Over Thanksgiving this year, my younger sister and I caught up with our dearest loved ones: Emily Gilmore and Paris Geller. Yes, we rode that Gilmore Girls: A Year In The Life train all the way through “Fall,” “Spring,” “Summer,” and “Winter.” Returning to Stars Hollow felt like going back to the suburbs where we grew up, where little changes, where certain details will always be true. Rory is still the worst. Paris is still the best. Lauren Graham can still move me to tears by so much as sneezing.

Gilmore Girls: A Year In The Life gives its characters cyclical narratives, insisting that all things will eventually come full circle (there are so many circles in this revival that it’s dizzying). But the most static character is Stars Hollow itself. The town, rumored to have been built within a snow globe, is the same as it ever was, an idyllic bubble so simply composed that its landmarks sound like they’re from a storybook: There’s Gypsy’s autoshop, Luke’s Diner, Miss Patty’s barn-turned-dance-studio, Mrs. Kim’s antique store, Doosey’s Market. Gilmore Girls: A Year In The Life pokes a lot of fun at Stars Hollow’s rigidity, which also has larger implications for the revival’s emotional arc, with Lorelai in particular realizing that a suffocating town can be comforting and familiar, but that doesn’t make it any easier to breathe.

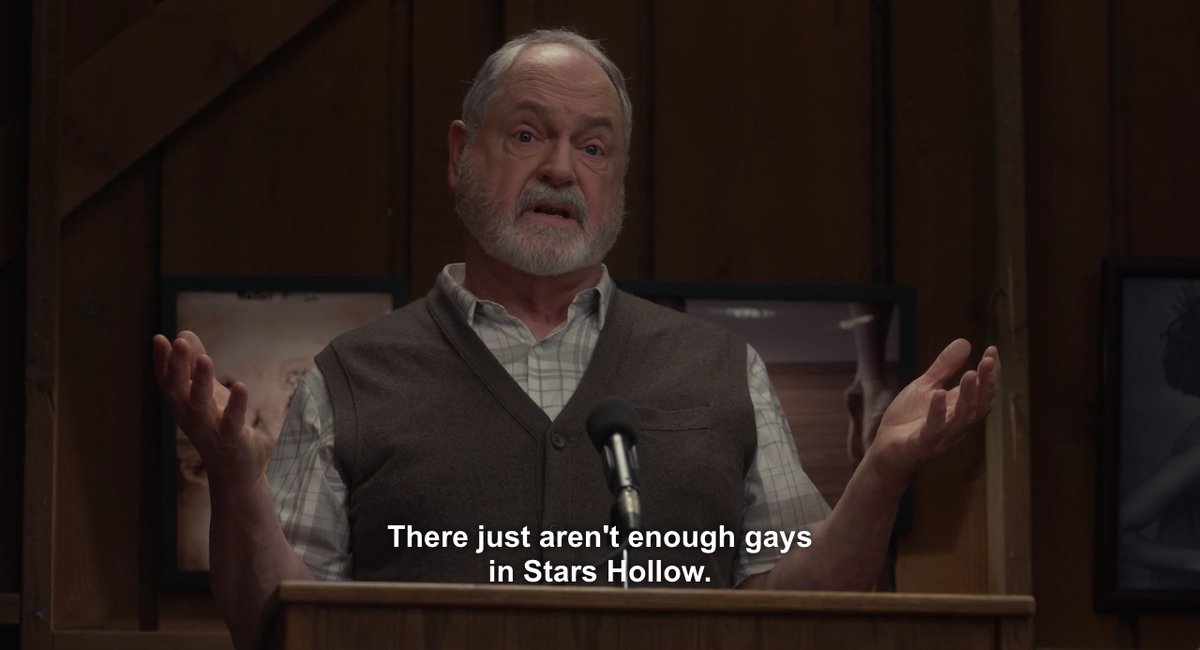

In one of the revival’s town meetings, another antiquated but familiar tradition within the confines of Stars Hollow, the characters become extra self-aware about their town’s shortcomings. Town mayor Taylor Doose informs the residents that Stars Hollow’s pride parade has been cancelled due to a lack of gays. “There just aren’t enough gays in Stars Hollow,” he says, throwing his hands up in disbelief.

I laughed. Of course I laughed. I’ve often complained about the extreme straightness of Gilmore Girls. Look, being a queer woman of color and loving this show leads to a decent amount of cognitive dissonance. A 2016 revival, however, presented an opportunity. The revival could have put an end to the bad racial humor of the original run, but it failed on this front: a nonsensical and offensive runner about Emily and everyone else perplexed over what language her new maid is speaking makes for one of A Year In The Life’s low points. The revival could have injected Gilmore Girls with some queerness, but it failed on this front, too.

