trans*scribe illustration ©rosa middleton, 2013

On March 22nd, I paid a dude to knock me unconscious, peel back my face, and cut out big chunks of my skull and jaw. He was surrounded by nurses, which is always a good sign, and I have his solemn word that he went to grad school. But that’s what happened. That’s what I spent the better part of five months making sure would happen. It’s a surgery that I think of as the final component of my transition, a struggle to claim and assert a female gender identity spanning many years.

“Facial feminization surgery” (FFS) is a subspecialty of transgender medicine drawing from cosmetic and reconstructive oral, dental, maxillofacial and otolaryngological (ENT) surgical fields. FFS describes any procedure(s) performed on the head and/or neck in order to increase the likelihood that their owner will be “recognized as female” by observers, including and especially herself. You can remove bone bossing and cartilage outgrowths caused by sustained exposure to testosterone and augment soft tissue features, such as facial fat, which have not responded adequately to HRT. Some of the techniques used for FFS are subtle and borrowed from routine cosmetic medicine, like facial fat grafting and rhinoplasty. Others, such as brow reconstruction, are more aggressive and incorporate the most sophisticated tricks in the modern surgical playbook. FFS isn’t really about getting a new face – it’s about getting the face you would have been able to take for granted without that unfortunate first go at puberty.

While FFS tends to be “beautifying” and can make it easier to walk among the mean girls, morons, and psychopaths who litter the Earth, these are fringe benefits. People get FFS to treat gender dysphoria, a pervasive, limiting and even life-threatening form of discomfort experienced by transgender people.

This model isn’t perfect, and doesn’t fit everyone’s experience, but it’s helped me understand a lot about myself, and speaks to why I pursued FFS. As a child and young adult, I’d stare at my face in the mirror every chance I had and have no idea what I was looking for. These things would happen, I’d realize that they were at least a bit unusual, and I was left to figure out what the hell it said about me. It wasn’t fun, and I kept it to myself.

A few months after college graduation, I had one of your textbook near-death experiences and decided to grow up. Learning about FFS was one of a few things that helped get me started. I’d begun reading about gender reassignment, and saw a few of the classic examples of aggressive facial reconstruction. I had never really dared to ask myself if I would want something like this, it had seemed out of reach in some obvious, fundamental way. Allowing myself to think otherwise was like flipping a switch. I was still terrified and thought that I was almost certainly going to die, but it was impossible to take back. It was what I needed to do. So I did it.

I “went full-time” eight months ago, almost two years after deciding to transition. It was better for me than I’d ever dared hope, and fixed problems I didn’t even know I’d had. I actually knew what good mental health felt like. On the very same week that I’d made it all legal, I landed a new job. Not only did this let me escape my second layoff in two years, I began working immediately with new people. These weren’t just good coworkers, they were people who hadn’t known me as a guy, or worse, as a ticking time bomb of sensitivity training. I was given my first managerial position and charged with coordinating a small army of volunteers. I became a published author. I was settling into a life that felt like my own, and my voice and confidence improved rapidly.

Many of the compulsions, neuroses, and anxious or painful feelings I’d come to associate with my gender dysphoria had faded out of even the background of my life. My face had improved, but it remained a source of anxiety and distraction, even on good days. HRT had helped a lot, but it has limits. There isn’t a pill made that can change bone structure like that. Every single day, I had moments where my face would make me feel insecure. I’d overcompensate in ways that left me feeling embarrassed and depressed, and often found myself distracted from people I cared about.

In some ways, it had gotten worse: I hadn’t liked being a guy, but the world accepted it and my face fit into that. That obviously didn’t help anymore. I had a year until I would be learning medicine, in a new city, with new people – I wanted to give it everything I had. I didn’t want to spend every morning in Chicago fighting my reflection to get out the door. If there were ever a good time to get major surgery, this would be it.

My doctors were supportive, but they could only tell me so much. There were one or two names half-remembered, promises to “look into it” for me. That chicken came home to roost months later, as a jarring email from the head of the local plastic surgery department. Dr. B wrote to reference one famous guy – the father of the FFS field, more or less – and declared that while he’s “never done much of this, really,” he would “probably be the next best option” if the Big Name were unavailable. Well shit, doc, that sounds like a plan! Why don’t you just come over, hit me with a 2×4 and we’ll get to cuttin’.

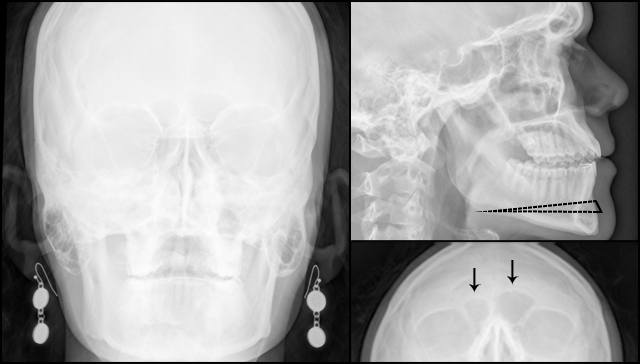

I collected names from web directories and journal articles, and cross-referenced them exhaustively with 7-10 of my friends who’d had FFS procedures ranging from minimal to highly aggressive. (I’d helped moderate a small online forum, and had stayed in touch with trans people all over the world.) I drove downtown during lunch one day, rubbed off my makeup, peeled back my hair, and had a photographer document my features at their most exposed: hairline, brow, thyroid cartilage, chin, and jaw.

