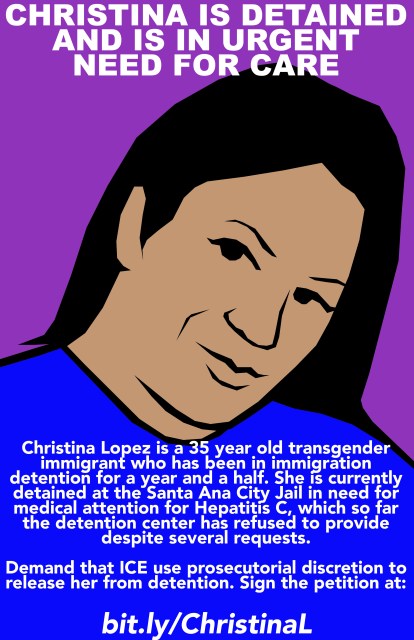

Christina Lopez is an undocumented Peruvian trans woman being held in a “GBT pod” in the immigration detention center in Santa Ana, California. She needs medication for Hepatitis C, but after repeated requests, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) continues to deny her access to them.

Lopez’s medical crisis is the latest in the ongoing denial of basic needs for trans women and other LGBTQI people in immigration detention. Hers is one of many cases which are leading LGBTQI activists across the country to demand freedom for LGBTQI people from immigration detention.

Earlier this summer, ICE released a memo announcing a shift in policy that moved towards creating different options for transgender women who have been detained in men’s detention facilities, even suggesting that there was a possibility that trans women could be held in women’s detention centers. Getting trans women out of men’s detention centers is an obvious win – it’s well-known that trans women face major amounts of sexual violence in detention centers, and it’s inherently transmisogynistic to keep trans women locked up with men in the first place.

Since the memo was released, however, it has become clear that this means the creation of new spaces called “GBT pods” in detention centers, specifically for trans women and gay and bisexual men. Lopez is housed in a GBT pod, and her case illuminates that they are not a viable alternative. “It’s been shown that ICE isn’t capable of caring for folks in general, but especially trans women. So that includes medical neglect, sexual assault by peers and sexual assault by guards,” said Jamila Hammami, Executive Director of the Queer Detainee Empowerment Project (QDEP), which supports detained and formerly detained immigrants in New York.

The only way for LGBTQI immigrants to be safe is for them to be released from immigration detention.

Jennicet Gutiérrez, an organizer with Familia Trans Queer Liberation Movement, publicly called on President Obama earlier this year to release transgender women from detention centers, and she said stories she had heard from undocumented trans women who had been in detention centers inspired her to speak out. She told Autostraddle, “With the mistreatment, the lack of medical care, and the horrible stories I heard when I spoke to undocumented trans women who were released from detention centers… To me it was very critical at that moment to raise my voice on behalf of the undocumented trans and queer LGBTQ community.”

“They treat us badly either way”

The theory behind GBT pods is that, since the people detained there will not be with the general population, and the guards will have special “sensitivity” training, they will be safe. But GBT pods are not a new concept, and they don’t have a track record that lives up to their claims of safety. The staff at the Santa Ana GBT pod, which has existed for several years, have been reported to have told detained trans women to “act male” or use their “male voice.” The same investigation by CIVIC found that women in the facility were frequently subject to full body cavity searches, often by male guards.

The ICE memo issued earlier this summer reiterated the need for proper training for those entrusted with the care of transgender women, however, there is little guarantee this will happen, or that if it does happen, it will be effective or administered with comprehensive oversight. Santa Ana’s GBT pod isn’t the only one with a spotty record. Around the country GBT pods, “alternative lifestyle tanks,” and other special units for GBT people have each found their own special ways to exclude, isolate and abuse GBT inmates. It’s all but impossible to find a story where GBT people haven’t been subject to harassment and abuse, whether or not they are in a special section, whether or not their guards have been “trained” on caring for GBT inmates.

So far, the public information about where GBT pods will be is limited. Reports from Hammami and Rita*, a currently detained trans woman seeking asylum, who was recently moved to Santa Ana, suggest that they’ve expanded the number of people at the GBT pod in Santa Ana. There is also a “makeshift” GBT pod in the detention center in Elizabeth, New Jersey. It seems that there is a larger GBT pod on track to open in Adelanto, California, which is about an hour and a half outside of Los Angeles. This has bad implications for people who will be detained there, as Adelanto is notorious for subpar medical care, and it is owned by a private company, which also makes for less transparency and accountability when it comes to conditions and compliance with ICE policy.

Rita wrote to me about her experience in the men’s detention center in Eloy, Arizona, and then in the GBT pod in Santa Ana. At Eloy, she was sexually assaulted on multiple occasions by guards. She was finally transferred to the GBT pod in Santa Ana, California this summer, but it is unclear if her transfer was a result of new ICE policy or because of action Rita took on her own behalf to demand her transfer. “Here we are only trans women… they are bringing more trans women from other detention centers and I think that’s good,” Rita told me. But she also said there seemed to be little concern over the fact that LGBTQI immigrants are considered vulnerable, confirming the continued practice of full body cavity searches. “They treat us badly either way, and without conscience,” she wrote.