Very small strides were made. Even calling them strides seems generous. They were teeny, tiny baby steps. Michel Girard verbally acknowledged having a male partner who he’s thinking of starting a family with. Throughout the series, Michel was coded as gay, but his love life remained undiscussed. While Lorelai rambled on and on and on about her relationships to her annoyed but ultimately patient employees, Michel kept quiet about his own personal life. A Year In The Life cuts the bullshit rather quickly, Michel mentioning his boo Frederick almost as soon as he appears on screen. Then, after Taylor’s town meeting speech, a new character gets introduced: Donald, who serves on the musical committee with Lorelai.

And that’s all. That’s the extent of A Year In The Life’s queer inclusion. One character who we’ve always assumed to be gay says he is indeed gay, and another character we’ve never met comes along but we don’t learn anything else about him other than that he is gay. Why, then, did the writers think it was necessary to include a long and very on-the-nose scene self-reflecting on the show’s lack of queer characters? It may have been good for a quick laugh, but the second the scene ended, I was left feeling perplexed. The show’s meta-commentary may have been funny, but it’s ultimately pointless. The writers acknowledge the problem without actually doing anything about it.

Self-effacing comedy about a lack of diversity is a cop-out move. What does writing a bunch of meta jokes about a lack of gay characters even accomplish? The writers are patting themselves on the back for being aware of their shortcomings but aren’t working on those shortcomings. That’s what I like to call Rory Gilmore-ing: knowing you have a problem but not wanting to do anything to fix it. (Seriously, that’s Rory in a nutshell.) Maybe if this meta scene had taken place in a revival more serious about being inclusive, the joke would have worked. Maybe instead of putting time and energy into a self-reflexive joke about queer representation, the show could have, oh I don’t know, actually written in more queer characters or hired a more diverse staff. It’s self-aware comedy without any self-reflection.

Soon I will go hoarse from shouting this in the streets, but here’s the key to writing queer characters into your television show: YOU JUST DO IT! Okay, so there’s a little more to it than that. You should avoid lazy stereotypes. You should write nuanced and layered queer characters. You should hire queer writers to help write authentic narratives. But I think there’s a tendency for writers to overthink queer inclusion. Here’s the thing though: As with real people in real life, characters on television usually don’t come out as straight. Heterosexuality is assumed. But that means that just because a character hasn’t had a queer storyline before doesn’t mean that it can’t happen later on down the road. How To Get Away With Murder didn’t introduce Annalise Keating’s bisexuality until season two, and it wasn’t in a coming-out story either. It was just new information about the character’s identity and backstory. It was just character development.

I haven’t stopped saying “Paris Geller should have been queer in the revival” since A Year In The Life debuted. I will probably repeat it at least once a week for the rest of my life. It’s partially a joke, but I’m also kind of serious (alright, let’s be real, I’m extremely serious). Mallory Ortberg put the idea in my head that Emily Gilmore should have a late-in-life lesbian storyline, and I couldn’t stop thinking about that while watching the revival either. But when it comes down to it, Gilmore Girls is as heteronormative as it always was.

This isn’t the first time I’ve noticed a show trying to do meta comedy about diversity. The new satirical TBS series Search Party includes a storyline about a white actress cast as a Latina cop on a primetime crime series, underscoring the absurdity of Hollywood’s whitewashing problem. But Search Party itself isn’t exactly a bastion of diversity with its very white depiction of Brooklyn and super white writer’s room. Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt completely doubled-down on its decision to cast a white actress as a Native-American character last season with a baffling meta storyline that did nothing to address the problem other than scream in the faces of its critics. Saturday Night Live makes self-aware jokes about its extreme whiteness almost every week.

Broad City is the only show to come close to pulling self-critiquing comedy like this off. Last season on Broad City, Ilana gradually became more self-aware of her whiteness. At the end of “Rat Pack,” Jaime explicitly tells Ilana she’s guilty of cultural appropriation every time she wears her Latina earrings. The writers point to the problem through Jaime. It’s a smart and sincere scene that has very real character-based implications. Ilana didn’t altogether change overnight, but she listened to Jaime. She reflected. It didn’t seem like the writers were just winking at the audience. Then, there’s a show like Master Of None, which dedicated an entire episode to Hollywood’s lack of roles for Indian actors. But that worked because the critique was outward rather than inward. Master Of None’s critique of South Asian representation in Hollywood came from a show that actively works against the problem by casting Indians in varied and nuanced roles.

