Autostraddle Chief Operating Officer Brooke Levin loves talking business. She talks business to sleeping interns, doormen, and strangers in bars. She talks business in a box with a fox, in a house to a mouse; here, there, and everywhere. While the rest of Team Autostraddle is transforming xeroxed copies of our favorite poems into magazine-construction-paper collages, Brooke is talking business. More or less to herself.

Autostraddle Chief Operating Officer Brooke Levin loves talking business. She talks business to sleeping interns, doormen, and strangers in bars. She talks business in a box with a fox, in a house to a mouse; here, there, and everywhere. While the rest of Team Autostraddle is transforming xeroxed copies of our favorite poems into magazine-construction-paper collages, Brooke is talking business. More or less to herself.

See, women are 57 percent less likely to become entrepreneurs than men, which means it can be lonely out there for a lady seeking participatory conversation partners. In 2006, there were only ten women running a Fortune 500 company, and onl 20 in the top 1,000. Furthermore, gay women specifically face unique challenges in the marketplace; combating sexism, homophobia and often also racism.

But that’s changing. Women are rapidly catching up. Between 1997 and 2006, businesses fully or majority women-owned grew at nearly twice the rate of all U.S firms. In “Brooke Means Business,” Brooke (and occasional guest-bloggers) will be talking to role models and trailblazers prepared to speak about added value, executive summaries and double bottom lines.

This is the future of women in business — the big dreamers, the moneymakers and the social changers… I hope you’re paying attention.

Curve was founded in 1990 by a then-22-year-old Franco Stevens, who wanted more than anything to find a National glossy magazine that said something — anything — about the kind of women she knew. She couldn’t find what she was looking for and so she started her own.

Curve was founded in 1990 by a then-22-year-old Franco Stevens, who wanted more than anything to find a National glossy magazine that said something — anything — about the kind of women she knew. She couldn’t find what she was looking for and so she started her own.

Her only industry experience was a stint at her school’s newspaper, and her only source of income was a bookstore job. Unable to get a bank loan for something as foolish as a lesbian magazine, Stevens cashed out nearly a half dozen credit cards and had enough to print exactly three issues. She literally bet it all on the success of her venture — and she hasn’t looked back since.

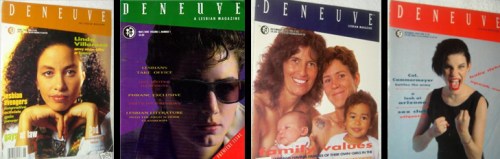

From its humble beginnings as a ’90s zine, Curve has grown into the nation’s best-selling lesbian magazine, read by more women than any other national gay or lesbian publication — all while remaining independent of corporate ownership. Curve was originally called Deneuve but changed the name to Curve ’cause of this lawsuit thang with French actress Catherine Deneuve.

Covering every aspect of lesbian life, from Small Town U.S.A. to West Hollywood, the quality of its content has kept Curve at the top for 19 years and has won acclaim from actors, authors and media outlets such as the New York Times and the Chicago Tribune, who have called the magazine audacious, hip, sexy, well-written, sophisticated and politically astute. It has been named Best Gay and Lesbian Publication by GLAAD and took top honors in Best Rock Reporting for their behind-the-scenes profile of Melissa Etheridge. In a time when the death of print is mowing down gay publications left and right, Curve had the presence of mind to come out with a digital edition and is now one of the few publications who can say it’s keeping its head above water.

Most importantly it’s kept up with political issues and other interesting things happening in the queer community while keeping coverstory heavy-hitters like Tegan & Sara, The Indigo Girls, Rose Rollins, Michelle Rodriguez, Leisha Hailey, Katy Perry, kd Lang, Melissa Etheridge, Le Tigre, Kate Moennig, Laurel Holloman, Mia Kirshner, Alexandra Hedison, Jackie Warner, Daniela Sea, Jamie Babbit and Aubrey O’Day.

The story of Curve is an amazing testament both to Stevens’ determination and the support of the community — from her beginnings as a bookstore clerk with an idea to the 300 women who responded to her call for writers and photographers in just one month. No one knows better than us that it’s hard out here for a lesbian publication, but without Franco Stevens paving the way it would be almost impossible. If you want to know what a lesbian entrepreneur looks like, it’s Franco Stevens at age 22 standing on a street corner in the Castro peddling paper copies of the infant that would become Curve. Every queer lady (and especially every queer lady journalist) has Franco to thank for teaching us all the meaning of “If you want it done right, do it yourself.”

