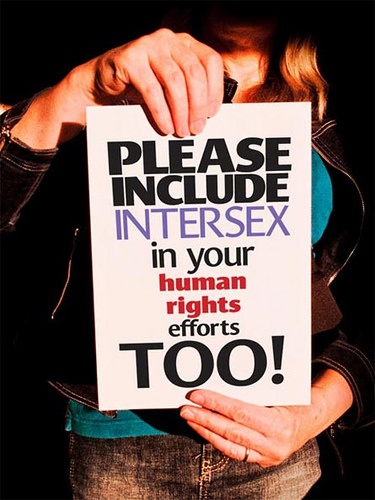

Hello there, lovely Autostraddlers! I’d like to continue the conversation on intersex issues, and hope you’re down to discuss and share. My first post served to define intersex and talk broadly about what intersex is, why intersex bodies are controversial in so many societies, why non-medically necessary treatments (e.g., surgeries, dilation procedures) are routinely performed on young intersex kids without their consent, and why these procedures – which are nothing short of human rights violations – need to end.

I was completely overwhelmed, in the best possible way, that so many of you responded so positively to talking and learning about intersex issues. (Thank you, thank you, thank you all, for being so awesome. My heart exploded a little bit the day that post went up. <3)

via Claudia

I think the next logical thing to address, after talking intersex basics, is this: What does intersex have to do with LGBT stuff?

I’m a little bit biased in wanting to talk about intersex issues on AS, because I’m a queer lady and I love this site and want to see intersex folks — like me — represented in spaces I identify with and care about (duh). But it’s more than I’m intersex and I like AS a lot; I think that intersex issues are becoming increasingly relevant to talk about in LGBT contexts, so much so that people are slowly, gradually starting to add the “I” to make this acronym: LGBTI.

So, why are intersex issues being linked up with LGBT activism, and does this make sense? I’m here to argue, strongly, that yes – including intersex with LGBT and queer issues makes perfect sense. Let’s explore why, shall we?

via sodahead.com

The goals of intersex activism broadly fit in with the goals of LGBT activism. Intersex activism is really young — about two decades old in the UK, and a couple of years less than that in the U.S. Intersex people began to break through the shame and stigma of their secret medical histories and share their stories and experiences with one another. They realized that bodies like theirs, and the procedures those bodies were forced to undergo, were actually a lot more common than they had thought. There were a lot of intersex people who had physical and emotional scars from the medical “treatments” that didn’t track their health, and couldn’t be reversed. They started to organize and speak out, telling physicians and the media that these procedures weren’t necessary, that they never consented to them, and that the after-effects of “treatment” caused more problems and confusion than their natural bodies could ever do.

via intersexualite.de

These people were so brave for thinking of these first conversations. The moments that intersex people began to realize their experiences weren’t total anomalies — that there were others who hurt, felt, hid and wondered for so long like them — is so powerful that I feel kind of nauseous. It’s hard to accept that these conversations had to happen, that this stuff was going on, and is still routinely going on even now. Intersex activism is relevant, and needed.

There are a lot of goals that intersex activists have that are specific to intersex people, and not to LGBT people broadly: raising awareness that intersex exists, accurately defining intersex, explaining that intersex bodies aren’t abnormal, that biological sex doesn’t come in just one of two flavors and advocating for intersex people to choose what is done to their bodies by ending non-consensual cosmetic procedures. These are not necessarily common goals all L, G, B, and/or T people are invested in fighting to change, or are affected by in their daily lives.

But LGBT people and other just-as-important groups that don’t (commonly) have their own letter, often have their own aims in what they want people to know, understand and accept. Broadly, I think that LGBT activism — despite our various bodies, sex and gender identities and orientations — accepts that we have the right to live our own lives as we want to and make our own choices. It recognizes that we are just people that deserve the same freedoms as everyone else and not labeled as “different” for arbitrary, illogical reasons.

And I think that intersex activism very clearly falls in line with those aims.

