“I feel so weak physically right now. My body has that feeling you get from throwing up for days or something. Even putting my fingers around this pen hurts. My wrists, elbows, back, legs, everything. What’s wrong with me? What’s happening to me?”

– Diary. December 24th, 2000

At some point between returning to Michigan from New York that summer and the Christmas morning in Ohio when I woke up immobile, my body had turned on me. See, I don’t know where the story of how I got sick or when I got sick or even why I got sick starts. I think it started that summer, the summer of 2000. But maybe it started earlier, like the summer before, when I’d just graduated from boarding school — the only place I’d been happy since my father died — and decided to eat a lot less and run a lot more.

Like if I stopped eating, I could stop growing up. Like if I kept running, I’d get somewhere.

I hated my body and punished it, and it hated me and punished me back. Is that what happened? That’s the thing about getting sick the way I got sick: nailing it down. Sometimes it seems like the story started when I was 14, or maybe even earlier. It gets mixed up with other vague diagnoses, and other parts of myself I learned to name months or years after I started to feel them, like being gay, like depression, like ADD, like being a “writer.” I know that I am these things, but I don’t know why, and I don’t know if I tell stories like this one to convince you that they’re true, or if I’m the one who needs convincing.

Doctors are not, it turns out, vending machines. You can’t just insert a collection of symptoms and expect them to dispense an accurate diagnosis and its accordant remedy. Doctors are also just people and they don’t know everything because not everything is known, and maybe not everything is meant to be known.

But we want to know. We want to name our pain and desire and we want language that describes what happens to our bodies, and we want that so badly that we’ve come to need it, too.

In the spring of 1999, during my last months of boarding school, I started working out. This was a big deal for me. I’d always been naturally thin and hopelessly clumsy, so I was never a great athlete and nobody told me I needed to exercise, until I stopped getting taller and started taking the pill and the world and I suddenly perceived my body to be a final product in need of care. I’d never been very good at being a girl, but I read magazines and paid attention to what the other girls talked about and I knew that maintaining the size of one’s body was a crucial aspect of womanhood.

Exercising started a conversation with my body I’d never had before. This dialogue was so certain and understandable in a way nothing else about life had ever been, back when my body was just a vessel that carried my soul and brain around. Soul and brain stuff was murky and unpredictable: writing, relationships, love, friendship, all of that. But the body was science, was weights and measures, was physical facts, and I liked that.

What I hadn’t learned yet, but would soon enough, is that even the body is not meant to be known.

I started at Sarah Lawrence in the fall of 1999, an irritable bag of bones, and right away my depression hit me hard in a way it hadn’t since early adolescence. I had a hard time making friends. I couldn’t sleep. I was constantly on the verge of tears. I ate Slim-Fast bars and cucumbers all day and at night I ate cookies and entire cakes and sometimes threw them up. I spent every weekend in the city with my friends from high school, going to museums and off-off Broadway plays, eating long lazy brunches and drinking at sketchy East Village dives that sold ecstasy and served teenagers.

Then I dropped out of college and moved to Manhattan and decided I could overcome my depression and everything by telling everybody I was happy, listening to a lot of Belle & Sebastian, writing in my diary on the subway and eating “whatever I wanted.”

But I’d lost sight of “what I wanted” already — what did I want?

I wanted somebody to tell me how to be a person.

Nobody did.

So I waited tables, did internships, drank a lot, gained 15 pounds and completed an “Independent Study’” for Sarah Lawrence which involved writing a screenplay about the evils of anti-depressants inspired by the Magnetic Fields’ “69 Love Songs.” I slept with a 27-year-old law student who didn’t read books. I didn’t feel any closer to figuring out how to be a person than I had at Sarah Lawrence, so I transferred to the University of Michigan, in my hometown of Ann Arbor, because it seemed like a less expensive place to lose my mind.

After arriving home, I had about a month before I’d move into the dorms, which wasn’t enough time to get a summer job but was enough time to persistently overanalyze my feelings (like my relationship with aforementioned 27-year-old law student) and obsess over things (like my abs). I was always tired but could never sleep. I drank half a bottle of bubblegum cough syrup every night to get to sleep, and popped workout pills and guzzled Diet Coke to stay awake the next day.

I felt like everything was out of my control except this one thing — physical fitness — and if I could excel at that, I’d be okay, so I took a lot of spinning and yoga classes and read a lot of fitness magazines.

I was being flexible, literally and figuratively. When other sources of stability, like the close friends I’d made in boarding school who now lived in New York, weren’t around anymore, I found something new to keep me stable: exercising.

But my body had other plans, because this is when the pain started like a prank the world was playing on me. It started in my knees, and it felt like my knees were trying to become lighter, and pressing out on everything around them, like somebody had replaced my knee with a giant cold metal bolt and the bolt was malfunctioning. Touching the joint was like touching a bruise. I assumed it had to be an injury from some kind of athletic activity, even though nothing about it felt like those kinds of injuries. It felt more like something invisible was swollen.

In the ensuing months I’d often wish I’d never started exercising. I’d fantasize about three-years-ago me who wouldn’t have given a shit about losing mobility. I needed something else to control, now — I picked schoolwork, of course, but also tightly controlling everything I ate, and writing it down.

Over a decade later, I’d see Battlestar Galactica for the first time, and seeing those pulsing red spots of light tracing Sharon’s spine was the first time I saw something that looked how I’d felt that year. What’s more is that it must have always been that way, right? Her spine must have always been like that, even before she knew she was a Cylon. This thing can be inside you for so long before it shows itself.

I started at Michigan in September 2000 and from the get-go it was clear I’d never really fit in there. I hopped from friend to friend, trying to find somebody who made sense: Sabrina the beautiful smart manic pixie dream girl from the Residential College who eventually faded ’cause she didn’t live on my side of campus, Katie the bitchy ex-cheerleader, Marsha the wide-eyed Jewish virgin from Maryland, Stacey the anorexic from Phoenix who was always doing Tae-Bo in the common room.

I had a single, so I didn’t have to deal with roommates, but the noise in the hallways kept me up all night and construction noise rattled me awake early every morning. I’d always battled insomnia and constant fatigue, and the less I slept, the more my knees would hurt, the more I’d feel like my entire body was swollen.

Although I’d waited my whole life to escape Ann Arbor and my Mom, this situation made her proximity a welcome relief. I was 19 years old but hadn’t needed my mother so desperately since the months after my father died.