But when a very white show makes jokes about whiteness or a very straight show makes jokes about queerness, it’s almost always going to fall flat. Who cares if Gilmore Girls knows it has a problem? Self-awareness doesn’t get you any bonus points. Being aware of the problem enough to the point where you’re pointing and laughing at it isn’t particularly productive or challenging. Meta comedy like this can make me laugh, but it’s often mistaken for something deep and profound. There’s nothing deep about it. Gilmore Girls remains as unbendable as its main characters. It’s familiar, but it’s still so damn suffocating. More television shows should be working to be more inclusive instead of just making jokes about diversity and representation. In the meantime, I’ll be off working on my manifesto on why Paris Geller is a queer icon.

Comments

Thanks for writing this Kayla.

Gilmore Girls has been my favourite show for pretty much my whole life, and anticipating this revival was basically the only thing getting me through 2016. And since watching it I feel so….conflicted. Gilmore Girls has always had its problems, I will be the first to acknowledge that. My biggest concern for the revival was not that things would be different, but that they would be the SAME. That Gilmore Girls in 2016 would have the same problems as Gilmore Girls in 2000-2007. And as you’ve laid out so well, nothing really changed.

I laughed too at the “we need to borrow some gays” line. It was funny, it didn’t really bother me. The things that bothered me was the running “joke” about the family living in Emily’s house, the fat-shaming by the pool in Summer, and the completely offensive transphobic joke said by Finn in Fall. And, well, everything to do with Rory’s entire storyline over all four episodes, but that’s a different article.

Oh my god the fat shaming at the pool! I don’t like Gilmore Girls but my girlfriend does so I’ve been watching these latest episodes with her. I was appalled. They’re boring characters in a poorly written show and I think that could be excused in the original version because it does seem quite dated now but there was no excusing away the fat shaming in the 2016 version.

Yes! And the entire scene was just there to fat-shame people and then move even further to try to evoke some weird sympathy for Rory and Lorelai because it was “just so stressful” for them to be around other humans with bodies enjoying a damn swimming pool.

Ugh that pool scene was so bad and pointless like wtf

Thank you!! I was definitely annoyed by the empty jokes about the lack of queerness, especially with the not-so-subtle hinting that the audience has read Gypsy and Taylor as queer, too.

But the ongoing jokes about Berta and that awful transphobic comment by Finn just angered me to no end! Especially because it went so far beyond “oh we sure lack inclusivity” in the way the meta jokes suggested but were downright offensive and disgusting.

the transphobic comment of finn’s made me actually flinch when i heard it — amy sherman-palladino, what is your problem?

I missed it, probably because I immediately roll my eyes while falling asleep whenever the Life and Death Brigade are around

Sometimes I think they’re only ever around because Alexis Bledel looks kicky in an old fancy hat.

I was so shocked by it that I didn’t think I heard right and had to rewind and unfortunately watch that bit again.

The comment by Finn really floored me. I hated that so much.

Ugh the transphobic comment pissed me off SO MUCH.

That transphobic joke was so so so AWFUL

Alex – I think the joke was:

“Wasn’t that a man?”

“Only for another week?”

It went by so fast but it definitely caught me off guard. How is this okay in 2016?

And also, yes, the fat-shaming pool scene was so unnecessary. Why were they even there?

I don’t recall the unfortunate joke about Finn at all but the fat-shaming was so awlful!

And that Spanic family living with Emily and the jokes about not understanding their language were totally unnecessary, too. I mean, come on, we’re in 2016, in the middle of huge battles about acceptance and visibility in every spectrum of human life, and they pull this kind of crap on us? That was really unnecessary!

I STILL CANNOT BELIEVE THEY REFUSE TO ACKNOWLEDGE THAT PARIS IS QUEER.

Just needed to scream that, sorry. But really.

I would have just settled for more Paris time. She really is the star of the show, in my mind.

Star of the show and all of our hearts.

-Holds out for the world in which Emily and Paris are QUEER TOGETHER-

or i guess that’s what fanfic is for :P

May December terrifying power romance?

I have always watched an unhealthy amount of TV but this is a show that I just couldn’t get into. It was around during my college years and as all my roommates sat around watching in 1 room while I was in the other room watching some other show.

When they announced this revival I was like okay 4 episodes, that I can do and then they mentioned the 4 words at the end, ugh. I don’t mind being spoiled so I found out the 4 words and then I was like, nevermind, that would just give me Skins Fire type rage for it to end like that.

