BUTCH PLEASE is all about a butch and her adventures in queer masculinity, with dabblings in such topics as gender roles, boy briefs, and aftershave.

Header by Rory Midhani

Naming is powerful stuff. It’s an older magic, a potent magic. Give something a name and you are bound to it forever, with a red string tied between your heart and its finger. Names are the threads of intimacy, the words that usher us in and out of life. Nicknames pull us into friendships and bedrooms. They mark us as Other or align us with a clique. Many queer narratives invoke the rite of naming, because the act of naming yourself is also the act of re-birthing yourself, reclaiming yourself, peeling off the used husks of yourself and saying “This sticky part here, this is who I am”. Some of us cut away names like old bandages, or see the mirror image of families we’ve lost in names that are too tarnished to reflect. For some, the new name can say “I do not belong to the ones who hurt me or abandoned me. I belong to myself”. Or the name is a new word that is not weighed down by generations of color-coded baggage. This name removes its bearer from a history of gendered association. This name is all the bearer’s own. Some of us may have a single name, or many names, or names that they can only speak in safe spaces. They are all important, and they are all our very own.

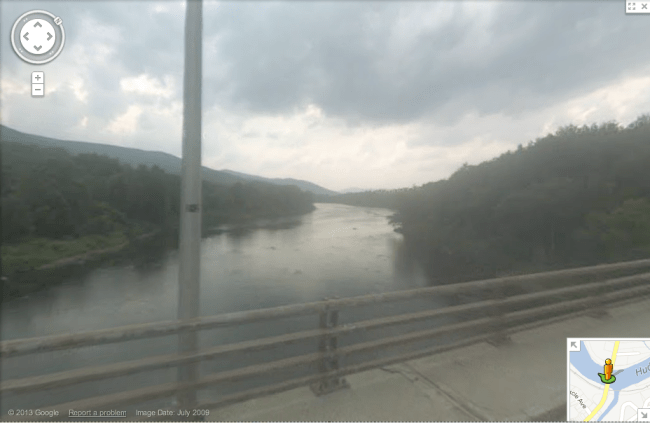

My first name was Hudson. My parents grew up in a small town along the northern Hudson River, near enough to the source that you could wade across in the summer and only get your ankles wet. I was raised along the same river, and soaked my calves in the same bend that my parents sat in as kids. The river there is many things: A force that gives and takes life, the source of simultaneous progress and limitation. It is wild and dangerous in the spring, but a welcome friend in the summer. It is limitless in all the ways I wish my own existence could be limitless, but still the determiner of boundaries, the decisive blue line that winds its way down the map, growing stronger as its path evolves. I look at the ebb and flow of my own life, my own identities and their constant desire to change and adapt, and I wonder if I did not take the river with me when I left.

According to my mother’s sonograms, there was no doubt I was a boy. Nurses and old wives alike said that my minuscule body had all the telltale signs. They knew it from the way I was carried, the rate of my growth, my mother’s cravings and my fierce little kicks. Most importantly, my boyhood was confirmed with the doctor’s absolute conviction of my tiny penis. I have seen it on the ultrasounds that my mother still keeps in her top dresser drawer, the phantom piece of me that did not find its way outside of the womb. I pray that this lost little penis rests in peace, wherever it may be.

This medical confirmation was enough for my parents. They would give me the name Hudson, for the river they’d known their whole life, as a reminder of my roots were I to grow up into the kind of man that finds himself in faraway places. They were thinking in blue and green, stocking up on jumpers with rocket ships and animals and bold colors that would complement Hudson’s inevitable coloring (as there are no blonds in my family, no blue eyes, and probably never will be). They were preparing themselves for the task of a son, and were often told how good they would be at raising a well-behaved boy, a boy with good manners who honored his elders. Hudson was going to be a handsome kid with his father’s looks and his mother’s convictions. He was going to hold doors and be a conscious citizen and have deep feelings for the women he loved and respected. They’d call him “Hud” for short, the kind of no-frills nickname befitting of a boy who knew his way around the woods. They loved him already. He would be the perfect son.