People question whether the “I” should be added to the LGBT acronym, whether intersex really belongs: It’s not really a sexual orientation, is it? It’s more about bodies and identity, right? Is it not okay to link up intersex people with queer communities in case a majority of intersex people happened to identify as straight? A lot of the same points and counterpoints people are making to support/discourage intersex inclusion are the same ones people were making a few years ago regarding trans* inclusion. Trans* is not a sexual orientation like L, G, or B is, either. From outsiders’ views, trans* seemed more related to bodies, and identities outside of L, G, and B. Trans* people are rightly included in the acronym today because they are perceived as outside of mainstream sex and gender norms, and their rights and identities need to be advocated for. This also means it isn’t necessary for a majority of intersex people to identify as queer in terms of sexual orientation or gender identity to join the club. I would encourage intersex individuals who are really, super-duper opposed to intersex inclusion to examine if, whether consciously or not, it’s because they’re holding some queerphobic views that makes them want to distance themselves from Gay Stuff. Because that is simply not cool.

via www.tumblr.com

Intersex inclusion makes sense. We need our rights and identities to be advocated for, like other LGBT groups are trying to do. Not being allowed the agency to make basic decisions about what is done to our bodies (i.e., being able to keep all our body parts intact) is simply not acceptable. Trying to erase our intersex by changing our bodies into those of “real” boys and girls doesn’t turn us into real boys and girls; it just changes our external appearance and very likely fucks us up in the process. For the first time, legislation is being drafted – and even passed! – identifying intersex people as a minority group with specific needs, that require legal protections against discrimination against us. Our legal protection is also being fought for in court, one important example being the the M.C. Crawford case, where Crawford’s non-consensual, cosmetic genital surgery was just declared unconstitutional for federal court. This is a huge step forward for intersex rights.

People still largely don’t know what intersex is, but more people I meet today have heard the word than I did four years ago, when I became involved in intersex activism. People sometimes look surprised or furrow their brows when I use the word “intersexphobia,” but I think this word will be known and used someday. People aren’t always aware that intersex medical procedures are so routine today, but I’m encouraged by how often people respond with shock and outrage and ask how this stuff isn’t illegal already.

It’s possible that I’m being all glass-is-full-and-overflowing with regards to intersex activism, and I’m in for a heaping plate of disillusionment sometime in the future. But I really don’t think so. More intersex activists are speaking out than ever before, and I think that even if intersex medical “treatments” don’t end within my lifetime, the knowledge that intersex people exist and should be protected will be.

Another reason intersex should be included in queer activist efforts is that homophobia partly drives intersex “treatment” decisions. It is sobering and deeply disturbing to understand how much intersexphobia is related to parents’, doctors’ and societies’ fear that intersex = gay. People think that if our bodies are cosmetically – even surgically – altered into a body that better conforms to subjective male/female beauty standards, this will somehow prevent intersex kids from growing up liking people of the same sex they were assigned by their parents/doctors. I truly don’t understand this thought process at all. If I have an adorable mouse, but I really wanted a hamster, cutting off the mouse’s tail isn’t going to make it a hamster. All I have now is a mouse that’s tailless.

via genderexpansionproject.org

Nobody knows who their kids are going to be when they grow up. Nobody. Parents may have ideals about what they’d like their kids to prefer, do and act like. Society has ideals about what citizens should be and act like. Guess what, though? Everybody is their own person. Not only don’t they have to conform to other peoples’ expectations/desires for them, but they AREN’T going to meet all those expectations/desires for them, because that’s not how being your own person works. I am fairly positive my parents would have preferred to have an easier time not worrying about what it meant to have a baby that is not typically male or female, and what do you do about that? But that’s not what happened. They had me, and that’s part of who I am. You love your child and accept that they’re going to be who they are, and do your best to support them in who they are, and that’s it. That’s how it should work. It doesn’t always work that way in practice, but it should.