I started sleeping at her house sometimes and taking the city bus to class, further distancing myself from any kind of social life I could have at school. My Mom, like me and everyone I talked to about the pain, figured it had to be the result of some mistake I’d made at the gym, but that hypothesis was increasingly impossible to prove.

I was just that smart artsy girl who’d gone to boarding school and lived in New York City by herself, some exotic animal amongst flocks of neat suburban exports on their own for the first time. After Sarah Lawrence and boarding school, I’d gotten used to having friends who’d endured psychological trauma and therapeutic treatment, who had dysfunctional or non-existent relationships with their parents and hometown, who’d made self-destructive decisions for all the wrong reasons and then made art out of it later. I’d never been surrounded by so many normal children from normal families in my life and I didn’t know what to talk to them about.

I was lonely like a knife cleaving my chest, lonely like an empty hole in my gut, loneliest while walking home alone from the library, past groups of grinning, raunchy boys in fitted caps and t-shirts, girls with straightened hair and made-up faces in tiny shorts and skirts, past their shimmering slender legs, past their easy laughter and their exaggerated gestures of friendship towards each other. What did they have going for them that I did not. Why was this so easy for them.

One night Katie and I lurked outside the dorm room of two guys we’d spent the night hanging out with to see if they would talk about us — and they did. She’s really hot, they said of Katie. But such a bitch, though. They laughed. What about Marie, though? One guy asked. She’s super smart, one guy said. Really smart, yeah, and funny, said the other. Not like I’d wanna see her naked or anything, said the first guy, and then everybody laughed.

“I can’t believe they fucking said that about me,” Katie said, quickly, in the safety of the stairwell.

I wanted to punch her in the mouth because she could stop being bitchy if she wanted to but I’d always be ugly. Instead I went back to my room, wrote down my numbers for the day, ate three pieces of carrot cake, cleaned the knife, and then took it to my skin. It was the first time and not the last. It seemed like the thing to do and so that’s what I did instead, and it didn’t hurt like my knees hurt.

The pain was scary, sure, but what was more scary was not knowing where the pain came from, or what it might mean or turn into. The face of things to come.

Eventually I’d become best friends with a photography student named Emily shortly after she moved in to the single next door, an event which required flying her Mom in from Westchester to help move buckets of overpriced yoga pants from one end of the hallway to the other. Emily had money, a huge network of other cute well-dressed rich Jewish friends from the East Coast, and didn’t eat carbs. But she was funny and creative and smart and perceptive and loved Ani DiFranco and could make fun of the scene her friends were so earnestly invested in, and we actually clicked right away. Emily was beautiful and hot but she wasn’t skinny, and in her social circle, that was basically the worst thing a human being could be: not skinny. So that gave her some critical distance.

We talked about starting a Teen version of Vogue when we graduated, and I’d be the editor of words and she’d be the editor of pictures and fashion. (Eventually, Vogue beat us to it.) We were an odd couple but it worked, and I loved her and she loved me, and I hated me, and I hated me even more when we were around all her pretty friends with Jewish boyfriends who survived on diets of lettuce and mustard. But these girls were popular, and now that I was friends with Emily, they became friendly to me, and that was nice.

The only thing I had in common with most of my new friends, though, and the thing I’d never had in common with my former classmates, was an encyclopedic knowledge of calories and an intimate relationship with the gym. They wanted to go running and take cardio hip-hop at the CCRB. I’d tag along, feeling like a real normal girl with her girlfriends going to the gym. This I could do. I could do this.

Until I couldn’t.

I went to my classes, read my books, aced everything, impressed all my teachers. I’d always been good at what I was good at, I had that under control. When school or life got stressful I did what I’d done all my life to manage stress: I took a long walk or went on a bike ride. Ann Arbor was a great place for long walks ’cause I’d grown up there and, like all college town residents, knew where to go to avoid other students. The fact that I was also a student now didn’t change my desire to avoid them. If anything, it was amped up.

But my mind-clearing walks were becoming obsessive, mind-consuming meditations on pain. I couldn’t think about anything while walking besides how much my knees and lower back hurt.

Also, I kept getting larger, even though I hadn’t changed my eating habits. It was strange. At the time I thought maybe I was growing into my adult body, but later after my diagnosis and recovery, I’d go back to the wiry human I always was, and nothing like that would ever happen again. But back then I felt like I was pregnant with myself. I looked fine, of course — healthier than normal, probably. But I felt off. It just didn’t feel like my body anymore.

My Mom had hypothyroidism and described how she felt when it first kicked in: like I was gaining weight while sitting still. Coupled with my fatigue and anxiety, this inexplicable weight gain suggested that maybe I, too, had a thyroid disorder.

They tested my blood. It came back negative. I didn’t realize ’til we got the results back how much I’d been hoping for that to be the problem, just so that I would know what the problem was.

In the winter I started physical therapy at MedSport, a facility out by the highway overlooking an ice skating rink. I didn’t have health insurance, but my Dad had left money behind and nobody bothered to tell me how quickly all this “treatment” would burn through it — the price inflation on medical services wasn’t a thing I knew about yet.

My physical therapist didn’t know what was wrong with me, either, so he just walked me through a series of exercises no different than what I’d done when I had a personal trainer in New York and no chronic joint pain. I was jealous of the other patients who got hooked up to Iontophoresis machines with blue gel and little electrodes after their physical therapy sessions. Those machines seemed mysterious and therefore effective.

Mostly I wanted medical advice, for somebody to tell me where the pain was coming from and how to stop it from getting worse.

“If I run, will that make it worse?”

“Mmm, maybe stay away from that.”

“Why?”

He shrugged.

“But I can use the elliptical trainer, right? I mean it’s like, no impact, so it couldn’t really make this worse?”

“It could.”

He advised I stick to swimming and take three ibuprofen every three hours. So I did, even though I hated swimming and the ibuprofen rarely made a difference. My skin smelled like chlorine and now it was winter and my hair froze on my walk home.

The pain had been located exclusively in my knees for most of the fall, but by winter it had crept into my elbows, too, that same tenderness, those Cylon pulses of light.

“So, now my elbows have started hurting too.”

“Maybe you have arthritis?”

“But I’m 19 years old! How could I have arthritis?”

He shrugged. It was his signature move.

