A new book on Gandhi by Joseph Lelyveld may be banned in India before it’s even published. It’s already been banned in Gujarat, the state Gandhi grew up in. This is problematic, but then, so are the suggestions that the book suggests that Gandhi might have been bisexual and that this is a. relevant and b. a bad thing. Let’s discuss.

Lelyveld’s Great Soul: Mahatma Gandhi and His Struggle With India draws on historical letters and other research as a means of exploring Gandhi’s life, his struggle for social justice, and the evolution of his values. It is currently available in print in the U.S. and as an e-book but has not yet been published in India. However, on the basis of several reviews, it’s launching debate anyway.

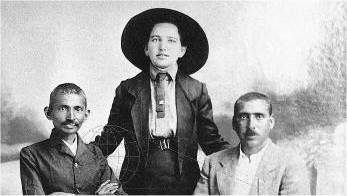

In what seems like an intentionally inflammatory review in the Wall Street Journal, Andrew Roberts argues that this particular depiction “gives readers more than enough information to discern that he was a sexual weirdo, a political incompetent and a fanatical faddist—one who was often downright cruel to those around him.” He also argues that Gandhi was a hypocrite, because he denounced lawyers but was one; quotes from people who called him “devious and untrustworthy”; and mentions his hemorrhoids. In a section of the review that seems to be causing a large amount of controversy, he also writes that Gandhi was in love with with Hermann Kallenbach, an architect and bodybuilder Gandhi lived with in Johannesburg, South Africa. Roberts speculates on alternative uses for the cotton wool and Vaseline that Gandhi’s letters say remind him of Kallenbach (Lelyveld relates these to the enemas Gandhi gave himself) and suggests that when Gandhi asked Kallenbach to “promise not to ‘look lustfully upon any woman” he meant himself as an alternative.

The review ends with a statement of Roberts’ belief that Gandhi’s campaigns were ineffective, and the only one that worked — getting the British out of India — was only successful because they were leaving anyway. To Indians who regard Gandhi as a father to the nation and his philosophies as part of the foundation of the country, this is deeply shocking and offensive. Other reviews, such as those in the Daily Mail and the Mumbai Mirror cite the same passages that Roberts does, in one case under the headline, “Book claims German man was Gandhi’s secret love.”

The book, which has not been published in India yet, is being considered for a ban on the sole basis of reviews like the one in the Wall Street Journal (Roberts, who is a British historian, also has a book coming out in May, and is probably getting a ton of residual publicity from his review). This is before anyone in India has actually read it.

In an interview with the New York Times, Lelyveld, who has previously won a Pulitzer, emphasizes that he “treaded very carefully” with the book and says “I’m surprised to find myself at the center of [a spectacle], because I think this is a careful book, and I consider myself a friend of India.” Additionally, in an email to the Associated Press, he writes, “The book does not say that Gandhi was bisexual or homosexual. It says that he was celibate and deeply attached to Kallenbach. This is not news.” He also says he hopes someone will read it before it gets banned.

But right now, on the basis of the reviews alone, things aren’t looking good. Narendra Modi, chief minister of Gujarat, said the book was “perverse in nature” and that it “has hurt the sentiments of those with capacity for sane and logical thinking.” M. Veerappa Moily, India’s law minister, said “the book denigrates the national pride and leadership” and that officials will consider banning it. While it’s possible for anyone to suggest that a book be banned, less than one a year actually is.

According to the New York Times, the central issues at play are the public perceptions of both sexuality and Gandhi. While India has recently become less sexually conservative, coming out as anything but straight is still a big deal, and a law against sodomy was only struck down in 2009. Additionally, despite Gandhi’s status and influence, like any public/historical figure, there is a wide range of knowledge about his life and philosophy, and a lot of it is idyllic.

Finally, and perhaps most relevant to your interests, there is the issue of whether or not Gandhi was gay. Roberts snidely suggests that he was. Andrew Sullivan, in the Atlantic, suggests that “based on this evidence” he must have been. Lelyveld says his book does not say Gandhi was gay or bisexual. It would be radical in India to sugget that Roberts and Sullivan are right; it would be radical anywhere else to suggest that Lelyveld is, and that two men can care about each other as deeply as Gandhi and Kallenbach seem to have without being in a relationship. Or even more radically: maybe, in light of everything he did, Gandhi’s sex life should not even be an issue.