After 13 hours of labor in a heatwave, they did not get a son, or at least not in the package they’d intended. They got me. Or, they had always had me, and loved me, and been preparing for me, but the simple fact of my unexpected genitalia meant they could not call me their son, or Hudson. “It’s a girl” was as much a revelation as it was the label on the balloons being inflated in the hospital lobby. After panicked deliberation, my parents named me Kate. They both had grandmothers named Catherine, the saint who was martyred on a spiked wheel. My mother felt that Kate was the stronger and tougher version of that name. She said it reminded her of the women who worked in the lumber camps, keeping up with the lumberjacks and holding their own.

So, I’ve been called Kate for 23 years. I really do like this name, and the associations with it. It’s short and to the point, but it is not short for anything else, like most of the other Kates and Katies I have known over the years. It stands for itself, and by itself. It means “pure, clear, clean.” I remind myself of this over and over again when I feel broken, toxic, a thing stained by circumstances beyond my control. I don’t think of the name’s meaning as “innocence,” or the kind of purity that we have come to associate with patriarchal virginity. I think of my name as a pure essence, clean from toxins. The purest drink is also the strongest. And if I am anything, I am intense; my feelings always stab through me with absolute clarity, I am always throwing myself from one extreme to another. Kate really does seem like an appropriate name for my kind of existence, and I am grateful to my parents for that. The thread that my name ties to their hearts is one that is hardier than most.

By now, you know that I’m also called Kade. I named myself Kade. I didn’t want to stray to far from Kate and its reassuring power, but I needed to be my own. I needed to belong to myself. Over the years and the many things that have torn me from one direction to the other, my body has become less and less my own. In the process of reclaiming my body, I was realizing that whatever I was, it was not strictly woman. I was raised as a woman and have had the experience of a woman, or at least a certain kind of woman, but that label was neither comfortable nor without its escapes. At the same time, I knew I wasn’t a man, either, at least not all of the time. I was learning the most in my interactions with others. I didn’t feel like a woman making love to other women, and I especially didn’t feel like a man in the same position. I felt like a combination of the two, or something different from the two. I was, and am, Kade, but Kade is not necessarily male or female. Kade is neither, and yet both.

This is where I’ve always found such difficulty in describing my gender and my genderqueerness, perhaps because the language of gender is tied up in the binary and the movement between the two that it’s difficult even for me, in a body that is actively experiencing fluidity, to explain that I can be both and neither. I’ve always said that my gender is slippery, and it remains the best way to describe myself. I use masculine and butch when describing my presentation because the terms are, while not free from a gendered sort of association, not technically gendered.

I find it difficult to align my politics because while I call myself queer and know there is a certain queer politics that I often agree with, I still find myself relying on my experiences rather than my identity. I’ve had the experience of calling myself a lesbian, so I find myself gravitating towards that community, even if I don’t identify as a woman who is attracted to other women. I’ve had the experience of womanhood, especially socialized womanhood, so I gravitate towards spaces for women. I attended a women’s college. I’m invested in issues specific to these experiences, but now that my identity does not fall into any of these spaces, at least not firmly or constantly, I’m not sure where I belong. I’m not sure if it’s okay for me to be in lesbian spaces, or woman spaces, or any of these spaces, because I don’t identify as a woman all of the time.

I love the name Kade, and I love wearing the name, but it remains strange to slip in and out of it. Names, for all of their magic, are still very firm things. I go by Kade, but I also still go by Kate. I’m learning that we are not socially adapted to using more than one name at once, especially when they have two different meanings in terms of gender. It is interesting to note people’s reactions to my openness to use both female and gender neutral pronouns depending on the day, to feel comfortable using either of my names. Most people tend to stick to one name or the other when addressing me. I can tell there is a level of awkwardness in these actions, but I’m never sure how to explain that I don’t mind either without being afraid of insulting the firmness of someone else’s identity. There are so many terms for what I am – genderqueer, genderfluid, agender, pangender, neutrois – but none of them feel quite right. So Kade takes the place of that descriptor, and Kade feels right.