At some point I gave up tagging along to frat parties with my sorority friends. Why couldn’t we just skip ahead to the part of the night where we go to Panchero’s and get quesadillas, I wanted to know. I started hanging out with this guy Logan, a big heartthrob at Michigan who Katie and ten other girls had crushes on. Emily and I were the only ones uninterested in boyfriending him, which’s maybe why he liked hanging out with us. We’d talk and joke in my room for hours, listening to Barenaked Ladies and Aerosmith. He’d complain about hook-ups who wouldn’t “put out” and so one night, I did. Sex wasn’t a big deal for me, honestly, and I didn’t think much of the fact that I’d be the only girl he’d had sex with besides his high school girlfriend. It seemed fun, I guess.

The actual intercourse lasted approximately thirty seconds. We hooked up again the next night and then he stopped talking to me. Stopped saying hi to me, even. I wrote him a long letter and marched down to his dorm room to deliver it, intro’ing our talk with, “So are you just gonna ignore me forever?” I wanted to assure him I wasn’t interested in him as a romantic partner, just as a hook-up buddy, although honestly my main interest was that people might think I was cooler if they’d heard we’d hooked up. (That part of the plan worked swimmingly, for what it’s worth.)

He avoided eye contact, and then managed, “it was meaningless and that’s not right, you know?”

“But I thought that’s what you wanted?”

It seemed like nothing I knew how to do with my body was the right thing to do anymore, even if it was something I’d been asked to do, even if it was the only thing I’d been told everybody wanted women to do in the first place.

It’s alienating to live with an undiagnosed illness. You’ve got no clue how you’ll feel the next day, or what to do about it if you do. The future is fuzzy, the present is unclear. You’re waiting to find out what’s wrong, but don’t know who’s gonna end up telling you, or when. Emily wanted to make plans for living in New York City the next summer, but I stared at internship listings in the Career Center and wondered if I could do any of them lying down.

I’ve had major bouts of depression throughout my life for various reasons, but that first year at Michigan was the saddest and loneliest I’d ever been for no reason at all. At 19, everything seems potentially permanent and therefore terrifying — you’re between childhood and adulthood and clues shoot from all directions about what that adulthood might look like. Mine was foggy as day: I’d get straight As, be single forever, and my body would never work again.

After finals, I stopped exercising altogether. Surely exercise was the reason I’d gotten hurt in the first place, so I’d just stop exercising and wait on my ass for shit to get better.

Shit did not get better.

I took my three ibuprofen every three hours.

I sat very still.

Shit did not get better.

Shit got way fucking worse.

On Christmas Day I hobbled out into the living room when I heard my grandmother up making coffee. She and my grandfather lived in a tiny house on State Route 72 in Southwest Ohio, just outside of Wilmington. My Dad grew up there, in a big white farmhouse they’d sold when I was a kid for a more manageable place. Grandpa had quit farming and became a truck driver, but when my Dad died, Grandpa retired. Everything changed after that for them. For example, my grandmother was eventually diagnosed with fibromyalgia. She’d been in constant pain pretty much ever since. “I’m just like the Tin Man, honey,” she’d joke. “Your old grandma’s just creaking around.”

I could smell the coffee. “Well honey, you’re sure up early,” she declared, hand on hip.

I must have looked so young and old then, all at once, so scared and also so slow. “I… think… I might be sick?” I told her where I hurt and she asked, “Well sweetie, maybe you have what I’ve got?”

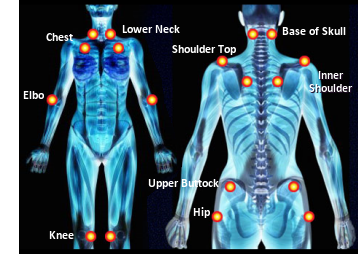

When you’re 19 and your 69-year-old grandmother suggests you’ve got what she’s got, you know you’re in trouble. But she had books and papers and a whole binder of information and she pulled them out for me and I read them and looked at the pictures, especially the picture of a human body with little red dots where the pain was.

She explained that fibromyalgia was caused by physical or mental trauma, like a car accident or somebody dying. For some reason that was the hardest part to swallow — could this have come from the same place for both of us? Because when it happened, I stayed strong, you know? I handled it. I didn’t take medication or start therapy or talk about my feelings. My Dad’s death had destroyed everything around me except me. What if it had just been saving me for last?

This day, Christmas, is especially foggy in retrospect. I know it was decided, somehow, with my grandmother and my Mom and everybody, that my brother and I should go back to Michigan that day and not stay out the week, because I needed to see a doctor. Did I drive home? If so, how? I don’t remember getting home, or sleeping, if I slept, or waking, if I woke.

According to my diary, I had a blood test for arthritis on December 27th, and then saw a rheumatologist on January 6th. I knew the rheumatologist, I used to babysit for her daughters back when we lived across the street from them, before my parents got divorced. I remember being so shocked by the number on the screen when they weighed me that I audibly gasped. The rheumatologist touched all these spots on my body and asked me how they felt. I was tender in so many places, it turned out, but hadn’t known it, because it had been so long since I’d been touched.

I felt like suggesting fibro would be leading the witness, so I didn’t, but she reached the conclusion on her own.

She prescribed a small dosage of Elavil, an anti-anxiety medication, to take before bed, and Celebrex, a painkiller usually given to seniors with arthritis. I had my words. I had a name for how I hurt, and I had the appropriate pills.

I never know how to describe Fibromyalgia, so I usually use a lot of non-specific words in a row, like “pain joint fatigue disorder syndromey thing.” But that’s only one of many problems I have communicating with others about the situation. The word itself, for example, is one or two letter swaps away from sounding like something involving vaginal discomfort and I’ve only recently cemented my ability to spell it properly. The word has an actual origin, however: fibro- is derived from the new Latin meaning “fibrous tissues” and myo- and algos- are Greek for “muscle” and “pain,” respectively. But there’s also something about it that sounds imaginary, like medical researchers scooped every errant symptom from their proverbial junk drawer and tossed it into a syndrome processor and out came this stew of sickness they named “fibromyalgia.” My mother, who took more interest in learning about fibro than I ever did, came home from a presentation on the topic convinced that just about every weird thing that had ever been wrong with me, from eczema to generalized anxiety disorder to hyperhidrosis, could be explained by fibromyalgia.

Indeed, many humans don’t think fibro is “real.” They think it’s another crackpot invention from Big Medicine and Big Pharma, and usually these people know somebody — an annoying aunt, Dolores from the office, their ex-girlfriend’s perpetually cranky ex-rooommate — who claims to have fibro but, in these people’s expert opinion, are really just whiners. Even some doctors are “skeptical” about fibromyalgia due to the absence of objective diagnostic tests for it.