I did wonder though at the very small moment in the community council meeting, when gypsy was like “You can’t think of ANYONE ELSE who might want to be in the parade??” (and in stars hollow, their lesbians have pigtails and wear flannels) and that was a moment when they were like, ah yes, lesbians exist, but we shall not speak of them explicitly.

I know lesbians can have pigtails but they can be pretty infantilizing and they were in this moment, and I think gg costume designer doesn’t know the difference between a tomboy and a full grown lesbian.

(pigtails are political!)

I understood that joke as implying that Taylor was gay, like urging -him- to come out and say what everyone was thinking.

I kinda thought she was referring to Taylor with that quip.

I thought the same about Gypsy! Then a friend pointed out that maybe they were implying Taylor is gay (they all lean in towards him when they ask if he can’t think of any more gays)

BUMMER. I thought he just like, was gay. I also have seen v little GG in my life, just enough to know the characters in broad strokes but not much about say, the boys that Rory has dated or whatever.

I just have Lesbian Vision and see lesbians EVERYWHERE. because they are everywhere. in spite of this heteronormative nonsense.

re: scene with rory and paris in the bathroom I was like AND THEN THEY MAKE OUT. RIGHT. MAKE THIS BE LIKE EVERY GAY MOVIE AND NOW THEY MAKE OUT.

the actress who plays gypsy has said that she played every scene as though she was in love with lorelai, so your lesbian vision was actually pretty accurate! :)

The actress that played Gipsy said that she always thought that Gipsy had a crush on Lorelai… I thought they were gonna go for that when she popped the question.

I thought they were trying to imply that Taylor is gay? Maybe I miss read it..

I wish I were motivated enough to grow up to be queer Paris Geller *sigh*

Its not worth it. You will burn out and wind up writing about queer stuff on the internet… OK maybe its worth it.

I have a fundamental & stubbornly intentional misunderstanding of feminism and sexuality where I feel like at a certain point if you are as smart and driven and feminist and ruthless as Paris Gellar, you become queer because you just can’t even deal with the bullshit patriarchy anymore.

Are you saying this isn’t how it works? It appears that we have both been intentionally misunderstanding feminism and sexuality in exactly the same manner.

ilu

True!

That is absolutely how it worked for this bisexual

preach

YES

I’ve just started watching Goliath from Amazon, why isn’t anyone talking about it?

There’s SO MUCH femslash potential!

If some of that femslash potential involves Molly Parker, I will start watching it *tonight*.

It’s always nice to see articles from Kayla. I love her writings. Thanks. :)

Pretty sure it was a joke about Taylor being closeted, not much better but if you’re wondering what the point of the scene was I’m pretty sure that was it. The creator has said she planned to have a bunch of queer characters in the original but the network wouldn’t allow it. Sookie was originally gay. I agree though esp about Paris.

Oh my God, I want gay Sookie! I want to date Sookie!

oh and luke was originally a woman. Idk if luke/lorelai was still supposed to be a thing or not, but I’d definitely read that fic.

FLANNEL SHIRT AND BASEBALL-CAP WEARING, TACITURN HOT WOMAN AS THE FOIL TO LORELAI’S FLIGHTY QUIPS AND HER EVENTUAL BEST FRIEND AND WIFE

Oh my god yes

THAT show? I would watch.

LUKE WAS SUPPOSED TO BE A BUTCH WOMAN NAMED DAISY UNTIL THE NETWORK COMPLAINED THERE WERE TOO MANY CHICKS RUNNING AROUND STARS HOLLOW.

Seriously, this needs to be spread like wildfire. Everyone should know about this.

I DID NOT KNOW ABOUT THIS OH MY GOD

DAISY X LORELEI FOREVER

I felt very weird about that pride scene, and I didn’t get the reason until reading your article. I was very unhappy with that scene.

I felt like they had the set up for queer Paris, and kept thinking they were going there, but no luck. It for sure cemented my crush on Lisa Weil though. She is fantastic.

I think Amy Sherman-Palladino is on record for actively not liking diversity stuff. She wasn’t going to hire other writers; this is totally her baby and I assume she shuffed off the middle to Daniel. Sometimes I wonder if the person who casts extras is rebelling… There were a LOT more PoC in the background.

Also Gypsy is totes in love with Lorelai.