“Support makes a difference”

In late August, activists and organizers from across the US and Canada came together at the second Queering Immigration conference, put on by QDEP. Groups included Mariposas sin Fronteras from Tucson, Arcoiris Liberation Team and Arizona Queer Undocumented Immigrant Project from Phoenix, Immigration Equality, Detention Watch Network, United We Dream, and Mason Dreamers, all of which work with the undocumented community in different ways. Connected to the conference, QDEP organized an action outside ICE Headquarters in New York City, demanding an end to GBT pods.

Several of the people who spoke at the rally shared about their experiences in detention. One speaker stressed the urgency and timeliness of the protest, pointing out that ICE is actively developing policy and protocol around detaining LGBTQI people.

The action called on ICE to release all LGBTQI immigrants from detention, echoing the calls from the Free Nicoll Week of Action earlier this year, as well as Gutierrez’s call to the president. This demand is directed at ICE and the president because immigrants are detained at the discretion of policy they create and enforce. Immigration detention is not the same as prison – people are held there not as a part of a sentence for a crime, but in order to contain them while their immigration cases are determined.

Also at the conference, Karolina and Joselyn, two trans Latina activists who work with QDEP and Mariposas Sin Fronteras, spoke about their experiences and gave tips to what would be actually helpful to trans women who have been or are currently detained. These ideas included helping people access basic needs, like housing, food and healthcare, raising money for bail funds, and visiting or sending letters to incarcerated LGBT people.

Karolina and Joselyn’s discussion painted a broader picture of the needs for undocumented queer and trans people – getting them out of detention is a huge and critical step, but making sure their basic needs are met outside of detention is a fight unto itself. Karolina and Josselyn discussed facing discrimination in their job searches, housing challenges and healthcare. Healthcare is a huge battle for undocumented queer and trans people. Trans and queer citizens and legal residents face huge barriers in the US healthcare system to begin with. Undocumented people are additionally excluded from government-funded healthcare programs like Medicaid, and can also be put at risk for deportation in hospitals and doctors’ offices, like we saw last week when Blanca Borrego was arrested at her gynecologist’s office after the office staff called the police because of her ID.

Gutiérrez also discussed the challenges facing trans women upon their release from detention centers:

“People are released from detention centers and there are very few resources we have at the moment. …When one of our sisters is released and she doesn’t have any family support, we come together as a community and we try to help them get back on their feet and reintegrate into society. But this is an issue that organizations have been working on throughout the US for the past two to three years. It’s nothing new.”

Many local groups do outreach through direct visitation and letter writing with people in detention centers. Gutiérrez spoke to the importance of that support: “That support makes a difference. I spoke to Jimela, who was in detention for about six months… she opened up about how much it gave her hope [to have someone reach out to her] and helped her feel really really good.”

But ultimately, Gutiérrez said, “I think one of the biggest things is to put pressure on [ICE] to release them.”

To get Christina Lopez the care she needs, Familia TQLM, Not1More Deportation, and GetEQUAL have organized a petition for her release. Their work continues alongside other groups organizing across the country, both to support detained LGBTQI immigrants and those who have been recently released, and to pressure ICE to end LGBTQI detention.

*Note: To protect her privacy and safety while she is detained and her case is open, Rita’s name has been changed. Rita’s words have also been translated from Spanish — special thanks to Audrey for helping with translation.

Comments

I know this is a wholly naive question but why is an asylum seeker in prison in the first place?

Detention centres are technically different from prison. Above, Maddie wrote: “Immigration detention is not the same as prison – people are held there not as a part of a sentence for a crime, but in order to contain them while their immigration cases are determined.” But also that doesn’t answer the deeper question of why things like that perpetuate.

Yeah, I mean like Carolyn pointed out, the detention system is a different situation than the prison system. They are really similar in terms of physical structure and design, but the Official Governmental Reasons for people being there are different.

Basically, ICE has all these policies that justify holding asylum seekers so that they can make sure they show up to their court dates – it’s worth noting that this goes against what’s recommended by international standards. Asylum cases can take years, and keeping people locked up until they are determined is traumatizing and isolating, and it keeps people from accessing resources like lawyers and other community support for whatever reason they are seeking asylum for.

Thanks for your question, @thecirrhosismachine – it’s a good one, one people should be thinking about more.

maddie, this was an amazing piece. THANK YOU.

thank YOU for reading!

Thanks for writing this Maddie, and thanks for doing such a wonderful job in doing so. It breaks my heart reading about how these people are being mistreated.

thanks for reading, Mey, and thank you for always helping me be a better writer.

Thank you as always for keeping LGBT migrant issues in the spotlight. Excellent piece.

i’m glad this resonated with you. thanks for reading!