Wikipedia describes FMS, commonly considered either a musculoskeletal disease or neuropsychiatric condition, as “a medical disorder characterized by chronic widespread pain and allodynia, a heightened and painful response to pressure.” Others cited symptoms of fibromyalgia syndrome include debilitating fatigue, sleep disturbance, and joint stiffness. It’s noted that fibromyalgia is frequently “comorbid” with depression, anxiety, and PTSD. Most important to a diagnosis is, however, the 18 Pressure Points outlined by the American College or Rheumatology’s criteria — specific tender points on our bodies that are painful to touch and, in my experience, start throbbing whenever you haven’t been managing your situation properly. There is no “underlying common cause” of fibromyalgia and there is no cure.

Now it was on me, now it was also mine.

I went back to the dorms and crept into Emily’s room and sat on her bed. “They gave me medication.”

“Oh my God, how do you feel?” Emily said with an urgency that surprised me, because she’d been napping when I walked in. She knew that I had a lot of pretentious holier-than-thou feelings about psychiatric medication. But who was I? My body had just fucking turned on me! I thought I knew what it was like to have a body and suddenly I was somebody remembering that feeling, screaming inside a carcass. Clearly I didn’t know anything about what should or shouldn’t go inside me. But also: my body had betrayed me. How could I betray it in return.

“I don’t know,” I said. Then: “Tired.”

Then: relieved.

I seem to have a habit of this — being against a thing because that’s the only way to stop myself from wanting it so much. Like being gay, eventually. Like needing anti-depressants, a few years after the day I am telling you about right now.

Fuck, I couldn’t wait to take my goddamn Elavil. That sounded awesome. I was so tired.

Second semester I took 18 credits, but left my morning blocks open and loaded up on evening classes so I could attend physical therapy three times a week at HealthSouth, which was in a strip mall one town over. I’d found it in the phone book.

“Usually women with knee problems like yours have hips like this,” the physical therapist told me, extending his hands far beyond his own narrow hips. “But you don’t! So this shouldn’t be too hard!” I frowned.

He focused on strengthening my quads, mostly, and I just enjoyed being able to exercise at all. I didn’t even mind doing the Stairmaster backwards while playing catch with a medicine ball. Plus every session ended with the electrodes I’d been so jealous of at MedSport.

See, the best way to combat fibro is to remain active. 20 or so minutes of standing still lights up the pain in my knees. Driving long distances makes my entire body throb. When I’m unable to get to the gym for a few days, the pain starts creeping up on me. I have to be active, I have to exercise, because if I don’t, I’ll get sick again. This also means that the physical therapist who’d advised me to stop exercising had contributed to, not abated, my rapidly progressing chronic pain disorder.

Whether or not Elavil was a placebo, it worked. I was able to fall asleep within an hour of laying down, usually, a big improvement over the four to five hours I’d gotten accustomed to throughout my life.

Not everything adds up, though. Like over time it’s been my wrists, actually, that hurt the most, and there aren’t wrists on the fibro pain charts. That’s just my body, I guess, and what it does, and maybe I’ll never know why.

Things got better. They did. I made more friends. Emily and I found a darkroom on the fourth floor and took it over for our own work. I stopped writing down everything I ate. As soon as I started dealing with the fibro and stopped thinking so much about what I was eating, my body returned to the place it had been before the fibro started, a mystifying element of this process I’ve yet to define.

The rheumatologist I’d seen retired a few weeks after I saw her, and the cost of getting a new rheumatologist was daunting, to say the least, so I dug around online and found MedsMex.com, where I could order the Celebrex dirt cheap. Emily and I moved into the NYU dorms for the summer — she had an internship because her Dad knew people. Nobody in my family “knew people,” so I couldn’t get an internship. Instead I worked at The Olive Garden, where I discovered after a few happy hours with the boys that Celebrex and alcohol are a mean combination, so I stopped taking the Celebrex. But the pain didn’t come back, I was okay. Now I manage it, now it is a thing to manage.

It’s been 13 years now since I was diagnosed, 13 years of living with a chronic pain disorder. 13 years of a stressful week at work being compounded by searing pain in my wrists and elbows, 13 years of crying throughout the last leg of a road trip due to the immense pain inspired by sitting still for so long. 13 years of designing my work and social life around needing enough sleep and time to work out. 13 years of feeling like I am burdening my partners with my special needs, despite their insistences to the contrary. 13 years of every unrelated pain earning fibro’s automatic double word score and knocking me out. 13 years of wishing all difficult things could be done lying down.

I’ve changed how I manage fibro and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome over the years — different pills, different exercises, different “home remedies.” I’ve been tinkering with a cocktail that hits all my bases, enabling me to sleep but also to be alert and awake, easing my pain without knocking me out. I moved to California three years ago, and marijuana is legal here, and that helps with pain management. Compared to the stories I hear of other people with fibro, I think I’ve fared about as well as anybody possibly could.

But yes, it’s also become another one of those things that not everybody wants to take seriously, one of those things about me that the world demands I assemble a narrative to explain. But working backwards like that doesn’t seem fair. I didn’t crush on girls in middle school, so I’m not queer enough. I always excelled academically, so I must not really have ADD. I’ve never been hospitalized for a suicide attempt, so I must not really have Major Depressive Disorder. What I know is this: these words gave me the tools to get better and be happier and live a more authentic life. Maybe not all of those words are the right words for what I am, but they’re close enough.

But this, above all, is what I’ve learned: The body is not meant to be known. We can try, we can try science, medicine and doctors. We can take pills and plot our pain on a diagram and count our calories and give our blood to experts for analysis. But ultimately nobody — no doctor, no book, no diagnosis — can trump our own experiences of our own bodies, of our own tender spots and our own trails of light, of what we do to feel better and what we avoid to avoid feeling worse. This is me, this is my body, and it hurts to live inside it most of the time, but it’s all I have. It’s all I’ll ever need.

Comments

This thing, where you keep having amazing articles where people pour out their soul onto the page and it’s so deeply personal and relevant. It’s becoming much more common in 2014 than ever before.

Keep fucking doing this thing.

This is an important thing.

“Keep fucking doing this thing.”

A-fucking-men! over and over and over again!

Yeah. What she said.

Agreed. Autostraddle has been lately (even more than usual), a really special corner of the internet, that feels secret and personal and lovely. I copy and pasted bits of this essay (ok, most of it) into emails that I sent to myself, each time thinking, “this is the most important/true thing I’ve ever read.”

The fact that that is not actually such a rare feeling here/lately is fucking incredible.

Thank you for this. So much.