Maybe there will be another name in the future. Maybe someday I will grow out of Kate or Kade and into something new, or something familiar. I know I still have Hudson with me, even if it’s not the name I use. I was called Hudson, and maybe I will be called Hudson again, or maybe I only need to carry the river in my heart to carry its name.

Special Note: Autostraddle’s “First Person” personal essays do not necessarily reflect the ideals of Autostraddle or its editors, nor do any First Person writers intend to speak on behalf of anyone other than themselves. First Person writers are simply speaking honestly from their own hearts.

Comments

The way you write makes my chest hurt. It’s beautiful and painful and describes fluidity in better words than I thought possible. Thank you.

God I couldn’t have described this piece any better than what you just said.

This is perfect. I’m lucky in that my full name (Unyimeabasi; yeah, good luck saying that one) is gender-neutral, so I’ve never had the experience of it not “fitting,” but everything else, from the parents’ confusion regarding gender and naming to the question of identity, is all too easy to relate to.

Yes, I have this same thing with my first name (Nurin). It is technically gendered, but it’s Farsi/Arabic so nobody in the states really knows that and it sounds pretty genderless. I love that about it.

This column never disappoints. Thank you.

having a gendered name (and surname) has made me feel uncomfortable ever since i can remember myself and even now that i live in a country where people dont recognise my name as such i still havent managed to come to terms with it.

at least english is very gender-neutral and that makes it a comfortable language to speak. in my native greek together with pronouns, adjectives and participles are gendered too so you can’t say a lot more than hello without alluding to your gender. what was comforting for me when i was a kid was that nouns are also gendered. like, rock is masculine, stone is feminine and pebble is gender neutral. thinking of myself in the same category as a stone made me feel less gender-conscious and more comfortable with speaking in general. it made the whole gender situation seem absurd and funny to play with.

My mother is Greek, but i am not a fluent Greek speaker. As I struggle to learn the language, I’ve become very interested in how nouns are gendered, how rock became masculine; stone, feminine; life, feminine; death, masculine. Gender IS absurd….

it is very interesting, i think so. the earth is feminine and the sky is masculine and together they created life on earth in greek mythology. love is feminine but romantic love (eros) is masculine. light (phaos) and chaos, which signify everything and nothing respectively are both gender neutral and only seperated by one letter. myths and history can be traced with bare eyes. but then a busstop is feminine and a train station is masculine and youre like, what the hell

I have thought, “What the hell?!” when I think about gender in Greek. I wanted to study linguistics in college but thought it impractical, but I still like having discussions like this. Efharisto/thank you for indulging this.

I always found it funny that while “man”and “boy” are both masculine in German, “girl” is actually gender neutral. Das Mädchen.

Same goes for the old fashioned term for a young/unmarried woman: Das Fräulein.

Yes, but in German that’s more of a technicality. Nouns ending in -chen or -lein are ALWAYS das.

Still, it is quite interesting that a neutral word was chosen for “girls” I think. Boys are after all not called “Knäblein” or “Jüngelchen” or whatever. There are also a lot more words to refer to boys than to girls.

Another interesting thing is the fact that we call men “Herr”, but women “only” “Frau” instead of “Dame”.

I would love to know how all these things came about – language and naming are fascinating concepts!

Uuuh, I hate gendered language. After spending almost ten years in France, I still haven’t fully got it, people still correct my pronouns regularly.

I remember as a kid arguing with my French teacher about the use of pronouns : I decided for a while that I would only ever use feminine ones, because it was easier, and women were so much more cool than men.

that’s so funny! in finnish your name means “reversed”(?) as in “to turn inside out or upside down.”

ha, my full name is vassiliki but i might as well start calling myself reversed.

the sounds of finnish and greek are ridiculously similar sometimes. when we speak you will hear a lot of “kala” (good, okay) and “ne” (yes) and all our finnish friends can hear is “fish them, fish them”

I meant that girl whose name was Nurin. :) but you’re right, finnish and greek seem to have some words in common and the greek pronunciation is surprisingly easy for a finn. :)

This made me cry because it puts words to something I can never explain. People just don’t get it and I have never known anyone else in the entire planet to understand the confusion I feel inside.