Brooke: What was the stimulus behind launching Curve?

Franco: Twenty years ago, the environment was much different. The lesbian community was really disjointed, most people weren’t out, couldn’t be out in their everyday lives, and they didn’t have any positive representation of themselves. So my stimulus for starting the magazine was partially selfish because I wanted it myself. And partially because I knew that there was a need for it in the community, a need to represent all aspects of lesbian life.

Brooke: Often, women focus on the disadvantages of being a woman in the business world. What advantages have you found?

Franco: I think the advantage to being a lesbian woman in business is that sense of community. Now, when I was 21 years old and had a business plan to start a lesbian magazine, it was a little bit different. People were like, “You’re gonna start a lesbian magazine? I don’t necessarily think that’s a good idea.” But as I started to gain momentum, the community slowly got behind the magazine. That’s why we’re one of the few publications that have been able to survive for this long.

Brooke:: Why do you think lesbians are still such an untapped market? How does Curve change this?

Franco: I think, more than anything, that gay men are seen as trendsetters and early adopters, whereas lesbians aren’t. They aren’t seen as cutting-edge in anything — fashion or technology — and the media has a lot to say about that. So we feel it’s our responsibility to help change the perception in the world and not just complain about it. That’s been the theory of the magazine all along: if you want something done, you have to get out there and do it. Don’t just expect someone else to change the world for you.

Brooke: What was the largest barrier to growing or starting your business?

Franco: The financial one was huge. We were in a recession when I started the publication 20 years ago. Magazines were failing left and right, like they are today, and trying to raise the capital to start a publication — especially a lesbian magazine — was extremely difficult. I figured, “Oh, I’ll write a great business plan, I’ll go to the bank, represent myself as a woman in business.” And I got shooed away. “No no no no no no no.” Heard a lot of no’s. I heard a year’s worth of no’s, but I’m tenacious. I figured out how to save my money: take out a bunch of credit cards, cash them all in, go to the race track. I ended up having enough money to start the magazine.

Brooke: And how did it grow from there?

Franco: A lot of bookstores wouldn’t even agree to take the first issue because it was such a wild, crazy idea. Once I had an actual copy in my hand, I could send it to magazine outlets and distributors and newsstands. I was out there on Castro Street in San Francisco, standing outside of a bookstore where I worked at the time, selling individual copies to women walking down the street.

When I got the idea for the magazine, I was like, “Ok, now I need women to be involved.” So I put up a little handwritten notice in the entry-way of the bookstore that said, “Writers and photographers wanted for new lesbian magazine.” And I got 300 calls in a month, so I knew that there was a need for the publication, even outside of the women who would walk into the store asking, “Hey, what kind of lesbian magazines do you have? What kind of lesbian books do you have?”

Brooke: So you saw an opportunity in the market, you took it, and you ran with it. You basically drove the business yourself?

Franco: I did! But I had a great group of women I worked with. We all felt like we were doing this for the greater good, and we still feel like that. In the beginning, everyone was volunteer. We didn’t have an office. We didn’t have a computer. I mean, we started out with very limited capital and that was enough to physically print three editions of the magazine and nothing else.

Brooke: How did you get past that point?

Franco: An interesting question. We were starting to build up subscriptions, and it was about the second or third issue, and I was like “Ok, now is going to be the real test to see what happens.” I had a friend in the community, Barbara Grier, and she was the publisher of a lesbian book press called Naiad Press. I showed up at her office one day in my little business suit, at 21 years old, and told her that I’d driven three hours to meet her — I really wanted to meet her. She took me under her wing and said, “You know what, I want you to print out five thousand fliers. I’m gonna send them to my readers.” I told her I didn’t have $600 to print up the fliers. She said, “I don’t care what you have to hock, just get the money, and do it.” So I figured, “Well, what’s the worst case scenario? Five or six hundred dollars in the hole?” I got the money, and she sent out these fliers, with a personal endorsement, to her mailing list.

We used to have our “office” post office box in the copy center. So I’d go get my mail, and every day there would be something in the mailbox, and I’d be like, “Oh cool, a subscription.” A couple days there were like 5 subscriptions. So when the mailing went out one day, I went to the mailbox and there were 10 subscriptions, and I said, “Oh my gosh this is cool.” The next day I went in, there were like, 12, which was awesome, but I knew it wouldn’t fund the magazine. The next day I went in, opened the box — empty. As I’m walking out with my head down, the guy behind the counter said, “Your mail’s here, but we had to put it in a bucket because it couldn’t fit in your box.”