My pictures went out with a short letter, walking through who I saw myself as and how I felt about my face as best as I possibly could. I made sure to stay positive – I liked my severity, my cheekbones, my close resemblance to my mother and younger siblings. I tried to explain what worked and what didn’t. “Passing better” would be nice, but I knew damn well that I was beautiful – the problem was that my focus and confidence were at the mercy of lighting, cosmetics, and a charitable mood. Reading these old letters, I’m struck by how much I had to worry about. I wanted to do this once and to have that be enough, forever. I had that unthinking fear of “excessive plastic surgery” like the paparazzi were just around the corner. I didn’t want to lose myself, I didn’t want to be a fucking Barbie doll. A couple of very high-pressure paragraphs, but it turned out alright. My friends insisted, “these guys are used to way worse.”

My friend Eliza Gauger signed on for mock-ups and aesthetic support. Eliza and I had met through unconventional public health outreach work, but she’s also a killer artist, model, dancer, and the last person you want to cross in the dead of night. We both understood FFS as a science developed to produce conventional, Western, cis-passing beauty. That isn’t necessarily bad for me, but it’s bad for plenty of other people and recognizing the implicit bias in the field is kind of disturbing. It seemed important to understand what these changes meant to me, and to other people, and why. Some of same cultural filters applied in other STEM topics are found here. It’s all good when you’re asking what to cut and how to stitch it back up. It’s less convincing to say that you can atomize the face and collect statistics on modifications of its components and come up with reliable aesthetics. I think it would be a fine thing if plastic surgeons were to pay artists lots of money to interrupt them during consultations, don’t you?

I worked through my list. One of the famous names had seemed like a good option, even if his approach – “I’ll list every single procedure I can think of that would help feminize you, just pick the ones you want” – made my skin crawl. I asked one question too many about a technique he’d developed and recommended to me, one too many about insurance, and his people stopped talking to me. It was as simple as that. Another charmer gave me two sentences: “My colleague, Dr. Q, can do the surgery. He recommends jaw and chin reduction.” Another surgeon seemed to catch on that I was just a bit neurotic. I’d approached him with a plan cobbled together from previous consultations and he started to pick out trivial aspects as “risky” or “unusual.” Fortunately, these were things that I knew were bog standard in the FFS subspecialty, like combining a brow reduction and hairline repair. It’s the same fucking incision! A similar drama played out over chin and lip procedures. He used every chance he had to suggest that other surgeons would turn me into a circus freak. I’m convinced that he was trying to scare me into working with him. It was horrifying.

I wrote Dr. T while he was performing charity surgeries in Eastern Europe, and we began corresponding extensively by email. He was finishing his training before inheriting a well-known practice in my area. We got along well: Dr. T was the first and only surgeon I’d contacted who would directly connect his advice to the goals I’d expressed. I’m not sure that anyone else had even talked about family resemblance, not even to tell me if I was worrying about nothing. He was also the most willing and able to have a full technical and aesthetic discussion about his recommendations. It was some of the Bill Nye experience I’ve chased in my academic and professional life.

Dr. T had started with the “rule of thirds.” When a face is divided into vertical thirds of relatively equal height at the lower brow and just under the nose, it tends to be read as more feminine. Women in my family have powerful chins, but androgen exposure had pushed things a bit far in my case. A reduction in that area was one tool for restoring proportionality. Something about the lower half of my face had bothered me, but it had been hard to figure it out. This idea sat well with me. Jaw reduction is a more aggressive approach, with a longer recovery.

Other recommendations were extremely conservative, but clever – Dr. T mentioned that fat grafting tricks that might help with my brow, among other areas. While it’s true that fat grafts are less invasive and can look great, they’re difficult to make permanent. Whatever I did needed to stick, and my brow bothered me.

For the brow, you have two basic options: reconstruction and reduction. A simple brow reduction is limited, because you cannot expose the patient’s frontal sinus. The size of this cavity varies dramatically, and it is sometimes even absent, just like the bossing that covers it. But it needs to stay intact, and that’s made aggressive brow reconstruction the shining jewel of FFS techniques. There are multiple variations, including several that call for removing the entire bone and grinding it down on a table before grafting it back. With rare exceptions, these are techniques that are universally recognized as sophisticated, safe, and effective.

This is where I’d been discouraged. I had assumed my options were generally safe, and had seen the degree of change that was possible years ago. I wouldn’t mind something radical per se, but I wanted to talk about it. Unfortunately, while the Great Men behind these techniques do genuinely beautiful, sophisticated work, they all seem to think that theirs is the only sane and effective approach for reduction. When I consulted with one such surgeon, he hardly seemed to care about matching the brow to the patient, even in the context of his preferred technique.

Dr. T’s response indicated that he felt competent with at least one of the aggressive reconstruction techniques, but he’d reached similar conclusions. It does make people look very different. It was up to me, but from how I’d described myself, that didn’t seem like what I was looking for. And no, really, it wasn’t. Eliza had made a mock-up of combined chin and simple brow reduction that was kind of astonishing to look at, and Dr. T was willing to sign off on its accuracy. That would do it.

