С Новым годом! Suh novim godum. Happy New Year! Yes, this is a Jewish food column, and that was Russian, not Hebrew or Yiddish or Ladino. And why is something going up for the New Year? Traditionally, Jews have four New Years and the Gregorian one isn’t one of them.

Today we’re going to explore part of the Jewish diaspora the way many such pieces do, by starting with my family. My parents emigrated from the former Soviet Union, and I grew up in a pretty tight-knit community of Russian-speaking Jews, part of a big wave of Soviet Jewish immigration between 1989 and 2001, of which about 50% live in the New York area. Autostraddle has covered personal feelings from queer Russian folks: both asylum seekers in New York and a beautiful personal essay by Zhenia.

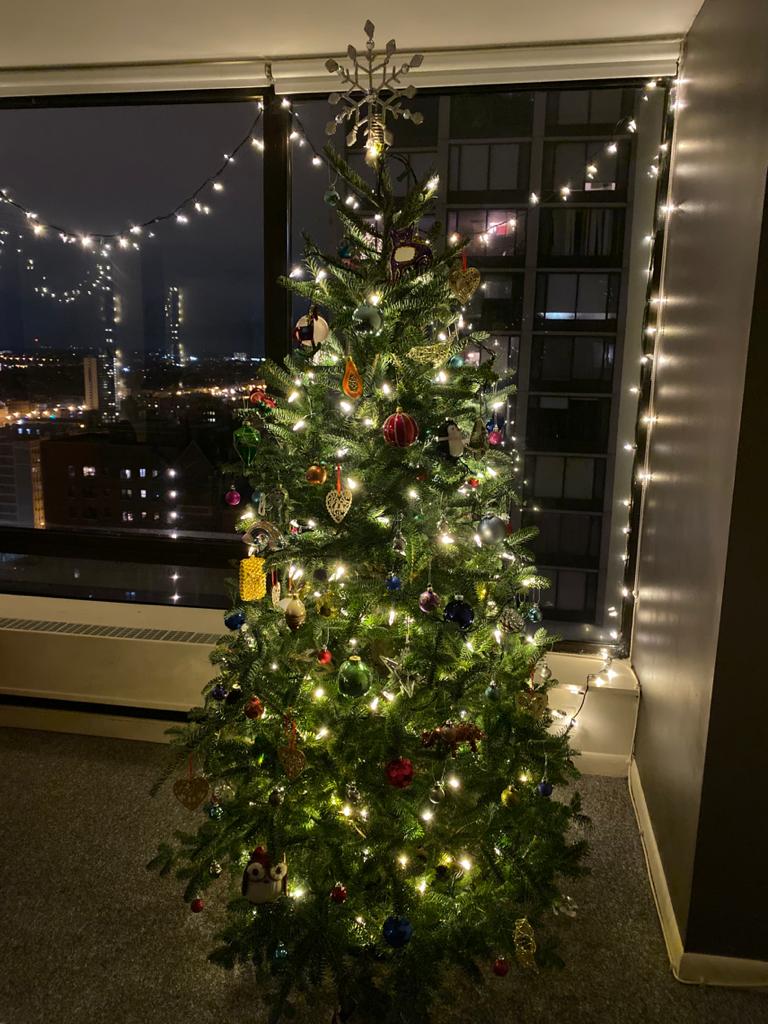

So let’s imagine: It’s the Soviet Union, an officially atheist state, so Christmas is out of the question. But as anyone living near Christians can affirm: people really, really love Christmas. So, what to do? Conveniently, there’s already another holiday less than a week later… so all the Christmas traditions got punted over to New Years, Novey God (nawv-ee gawd) in Russian. A yolka or fir tree brought indoors and decorated with ornaments, Ded Maroz (Father Frost) in red velvet with a big white beard who brings presents to children, accompanied by Snegurochka, a Snow Maiden helper. And, of course, lots of delicious food and drink with family and friends.

My summary is slightly glib and primarily informed by family legend; luckily, the actual history seems to line up.

New Year’s parties continue to be a Big Deal. There’s champagne, a yolka (for particularly frugal folks, scavenged from the curb of a neighbor who was getting rid of theirs after Christmas), gifts, and everyone dressed to the nines. Unlike American New Year, which is often a holiday celebrated with friends and excessive drinking, Novey God tends to be intergenerational friends and family. It involves gratitude, appreciation, and well wishes – the idea that you want to start the New Year with what you want to carry into it. There are many traditions of long toasts, poems, and informal talent shows.

I reached out to some queer Jews from the Former Soviet Union to hear about how they observe Novey God.

Irina Zadov, a queer Soviet Jewish refugee who immigrated at seven from Minsk, Belarus, describes: “In all my childhood memories, we would have a yolka, and there were very special foods we would have only once a year like oranges or peas. We would have tinsel and old vintage soviet toys. When we came to America in 1991, I don’t remember us having a tree, I don’t think we really could afford it, but after a certain time we got a plastic tree. My brother and I would get discount ornaments after Christmas and we would give them to our parents as gifts for Novey God.”

Irina describes a tension “of what it feels to preserve an assimilationist culture” – Novey God was a holiday explicitly created to prevent banned religious practices, and in the United States, it feels like a not-insignificant amount of Jewish identity is around not doing Christmas. My family didn’t put up a yolka, although many of our friends did. When I asked my mom about it for this article, she said that when some of the banned history became accessible in Ukraine, and even more so when she and my dad moved to the United States, they realized that it was a Christian tradition and stopped doing it. Still, many of our family friends (as well as Irina’s family) continued, and we enthusiastically celebrated the biggest holiday of the year.

