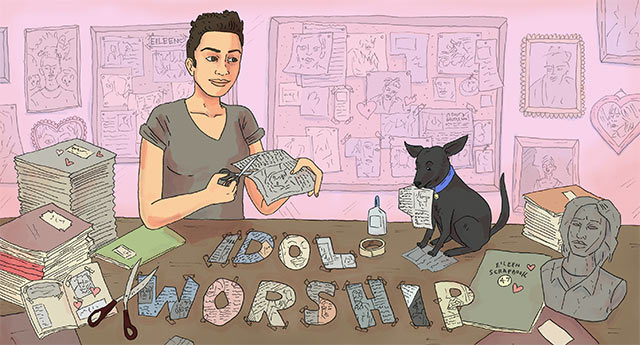

Welcome to Idol Worship, a biweekly devotional to whoever the fuck I’m into. This is a no-holds-barred lovefest for my favorite celebrities, rebels and biker chicks; women qualify for this column simply by changing my life and/or moving me deeply. This week, I’m spilling my guts about one of my original gut-spilling inspirations: Alanis Morissette.

Header by Rory Midhani

When I hear Alanis Morissette I think about my mom. I don’t think she would get that if I told her, and I never really have, but my friend Amanda and I always had this recurring joke with each other about growing up with newly-divorced moms pre-divorce-era, and what it was like riding in the car. There were two options: “Torn“, by Natalie Imbruglia, and “You Oughta Know,” by Alanis. Chances are, when you were about six, either one was on the radio. And your newly-divorced-mom pre-divorce-era knew all the words.

Growing up, I felt like not a lot of people “got” my family. My mom struggled to make ends meet; we changed schools frequently just because we needed to find new places to crash when the landlord finally gave up on us. Nobody’s parents in suburban New Jersey were divorced (yet) and when people asked Carmen Rios in 1995 “where her dad was,” she burst into tears on the spot. (Spoiler Alert: I never really knew, nor could I fathom why everyone else always did.) Popular culture certainly didn’t know: in a sea of shows about happy and slightly less happy families, still absent was mine. We were doing okay, like the little troopers we were, like the Three Musketeers we had deemed ourselves (a name my mother, to this day, uses to refer to my brother, myself, and her – collectively), but our stories were missing. And there was something in the grungy, frustrated, self-indulgent melancholy of nineties women that struck me, always, as being the most relatable and normal thing out in the world for me to consume. While other girls were listening to Britney Spears, I was still stuck on the reflective stuff, still singing Alanis Morissette to myself in my mother’s car.

And it didn’t end there.

I went to college in 2008, and there I met Josh. “You Oughta Know” was my song before I’d ever drank a beer and found MY SOOOOOONG!, and that’s saying something. We used to play it just to listen to it, just to remember it, just to feel more like anyone had ever walked in our shoes before that day. Growing up, I couldn’t grasp what a “self-fulfilling prophecy” was, but I did understand my own romanticization of what had brought that song into my life. I was convinced, when I dated men, that ultimately those relationships would be broken. I was convinced, for a short time into dating women, that those were destined to be that way, too. If my mother’s song was “You Oughta Know,” mine was “Hands Clean,” the tidied-up version of Alanis’ angst that broke later that decade. I internalized and conceptualized of a relationship where my feelings lingered past the ending line, where I was stuck singing stupid songs in stupid cars, where all I was for a while was someone hung up on one moment where everything changed. I was right about the self-fulfilling prophecy, and I was right about the song – it fit just as good in my headphones as the others had in my mother’s car.

Being 23 though, everyone else knows and loves these songs, too. If I could count on my fingers every time I’d listened to “Hand in My Pocket” and thought “holy fucking shit this is my LIFE STORY right now,” when I was unemployed, I would have had enough hands to cut off and sell on some weird black market to eat dinner for years. Even if I came of age in the 00’s (which, by the way, how fucking lame is that) there is a part of me that sits squarely in the decade before, the part of me who grew up hearing these sounds and seeing these images and will never be a different person because of them. Once you’ve seen clashing plaids in one outfit, you’re done for life. You’re never going to be whole again.

It was like that even moreso with the music, which I still cling to and now I listen to because it’s winter and I just want summer, and the nineties felt like an endless summer where the boys had hair like Pauly Shore and the girls wore bikinis on the beach and everyone lived in California. I didn’t get, as a kid, that the angst was about inequality, or inherent gender poison, or the way it feels to be rendered an object and an invisible force to the very sex people want you to be attracted to. I didn’t get that Alanis was a revolutionary in her own right, or that she was singing about the complacency of an America in prosperity or the recovery of an entire generation from the prudes who reigned before them. I didn’t even know she was actually smoking a cigarette with that other hand, because I was too busy watching Dogma into my later years to think about anything but how fucking long her hair was. I watch her videos now and I see all of these classic signs of a volatile politic inside of a polite body and I cringe to think I ever thought all girls were like that, but then I pat myself on the back for being that idealistic.

