all photos by Kade Alpers Photography

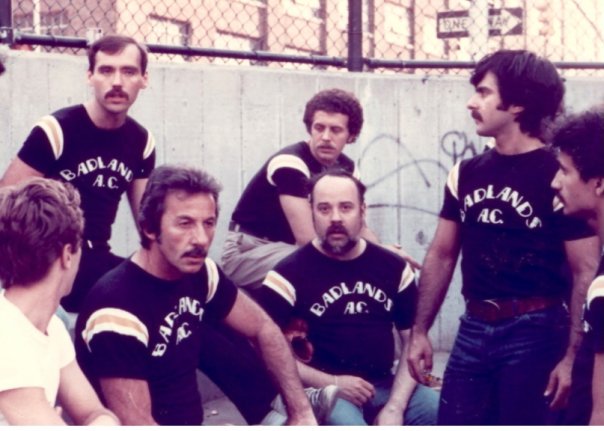

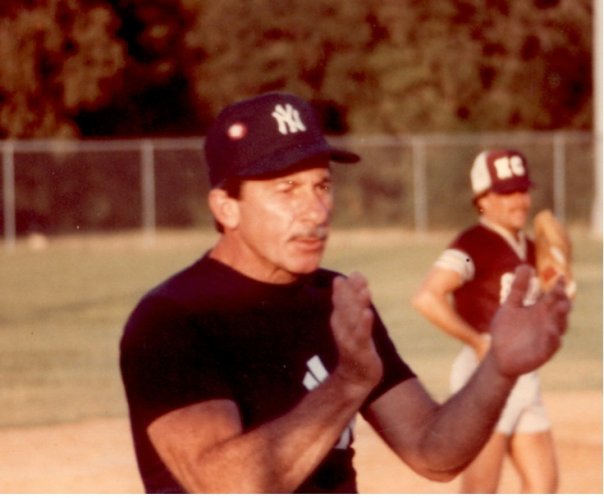

In 1976, Chuck Dima, now considered “grandfather of gay softball”, teamed up with friends to form a new LGBTQ sports league, Big Apple Softball. Dima noticed a desire for a queer social space outside of a drinking environment after often being asked to play softball with a group of gay friends. He owned the Badlands bar on Christopher Street so he spread the word to the greater gay community by advertising in the bar as well as putting up fliers on lampposts. Dima and his crew were able to assemble 12 teams and about 140 players to compete in the league’s first season in 1977, all sponsored and supported by various NYC gay bars. This summer BASL is still going strong, entering its 48th season with 36 teams and over 700 players.

BASL was originally primarily comprised of gay men, but over the years, more women and queer people joined the league. In 2009, the official Women’s Division was introduced. In 2013, the name was changed to the W+ Conference, which is open to “cis-women, trans men and women, and non-binary folks,” according to their bylaws. As of this year, the conference is changing its name once more to be more explicitly inclusive, becoming the WTNB (women, trans, and non-binary) Division.

The current league has two conferences: the Open Conference and the aforementioned WTNB Conference. Within the conferences, BASL offers different subdivisions for players to join, determined by skill level. There are competitive teams for lifelong softball players and more recreational teams for casual players. This allows for anyone to participate in the league, regardless of softball experience. Between commissioners, the executive committee, the committee chairs, and the team managers, 93 people work together to pull off one season. “There’s a whole village and it takes that village to run this softball league,” Andy Gandy, the current league commissioner, tells me. Gandy oversees both the Open and WTNB Conferences.

“Sports historically are… their own community and their own communal space,” says Danielle Regina, the assistant commissioner leading the WTNB Conference. “I’ve played softball my entire life, I played Division 1 softball in college. In all my years playing, this is the first time I have felt truly at ease in my own game because I’m with people who look like me, who talk like me, who understand the world that I’m in.”

“When people step on my fields, they may have never played sports before, they may have never played softball before, but they’re getting experiences now that their younger self perhaps did not have the opportunity to have,” Regina adds. “That’s what we’re really doing here, is we’re pulling out everybody’s inner child and saying you are allowed to be here, you are allowed to play here, and it doesn’t matter if you’re any good…we just want you to be here in this space with us.”

Gandy adds that he didn’t participate in sports in high school due to the hypermasculinity enforced in those spaces. He says the founders wanted to create a league where those specific gender roles and rules were removed. “Then you would have a group of people who would be able to play softball and feel safe,” Gandy says.

That ethos of inclusion and connecting with one’s inner child is especially significant for queer people. As Regina explains, BASL is built on the knowledge that for queer people, physical safety can’t always be guaranteed in spaces. “And now you’re talking about athletics, which is an incredibly intimidating, physically intimidating, environment,” Regina says. “To have a space that is completely your own, that you can show up as you are — if you want to show up in drag, if you want to show up and show off your scars, nobody is going to say anything outside of celebrating you — I think that’s very powerful.” Queer people deserve more spaces in which to physically express themselves.