I do remember him having a writing credit on at least one of the episodes. I don’t think the casting of PoC actors was rebellion at all, though. I think it was absolutely intentional, and to me it illustrated even more just how out of touch the show is. The idea that inserting a PoC extra here and there is a reasonable attempt at addressing the lack of diversity on the show- they don’t get it. They’re not even trying to get it.

They don’t *want* to get it. At all.

(Daniel wrote the middle two episodes.)

I’m watching the show for the first time on Netflix (halfway through season 5) and in the lead up to the revival I found out that Luke was originally supposed to be played by a woman. As much as I love Scott Patterson it would have been SO MUCH BETTER if Luke was a lesbian. Imagine if the story lines were essentially the same- but the central romance was queer as hell. Missed opportunity.

Listen I still contend that season 1 should have ended with Lorelei and Rachel kissing. There was a pair with chemistry!!

I still don’t understand how a show that is all about the relationships between women doesn’t have any openly queer women. And that sooo much time in the revival was spent on ~boy drama~ ick. Also I read somewhere once that queer women were statistically more likely to have teen pregnancies. So put that in your pipe and smoke it.

Yeah, the statistics that show that LGBT kids are more likely both to become pregnant and to impregnate others as teens are well-established.

Partly because, hey, the B & T parts of that equation exist, and there’s a connection between having your identity denigrated and not having safe sex! And then there’s evidence that queer kids of all kinds are more likely not to prepare for baby-making sex, find themselves having sex from peer pressure or to “prove” a sexuality, and experience rape and forced sex at higher rates.

:(

Well, you’ve all been very encouraging that this is a show I should never see. ;)

THIS.

I mean, I’m all about watching complex relationships between women and mother-daughter relationships, but I can get that on Jane the Virgin without the racism, thank you very much.

It’s actually a [tele]play.

?

the revival filled me with so much rage and sadness. all these years later, and it was actually more regressive than the original. it’s like they read what was wrong with GG and doubled down on it. like they were nostalgic for a good old korean mom joke. i read an article about how this revival had a “white feminism problem” but it’s more like it has a white problem. there was nothing feminist about this show–i think it only passed the bechdel test because they talk about food so much AND THEN NEVER ACTUALLY EAT IT.

thank you for covering their absolute failure to free paris of her heteronormative chains and for offering a lovely space to complain about the show in the comments! my worst fear is that someone out there enjoyed this revival, so i’m really living for the hatred rn.

I listened to a podcast with ASP a few years ago, and one of the questions was what changes the studio made from the original pilot script, and the biggest change was that in the original script Sookie was gay. The WB absolutely refused, and only allowed Michel to be coded as gay. So the heteronormativity was baked in from the beginning by the studio. Obviously this is not a problem with Netflix, but it does high light the issue of nostalogia revival shows who had prejudices of the time seeded into their DNA and how to best update them.

I was disappointed that Paris didn’t start going on some ladies dates post Doyle (although I as most disappointed that Lane was treated as an afterthought still married to that idiot Zach and still stuck in Stars Hallow, and still friends with Rory the terrible).

YES THANK YOU FINALLY someone said it. I binged GG this summer and my biggest disappointment was Lane Kim not making it as a rock drummer when she worked her ass off to be one!!!! To me, that was also a rare chance to see a depiction of nontraditional adult artist family. T_T Probably the wrong reason to be mad but I’m still mad.

Lane Kim deserved better.

yes, both lane and paris were so hardworking, and in the revival both had such mediocre lives in terms of what they really wanted for themselves. even rory did cool stuff in the last season of the original–in the last episode, she gets to report on an up-and-coming senator named barack obama! but the ego of the team who did the revival just up and ignored the last season because they weren’t involved in it.

lane really should have moved on from rory…

That scene felt like ASP/Daniel sticking their tongues out at progressive audiences.

I’m very unsurprised at the way all of this went down — ASP is really against feedback of any type & “does what she wants.”

Eye roll. The racialized jokes were the worst. Mrs. Kim’s entire cameo is a tasteless joke about Asian immigrants? Yuck.

I did love the Luke and Lorelai stuff and enjoyed seeing the girls back in action, though.

There’s a scene in the Gilmore Girls reboot when Lorelai and the committee are getting a preview of Stars Hollow: The Musical and we watch Lorelai aghast at what’s playing out before her. But when the committee meets to offer feedback, Lorelai is stunned to learn that everyone loved the musical except her.

That’s how watching this reboot felt to me. There was so much fawning over Gilmore nostalgia and I felt like Lorelai sitting in Miss Patty’s studio.

Thanks for writing this critique of the show and for those sharing their own misgivings…it’s good to know I’m not alone.