“These words gave me the tools to get better and be happier and live a more authentic life.”

I’m going to repeat this every time someone tries to tell me a problem I’m facing is imagined or not very serious. Over and over and over.

I feel all of this so very much. I dealt with major neurological issues, eventually having to have brain surgery, when I was a kid (11, to be precise). And, in some ways, I remember the uncertainty and the pain and the worry so very vividly. But, at the same time, it’s all a blur. It didn’t last for very long (not even 6 months in total) and yet I know that it felt like an eternity when I was going through it.

But as much as my memory of that time in 2002 is foggy and uncertain, I do remember so very vividly the day that the pain came back. I was a junior in undergrad and I was supposed to be taking a mid-term and all the sudden I could barely walk or grip a pen. The next two and half years were filled with so very much uncertainty and pain and questions. But I think the one day that still sticks out in my head most strongly was the day that the head of neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins told me that it wasn’t my problems from when I was 11 coming back. That I had to start over. That he couldn’t help me.

I think I balled my eyes out for two days straight after he told me that.

The uncertaintly, the not knowing…at times it’s so much more painful than the actual pain itself.

I stil don’t know how I graduated from undergrad or got through my first year at law school because I was perpetually in so much pain, always high on tons of narcotics and other meds, and pretty much never slept. I don’t know how I physically survived. But I think part of it might be that at least I had answers. At least I only spent a few months in that vast and terrifying unknown.

All that to say, once again, I feel everything you wrote so very much. And I’ve been wrestling with the idea of loving my body, despite and through and even because of all its many issues. So thank you for, once more, exposing yourself in such an exquisitely painful and beautiful way to us.

I joined this site just so I could reply to this post.

When you said “It’s alienating to live with an undiagnosed illness”, it gave me chills because it’s so profoundly true. I was born with a congenital immunodeficiency, but it went undiagnosed until I was 24. I was sick my entire life, but nobody knew why. You go through all the fear and frustration of not knowing for so many years, and then you have to deal with the feeling of being a burden to your loved ones and try to ignore the looks they give you when they start to wonder if you are actually making it up. Alienating is the perfect word for it.

Though we suffer from different conditions, so much of what you went through sounds familiar. Thanks for sharing your story with us, and I’m so glad that you were able to get a diagnosis and the proper treatment. It’s good to have stuff like this out there…. so we all know that we’re not alone.

I totally know what you mean with people feeling like your making it up. I swear, when I was a kid, my brothers only thought that I said I was in pain to get out of cleaniing up from dinner. And there were so many times that I started to believe them….

I can definitely relate. My sister used to accuse me of wanting to get out of going to school or doing chores when we were kids.

During the end of my teen years I was admitted to the hospital on nearly a monthly basis for infections, but the doctors still didn’t know what the underlying cause was. it got to the point where my father would get angry with me each time my mom had to take me to the ER, because it was an inconvenience to her to have to sit there with me for hours and miss out on sleep and meals. It made me feel like such a burden that I started waiting as long as possible before asking to go to the hospital, hoping that the infections would resolve themselves or that it wouldn’t get too serious. One time, I waited too long and ended up septic and in renal failure because I didn’t want anyone to be mad at me. Though I understand why they got frustrated, it still sucks when they take that frustration out on you as if you can do anything to change the situation.

Riese. You talented gifted writer..your work ks amazing as always. Thank you for always sharing and letting people know they are not alone with their experiences.

Thank you for writing this.

thank you. I hope you have a lot of spoons today.

Riese tears are running down my face as I write this.

I have fibromyalgia and lupus. It took them years to diagnose me. My illnesses almost completely destroyed my life, at some points nearly killing me. They took friendships, education, credibility and years of my life. I was told I was a liar, a hypochondriac, even that I had Munchhausen Syndrome.

I don’t remember anything from 2008 and 2009. Memories are gone, replaced my a fog of pain and frustration. But I’m gradually picking up the pieces, I’m taking control of my life and making it what I want to be. A-Camp was a huge piece of that process and I want to say thank you again for allowing me to have that experience.

And thank you for writing this piece. As you said

‘But ultimately nobody —

no doctor, no book, no diagnosis

— can trump our own experiences of our own bodies’

Which is exactly why these stories need to be told, these experiences shared so thank you for starting the conversation.

And look, now tears are running down MY face reading your comment. I’m so glad you were able to figure it out and take back control of your life, but so sorry you had to experience that.

Thank you for writing this! I can’t imagine how hard I would find it to be so honest and then to leave it out here for other people to find and read.

You mentioned something in your state of the union about becoming too aware of the audience… this is the type of piece that made me love autostraddle in the first place! It’s also why no matter whether I outgrow it or not, I will always support it for all the other people who still need it, as much as I did then. Basically I really want you all to be as “weird as you really are”, because it’s awesome and kinda unique for something as large as autostraddle.

Oh my God, this is just what I needed. Dealing with being different and having my needs based around that can be very lonely at times. But just knowing that there are others out there, who deal, who survive, who thrive, makes it easier for me. Thank you so so much for writing this, from a gal who lives her life in acronyms.

I have a journal entry from my freshman year of college when I finally admitted to myself that I couldn’t keep pretending that I could manage this pain, that what I was feeling was normal. When I started hurting more, when no amount of sleep was sufficient, when my depression got bad, and I admitted I couldn’t keep pushing myself. And what a relief it was to have a name, to know that it wasn’t all in my head, that it wasn’t imaginary, and because it was real, I could manage it, I could do something about it other than pretend it wasn’t there.

I related to all of this so hard. Thank you Riese.

This is … Important. Thank you for writing it, Riese.

I recently did a rheumatology rotation and found your article beautifully written and worth the read. What i picked up from my rotation was that lack of sleep is one of most important factors in fibromyalgia. Because of psychological stress/pain your muscles are more contracted than in other people, there’s more tension. This constant tensity takes a toll on your muscles, just like when you run 20km and your quadriceps hurts. Sleep is important because it allows your muscles to rest and regain strength. However, if you can’t sleep or if the quality of your sleep is bad, they can’t heal and the cycle begins: stress/pain-contraction-tense-pain-no sleep. So the idea is to break that cycle through better sleep :)

I wish you all the best and hope that your way of coping is working.

I love you for this. While so much of this felt like reading my own journal, other parts sounded like my wife’s life. She suffers from a chronic pain disorder called complex regional pain disorder, on top of fibromyalgia. It’s been a difficult road, and she is still struggling to find treatment that works for her. While parts about sleep, and dysfunctional relationships with food and exercise, depression and self injury sounded so much like myself.

