write such a good article? It’s amazing 먹튀검증I can’t help but clap. It’s a revolution.

I miss you. I miss you so much that I don’t want to forget because I miss you so much that I can’t forget so many things that I couldn’t forget. This song is a song called “I miss you, miss you, miss you.” It’s so good that you should listen to it레플리카신발 and I felt responsible for receiving this warm energy and sharing it with many people

I showed this to a lot of people The writing is so good that it’s a waste for me to see it, but everyone says the same thing. The writing is so beautiful. As expected, I was proud for no reason because I wasn’t the only one who thought so메이저사이트

I want someone to make a book out of these short and beautiful texts, and I’ll probably be the first to buy it레플리카시계

I really want to say thank you to you for giving me a lot of positive influences 토토사이트 I think it’s the best article I’ve ever written this year

Wow, how can you write this? You’re so smart. Aren’t you a genius? It’s awesome. It’s so much fun that I’ll come back to watch it’ I’m just looking forward to your posting again레플리카사이트 and I felt responsible for receiving this warm energy and sharing it with many people

I showed this to a lot of people The writing is so good that it’s a waste for me to see it, but everyone says the same thing. The writing is so beautiful. As expected, I was proud for no reason because I wasn’t the only one who thought so메이저사이트

Wow, how can you write this? You’re so smart. Aren’t you a genius? It’s awesome. It’s so much fun that I’ll come back to watch it’ I’m just looking forward to your posting again레플리카사이트 and I felt responsible for receiving this warm energy and sharing it with many people

I showed this to a lot of people The writing is so good that it’s a waste for me to see it, but everyone says the same thing. The writing is so beautiful. As expected, I was proud for no reason because I wasn’t the only one who thought so토토사이트

I really want to say thank you to you for giving me a lot of positive influences 토토사이트 I think it’s the best article I’ve ever written this year

Wow, how can you write this? You’re so smart. Aren’t you a genius? It’s awesome. It’s so much fun that I’ll come back to watch it’ I’m just looking forward to your posting again레플리카사이트 and I felt responsible for receiving this warm energy and sharing it with many people

I think this is so funny! I’m looking forward to the next upload주소

I want someone to make a book out of these short and beautiful texts, and I’ll probably be the first to buy it레플리카시계

I showed this to a lot of people The writing is so good that it’s a waste for me to see it, but everyone says the same thing. The writing is so beautiful. As expected, I was proud for no reason because I wasn’t the only one who thought so메이저사이트

It’s so refreshing to see a celebration of butch women and tomboys from the early 20th century. These women were trailblazers and role models, and they deserve to be remembered and celebrated. I especially appreciate the inclusion of women of color and women who were not exclusively attracted to women. It’s important to remember that butch identity is not monolithic, and there is no one way to be butch.