Today’s recipe is pretty much The Novey God recipe: It’s hard to imagine a Novey God party without Salat Olivye. Salat Olivye is a deeply Soviet “salad” — the only hint of green is the peas, which traditionally were canned peas that are actually more… greyish. It takes a bunch of cheap, hearty, durable ingredients that were usually available in the winter among food shortages in the USSR and transforms them to create a delicious dish. Like many traditional recipes, they can change over time; Irina’s family’s recipe has evolved to reflect American ideas of quality: “When we were little it was always, doktorskaya kolbasa – heavily processed meat of unknown origins. Over time it became chicken, I know it’s not hot dogs now.”

It takes quite a bit of chopping for the massive portion that you would want to serve at a gathering. And even then, a festive spread wouldn’t be complete without at least twenty different dishes (zakuski) laid out. Everything should be carefully plated in the special dishes and well decorated. My dad carved radish stars to decorate our salads, which I tried to replicate; Irina’s dad would carve out little mushrooms out of eggs.

Salat Olivye

Ingredients

3-4 medium potatoes

3 medium carrots

6 eggs

3 dill pickles

1 cup green peas (frozen)

1/4 cup dill

2/3 cup mayonnaise

3/4 lb doktorskaya kolbasa (or bologna, or hot dogs, or 1 pack vegan bologna, or a few vegan hotdogs – you have a lot of options here)

1-2 radishes or hard boiled eggs (optional, for garnish)

Recipe

1. We’re going to boil the potatoes, carrots, and eggs. There are two schools of thought for this: boil first, then chop; or chop, then boil. We’re going to chop then boil because it both cooks faster and doesn’t require waiting for the cooked vegetables to cool before chopping. Like with latkes though, this is the sort of ratio where the ratios and methods can vary dramatically.

2. Chop your potatoes and carrots into small cubes, slightly under a centimeter. Boil for 10-12 minutes in unsalted water, check that they’re done before draining.

3. Meanwhile, boil the eggs to a hard boil. I trust y’all to have your own strategies, but if not, here are two approaches: (1) I am in love with my new InstaPot and made them in there using the 5-5-5 method, or (2) my mom’s approach: put eggs in the pot, cover with cold water, and bring to a boil. Once the water boils, leave uncovered until the water is cold. These were generally the easiest-to-peel eggs at the annual pre-Passover prep sessions, although I have to admit that the InstaPot ones are even easier to peel.

4. Chop the dill pickles into small pieces, smaller than the potato and carrot – they can be overpowering if too large.

5. Chop the meat into 1 cm pieces.

6. Once the eggs are cool enough to handle, peel and chop them. Sensing a theme here?

7. Defrost your peas, either by leaving them out while doing everything else, or by pouring them into a bowl of hot water and draining thoroughly after a few minutes.

8. Mix together all chopped ingredients and some chopped dill. Add salt and pepper to taste.

9. Optionally, carve some radishes or hard boiled eggs for decoration. The one my dad did growing up involves sticking a sharp paring knife about half way into the radish in a zig zag formation until it’s cut in half.

10. Serve in a ~very fancy crystal bowl~ garnished with dill and radishes.

Novey God takes place on December 31. Happy New Year!

Comments

Ah yes, the salat! I remember being asked to make this for Russian Club in college — the ingredients looked horrifying, but I can testify this is actually very good! So here’s a question that’s a bit far out, but you all may know the answer. The USSR made Novyi God a pan-Soviet holiday, including in Islamic Central Asia. The earliest photo I have seen of Novyi God in Uzbekistan comes from the mid-1950s in the newspaper O’qituvchilar gazetasi/Uchitel’skaia gazeta. You’ve got the New Year’s tree, Grandfather Frost, and little kids. . . dancing around in bunny costumes. What’s the deal with the bunny costumes?! I’ve seen other photos of this elsewhere. Spasibo!

So my guess would be that it was part of a tradition of having talent shows at New Years parties, but I’ll ask around and see if there’s other explanations!

I have an answer!! They were zaichiki, which are hares not rabbits. They’re a popular New Years motif/winter motif. Apparently they shed during the winter to turn white to blend into the snow (from their summer brown). There’s also a very popular chocolate that’s eaten at New Years named after them. Secondary possibility: everyone loved Nu Pogodi, a popular Soviet children’s cartoon, which had a rabbit as a main character.

Thank you so much! I have wondered about this for years. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty just ran a little photo gallery of how New Year’s replaced Christmas for the Soviets, and it starts with a 1963 photo of kids in bunny (hare) costumes.

Iranians also have salat olivye(spelled Olivieh), which makes sense since USSR was our neighbors & we currently share the Caspian Sea. The only difference is we don’t put carrots in it & use shredded chicken instead of deli meats. There is also the regional difference in the pickles used as we use Persian pickles vs the Eastern European style ones. I asked my parents how it got its name & was told it was named after a Russian dude named Olivier. We usually have it with lavash bread.

thanks for sharing, I love learning about different variants (and sounds delicious with lavash!) The wikipedia page has a fascinating history – turns out the original recipe has almost no relationship to what we eat now!

Thanks for the introduction to this holiday I wasn’t familiar with!

Happy new year!

This article feels like home! I’m also a Russian-Jew, my family have lived in Australia since 91 and Olivier has been a big part of festive meals over the years! I’ve never used meat in this salad, but used to eat big slices of kolbasa with butter in a sandwich.

There are so few of us publicly out, I’m glad to have gotten to share this virtual space with you!

Thank you, what a lovely thing to say!

ha–I just devoured some olivye and choked down the year’s first butter-and-caviar sandwich with my Russian in-laws! (Caviar is not my favorite, but I’m coming around to sprats. I made olivye for the first time this year and won lots of approval). I like “Russian Christmas” because we can visit my American family for western Christmas and then celebrate again, a week later.