It occurs to me that Lane had two kids and Paris had two kids and Rory is on the way to having kids, all at 32…here in Cali, that strikes me as pretty young? Like sure, we all had that friend who married in her twenties and got down to procreating, but there are a lot of women who wait until their thirties to have children, so it struck me as odd that both of Rory’s besties have two each in the revival.

of course they do, to highlight how ~special~ lorelai and rory are, because they do things ~differently~

lol for being single mothers? Is this 1965?

Oh wait, Stars Hollow is totally in 1965, I get it now

maidservant

Ugh so glad to see all this being talked about!! So many people I know loved everything. I also laughed at Taylor’s line, but I just overall super hate that scene thinking back on it, esp how they sort of pointed to how some people saw Gypsy and Taylor as queer and then just followed it up with essentially a ‘lol nope.’ Also, while I’m already ranting about things I hated, even though I love Luke and Lorelai and their wedding was super sweet, I also hated that they sort of played into Emily’s comments that partnership is meaningless unless you’re married. Like, I don’t mind that they got married, but I really didn’t like that it was kind of used to solve all their problems, and that no one ever really refuted that only marriage brings real commitment.

But whatever. At least Paris Geller is forever queer in our hearts. I saw a post on tumblr I think that Rory’s baby is really Paris’s via her surrogacy company and they’re about to embark on their new life together, and that headcannon = firmly accepted.

I would accept that headcanon except that Rory is The Worst and Paris (my love) can do so much better. Even I would be better.

It was so terrible. For all the reasons above and so many others I’m starting to forget them. And badly written, and badly acted! Rory’s character particularly–I kept going “what? wait, what? I don’t understand anything that is happening.” The old series had its problems, but this was just crap.

The thing about Gilmore Girls that gets me is that for the longest time I though I loved it because I identified with Rory. That doesn’t add up for a number of reasons, though, and I realized while watching the reboot (after watching the series in its entirety at least four or five times) that it’s about the way Rory is loved. She is the heart of the show only in that she is the subject of the love of all of these people.

The only times she ever develops as a character are when she does something so monumentally irresponsible and selfish that someone who loves her gets mad enough at her that she cannot face them (usually Lorelai). See: the time she slept with Dean while he was married and the ensuing incommunicado European vacation. See also: the time she stole a yacht because some blonde dude with a haircut told her she would make a better secretary than journalist. The reactionary pendulum swings too far; Emily incited independence and resilience in Lorelai and Lorelai incited none of that because she got gritty by being roughed up. So, Rory is privileged and helpless.

By the time 32 rolls around she doesn’t even have to have a home because there are half a dozen people who will house her and it’s not cute anymore. It’s amazing for a child to be loved like that but she’s a grown ass lady and she never had to become a real person. Why bother when you’re unconditionally adored by a New England hamlet? Maybe she writes a book about her mother and realizes none of it was an accident, it was a slog, and that she’s only really interesting by association with her mother. Because she’s yet to do much of anything else.

“Rory is privileged and helpless”

Yeah I think that just about sums it up.

Spot on.

Immediate suggestion for improvement: Lorelai decides to go to A-Camp to find herself instead of trying to do Wild.

Why do you expect/hope/wish for the show to be re-written to frame your particular minority? This is a show trying to reach a large audience.. if anything on balance it probably over-represented Queer characters. Why not be happy you were thrown a bone? I don’t get it.

My particular minority wasn’t mentioned once and I couldn’t care less but I enjoyed the experience, even if I didn’t appreciate various aspects and the ways certain people were portrayed (I agree with some of the comments about Mrs Kim- that was a very odd cameo).

4 years later. you better have changed from when you last wrote this comment. In no way are LGBTQIA+ characters “over-represented” wtf? In this show alone they mentioned Michele and 1 other random person. Every relationship in this show is straight and basically every other show too. The only shows I know that have an LGBTQ+ main character have been canceled. We are more common than you think and I’m tired of ppl saying stuff like this.

Why does everyone hate Rory so much? I never watched the show but it seems in the comments (and in the article as well) that really everyone hates her :D What did she do?

Lane needs to leave Zach (who is a *monster*) and date Paris. While it won’t work because, honestly, Paris is bonkers, Lane will learn what it’s like to be taken care of rather than have care used as a weapon to control you. Then she’ll be happy without the band of crappy man children and go find Dave ragowski and make it happen.

Who else noticed that Bailey Buntain aka the awesome and perfect Lauren of Faking It would’ve been a better Sandee??