Thank you, for your honesty and openness.

This post, as well as the one yesterday, both absolutely floored me. I couldn’t think of anything witty to say in response to “How “L Word” Internet Fandom Built Autostraddle Dot Com: The Oral History” so I didn’t say anything at all.

But, I really enjoy reading these heartfelt first person accounts and I felt that to read them both and gain something from them without letting my presence be known would be greedy and disingenuous. Thank you THIS MUCH for creating and curating Autostraddle into the thing it is today.

thank you for writing this. i have hypermobility and fibromyalgia so it’s nice to hear other people’s experiences with chronic illness

I have been thinking today about going back to the doctor about something I’ve been told is and isn’t there, or is and isn’t real, and now I can’t decide if you’ve convinced me to go or convinced me not to go. It’s been so good to read though, and I’m glad you’re finding a way to manage your symptoms. Thanks <3

Thank you so much for sharing such a great piece with all of us.

Thank you so much for writing this.

Thank you for sharing your story. I have had chronic foot and ankle pain and inflammation for so many years, but I only saw a doctor about it a few months ago. Mostly because I felt embarrassed, ashamed of my body, like this is something that only happens to people who aren’t physically fit, like it was my fault somehow. It’s still hard to tell my friends and family the truth- the reason I rarely go out socially during the week isn’t that I am tired. It’s that once I get home and sit down, the idea of getting back on my feet for another 3-4 hours is impossible. Or that whether I can go biking or skiing on the weekend depends on what kind of shoes I wore in the days before. The part about wishing everything could be done laying down- me, too.

“I wanted somebody to tell me how to be a person. Nobody did.” This. Always.

Thank you thank you thank you, Riese. I think you just helped me snap out of a really bad cycle of pretending everything’s fine.

Thank you for being so thoughtful, articulate and brave.

I battled with chronic pain for over a decade, so this deeply resonated with me. Thank you for writing this.

I really loved reading this, thank you.

About 2 years ago I had terrible muscle pains mostly in my arms but legs too sometimes. I was constantly exhausted to the point of tears. No one really believed that it was as bad as I said. I could hardly use doorknobs or open lids. It went on for almost a year before I found out that my Vitamin D was super low. My doctor told me to take 1000 IUs a day, it made it a bit better but not much, I started to take 2000. I got checked again and I was still far below normal. Now I take 3000 sometimes 4000iu of vitamin D a day. Thankfully it seems to have been the solution I needed. But if I forget it for a few days I can feel the pain creeping back into my arms.

“It’s alienating to live with an undiagnosed illness. You’ve got no clue how you’ll feel the next day, or what to do about it if you do. The future is fuzzy, the present is unclear. You’re waiting to find out what’s wrong, but don’t know who’s gonna end up telling you, or when.”

Oh man, I feel you so hard there. I currently have something going on with my reproductive system that means I’ve had awful periods ever since I started them. They started late, but were 28 days apart on the dot for six months, then I went 8 months without having one, then I was hospitalised twice in three months for the pain when I started having them every six weeks or so. The pill didn’t help, I just bled heavily for the three weeks on “active” pills, then it finally weaned off on placebo pills.

I’m still undiagnosed, and they’ve done every test under the sun (Side note: I had seven pregnancy tests last year and thirteen blood tests). Not polycystic ovaries, not ectopic pregnancy, not hyperthyroidism, not diabetes or polyps or fibroids. The only thing we haven’t tested for is endometriosis, and they’ll have to slice me open for that one.

I just… I feel you. It fucking sucks to be undiagnosed.

i also have to echo a big thanks for writing this.

undiagnosed chronic illness is not talked about enough.

i have had daily pressure headaches since last march-feels like i’m hungover all the time or like someone squeezing my brain as if it’s a basketball they’re trying to pop.

multiple mri’s & medications have lead to being on neurologists’ 4 months waiting list.

it’s scary & frustrating & i’m trying to not put my life on hold. thank you for this website and thank you for writing this. sending healing thoughts to you.

“and the world and I suddenly perceived my body to be a final product in need of care” — such a good way to put that.

I knew where this piece was headed as soon as I saw the image, and yet I still cried when you talked about the diagnosis.

I’ve been dealing with fibro since I was 15 – and that was back before anyone really had heard of it, so explaining it to people just earned me a bunch of blank stares and disbelief. Even now, half of everyone I mention it to doesn’t believe it’s a “real disease,” insisting its all in my head or that I can cure it with a positive/better attitude.

I dont have flare-ups as often as I used to, but when I do, I hate talking about it, especially with my girlfriend, because I feel like all I’m doing is complaining and being a burden. (Even though she says she doesn’t see it that way.) Basically, pretty much exactly you wrote. Its embarassing to talk abput sometimes; especially being young(ish) and dealing with “little old lady”-type aches and pains. This piece brought on all the feelings. All of them. Seriously, I can’t thank you enough for writing this.

I may not have fibromyalgia, but I relate to this so hardcore. Especially this part right here:

“I didn’t realize ’til we got the results back how much I’d been hoping for that to be the problem, just so that I would know what the problem was.”

That pulled a heart string, and then you just kept going. In fact there was so much to this I’m going to have to read it a few times over. This is so very important to life right now. Thanks for writing this, Riese. I needed the wake up call.

thank you for this. i remember going to my new doctor one day and talking about how my knees hurt and my elbows hurt and everything hurt. she looked at me and said, ‘you are too young to be in this much pain.’ after a decade of pain (and the things my parents said to me about it), someone finally stopped and told me what i was feeling was wrong and couldn’t be solved by working out more. i didn’t believe the fibro diagnosis at first, but having a diagnosis is so, so, so very important in empowering us to move to the next part of our life. and finding others with similar experiences moves us even more.

so thank you again for this. you’ve shared a couple of very personal stories recently, and i thank you for being so open. it’s quite powerful reading your words.

w/r/t the eating and exercise bits: This caught me in a place where I’m finally admitting to myself that I have an eating disorder. So thank you.

Thank you so much for writing this. This resonated with me so intensely, I had to take breaks and do things in other tabs periodically to keep from being overwhelmed with Feelings. From the eating/exercise issues to the misery of undiagnosed chronic illness to the dealing with an actual diagnosis of fibromyalgia, I’ve gone through all this stuff too.

My particular adventures with these issues differ from yours in a lot of key ways, but it’s still so familiar still. It’s nice not to feel alone, although I’m sorry you’ve had to deal with this stuff.