The context in which Dima and his friends created BASL wasn’t all that different from the context in which BASL operates today. “The mission of Big Apple Softball League then was to find a safe space for — at that time we were all lumped under the word gay — so it was to find a safe space for the gay community outside of the bars to play softball,” Gandy says. In 47 years, that mission hasn’t changed. This was one of the first organizations in the country to provide a space for LGBTQ people to play softball. Dima is considered a pioneer in the world of gay sports. The highest skill level division in BASL’s open conference is named “Dima.” And not only does his legacy live on, but so does the need for inclusive athletic spaces that also function as LGBTQ community hubs.

What started as a humble 12-team league has grown through the years. In The Advocate’s Sportside section in 1981, Neil Russo wrote: “[1980] was a banner year for Gay Sports…The Big Apple Softball League grew to 16 teams…The most important fact about Gay Sports is that it is here. It is available for all gay men and gay women to be a part of. It is a way to have fun and meet people at the same time. I have bowled and played ball all my life, but I have never enjoyed myself as much as I am not with my brothers and sisters. All the sports are for both those who are proficient and for those who want to learn.”

Longtime BASL athlete John Panarce says the organization started with just two softball fields, one in the middle of West Village. “It was a very small softball field to the point where we would break a lot of windows,” Panarce says. He has been involved with BASL since 1980 and has a division in the open conference named after him.

Panarce credits player Stan Witt with helping BASL grow from those two small fields to the many Randall’s Island fields it now plays on. Witt played on a team in BASL until he was 87. The more players I speak with, the more stories like this I hear; for many, BASL is a lifelong commitment and community.

After being founded in the late 70s, the team grew quickly. The mentality was, “Get as many people as possible involved,” Panarce says. “If you are good at running parties, boom, you became the party chairman…One of the guys on my team was a lawyer. Well, that’s how we got incorporated. It’s basically looking for people who can do the things. An accountant, guess what? Treasurer.”

In the 80s and 90s, the team continued to provide a community for LGBTQ New Yorkers during the AIDS crisis. “They rallied a bunch of people to help contribute in that regard,” Regina says.“They’ve offered resources to other leagues. In that 1970 to 1990 range, a lot of their political contribution and communal contributions surrounded the AIDS epidemic and helping their team members.”

“That was a horrible, horrible time… I don’t wanna tell you the number of memorials I went to. We lost almost half the league. But, we were very supportive of… people who have AIDS still playing softball in the league,” Panarce adds.

The league remains involved in political issues facing queer people to this day. “A lot of us now protest consistently to this day the same things that they did in the 70s,” Regina says. “We’re doing the dyke march, we’re doing all of the other marches that are available throughout the year that we’ve participated in every year since the 70s. We’re working with youth now, with the Ali Forney Center, to get kids on softball fields with us so that we can let them know that these spaces exist.”

The league’s advocacy work is indeed focused on getting the next generation of queer youth on the field. “How do we give them gloves? How do we set them up with some of our players as mentors?” Regina adds. The league is also committed to working with organizations to fight trans bans in sports, especially the Nassau County ban on trans women and girls from participating in women’s sports at facilities run by the county.

WTNB hosts visibility days at their games, focusing each day on a different identity. They fly Pride flags alongside educational placards at the games, highlighting the history and significance of each letter in the LGBTQIA acronym. “There’s a lot of things that queer people don’t know about their queer siblings until they learn about it,” says Regina. Heading into this next year, WTNB will be looking to specifically grow ways to support trans and nonbinary players.

WTNB has already begun partnering with other queer organizations for these goals. They’re working with organizations that sell or donate products for athletic trans care, including athletic tape specifically for gender-affirming surgery scars. “Those types of partnerships are really cool, and the visibility [days] are really cool because they let our players know that we’re listening, we see them, and that their space is valuable within our organization,” says Regina. “And they see themselves in our sponsorships. They see themselves on our field.”

Modern-day BASL is only growing. “This group of people became that adoptive family that we talk about so much within our community,” Gandy says. “The league is a very social league. Most people are joining in to meet other people within the community, and it’s amazing. I know so many people that not only have their adoptive family, but they’ve met their husband, wife, significant others through the league.” Gandy adds that, sure, the league has technically grown in literal numbers, but what’s more significant is how it has grown in the strength of its community. “It does empower you not just within softball, but in your regular life,” he says.

In late July, I headed up to Randall’s Island to watch the Big Apple Softball League season playoffs. Randall’s Island is connected to Manhattan but feels like its own little world: green field after green field with bright blue shores.

For the playoffs, the teams fly all of the Pride flags on each field, the culmination of a season of Visibility days. As the players go from game to game, they play in front of all the different Pride colors waving in the air.