What if we were all raised by Alanis Morissette? She has this philosophy that, to this day, describes me to the bone: make mistakes, feel something, be honest about it, and recover. Get naked about your feelings, and with your body, if you want, and know that you’re going to be okay on the other end. There was always the idea, inside of her words, that eventually she was going to recover, and she was going to be fine, she was going to brush her hair and maybe put some wispy eyeshadow on and be okay. And you were, too. My mother always knew she was going to make it, and she told me women could and would do anything, and the nineties felt like that to me, maybe because I was a kid, or maybe because nobody had the Internet and thus most of our formative experiences actually weren’t public showcases later integrated into our “personal brands”. The nineties felt like being forgiven and starting over no matter how many fucking times you’d been back to the starting line. You live, you learn. Thank you, India. Isn’t that so fucking ironic? (It’s not, but be honest, you didn’t know what it meant, either.)

I think what brings me back to nineties music, again, and again, and again, and again, is always that vibe: nothing really matters. You’re all you have and this is all you’re working with and you know what, slugger? You gave it your best fucking shot, and that’s what counts. We’re all infinite. We all have a second chance. There are no economic problems weighing on our institutions, no wasted moments going to war, no worries outside of whether or not you’re using Pantene Pro-V or something. Alanis Morissette made so many mistakes, and she accepted her own futility at trying to stop herself from becoming one as well, and she threw in the fucking candle. In 2005, Alanis released “Everything” and cut all her hair off, y’know, to keep up with the times, and I remember vaguely staring at the screen thinking I know her from somewhere and not placing it at first. But the words rang back to my mother’s car, to everything she’d probably wanted that whole time, that any of us wanted, that I still want.

I blame everyone else, not my own partaking

My passive-aggressiveness can be devastating

I’m terrified and mistrusting

And you’ve never met anyone as,

As closed down as I am sometimes.You see everything, you see every part

You see all my light and you love my dark

You dig everything of which I’m ashamed

There’s not anything to which you can’t relate

And you’re still hereWhat I resist, persists, and speaks louder than I know

What I resist, you love, no matter how low or high I go

Having been in feminism for over twenty years now (it starts at birth, you know), I’ve spent so many days trying to “put my finger on it” (ugh, that’s what she said) that it almost is laughable that I never put it right here. Or, right there I guess. On those ten years I spent being born, being new, being unaware, being dumb, being innocent, knowing I had second chances, knowing my mother’s life was a second chance, knowing I was her second chance. The nineties always feel formative to me, but my life wasn’t a Sugar Ray song or a Jewel song or any of that – it was, it is, an Alanis Morissette song. It’s mistakes and learning how to forgive myself, which, at some point, became a lot harder for me and the people in my life than it used to be for the people who raised us. Being imperfect was all the rage in the nineties, and people were open and honest about their imperfections and their flaws and the things we didn’t realize yet we had the capacity to “fix,” or maybe had never contemplated having to fix at all. The nineties were gritty and human and fleshy and raw, and nobody got famous from autotune and everything was heavy and sincere and even girls were allowed to tell the truth about how they were feeling. I spend all of this time putting my hands up in the sky and trying to get free but really, I’ve been free inside the whole time, mostly because I was raised by revolutionaries.

Revolutionaries, and a really good FM radio.

Comments

Carmen I love you for this!

The first thing I think of with Alanis is 90’s car trips too!

There was this girl I had been friends with as a kid in school. She got a copy of Jagged Little Pill for her eighth birthday and when her mom took the two of us to the next town over for McDonalds and a trip to the cinema – two luxuries our little town didn’t offer, we insisted on playing the album beginning to end, over and over, the whole way there and the whole way back, singing along at the top of our voices, except for the curse words of course, reading the cassette tape liner note lyrics and debating furiously over what the more confusing bits meant.

Postscript: Guess which two girls out of our all girl convent school class of 20 turned out to be queer?

I woke up with the song “Front Row” stuck in my head . . . and now I’ve just read this, and I’m crying because Alanis is just this incredible artist that has continually been relevant and sacred and important to my life/lives. Throughout the years, in one way or another, her music has been part of so many of my life experiences/growing pains.

Thank you for sharing this.

omg this makes me so happy, alanissssssssssss!

this is perfect.

My mom is not divorced, and in the 90’s I don’t think she was unhappy, but yet Jagged Little Pill was on constant rotation in the car throughout my childhood. That album will always remind me of family ski trips. My sister and I would race each other down the hill, belting out the lyrics to All I Really Want or Right Through You as the old folks gingerly making their way down would give us weird looks and we’d just laugh our heads off and keep screaming “Took a long hard look at my ASS and then played golf for a little while!”