I go by so many names; birth name-Kathryn, always been called-Katie, sometimes called-Kate, told people to call me-Kayden, was going to be named-Darryn. And when people want me to introduce myself I draw a complete blank.

It’s amazing how insignificant not having a name can make you feel, thank you for writing this fellow friend, it’s good to know I am not alone.

I am floored by your ability to eloquently explicate your journey. It took me until the ripe old age of 36 to understand and embrace my gender fluidity. The response and expectation of others unfortunately can still impact me in ways I wish I could better control. In my closet you will find dress shirts, slacks and ties lined up next to skirts and blouses all hanging above ballet flats and work boots. I float. This appears to be most unsettling for others depending on their expectation. The last time I wore a feminine blouse to work the response was so over the top I felt stripped bare, I shrank from my colleagues, I wanted to run right through the nearest wall -yet the same individuals don’t bat an eyelash when I wear a tie. If I was consistent in my outward appearance perhaps I would not be under such scrutiny.

In the end I guess the reason it is so important to share and put yourself out there the way you do is that it lets others know that even though others may struggle with their responses I don’t think any of us regret discovering, embracing, or expressing ourselves. If I like something I don’t worry about the judgement of others like I previously did. I bought the motorcycle, I cut my hair, I put on the muscle mass, and I wear the boy briefs (sometimes under a skirt). . . and you know what I am happy.

I can relate to this. I’m bisexual, and sometimes I have a masculine role and sometimes a feminine role with a partner, but this behavior has nothing to do with the gender of my partner, and nothing to do with whether I’m dressed femme or butch. I can be a dominant femme with a dude, or submissive MOC with a (femme) woman. These layers of gender identity can shift in me from moment to moment. However, I as much as I could relate to Kade’s amazing article (and those photos were so poignant!), I noticed I never feel like a mix (third gender or intergender). It’s always chocolate and vanilla swirled but still distinguishable, not a homogeneous … choconilla? or whatever. So, I once again have great appreciation for all the writers at Autostraddle helping us understand each other. I love u guys! <3 <3 <3

My parents named me Catherine with a C because my dads name is Charles and its a family name so if I were a boy I would have been Charles. But my parents hated the name Catherine so I’ve been called Cassie since birth because my initials are CAS but it says Catherine on my birth certificate. My entire family was really mad that my name wasn’t spelled Kathryn because I’m German…

Baby Kade smirk, I die.

” I’m not sure if it’s okay for me to be in lesbian spaces, or woman spaces, or any of these spaces, because I don’t identify as a woman all of the time.”

This. This. A million times this.

I have a hard time explaining this uncertainty to other people. I always feel like an invader or an imposter. Thank you for the reassurance that I’m not the only one who feels this way.

All said so well, and beautifully. You captured the nuances that can be so difficult to describe, more so because they can be very different for us, while strikingly similar. You’re describing difference in gender, and what you say applies to more of people that one might initially think.

I love “Butch Please”. Every time, you write from a point of view extremely close, when not exactly the same, as my own. Your articulate honesty is pertinent and inspiring. Is nice to know that there are other people out there that can relate to this “limitless something” we (try to) flow through. Can’t wait to read the next one.

I relate to a lot of what you say. My mom also thought I would be a boy, and then I wasn’t. I was going to be Jake, and well in a few months I legally will change my name to that. I also have the same not woman not quite man mixed feelings. When people don’t get it I just say I’m like a marbled cake. If chocolate cake is being male, and vanilla is being completely neutral, I am not all chocolate or vanilla. I’m not layered, vanilla and chocolate aren’t separate from each other. The flavors are swirled like in a marble cake, with about 60-70% chocolate and 40-30% vanilla.

You may be interested in the book “James Tiptree, Jr.: the double life of Alice B. Sheldon” by Julie Phillips. A fascinating woman who wrote science fiction about gender. She asked, in her private writing, “What is a woman, and am I one?” and that just got me in the gut, much like your writing here.