A reduction genioplasty (chin shave) via osteotomy and simple brow reduction/brow lift would be the major components of my operation. I also insisted on a lateral hairline advancement. While Eliza and Dr. T had correctly noted that my central hairline was well-positioned and the sides were almost totally unnoticeable, it was exactly the kind of thing that drove me crazy. Every gust of wind, hairpin, itchy spot, tie, or hat disturbed the thick horns of scalp running up both sides in a classic “M” shape. I had to style my hair differently to compensate, and rearrange it carefully when I tied it behind my head. It just fucking sucked, and like I said – same incision.

I’d waffled on reducing my thyroid cartilage. The “Adam’s apple” is such a stereotypical focus when people talk about trans women’s bodies. Mine really wasn’t prominent, but I wouldn’t miss it either. I hated the idea of getting cut more and risking my hard-earned voice just for other peoples’ benefit. I slowly came to feel that it was something I looked at, and did bother me a little, and it might hurt to have that be the last thing that got to me in this way. It went on the list.

So basically, I was ready to go. Then other people happened.

Comments

you. are. stunning. like, jaw-dropping. your strength and inner beauty are also awe-inspiring. what a woman, holy moly.

“and have hands that would make Lana Kane blush.”

I’m dying, that is so funny! You look wonderful. Thank you for sharing your story. :D

Thank you so much for sharing your story – it was an amazing read.

And I have to second Sass, you are crazy beautiful. I would kill for those cheekbones, you heartbreaker!

All the very best for the rest of your recovery

Fascinating. Thanks for this perspective. I especially liked your funny one-liners (“I am my Goth friend”; “swarm of WASPs”), the way you kept your language technical, and, most of all, how your sheer happiness is palpable. Congratulations!

Yes! These are some of the things that I loved. Pretty amazing. Thank you for sharing this with us.

Love your happiness, strength and sense of irony/humour. More power to you and glad it’s past now.

Every bit of technology that gives you an edge in this grimdark is welcome ;)

This is such an amazing piece. You are so strong. What an inspiration!

I am moved.

This is a beautiful story and you are an incredibly beautiful woman, thank you for sharing!

Awesome story. I like how you can see the earrings on the X-ray!

ahahaha, thanks, I love that part too. I even asked the radiology tech “uh, dude, should I take these off” but SOMEONE had a sense of humor sooooo

The best part was I honestly had no idea they’d show up on the film until I had to get them burned to a disk like a month later. “Oh right, I was wearing those, oh man”

I’m planning on getting ffs also, been on hormones almost a year now, and I was wondering what your insurance company was because most of them have language in their policy that specifically discriminates against transgender people.

Well, as per my post below… my policy actually does have language that should cover FFS, and my insurance reps told me and my doctor, repeatedly, that they would cover it, and now they’re refusing to. Exclusions like you mention are illegal in my state, but they’re still all over peoples’ policies, because health insurers will not care until someone makes them care. Specifically, someone who’s dealing with serious medical needs and has a lot more on their plate than “spend months sending calm but firmly worded letters to every tom, dick, and harry at wellpoint”

It’s a truly ghastly system, for pretty much everyone, because everyone gets sick. I hope to live to see it burn to the ground.

Excuse me Olivia … but don’t you mean Transsexuals which actually belong outside of the transgender suffer from Gender Dysphoria. Most transgender people do not suffer from this precise medical condition. There are 14(+) sub-categories under the transgender arena and it was our so called supporters from the LGB community who threw Transsexuals into the mix of those in the transgender box back in 1999. Though I have many transgender friends even they know the differences between being transgender and Transsexuals who suffer from the precise medical birth condition called “Gender Dysphoria”. There are tens of thousands of us Transsexuals who refuse to be placed in the transgender box so as not to be confused to be CD’s, DQ, GQ’s, GN’s GV’s, TV’s, She/males, or any of the rest of them who do not suffer from our natural birth affliction. I have needed and gone through FFS as well including having had Gender Corrective Surgery (GCS) which used to known as SRS and still is by a few clinics out there. If you seen a Trans specialist and told him that you was transgender, they would first ask you of which category so he could determine the seriousness of you needs. I was a Transsexual prior to my correction and was never referred to as being transgender in any of my medical documents or letters. I hope this will be an enlightenment and of some use to you in better understanding yourself.

I am aware of the ideology you’re putting forward, but as “one of the freaks,” I’m not terribly inclined to adopt it. You are simply mistaken about the categorization you reference and what you imply about it determining the “seriousness” of my needs is inaccurate and offensive.

How you see yourself is entirely up to you. As for myself, I am aligned to no small extent with the framework delineated in the most current standards of care. They are freely available to you if you have any confusion as to what is expected of providers in this field.

As someone who is transsexual and identifies under the transgender umbrella (i.e. doesn’t identify with the gender/sex assigned to me at birth), I see no point in drawing such a distinction in coverage. I don’t think it’s any more likely that insurance will cover it for me if I advocate against allowing it for others who don’t have precisely the same (but have at least some of the same) gender and body feelings as I do.

Basing treatment on proving how bad you want it, and establishing a corresponding hierarchy, is drawing a pointless distinction. It’s derived from patriarchal gatekeeping in the medical community, and I refuse to participate in it.