And then later, Perfect would become the song that spoke to me more than any other, and to this day if I think about it too hard it can still make me cry.

I very closely relate listening to Jagged Little Pill with finding out what a feminist is and that I could be one from my recently divorced, chain smoking mother. This artice made me cry.

Alanis Morissette is God. Dogma taught us that! (As well as making me miss George Carlin). I actually bought one of Alanis’ CDs recently (who does that any more?) and flicked through the lyric book… I just love how she writes.

Also, every time I listen to Ironic and the lyric “…meeting the man of my dreams, then meeting his beautiful wife…” plays, I ALWAYS think “She’s gotta be bi!”… in my dreams maybe?

jagged little pill came out when i was an angsty middle school kid with absolutely no idea what she was talking about in any of those songs but oh god they spoke to my SOUL.

Oh my goodness. My girlfriend and I recently had this conversation, and when the album “Jagged Little Pill” came out, she asked for it as a gift, and received the entire thing on cassette but an instrumental version? Played by a symphony or something. She never got the real version, listened to it anyway, and only knows it as that. I found it kind of hilarious.

The first thing I think of when I think of Alanis Morissette is also my mom! She used to have a playlist of angry songs she’d play really loudly whenever her boyfriend pissed her off, and it featured Alanis Morissette pretty heavily. He’d come home and say “I know you’re angry at me!” and she’d deny it and Alanis Morissette would demand “Is she perverted like me? Would she go down in a theater??” and he’d say something about not being an idiot. Good times.

“Jagged Little Pill” is one of my favourite CDs of all time.If I hear this or, “Before he Cheats” come on the radio I pump up the volume and angrily sing along. I am not straight, but caterwauling ( I sing, OK )with Alanis is my way of singing for my sisters who have been thrown under the bus by some slimy guy. I feel as if most women, straight or gay, learn the lyrics to “You Ought to Know” instinctively.

I want to know what to say…but all that I can think is that I really, really, really fucking loved everything about this.

Hand in My Pocket is a perfect song. I can’t even say anything else about it.

Dude whoa. You and I are the same person I’m pretty sure. My mom was newly divorced in the 90s while I was growing up and Alanis was totally totallyyy what we listened to. About two years ago I was listening to 90s radio on Pandora and heard all of these songs I remembered from childhood that my mom played in the car ;) They were all Alanis. I’ve been madly obsessed with her ever since. TOTALLY related to this story! Thank you!

there has been a systemic shortage of the role of Jesus being played by cute women actresses in clubbing gear. Anyone who has tried to alleviate that problem is my object of admiration and has a special place in my heart, forever.

When I was younger (10 or 11) we had a karaoke machine that was definitely not made for children. It had a bunch of like adult alternative songs on it, including a ton of Alanis Morissette. I would go into my bedroom and sing Alanis on the karaoke machine by myself and have all the feelings (even though I was definitely too young to understand anything I was singing).

Also, I recently heard on the radio that Lorde beat out Alanis as the female artist with the longest running #1 song on the alternative chart thanks to “Royals.”

O Lilith Fair, where art thou? The patchouli scented days of yore…

Love this post! Music has been super super important to me.I have this lineup of women-musicians that I play all the time: Joan Jett,Alanis Morissette, Hunter Valentine, Brody Dalle, Cyndi Lauper, Jewel,Melissa Etheridge…

“Hands Clean” was one of the first songs I ever listened to that made me realize I was madly in love with my best friend. That junior and senior year of high school was one of the hardest of my life.

And that one lyric:

We flash forward to a few years later

No one knows except the both of us

and I haven honored your request for silence

And I still recall that feeling.

Brilliant. I know whenever I need to forgive myself, or get a good look at my life, or just lighten my mood; there is an Alanis Morissette song for that.

My mother listened to Alanis when I was growing up, too. For us, she also brought so much from her religious/spiritual journey to her music. As we came from a Catholic family, we attended a church a couple times a year, but my mother grew up in the church. I think Alanis’ spiritual branching out was a great example for other Catholics. Other than midnight mass and Easter mass, my mother never pushed anything on us. We even had books and videos about many different religions and given all the options. I’d like to think it was due to a cultural shift of the time and that Alanis could be seen as a contributor. I too adapted her philosophy as my own through listening to her music, in a time of my life that had to live and learn the most (high school). I am appy to say I am one of those 20-somethings, who was raised on/by Alanis Morissette.

OMG, Jagged Little Pill was probably the most important album to me, standing out from all the other 90s music I loved as an anxtful, anxious pre-teen! I remember being 12 years old, eating pop corn and drinking yoohoo while my mom let me blast Alanis Morissette on our stereo while my unstable, unpredictable firefighter father was away on his 24-hour shifts. I, too, had no clue most of the time what most of the lyrics referred to, and I, too, studied the liner notes for hints, but was still hopelessly clueless. I still admire her a great deal today!