The WTNB league’s 16 teams played simultaneous matches on the many fields to determine the champion teams. Within the league, there are three subdivisions, determined by player expertise. The divisions are named after players who have significantly contributed to BASL over the years, such as the Green-Batten division, named after longtime players and leaders Cynthia Green and Scott Batten.

Cynthia Green is credited with creating the Women’s Division alongside Batten back in 2009. She now umpires for the league.

I spoke with her in between one of the many games she umpired. “I’ve been very involved. I have a lot of friends here. I love the league because… it’s very welcoming, you know, to everyone, and we have a lot of fun, so when I come back here to umpire I always look forward to it,” Green says, adding that it’s important that people can play without the fear of judgment or discomfort. “This is one of the reasons why I feel happy and proud being a part of the league. All the people that have been here, they’ve played for many, many years. I just love where everybody knows everyone… You know, I see my friends that I know from way back when.”

As I spoke with more players, practically everyone mentioned Green and her positive impact on the league, specifically her efforts to recruit players and create the now thriving WTNB league.

The WTNB balances connections to the past with a younger, modern perspective on sports and queer life. The league has Gen Z presence, which is clear throughout the playoffs. Multiple teams celebrated their victories by dancing to “Hot To Go” by Chappell Roan, and one team spent their downtime filming themselves doing the Charli XCX “Apple” dance.

Even as it moves into the future, the connection to the league’s history is apparent; many of the teams are still sponsored by gay bars in New York, such as Cubbyhole, Henrietta’s, ICON, and Kween.

“It’s great because we patron [gay bars] after the games typically,” says Zinny, a player on the team Hellcats. “It’s good to keep the money in the community, it keeps safe spaces open for us to go to outside of the games.”

Since the conference was founded in 2009, the WTNB League continues to evolve. Enthusiasm for this iteration of the league is only growing. Over the last two years, membership has “practically doubled,” Berman tells me. Moving on from the title of Women’s to the W+ to the WTNB Conference reflects an explicit desire to create a space for trans and nonbinary players.

“We’ve taken this conference and we’ve turned it into an actual family, people who care for each other and want to feel safe around each other,” Regina says. “Cisgender men, whether they are gay or they are straight, have been given the opportunity to take up space without question since the beginning of time, literally since Eve ate the apple… But we have to fight for our space. We have to carve it out. We have to make those spaces. You need to go out and create a space that says, this is just for you. It’s built for you.”

“For me, I will never go back to playing traditional softball again,” Regina says.

Hutch Shea Hutchinson, the manager of Team Stix, has been playing in BASL for the last decade. Hutch has seen the league become more trans-inclusive over that time. “I was the only trans masculine person in the league for a very long time,” Hutch says. When Hutch first came out as trans, the league followed NCAA standards, which maintained testosterone was a doping drug. “I take testosterone to save my own life, not to be better at recreational softball,” Hutch says. “I think that the league has come leaps and bounds from where it was. Now there’s trans masc people on every team.”

The open division of BASL allows players of any identity. Some women and trans players do play in the open division currently. But others, like Hutch, prefer the WTNB division. “I did try playing in the open division once. And I think that socially and politically, like, as a queer person, my values and the style of softball that I play is rooted in women’s sports historically,” Hutch says. “I’ve been here since before I identified as trans, so I’ve kind of come out in this league. And I will say that this iteration of the league is the most inclusive. It’s the most expansive that we’ve ever been.”

In addition to players, there is a strong community of WTNB supporters. Kelly Bodrato attends games regularly to cheer on her daughter Chelsea, who plays on Venom. “When she was little, I went to all her games, so now I’m here, cheering her on again!”

Many of the longtime players are mentors to the younger generation and are clearly beloved. As I spoke with Nancy Killian, who has played in BASL for 18 years and is in her seventies, her teammates from Stix chimed in with praise. Stix is one of the teams in the most competitive division, and Killian is an active member.

“She’s in the BASL Hall of Fame, you know,” Hutch informs me proudly.

The Big Apple Softball League Hall of Fame is the highest honor a BASL member can receive and is reserved for members who have been involved for over 10 seasons and have made “significant contributions to the league.”

Nancy Killian started playing in BASL in 2006 and has played in the WTNB league since it was founded. “I started on a team called Last Licks, which I just think is, like, the best name for a gay softball team! And then I joined a team called Chicks with Stix. And now we’re called Stix to reflect our changing demographic. And it’s just been an awesome, awesome time.”

Killian made it to the finals of the Amateur Sports Alliance of North America (ASANA) Softball World Series with the BASL team Lavender Menace. She was voted MVP by her teammates last year. “I played in the World Series the past couple of years, and I think it’s awesome. And the kids all get a kick out of me, you know, merely because I’m old, and I just love it. And they’re always asking me, if I’m on the field, like, do you need water? Is it too hot? And I’m like, I’m fine. You know?” Killian says, laughing fondly. “And they’re really nice to my wife.”