This is pretty much my life right now. Thank you so much for voicing it. My name is Emily Ann and it doesn’t feel comfortable to use or hear that name to describe myself, I actually got in an argument with my mother about it recently. No idea how to nickname myself to something more neutral from my birth names. Although I’m female-identified (perhaps incorrectly), oftentimes I absentmindedly forget my gender.

You could maybe try Em? Not a terribly common nickname, and it sounds like it could come from any of several differently-gendered names (Emily, Emmett, Emma, Emeric…)

When I was a teenager, I knew an elderly man called Jack whose given name was Evelyn. Apparently Evelyn was fairly common as a boy’s name around the time he was born. Since then, I’ve often thought it’d be cool for a woman with a really feminine, old-fashioned name to go by Jack.

The best as always. Thanks.

<3 this, & you, always.

thank you so much for writing this. i may direct people here when i’m trying to explain my gender. it’s kind of a magic feeling when someone else puts into words what you’ve always known in your head

This is amazing and perfect as are you.

you just put how i feel into words.

i swing between thinking about transitioning and also being totally fucked freaked out by that possibility and not wanting to rush into it. thinking about name changes and pronouns is too much for me at this point. beginning to identify as just butch has been a saving grace for my brain, even though most people would peg me more as hard femme from my appearance. butch feels safe. it doesn’t feel like a label that pushes me to be anyone or anything.

It’s for this reason that I absolutely love my name: Robin. I don’t hear any gender in it. I do wonder if I’d be any different if I had grown up with a gendered name, that perhaps our names affect us subconsciously. As for my identity… I’ve never felt like a “girl,” (what does that even mean?) and I’ve never felt like a “boy.” I’ve just felt like a person. So thank you parents, for sticking me with neutrality.

Yup, it’s a good name. I cut my own hair short when I was seven. My family moved a few months later and kids at the new school didn’t know if I was a boy or girl. Now I identify as a woman, but when I was a kid I felt pretty strongly that I was neither boy nor girl, that I was a tomboy, which I thought of as a different thing altogether.

As a name, Robin has its roots as a nickname for Robert, and when it started to be used for girls it was spelled with a “y.” These days I think there are a lot more girls with the name, with either spelling. I’ve worked with kids most of my jobs and independently of each other various groups of kids have nicknamed me “Bobby”… which I really like. Anyway, yes, a good name.

This is part of the reason I want to marry Robin Scherbatsky.

You write a beautiful article, but I admit I was kinda shocked by the bit where you summed up literally everything I’ve ever loved about my own name (Kate) in one amazing paragraph. I thought I was the only Kate who felt this way?? IDK its probably very trivial in comparison to the depth and complexity of what you wrote but I felt the need to point that out :)

I would really love it if you read your articles outloud. They are so poetic and beautiful. It would be great to hear it in your own voice

ergh but i sound like a little boy

I always imagine them being read in my dads voice… it’s very comforting to me. He’s one of these english gentlemen types who’s always reading the newspaper by the fire.

Can someone explain what MOC means?

it means “masculine of center” but to be honest i’m really not fond of the term for any number of reasons

I’m so excited to see you write about your name! Kade is the best name. I’m a Katherine (meh) who has always gone as a Katie but I’ve never felt uncomfortable with the name. I’m a total tomboy who loves nothing more than to wear my cargo shorts, 8″ tactical desert boots, and tank top, but I fluctuate somewhere in the middle of the spectrum. I can relate to and enjoy having other names that are based on who I am now not the tiny screaming infant I was at birth. My best friend growing up gave me the name Kade, almost always in context of “Hey Kade!” complete with a big so-excited-to-see you grin. That name to me is a happy place to be. I think it sums up who I was with her, who I wanted to be with everyone then, and who I am today. It’s a beautiful thing when you start to feel comfortable in your own skin and even better when you realize that other people find it sexy when you’re just being yourself. (It’s the combat boots, ladies… get’s ’em every time!)