Thank you, thank you, thank you for writing this. I’ve been dealing with chronic pain for a while, but didn’t start feeling bad enough to see anyone about it until about 6 months ago. Since then things have gotten progressively worse and I still don’t have any answers. It’s exhausting and frustrating and overwhelming and scary and all of the things you said. Part of me desperately wants a diagnosis just so that I have a name to put to the pain and fatigue I’ve been experiencing and the validation that what I’m feeling is real. At the same time, I’m scared that I’m going to finally get a diagnosis and be told that I’m going to continue to feel worse and worse or that there’s nothing that they can do for me.

At times this feels so big that I don’t know how to begin to deal with it. Knowing that other people have been in similar situations and survived helps to make it feel a little smaller and a little more manageable, so thank you.

I also have chronic pain and joint problems (different medical condition, but similar in certain ways) and relate to a lot of this. Thank you for sharing.

There’s really not much I can say to this except thank you, Riese. Thank you for your beautiful way with words, thank you for being willing to share so much of yourself with us, thank you for writing things that reach in and grab my heart in such a painful yet comforting way. You’re incredible.

<3 <3 <3

Omg, Riese.

Thank you.

I was supposed to work a measly three hours this week but I collapsed in kitchen this morning and so have called in sick to the only three hours I was going to leave the house. It’s been eight years since I was diagnosed with CFS and I am finding my inability to function increasingly terrifying. So I needed something like this article today. Perfect. It was really moving to be able to read such an honest account of your experience (I can relate to more than I really want to) but also to see someone as inspiring (and overachieving) as you admit weakness, frustration and hope.

This was incredibly honest and very well written. Thank you for your words and for sharing a part of your story.

I’m I day late to comment, Riese, but I love this. Thank you for writing in it. I wrote about how much I loved this piece in my journal yesterday, but then realized I didn’t tell you how much I loved this piece.

You’re so strong and brave, Riese, it really is an inspiration. Thank you for sharing this wonderful piece with us. You are truly the voice and heart of Autostraddle, and while I love every person who writes for this site, you will always be my favourite.

You’re my hero Riese, for real.

P.S. So excited to see longform stuff on AS!

Just sitting dumbfounded at how brilliant this is, as always.

(Black)Heart you forever. <3

Thank you for writing this. I have to adapt my life around chronic conditions – including some that took years to diagnose – and really appreciate hearing from others with similar struggles.

Also, this was a very rich piece. Thank you.

Thank you for sharing this part of yourself, I’ll carry it always in my Runaway Heart. (Also, Sharon is my favorite character on BSG, so I loved that you mentioned her and her identity)

(i’ve secretly loved sharon more than starbuck most of the time)

(me too)

I have a rheumatic illness, and often feel tremendously lonely about it.

I was also undiagnosed for years. Didn’t even realize I had all these experiences before I read it.

Thank you.

man, this made my heart hurt because your experiences with fibro reminded me of my sister, who was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis in her late twenties right after she took me to nyc for college tours. it was so difficult for her to walk anywhere during that trip but she endured the overwhelming pain for me. same as fibro, there’s no common cause and cure for RA, which is especially frustrating. i think now my sister is finally coming to terms with living with RA and figuring out what’s best for herself and her body but it always breaks my heart when my sister reports back from a doctor’s visit that this and this medicine didn’t work, that she has to drive to a different town four hours away to see the right specialist, that she’s drowning in medical bills, that she can’t move her arms above her head so she can’t do things like brush her hair or just seeing her super frustrated. all i can do is giver her emotional support and give her elbow/arm/hand massages which always makes her happy.

I’m very sorry for your sister

It might be a good idea to try homeopathy if she feels like it, it helped me a lot

Thank you so, so much. I’m trying not to cry. I have asthma, irritable bowel, OCD, restless leg syndrome, and apparently the fact that I have trouble sleeping and my body hurts for no apparent reason “is just life.” No medical professional has ever taken the time to explain any of these to me (except OCD), and they are all invisible, except asthma to a degree. My experience may not be as severe as yours, but that just means I get embarrassed because of these mystery symptoms people can’t see and so ascribe to hypochondria. And to make matters worse, OCD and hypochondria often go together, so I doubt myself and my own body. Do I really feel like this or am I just crazy? And other people get frustrated by symptoms they can’t see and don’t understand, especially since the triggers aren’t constant.

I really appreciate you writing this. Our stories aren’t the same, and it sounds like your problems are a little better managed than mine (I still don’t have a working system). But reading what others have gone through reminds me I’m not alone.

Thank you for writing this, Riese. I don’t have the same pain that you do, but I am currently going along undiagnosed, and it hurts.

I could re-quote this whole thing with one giant YES, but in particular there was this part:

Gah, the blockquote didn’t work the way I thought it would, so I’ll just put it here again without frills:

“What I know is this: these words gave me the tools to get better and be happier and live a more authentic life. Maybe not all of those words are the right words for what I am, but they’re close enough.”

1. Thank you for writing this. I loved it.

2. Thank you for referencing BSG

3. Thank you for referencing Panchero’s.

Thank you so much for this.

Also, this is exactly the thought I’ve been trying to articulate for the last year and a bit. Thank you again Riese

At 19, everything seems potentially permanent and therefore terrifying — you’re between childhood and adulthood and clues shoot from all directions about what that adulthood might look like.

As an eighteen year old who has been suffering from chronic fatigue and fibro since I was eleven, as well as depressiona and anxiety, thank you for writing this.

Knowing that the person who has created autostraddle, who began such an awesome community has and is still going through this gives me that little bit more hope that I’ll be able to achieve something as well.

you’re so much and you can do whatever you put your mind to, grasshopper. i’m glad this essay helped you believe that very true thing.

Thank you for writing this, Riese. I hit the low point in my eating disorder at 14, a couple years before I had enough awareness of myself to put together a couple hesitant words about my sexuality (I might be bi …). Your post brought back the feeling of trying so hard to be good: Skinny, smart, straight.

When you’re used to suppressing something as basic as your need for food it’s relatively easy to push aside your fascination with the music video for Whenever Wherever, or the way you feel about your friend Hannah (and her stupid boyfriend).

I had to give up control, and concede that I was hungry for things that weren’t good (at least not by the metrics I was raised with). I started to eat again–anything I wanted–and not count the calories. Eventually I found my hunger. I knew when my body needed food because I had started to listen. It wasn’t long before I heard that part of me yelling out “The way you feel about Shakira is suuuuper gay.”