via facebook.com

Parents often don’t want their kids to be intersex. They don’t want to deal with not knowing how their child fits into society in one of the most basic ways we use to categorize people. They are afraid of what it means for their kid to not be strictly male or female – something explored in-depth by Katrina Karkazis in her book, Fixing Sex: Intersex, Medical Authority, and Lived Experience. Will it be possible for them to be raised as a boy or a girl? If their child has genitals that don’t conform to strict standards of what typical boy and girl genitals “should” look like, will other kids somehow see and tease them? What would the babysitter say – can they leave their weird kid in the company of others who won’t understand? They don’t want to think that their child is “that” different, that children like theirs might grow up to be adults that are “that” different, walking around in the world outside, doing god knows what defying all the social norms that exist. It’s too much. Lots of parents can’t sign on for that. It’s easier to believe that changing their kids bodies’ will somehow magically translate into their kids being the “normal” kids they were supposed to be in the first place, and now everything will be just fine. When in actually, we were already normal and just fine to begin with.

via chelleshockk.wordpress.com

One thing that many parents unfortunately do not want their children to be, is gay. By “gay,” I really mean not-straight; whether parents conceptualize sexual orientation as binary or for the diverse cornucopia it is, what they have in common is that they want their kids to be straight. A lot of parents still see being not-straight as something that can or should be changed. (And if it can’t, they should at least be able to prevent their kids from “acting on” their homobigayqueerness, ugh.) Things are complicated by the fact that in our society, we typically conflate biological sex with gender identity, and gender identity with gender roles, presentation, performance, sexual orientation, AND sexual behavior. So, pretty quickly, intersex bodies cause a lot of social panic – another topic well-explored by Karkazis in Fixing Sex . Not only are intersex bodies themselves perceived as threatening in that they blow up the concept of biological sex as binary, but they evidently suggest that that someone with atypical sex characteristics might also have non-standard (i.e., unacceptable) gender identities, roles, etc…including sexual orientations. There are no indications that being intersex and being queer are causal, or even directly related at all, but the way our society links up these identities, it’s a pretty short jump from, “My kid is intersex,” to “Shit, my kid might be gay, too.”

We’re seeing the results of this kind of thinking with regards to prenatal testing. Pregnant parents-to-be can actually screen their kids for certain kinds of intersex, with the idea that if the growing fetus has an intersex “medical condition,” they can know about it in advance/use that information to make decisions about whether or not they want to bring the fetus to term. Expectant parents whose fetus tests “positive” for certain forms of intersex sometimes ask if their child is likely to be gay due to having this “medical condition,” and sometimes terminate pregnancies because they would rather have a kid who won’t maybe be gay someday. As I stated in my last post, I support any pregnant persons’ right to make decisions about their own reproductive health, including whether or not to end a pregnancy. I think it is seriously misguided, however, to abort a fetus simply because they might be gay, or will have intersex bodies. At best, this is ignorant. At worst, this is getting into the eugenics category – trying to prevent gay and/or intersex people from existing because we’re perceived to be undesirable or bad or somehow less-than. The link between intersex and homophobia is real and fucked up.

via blog.rti.orgtw

Homophobia also informs what “treatments” clinicians recommend to parents and perform on intersex kids. Female-assigned intersex kids’ external genitalia are surgically altered if the clitoris is deemed “too big”; developmentally, the clitoris and the penis derive from the same tissue (i.e., the phalloclitoris), and there are no absolute rules regarding at what length that tissue stops being a clitoris and when it becomes a penis. (Though multiple guidelines have been created by doctors for just this purpose, with – surprise! – different size ranges for clitorises/penises.) For female-assigned intersex kids, this tissue is reduced to a size considered typical or acceptable for females to have, even though research and intersex peoples’ accounts indicate that such surgeries leave lasting scar tissue and may result in lack of (sexual) sensation or even painful sensation. Basically, it’s more important that your junk looks a certain way so as not to freak out your opposite-sex sex partner, instead of prioritizing your capacity to enjoy sex as an adult and your rights to basic autonomy about what is and isn’t done to your body.

There’s also some really huge assumptions being made here about what kind of sex you want to have, and with who. Like, not everyone likes penetrative sex. What is the point of performing dilation procedures and/or reconstruct vaginal canals if the individuals don’t want to have that kind of sex? Why alter someone’s phalloclitoris size if they would’ve been happy with their body the way it was? You know? Surgery clearly limits the kinds of sexual pleasure intersex people can enjoy in their adult lives, in part by making big assumptions about who they’re going to share this pleasure with.