Just to be clear – I am glad to hear that you are able to have your identity preferences accurately reflected in your medical documentation. This is as it should be, and is consistent with the standards of care.

What you have to say about the gender dysphoria of people who are not you is not accurate, and it is not particularly kind. People suffer from gender dysphoria in a variety of ways, the necessary treatment is extremely variable and personalized, and how people come to understand these situations will similarly differ.

Medicine must meet people as they are and treat their needs first and foremost. This is a sacred idea to me. You complain of being “boxed in” with “shemales” as if legitimizing broader experiences of dysphoria threatens and constrains you. That must be very painful for you to feel, but it simply isn’t true. We can all live with dignity and receive the care we need. Giving that to other people takes nothing away from you.

I don’t doubt that you fear a society which might accept Good Transsexuals but won’t accept Freaks. That scares me, too. But it doesn’t make that right, and it wouldn’t make it right or healthy or even tolerable for me to contort myself to some unreachable “normal” and hope for scraps from society’s table.

No one is forcing you to hang out and blast Jack Off Jill with us, but I’d appreciate if you don’t go around telling people that we are less worthy of medical care than you. Cheers!

“If you seen a Trans specialist and told him that you was transgender, they would first ask you of which category so he could determine the seriousness of you needs.”

…loosely translated, “some people deserve basic medical care, but I think most of you don’t, and I’m going to ground it in a ‘trans specialist’ backpedal.” Because almost every ‘trans specialist’ is white and male, that means women should ground their legitimacy in what white men say.

Wow, do you run the support group in this town?

I played the Good Transsexual I’m Better Than Anyone Else game for years. It was destructive, hurtful, and bordering on actively sociopathic toward people like me when I did it, and I don’t think it’s any different when someone else does it. That said, I’m really sorry that I ever did things like that, understand it might be unforgivable, and I will tell you that doing something about my internalized self-loathing around being trans helped. It helped a lot.

When you tell people they’re less worthy, you mark them as disposable. When you mark people as disposable and build walls to keep them out, you get how the “trans community” looks today.

And if you are the person who runs the support group here, can you quit leaving fifty-line hate comments on my blog? If you’re not, well, you’re sure channeling her.

This is super interesting. Thanks for writing it!

I still can’t help reading FFS as ‘For Fuck’s Sake’ though. Old habits die hard…

Thank you so very much for sharing this. You are an impressive and evocative writer, and I feel privileged for the opportunity to be your audience.

You look very pretty, I just wish I could look at “the results” without being flipped off or having you sticking your tongue out. We’re here to read your essay and learn about your experience, not to judge you.

“do you have any other pictures? I’d love to see a more neutral expression” would have been fine. Condescending to me about how I choose to represent myself and my passage through a very frightening, difficult experience is not. Sometimes I cope by being a shitty teen. It works for me. Deal with it, mom.

And look, it’s not that I don’t care what you think. I wrote this article mostly for myself, but I would very much like it if it could also be helpful, or interesting, or just entertaining to other people. If you, or anyone else, has follow up questions, wants to see less silly pictures, whatever, I’m all ears.

But I simply did not do any of this to look pretty for you. It’s puzzling and frustrating to be spoken to as though I did, particularly by someone who’s just read an article that was more or less designed to get that exact point across.

it’s cool how we can depend upon getting our fucking bodies policed literally everywhere, including on Autostraddle, in the comments of an article about FFS.

it’s also cool how you get sniffy scare quotes around “the results” like its just, like, your opinion, man

Wow you are reading that comment really pessimistically! Have a little more faith in your fellow straddlers! “The results” could just as likely (and I think more likely) refer to an informal results section.

I think that’s a little harsh to say that she’s policing her body and is scared of the results. Again, just my opinion.

In Gina’s defense, I don’t think she meant it aggressively. I think she was commenting that you are gorgeous, and then separately commenting that this is a generally supportive site and the default to defensive pictures isn’t necessary here. Anyway, that’s how I read it. Hope I’m not overstepping.

In other news, I found this article really interesting and it’s a story that I’m glad is getting out there. Thank you for sharing your experience, and I agree with everyone else: you look beautiful and your confidence shines through.

That is how exactly how I intended it, Jen, but clearly, whatever I said came out the wrooong way and I apologize to Olivia for any transgressions or boundaries I crossed. I’ve gone through FFS myself and know what a physical and emotional ordeal it can be, what a mountain it is to climb to be able to pay for it, and how life affirming it can be. Now I’m going to shut my mouth before I stick my foot in it again.

Thanks!

ack, I tried to reply on my phone and it got cut off after “thanks!” – I wanted to say that I appreciate you saying that and, you know, don’t sweat it :-) I’m glad to hear you meant it differently!

Thanks! Glad to hear.

That’s actually one of a few extra pictures that I’d included in my draft. It looks like the AS editors went with that one, which I’m cool with. But there was also a recovery timeline and a few other shots.

I didn’t take that particular series for the article, it’s more that trying to duplicate old pictures is kind of a thing I do. the “before” pictures were just from goofing around about a month earlier, cracked me up when I found them during recovery, and the rest is extremely inconsequential history. They were actually a bit of an afterthought. Like I said, I’m considerably less motivated to document myself these days.