Brooke: Did you just know then?

Franco: I was like, “This is gonna work. Yeah, this is gonna be something.” Seeing the first issue of the magazine — actually opening the box and holding it in my hand — that was an incredible moment. And it really was one of the highlights of my life.

Brooke: How is the growth of the Internet affecting your business?

Franco: Some publications are like, “Oh no, what are we going to do? The devastation of print! Ahhh!” But we’ve looked at it as a way to extend our brand to lesbians who can’t get into a Barnes & Noble or a lesbian-owned bookstore. We’ve had a website since ’99, but last year we relaunched and now it has a lot more content. We also launched our digital edition, so people all over the world can buy a digital copy of Curve and read it online. It even makes little flipping noises when you turn the pages. And it has a lot of built-in, what I call “treats,” so when you go over a page, there are things you can scroll over and then link right to that site. There are embedded videos so instead of just reading about that musician, you can actually hear sound clips or watch a video of them performing. So the Internet has really allowed us to expand what our brand has to offer

Brooke: If you had one piece of advice for a potential entrepreneur or businessperson, what would you tell them?

Franco: Don’t let anyone tell you you can’t do it. That’s my life motto. If I had listened to all the people who said, “No, you can’t do it,” or “No, it’s a dumb idea,” I never would have taken the leap of faith. And I’ve had that faith all along. If you have an idea that you know people want, you just have to believe in yourself and not take no for an answer.

Comments

Great interview, Brooke. Money’s tight these days and I decided not to renew my magazine subscriptions…except Curve. That one’s important to me.

Thank you!

And it’s awesome that you’re continuing to support quality LGBT media…especially given the current economic environment.

Missy,

Thank you so much! Your subscription really means A LOT to all of us at Curve!

I love Curve so much. My favorite feature, I think, is Lipstick and Dipstick.

I think lesbians are trendsetting and awesome, but we are also slower to come out then the MENZ. So, you know, the great trendsetting lesbians need to come out and come out now, while they are setting these mad trends. I think Rachel Maddow and Brandi Carlisle, and HELLO, Tegan and Sara, are right at the head of this, and I couldn’t be happier for that.

I agree. We have to identify in order to show that we exist. And if we don’t “exist”, we’ll never be seen as a viable demographic or see equality.

I’m a magazine whore and Curve is one of my favorites. I’m too poor for all these subscriptions but I jus tcan’t give up Curve.

Also: Brooke deserves a bussiness statue (no idea what this is though). Or they should put her photo on the monopoly- money bills and they should call it Brookopoly then.

Obvs I’m in class because otherwise I won’t be typing down these nonesense.

Hey Daphers,

Brookopoly sounds great to me! How do I get this going? Get back to class!

First you trademark the name Brookopoly. Then you put the idea and details of Brookopoly on paper. Then you sell Brookopoly™. Then you give 75% of the money you got for it to me.

I love magazines and read them all and read the history of all of them. I eat histories of magazines. I want to eat this interview. Usually though I read about magazines that don’t exist anymore, like Spy and Sassy. But this magazine still does exist, which gives me hope. She’s literally one of my heroes, obvi. Also the part about the credit cards eased my debt shame for the day.

For half of this interview I felt like I was talking to you.

This is an excellent interview. I’ve never read Curve but I really enjoyed reading its story just now. People like Franco have all of my respect, those that have a dream and then throw everything into making it a reality. It’s inspiring.

this is so inspiring, seriously! also, the indigo girls cover is so great!

I just recently came out and started really looking into lesbian literature and media…I will definitely be subscribing to Curve in the near future…and by near future I mean next paycheck haha.Gotta support the female entrepreneurs!

The best thing about publishing Curve is getting comments like these! It means everything to us that we make a difference in your lives. Please support Curve by subscribing today at Curvemag.com.

p.s. This thumbnail photo doesn’t look like me at all… or does it?

I remember it when it was Deneuve. Yeah, I’m that old.

I thinks it sucked ASS! Fucking Stupid idiots on here!

Julia -frances.roots@ntlworld.com

I just wanna say that you guys ROCK my world!