Recorded at the Butch Voice NYC 2010 conference for an NYU radio class:

http://digital-goddess.com/music/butch_voices_3.mp3

Late to the party as always. But I really know what you mean with your name variation. I’m still in the process of accepting that there is a genderfluid aspect of myself, I never felt entirely feminine but was always uncomfortable being misgendered as male. My Sunday name actually sounds more masculine than my adopted name of Kali, but I often go by Wolf to close friends too. Wolf is something neither male or female but all the elements of strength and freedom and independence that I covet. Just knowing there’s other people out there having similar experiences is enough to make me smile when I feel like the whole world doesn’t fit properly on me xxx

I definitely did notice people calling you “Kade” in the comments, and then I’d be confused because when I scrolled back up to your picture, it said “Kate”, so this cleared things up considerably. :B I feel kind of stupid now. But that’s okay.

I feel like I’m very lucky in that my name is so flexible. I mean, I usually introduce myself as Samantha, but people invariably call me Sam, even when they haven’t even gotten a chance to know me yet. Which sometimes seems kind of annoying because it feels presumptuous to call someone by a nickname they haven’t offered when you’ve just met… but it’s also kind of freeing. Sam is so fluid in its connotations, and no matter how I’m feeling that day, it usually feels pretty right. It’s kind of crazy how that worked out.

Also sometimes I feel really sad that I’ll probably never meet you, and that even if I had the chance, I’d probably be too scared of making a fool of myself to actually say anything. I don’t know which is worse!

Loved the essay and the way you’ve found to move between different identities depending on how you are feeling. A few years ago I really owned my masculinity and what it means to be a butch woman. I’ve struggled with it in the past, wondering if I was trans but not really feeling right about that either. Once I acknowledged that I was a masculine woman and that it was okay for me to have that identity (more for me to be okay with it not that others had to be okay with it) I’ve enjoyed more freedom and joy in being myself than I have ever experienced before in my life. I think it’s powerful to have butch voices like yours out there saying that it’s okay to be who you are and whatever that means to you.

I am a MTF spouse of a GQ and you and per are pretty similar in many ways.

I am very happy to see other people who are similar to per becomeing part of the public view. It is proof that ze is not alone and it is ok that ze is not binary. For some time there ze was alone. The only one we knew or ever saw who was GQ wwas my spouse.

In the last few years of non-binary visability have been so good for per mental health. Knowing you are not actually wierd or that differant from others of your gender and that there is an entire group of folks that you have alot in common with is a real settler of the wild emotions.

:)

“There are so many terms for what I am – genderqueer, genderfluid, agender, pangender, neutrois – but none of them feel quite right. So Kade takes the place of that descriptor, and Kade feels right.”

Dude this is literally my life. I don’t know what I am. I’m genderqueer, gender-fluid, but mostly just Eligh.

My name, by birth, is Emily. And I can’t stand it. It doesn’t fit me at all. I don’t hate it, but I hate being called it. It actually stings to be called by that name. I’ve been told my name is pretty, which is not me. I can only appreciate that I share the names of Emily Dickinson. Frankly, some days I am Haleigh (not as feminine to me in light of Wolf Haley’s character), and other days I am Ivan. I haven’t dared tried to explain this to anyone in person, though. I am fine with simply “Wolf”.

This is so beautiful.

“I’m not sure where I belong. I’m not sure if it’s okay for me to be in lesbian spaces, or woman spaces, or any of these spaces, because I don’t identify as a woman all of the time.”

i feel this way a lot, actually. sometimes i feel like its a crime for me, a butch agender-ish bi girl, to be in lesbian spaces. like im an intruder. i feel immense guilt over all of my labels, like im not queer enough, not gay enough, not trans enough, and not butch enough. every month or so i rifle through autostraddle articles for the one piece of external reinforcement that will tell me it’s okay to be me, that i’m not hurting anyone. it tears me apart. im literally crying right now.

I have felt the same things and fall in a similar place as you.

Agenderish for the most part masculine bent bisexual.

You are you and that is enough.

You’re queer and you belong here.

Who you are, and who I am hurts no one.

thank you, that really means a lot to me right now. <3