I think the finger-up, tongue-out photos are adorbs, personally.

It seems to convey a giddy silliness that is hard won and well-deserved, AND it also says “fuck y’all” to anyone who doesn’t like it.

That’s my few cents, anyway.

Olivia, I send hugs, high fives and FUCK YEAHS. Thank you for this article.

oh my goodness you poor darling. what in gods name will happen to you if you look at a photograph of a woman asserting agency over her own fucking face, you know, in keeping with the rest of the article you didn’t bother to read, instead of conforming to the rictus of the Acceptable Woman as curated by Dr. Professor Gina from Pee Dee Ex

Thank you so much for sharing this journey with us. Not only is your story helpful and interesting, it’s also inspiring.

Another reason your story is helpful – I can share this with a friend who was trying to understand why some doctors and parents are helping young transgender kids who are pre-puberty to halt the onset of puberty until they were older and could decide how whether they wanted to transition.

My friend just couldn’t quite understand why that would be a desirable thing – this really helps clarify why something like that would be important.

100000% off topic but GIRL GIVE ME THOSE BROWS OFF YOUR FACE RIGHT NOW. You’re Chicago-based? Who’s your brow person?

I can’t tell if AS is letting me message you back or not, but just to clarify: eyebrow waxer, not browbone surgeon.

in other news I am a big dork.

ahahahaha oh gosh I was wondering the second I sent that, sorry. I go to M&M thread salon in union square, which is a really friendly and inexpensive family-run place that has gotten me kind of hooked on threading. But I’ve also been doing my own for, shit, almost a decade now, and tend to alternate depending on whether or not I feel like I’m losing the shape, etc. I’d recommend shaping them on your own, very slowly, like over months even, and then relying on a salon for clean-up :-) You said Chicago, though, right? Is threading a thing there?

possibly the dumbest i’ve felt all month and this has been a DUMB ASS MONTH

i feel like i usually have the shape under control (i am verrrrry serious about brows), and then i lose focus for two weeks and suddenly two sperms are having a cockeyed conversation on my forehead. my skin is super duper sensitive so waxing’s out, but threading’s supposed to be fairly gentle, right? and yes, it is a thing here for sure – an old roommate swears by a place not too far from Loyola if you’re looking for recommendations when you arrive

Thanks! I’ll have to ask :-) Threading’s always seemed very gentle to me, but some people I’ve talked to seem to have had the impression that it was very painful, so idk. It seems like any hair removal method is going to vary a ton from person to person…

chiming in to say that threading is pretty gentle compared to other methods– it can be painful at first for people who’ve never done it before or have a lot of hair to remove, but if you do it regularly, it should be fine for you. threading also allows for a lot of precision in shaping, so if you’re all about maintaining your brows, i think you’ll like it a lot!

source: i’m an indian-american girl, threading is like a rite of passage :’)

Olivia, thank you so much for sharing your story with us! This is the first I’ve read about FFS and I’m glad that your article was the introduction. The hints of unexpected humor were perfect. I would totally want to keep any excess bone, damn that pathologist! I am that person that still has all her baby teeth & kept all her wisdom teeth.

You look adorable in those last photos! I’m in awe of your cheekbones. So glad that you are more comfortable in your skin. Hope all your insurance woes are resolved soon (those fuckers).

This article makes me ambivalently happy and sad at the same time. I am so glad for you that the facial reconstruction surgery helped you to see yourself as you do in your mind’s eye. I am so glad that you recognize yourself as beautiful, in spite of whatever the world and even loved ones may say to your face (because you are indeed beautiful).

I wish that my friend Kate had had your confidence, or that she could in some way see herself as beautiful, instead of as a monster. Her family and the world convinced her that she was a monster because she was born intersex, and then transitioned from the sex arbitrarily assigned to her at birth. Because of that conviction, she committed suicide the saturday before last.

It makes me wonder what can be done to help make trans* people feel ok, to feel less like suicide is the best option. Her death started up a discussion about whether transitioning led to her death or if not transitioning fully led to her death or what. About whether transitioning to a different gender presentation is enough, or whether SRS is necessary to feel complete. These are of course intensely personal questions

I am so, so sorry to hear about your friend. I think that the questions you raise are less difficult than you might first imagine. In fact, you nailed it in your own words. People think they are monsters and that their lives are not worth living because they are betrayed and rejected by their families, friends, and society. That’s what kills trans* people, more than anything. How you interpret your pain is not set in stone. People are not born thinking that a congenital defect (with respect to those who see their difference otherwise) makes them a monster or robs them of any life worth living. They have to be taught that.

I don’t know if gender dysphoria might still be fatal in a world that didn’t oppress trans* people. I think it would still be a tough thing to live with. But I can say personally that it has never made me feel so worthless, doomed, or ashamed as internalized stigma.

Small note – I would suggest you reconsider the idea of “transitioning completely,” if you meant to imply genital reconstruction as a “complete” or “finished” transition. Everyone has their own understanding of what is complete for them. Some people need some surgeries, some need others, some don’t need any. Sometimes it can change as people grow and develop throughout life. There is no “enough” that fits every trans* person, and peoples’ assumptions about this can really injure us.

“People are not born thinking that a congenital defect… makes them a monster or robs them of any life worth living. They have to be taught that.”