I used to use exercise in the wrong way (for control), but now eleven years into recovery for anorexia I exercise because my body wants it the same way it wants food and sex. I listen now.

Anyhow, I don’t have a point other than I hear you, Riese, and I really appreciate what you’re doing with Autostraddle. Thanks again for sharing.

I love your work Riese.

I love that you are generous and courageous to open up and share your experiences fibromyalgia, depression, sexuality, wanting to control your body at least, your Dad’s death, and your determination to manage pain and loneliness when you had no diagnosis, when you were alienated, when you felt you weren’t cutting it as you thought you should as a young adult in a world full of achieving, healthy, ?carefree?, wealthy, privileged, go-getting adults around you demonstrating their ease with being young and adult.

I love your determination to keep on trying to find your definition of your quality of life, on your terms, no-one elses, and your realisation that you define your body, its health and health challenges, with your terms of reference. That you know that your body is a lived experience, so it is therefore a free ranging, free style, creative experience that can be chosen, lived and validated by you by each moment. Your transparency in sharing your pain, your challenges, and your ongoing management of these issues in your life is so important to us as an audience. Your sharing of your lived challenges and pain makes it easier for the rest of us to share our challenges and uncertainties and the tolls that these things take on our moods and feelings of being supported, or not being supported. You inspire because you choose to share your intimate challenges and pain. Thankyou thankyou thankyou.

Thank you thank you thank you. I don’t have this, I have something else, but I went undiagnosed for three years until last fall, up until then I thought I was dying of some invisible futuristic cancer and dear god thank you.

I want to thank all of you for your comments and sharing your stories here, really, so much. It means so much to me and makes telling the truth so very worth it. I’ve been reading these over and over since posting the essay, thank you. <3

I really needed this now. I turned twenty less than a week ago and I’m currently dealing with fibro, an auto-immune disease called Behcets, and so-far undiagnosed pain in my hands that has forced me to drop out of college and possibly give up on my life-long dream of being a fashion designer. The pain is bad enough that even typing hurts, and I can’t hold a pencil or scissors. I feel so alone and alienated, even with good support and some communities online. Reading about other people who deal with chronic pain and illnesses helps, at least a little bit.

riese, thank you for doing that thing that you do where you put words together that accurately describe something i’ve felt. this was great.

Thank you, thank you. I am going through my own process of grappling with my body- I’m a professional acrobat, and my body just started falling apart a year ago, first one joint and then another and then illness and then etc, and physical therapists don’t seem to *really* know why they’re doing some of the things they’re doing, which is terrifying… and I’m not really sure who I am anymore or what to do with this body that feels like it’s trying to buck me off sometimes. These feelings you describe in this piece resonate with what I’m going through, so much. Thank you.

Thank you. I have no other words.

Late to the party, but I still wanted to say thanks for this. As an Ann Arborite who just finished grad school at U of M and has been dealing with fibro since high school, this was almost a surreal read, but very much appreciated.

Thank you. So much.

So this is almost a year late, but Riese, some things you say are SO me that it scares me, especially since I search and search for words that describe me that other people have felt too…and, wow. Thank you.

“But working backwards like that doesn’t seem fair. I didn’t crush on girls in middle school, so I’m not queer enough. I always excelled academically, so I must not really have ADD. I’ve never been hospitalized for a suicide attempt, so I must not really have Major Depressive Disorder”

UGH. I am 34 and still have no fucking clue if I am gay or not, but I know I didn’t crush on girls in middle school. I just spent well over a month in therapy with my therapist trying to convince me I am very depressed, but still have trouble reconciling that, because hey, I have never wanted to commit suicide! Sure there was that one time period where I wished I was dead every day, but not the same thing!

Also–who knows if you will ever see this, but if you ever feel like answering either publicly or privately, do you think your mom being gay as well sort of hindered your coming out to yourself? My mom came out when I was 23, and I have actively tried not to be like her most of my adult life, and I sometimes wonder if my confusion is more complicated because of that. I would think that it would be easier knowing my mom would be accepting and she broke the mold for my whole family if it does turn out to be true…but still.

Hi hi! I just saw this and 100% the answer was YES, for sure. I think I would’ve figured it out many years earlier had that not been the case — people always assume that that should’ve made it easier, but definitely the opposite, just like you said. (i talk about it a little bit here)

(also thanks for the kind words about my words!)

OMG, Riese! I read that other article you linked to, and I am 100% sure I’ve said this EXACT line about me and my sexuality with my mom:

“Because of my Mom. I just can’t give her that.”

YES. I do not want to give her something so vulnerable and such a big deal to my mother, because it would inextricably bond us in a way I truly do not want. Bonding over running, fine. Bonding over sexuality? No.

oops, well over a year late, but whatever.

Thank you

I’m still reading this article. I have chronic migraines and a “tentative fibromyalgia diagnosis” from a neurologist, and feel forever in limbo — the treatments for the two are nearly the same, so does it matter whether or not I have the f-word?

But this part resonates the most:

That’s the thing about getting sick the way I got sick: nailing it down. Sometimes it seems like the story started when I was 14, or maybe even earlier. It gets mixed up with other vague diagnoses, and other parts of myself I learned to name months or years after I started to feel them, like being gay, like depression, like ADD, like being a “writer.” I know that I am these things, but I don’t know why, and I don’t know if I tell stories like this one to convince you that they’re true, or if I’m the one who needs convincing.

I comb through my fading memories again and again, trying to reason out my emotions and make connections and remember how I felt 2 years ago, 10 years ago, longer, as if it would help if I could only better grasp the timeline of my pain.

Thank you for writing this.

I just started my own blog as a precursor to an autobiography on my pain experience. You may find relatable posts on my blog. It’s Life Colored by Pain in WordPress.com.

I loved yr post here!

[…] Everything Hurts All The Time – I ate Slim-Fast bars and cucumbers all day and at night I ate cookies … I drank half a bottle of bubblegum cough syrup every night to get to sleep, and popped workout pills and guzzled Diet Coke to stay awake the next day. I felt like everything was … […]

Thank you for writing this.

(I know this is an old article, but – I first read it maybe two years ago, and I was diagnosed with fibromyalgia two weeks ago, and “Now I manage it, now it is a thing to manage” has been the thing rattling around in my brain that sounds most like a way forward, so. Thank you.)

[…] is the year I got sick. I turned 19 a few weeks into my first year at University of Michigan. I was a sophomore but lived […]

thank you for this. man, i felt it so much.