Killian has been involved with LGBTQ softball leagues since the 90s and spoke to me about the importance of queer spaces in sports: “I played with a person who was totally in the closet. She knew that I was out and she knew me and my wife… I think we really helped her, to become more comfortable in coming out… a few years later, she called me up and said, do you wanna play with us on Last Licks? I thought it was a nice full-circle type of thing… I think that if my friend had found BASL a little earlier in the 90s, you know, it would have really helped her coming out journey. I was actually in a gay league in the early 90s called Women Athletes of New York, which has folded since. That was where I first saw people that I wanted to identify with and people that I felt comfortable being like. And it was very, very important to have that.”

Brenda Berman is another longtime player; she has been in BASL for 20 years and manages the Green-Batten division team Venom.

“This has been the best thing that I have in my life, that I’ve done, for 20 years,” Berman says. “And I’ve managed this team for 13 years, this is our 13th season. And we were first place in the season last year, and we’re hoping to take the championship this year.”

Venom did indeed take the championship in the Green-Batten division this season.

Berman spoke with me emphatically about the value of spaces for women, trans, and nonbinary people in sports. “When you’re looking for some place and you’re like us… To find a place where we’re all-inclusive… is so important for everybody, especially for youngsters. We have a lot of people in BASL that help guide and mentor youngsters… It’s not just about, let’s go play ball, and then we all run home,” Berman says. “We do a lot of extracurricular activities. We do a lot of fundraising. We’re having a picnic after today’s games… Opening day for W+ was awesome, we had a marching band! I mean, we really go all out, and it’s all-inclusive, and we make everybody feel welcome and comfortable.”

Ginny Lentino manages the Brewers team, which also plays in the most competitive division. Lentino has been involved with BASL for 33 years. She recalls how when she started with the league there weren’t really any women but how folks like Scott Batten and Cynthia Green put a lot of work into recruiting more women for the league.

Lentino was awarded the Carey the Torch Award by the W.P Carey Foundation for her positive impact on the Big Apple Softball League. BASL leadership writes of Lentino: “Ginny’s rookie season was over thirty years ago when one of the only safe places for our people to express themselves openly was in a gay bar. Over the past three decades, Ginny has generously volunteered her time and energy in leadership roles to give back to her beloved softball league and the greater LGBTQ community. Her efforts have enabled countless individuals to participate in not only an athletic space but a queer community that fosters inclusion, diversity, safety, and family.”

Lentino was the first woman inducted into the BASL Hall of Fame and remains a significant presence in the community.

“There are a lot of people who don’t have the support and backing from their families, but they know they can come here no matter what. We may argue on the field but everybody has each other’s backs,” Lentino says.

Indeed, throughout the day, I witnessed heated arguments over referee calls and coaching decisions. Later, I saw those same players laughing together and checking in on each other in the midday heat.

The teams are tight-knit within the league. Lentino speaks fondly of the Brewers: “This is my second family… On and off the field, I love this team so much, they’re amazing people.”

In just an afternoon at Randall’s Island, I met many mentors and leaders in the New York LGBTQ community. The good sportsmanship, community, and leadership I witnessed demonstrated the value of queer spaces in sports.

When I asked Assistant Commissioner of WTNB Danielle Regina what the future holds for the league, they had plenty of plans: adding vision-impaired accessibility to the fields, campaigning against anti-trans legislation, and queering softball overall.

“I think that we’re gonna become more part of the conversation that says softball needs to be queer. It’s not currently queer,” Regina says. “The softball world is built around hair bows and a very effeminate presentation of people. It’s not yet queer. So my goal is that our organization sets the tone for what that inclusive environment could look like on a softball field. Like, you look at a professional roster or college roster, you’re not gonna see androgynous people or people with different colored hair or people with scars. You’re not gonna see that. But on our fields, you’re gonna see a spectrum of shapes, sizes, colors, and abilities, and that is what softball needs.”

But most importantly, Regina says, the future is “more queer people and more softball.”

Comments

This was an incredible article! I love this sort of deep dive – and it’s inspired me to get back into softball when the season comes round again!

Katie – Danielle here from the WTNB Conference! Let me be the first to say, come on over!

💌: Asstcommishwomen@bigapplesoftball.com – shoot me an email if you’d like to give it a go!

That’s so sweet! In an ideal world I would love to, but unfortunately I live on the wrong side of the Atlantic – Oxford UK just has enough expats we have a league here! Not specifically queer, alas.

I love EVERYTHING about this article and this league. Celebrating queer joy and sports – doesn’t get any better.