Simply put but so true!

I’m so glad I read this. Very well written! 10/10, would read again.

Seriously though, thanks. I’m loving the trans* content on Autostraddle lately; it’s been so helpful and eyeopening to (cis, white, priveleged) me. Not only did I learn a lot about FFS, which I had never even heard of before (and yes, I am also struggling with not reading it as for fuck’s sake), but this also challenged some preconceived notions I didn’t realize I’d picked up about transitioning and the many ways in can look.

Thanks for sharing your story, Olivia!

Hey Olivia I would LOVE to chat with you about all the fun and joy of FFS sometime. I have gone through this as well. The shift and the sudden (well, after the swelling goes down) difference can be so incredible. And I still put my chin on my hands sometimes for support when in class and I am surprised at the difference in the subtle shape of things. Been nearly a year for me.

I even posted an immediately after video blog of myself looking like a Mrs. Potato head, drain and all, babbling about the process. It will remain as a testament to why you shouldn’t vlog when on a lot of painkillers :)

(Which I was definitely on despite claiming I wasn’t, I am vague on the details).

hahahaha yes the drainnnn. “yeah I’ll just carry this around, sure. great.”

You look beautiful – thanks for sharing your story! I’m sorry you’re having to fight your insurance company, that is never pleasent. I didn’t realize there were any plans that covered FFS, so that is good news – even if actually getting reimbursed is proving difficult. I hope you win the battle! I’m happy that more plans are starting to cover trans* related surgeries, even if it’s still pathetically few. It’s frustrating to see friends denied medically necessary procedures because they are classified as “cosmetic.”

CA law forbids exclusion and limitation of transgender medical care. If you live in that state and have health insurance, you are legally entitled to have FFS and anything else in the WPATH SOC covered. No matter what your stupid fucking policy says.I believe a couple other states are now like this, not sure.

The bad news is that health insurance is necessarily a monstrous criminal enterprise. I hope to publish a follow-up article about how I won my own fight against Anthem, but that… might take a while, lol. I’m happy to help with what I know about insurance law if you have any questions.

Hopefully other states will follow, especially my home state of NY. Glad you prevailed against your insurance company! That can be a challenge, even when the law is on your side. And I would love to read that follow-up article – the insurance industry is so crazy in this country. I know lots of people who have had trouble being reimbursed even for simple things that are clearly covered.

Sadly, telling the story of “how I won my own fight against Anthem” was meant as a purely aspirational statement – I haven’t curb-stomped those miserable bastards yet. But I genuinely think it’s going to happen. If I’m really lucky I’ll prevent them from just paying me and then pretending it never happened and going back to business as usual. I suppose we’ll see…

Oh no, I misinterpreted your statement – Good luck!! I feel like insurance companies count on people just getting frustrated or confused and giving up – if you keep at it I’m sure you will win. It’s ridiculous that they are making you jump through hoops like this though. I hope we get some genuine reform soon. The Affordable Care Act has instituted some positive changes, but it’s basically a band-aid.

> CA law forbids exclusion and limitation of transgender

> medical care. If you live in that state and have health

> insurance, you are legally entitled to have FFS and

> anything else in the WPATH SOC covered.

While CA Health & Safety code section 1365.5 et. al. (the Insurance Gender Non-discrimination Act) does prohibit insurance discrimination based on gender identity and the California DMHC (Department of Managed Health Care) recently issued a guidance letter to health insurance companies reminding them of their obligations to that effect, (a mere 6 years later…) I think it may be premature to say with certainty that all plans are currently required under state law to cover FFS.

Cases like yours may decide this and it may depend on specific language and coverage in the plan. Plans are allowed to have what is called “non-discriminatory exclusions” which could impact trans health care in some cases, though it’s unclear how this interacts with the criteria for “medically necessary”. It is also unclear whether DMHC’s guidance will result in new less obviously discriminatory exclusions popping up immediately after removal of the illegal ones. It is sticky and I’m not sure it’s safe to say it’s a done deal yet.

Just thought I’d mention that so others reading are aware that it’s still an area where coverage has the possibility to be more unreliable than we might hope and it might be a good idea to be careful.

Obvs, I look forward to hearing how things go and am rooting for you. I think often in the past, persistence has been a notable factor in whether an individual trans person gets something covered. But in any case, it would be particularly notable if you ended up pursuing DMHC’s IMR process and ended up getting good results with it.

Note: If it isn’t obvious, I’m not a lawyer, I just occasionally read California state codes for fun and track trans-related laws in our state closely. So who knows. I just wish there was a lot more clarity around this subject than there is and it was cut and dry.

You’re quite correct, I’m not aware of any precedent here and how this goes for me might determine a lot. My impression is that as usual, it comes down to whether anyone’s willing to listen to us honestly or not. My EOB says that cosmetic exclusions do not apply to transgender surgery under my plan, Anthem’s representatives repeatedly told me that my surgery would be covered, and Anthem’s internal documents reference WPATH SOC V7 as the evidentiary basis for medically necessary gender reassignment before slipping in a little “psst psst ps the following services are not medically necessary because we say so:”

So I think for me, the evidence of discrimination is more or less ironclad. Citing a set of standards of care and only covering the prescribed services you feel like covering is the very definition of arbitrary limitation of coverage. And I’m trying not to get too cocky, but I don’t see how this could not set exact the precedent I hope for in terms of what other patients are understood to be entitled to. The rationale for coverage of SRS and HRT is exactly the same – these services treat gender dysphoria, a serious medical condition.