Clitorises have erectile capacity just like penises do, although when erect, they’re not as big as penises typically are. I think some doctors and parents are freaked out by the idea of a woman with a clitoris whose form and function remind them of penises. This woman is likely seen as “too masculine” to have sex with a man without calling forth images of gay sex, and sex with another woman would be, in fact, “gay sex” (although the individuals actually having sex might not identify it that way, blahblah but you know what I mean, right?). That would make that kind of sex unacceptable from the get-go, while also suggesting the disturbing possibility that such a female might be capable of penetration, or having sex “like a man.” (Some female-identified intersex folks – awesomely – can do this. I’ve never heard any complaints reported by themselves or their partners.) While you’d think this latter hypothetical might actually make the queerophobes feel better – since, to them, it might look something like the heterosexual penis-in-vagina kind of intercourse deemed the Most Acceptable Kind of Sex – it doesn’t. It freaks them out just the same, if not more so.

via www.gottman.com

Female-assigned intersex kids’ vaginal canal size is also assessed by doctors, to ensure that it’s long enough to fit a penis inside of it. Doctors might surgically construct or re-construct vaginas, which can result in a host of health problems and necessitate multiple, multiple surgeries. This is especially the case since most intersex kids have these surgeries very young, and when their bodies grow into their adult forms, more surgeries are necessary to keep their vagina size in proportion. Non-surgical methods are also used to increase or maintain vaginal length by regularly using medical dildos to stretch the vagina over months and years. (It’s kind of like braces for your vagina, but much, much worse.) Just like there are no standards for how long a clitoris “can” be before it’s classified as a penis, there aren’t absolute standards as to how long a vagina is for it to be of “normal” length.

I had a dilation procedure performed for almost every exam I had with intersex doctors from the time I was 8 until I was 16, so that they could check how long my vagina was as I grew. I absolutely hated these procedures. I mean, imagine a man as old as your father or your grandfather, who you don’t know, inserting a medical dildo into you each time you saw him, knowing that you can’t question the doctor’s orders and just accept that you have to undergo these uncomfortable procedures for your health. Imagine a decade or so later, realizing that these procedures did nothing to track your health, and had everything to do with grown men feeling good about the fact that you could fuck some dude someday like a “normal girl”. That all those traumatizing procedures weren’t actually medically relevant at all, and it actually was within my right to refuse those examinations.

I didn’t know any of that at the time.

I also had no idea that I wouldn’t want to ultimately have the kind of sex they assumed I’d be having, adding yet another layer of this-was-totally-unnecessary/messed-up to my history.

Other kids shouldn’t have to go through this. Other adults shouldn’t have revelations some day far into the future that what was happening to them WASN’T okay, and their traumatic feelings ARE valid, and the whole system of how intersex people are conceptualized and “treated” IS entirely fucked.

via hopeforyourfamily.com

And it’s gotta change. We’ve gotta change it.

There are so many reasons why adding the “I” to LGBT activism makes sense. The “I” isn’t being included too much at present, since people are mostly still figuring out that the “I” exists at all, and what the “I” means, exactly. And that’s okay. Change is slow. It takes a while to incorporate new stuff into our vocabularies, and eventually, our consciousness and world-views. But already, some activist centers are and college groups are dubbing themselves “LGBTI.” People I don’t know occasionally post things about intersex on Facebook, saying, “Wow – I can’t believe this stuff is (still) going on.” It’s encouraging.

Intersex isn’t well-understood now, but in a few years people are going to be much more aware and informed about intersex issues. Intersex is something we have to know about and think about – that it’s inexcusable not to – and understand what is at stake if we decide to remain ignorant about the medical system that is altering young lives every day for the worse.

via www.doobybrain.com

Adding one letter to the LGBT acronym –of the many other letters that could and should be added, knowing that it is difficult if not just plain impossible to be all-inclusive, qualifying and challenging every problematic aspect of the acronym and all the activism around it to death – might not seem like a lot. But in doing so, that’s sending a powerful message to all who see it: this is important enough to be included.