Having been raised by two lawyers, I grew up with the understanding that if I have to be in this kind of dispute, I have in a very real sense already lost. And that’s true, it’s fucking wretched to have to contort yourself around the Reasonable Person’s idea of how one documents and demonstrates oppression. What happens will basically hang on “is someone willing to take this fraud seriously or not” and not any objective, True legal empiricism. I have no idea what will happen here, but I’m keeping my hopes up :-)

I was already loving this (even if I had to skip the surgery details because thinking about blood, tubes, cuts, etc. makes me queasy and light-headed), but then you referenced Archer and you might be my favorite. Just FYI.

This was such a great piece, in a multitude of ways! You are a beautiful writer and a beautiful woman. <3

This is so well-written! Great article.

Omigod, this was the coolest fucking article ever. Your radiographs are so cool omigod omigod omigod #osteologygeekout (This is so appropriate that I’m in the bone lab right now as I read and write this)

Also, you remind me of Katharine McPhee which is bomb.

I’m amazed at your strength going through this! I think about getting FFS done in the distant future and my head starts to hurt and I get tired.

I found that so much of your piece resonates with me. Especially the parts about holding yourself hostage in the mirror (I am late for EVERYTHING without fail, and this is most of the reason) and always worrying about your face in public. I’m constantly freaking out about how my hair falls over it and such, trying to keep from wearing things with high necklines to keep attention off my heavy lower jaw.

I also worry about the surgery itself. I want my face to still be “mine,” just a female version. It’s obviously more complicated than that in practice, but it’s important to me to preserve “family resemblance” (even though I hate my family). I have two friends who went through FFS, one all at once and the other in stages with different surgeons. This isn’t nearly enough to make a decision on a surgeon. I have a long time to decide, since I’m a law student and I’m more than broke right now (and likely to be for the next decade or so), but I don’t know how I’ll do it even when/if I could afford to.

I still think about that – which of all the possible outcomes would I accept as “myself”? How specific were my needs, really? What I needed was to be able to recognize myself “as female” – if I needed it badly enough to get surgery, was limiting myself to something subtle a dangerous act of vanity? I liked a lot about how I looked, it just also caused me pain. It’s hard to think that any radical difference would disappoint me if I still felt the same basic freedom I do now, but I really can’t say. I went into this knowing at least one person who’d had extensive FFS and looked wonderful and still couldn’t see it in herself, which was very sobering. Really, what I knew is that if I didn’t try something like this, it definitely wouldn’t improve.

I think the good news is that it actually is a misconception that plastic surgery can easily make someone look “totally different,” although of course how people evaluate things like that is going to be bitterly subjective. I will never know how accurate my observations about this process really are, in a way – things have turned out very well for me, but I can’t say how likely that was to have happened, only that it did. I think it’s a call people can only really make for themselves, you know? I hope that whatever you end up doing, you get exactly what you need.

It’s a vortex of unanswerable questions, for sure. Congrats and thanks so much for writing this!

You are so fantastic. I absolutely loved reading this essay. :)

Thanks Olivia, this piece of writing is well done. The more I read this series, the more I find myself really happy about some of the amazing writing that has shown up. Not only is Autostraddle covering new ground, most of the writing involved is spectacular.

Ugh, I identify SO HARD with your thought processes during the research and decision process and before that. I transitioned 5 years ago (holy shit) and still think about getting FFS. For all the reasons. Argh.

Would love to hear more as you heal :)

Holy shit. This is amazing. Love your style of writing and am pretty much blown away by how cool it is that something like FFS exists. Good on ya mate!

We have the same hair because the universe loves us.

Thank you for this article. I have had several friends talk to me about FFS in the past, and I’ll admit to having a great deal of concern. I recognize now I just need to STFU and be supportive.

I had jaw realignment surgery as a teen to correct a really bad open bite, and had to get a titanium plate similar to yours, and it sucked. It took over a year to heal and several more to get use to metal plates in my face. Any time someone would bring up FFS, I could only think about how much it physically hurt. But that is such a small part of the whole process and I need to remember that.

So instead I will give you this small bit of advise: the metal plate in your chin will get cold when the temperature drops or there is a lot of wind. Having the inside of your face get cold is weird, so I recommend starting a scarf collection if you don’t have one already.

So far, I haven’t noticed anything, but thank you. I think they just used pins in my case, and I may even be able to feel them under my jaw, unless I’ve gotten *really* lucky and that’s the button that releases a swarm of attack nanites…

this was beautifully written– thank you for sharing your story! (and your cheekbones are INCREDIBLE, by the by!)

IMO you were stunningly beautiful before and are stunningly beautiful now. I know a little bit about plastic surgery, having had some procedures myself and your choices are yours and should be respected.

You are a total babe and I can see you would have an amazing career as a fashion model (but don’t, that industry is crazy).

Thank you for sharing your story.

I’m scared I’m breaking some rules or something by asking this. This was a great article. I stumbled on it because even though I did some searches a while back, now I’m seriously looking for an FFS surgeon to schedule a consultation with. It sounds like you definitely recommend going to several to figure out who suits you, but for what it’s worth, the attitude of the one you found sounds exactly like that kind of person I would like to start with :) If you can’t let me know somehow who it was, could you at least give me some advice for tracking down where to start? Consultations are expensive =/ And maybe its different from when I looked in to this a couple years ago, but… the lawyer at the TG law center, at least back then, told me that, as of then, no FFS surgeries had ever been covered and paid towards by any insurance companies. Not sure if it was his client, but he mentioned someone who had just many tends of thousands of dollars trying to take an insurance company to court, and unfortunately lost. I’m hoping things have changed in the last couple years, and I sincerely hope you win your fight.

Hey there! I’m glad you liked the article, and you’re absolutely not breaking any rules by asking for specifics. It seemed “maybe not a good idea, as a gut feeling” to name names, etc. in the public article, but I’d be thrilled if there’s any way I can help you. I’ll send you a PM with my email address, please just bump this comment thread if you don’t get that and we’ll find some other way.

I can certainly tell you who I worked with, and will add that I didn’t pay for a single consultation – of course, for a lot of complicated reasons I was also comfortable making more decisions earlier, without necessarily meeting every surgeon I talked to in person. If you like, I can tell you more about my own process. It might help you winnow a large number of options down to just one or two you’d like to consult with face-to-face.

Things are a bit better than they were even, idk, 5 years ago – I’m fairly certain some FFS coverage has been successfully used, in the “in the history of ever” sense. But it is absolutely new legal ground and I have no idea how my case is going to go. I’m hoping to mail the documents out this week – all 65+ pages across 4 CCs, christ – so I guess we’ll see! Thanks again for your support and kind words.

hmm, doesn’t look like I can PM you – oh well! Please shoot me an email; collaterly A T gmail D O T com

Would you mind if I contact you about your selection process, as well? Even though I can’t afford it in the foreseeable future, I still want FFS and just moping about my nasty man-face is worse than spending some time actually figuring out what surgeon(s) I want to go with. The problem is, I have no idea how to go about deciding on a therapist.

I wouldn’t mind a bit – please do!

i accidentally a word or three.

Olivia, in years of reading,this is, without a doubt, the most amazing and informative piece i have ever read about ffs. though not in the market myself (absolutely nuthin’ could help this ol’ dilapidated face, though i am considering a little nip/tuck action), it’s a subject that comes up a lot in conversations with my younger sisters. I’ll be passing this along and linking it a few times so it can spread around.

your joy is palpable and i congratulate you on your fortitude, not only in the face of the pain of the procedures and recovery, but especially in your strength of conviction in the face of the many naysayers expected and unexpected.

additionally, the lengthy comments section (yes, i read it all)is a worthwhile experience in openness and self-assuredness.

(deep thanks to autostraddle, too, for welcoming #girlslikeus and giving us space…)

Gurll u are so truly btfull.Keep up the good pleasant face.dee

It’s amazing what a Rorschach Test your article is, bringing out a lot of issues that it throws back for people. Thanks for taking the trouble to track, document, and report on your experience to all of us.

I couldn’t possibly classify what kind of transperson I am, but I like very much your defense of all of us, whatever position we are in.

I think it’s great that you finally have a face that feels like the you inside, and I admire your bravery and persistence in getting it done. Much sucess in the future.

Moron is an ableist slur that has been used to justify systemic violence and oppression of autistics and developmentally and intellectually disabled people, and it really hurt me to be punched in the gut with it out of nowhere here. Please stop scapegoating disabled people for the actions and attitudes of evil, malicious, callous, arrogant people who have a vested interest in ignorance. you’re killing me. and please don’t gaslight me, i can’t take another gaslighting from a self-anointed activist space this week. just please take my word for it that I’m super totally a person and have feelings and there isn’t some evil/funny/nonhuman/disposable part of me which was separarely abused for being disabled vs the important/heroic/salvageable/human part of me that was abused for being trans*. I’m really disappointed and tired and sick of being hurt by people who claim me as part of their community.

I was doing some research for transop.com and I stumbled upon your essay. I imagine that many others have enjoyed it and found it inspirational as they consider or plan facial feminization surgery. Your cheeks are so stunning that I had to read the essay again just to make sure that you didn’t have cheek implants placed. Kudos for the perfect natural cheekbones! Your results were great, too. But, it’s too bad that the doc didn’t let you have some of the bone from your chin. Those would have made some killer earrings!

Thank you for sharing. I go in for my own ffs July 1st. just 2 short months away. I am by turns elated and terrified. I can hardly wait and I want to run away and hide.

Its good though. A new chapter in an old book. A 2nd chance at life in a world that grants very few. I hope I can manage my own as well as it seems you have.

Not only reconstructive surgery is helping people that has similar problems, medical improvements like facial feminization surgery is giving a lot of people a chance of being what they would like to be, despite of the fact that anyone should love herself like you do.

Regards.

http://facialteam.eu

as a non-transitioning male to female, I absolutely loved your story. I think you are absolutely beautiful, feminine, articulate and brave. Having been called names, threatened, fired from my job, because of who I am, Not what I did, I am so very proud of you as a woman and a sister.